“All Cities Had Them” – Court Street Was Watertown’s Red Light District In The late 1800s, Early 1900s

Mr. Watertown, Alex T. Duffy, once brought up Watertown’s red light district in a letter to the editor of the Watertown Daily Times on June 18, 1993. The topic of the letter, “A Walk Through The Past Along River Street,” broached the topic once his description of River/Newell Street reached the Guilfoyle Ambulance quarters. “Farther to the right, where Bruce Wright’s ambulance business is, there used to be four houses, part of Watertown’s red light district. All cities had them,” he wrote.

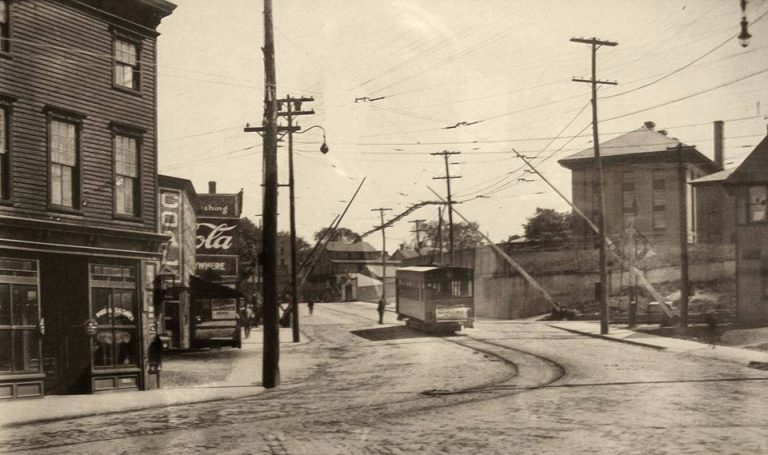

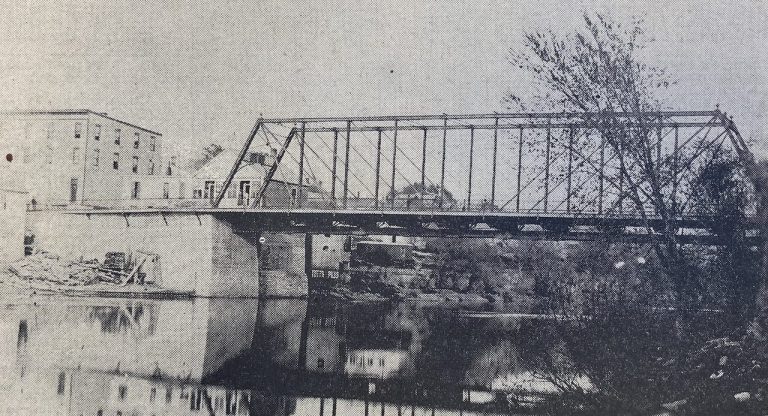

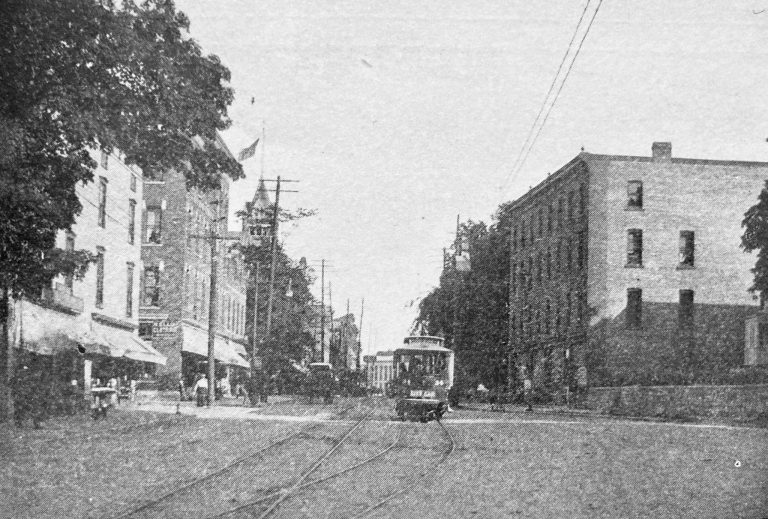

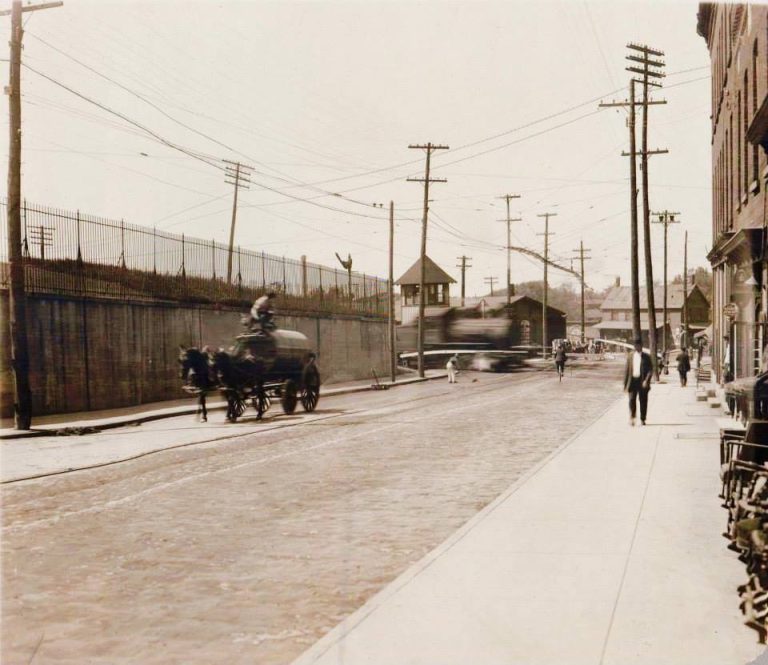

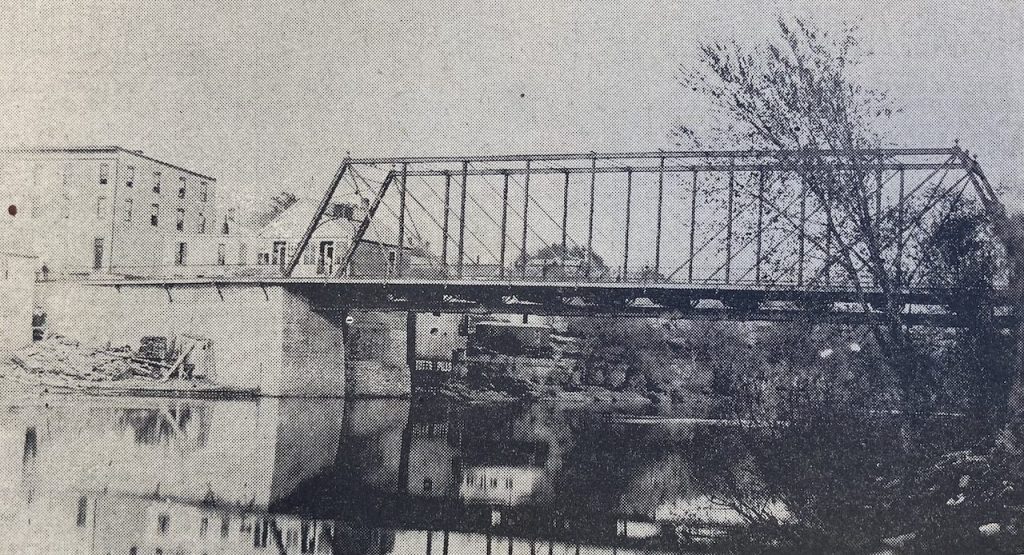

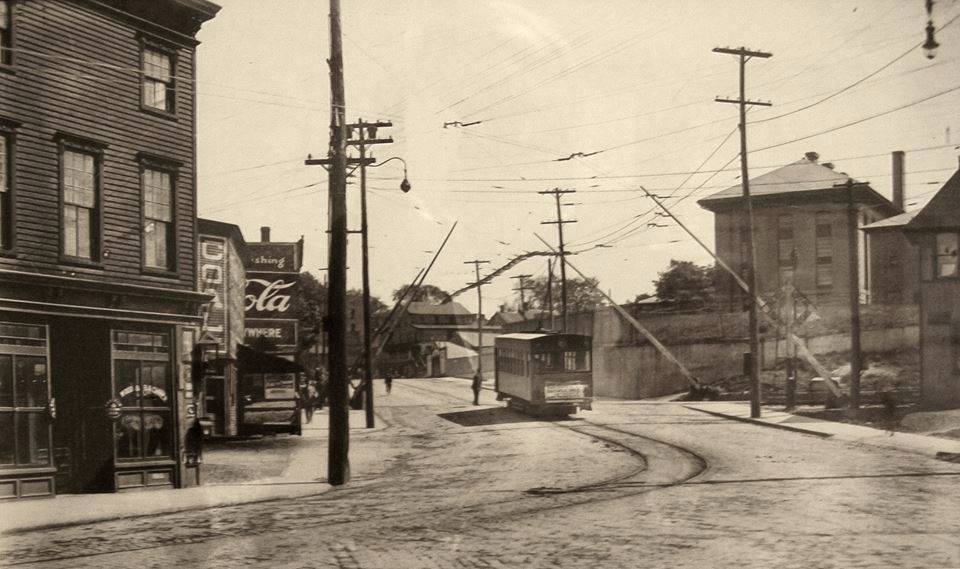

At that time, in the early 1900s, the Court Street bridge was made of iron and spanned the equivalent of the lower portion of the old, concrete double-deck bridge over the Black River. When veering to the bridge, Court Street itself went downward rather than up and over a span everyone is accustomed to.

A more detailed discussion of the area’s layout can be found in the article on the Court Street Bridges, but the configuration resulted in a busy intersection at Newell/River street that often got a little steamy, if not altogether seedy, once the sun went down.

The Court Street red light district began after passing the old city hall heading toward the bridge, and continued for a section into then River Street. Bars and cafes with unsavory names like Bucket of Blood, The Pig’s Ear, The Blue Light, and others like The Nugget of Gold were troubled spots, but crime, particularly prostitution and gambling, also occurred at any number of hotels in the area. The Oakland and Crowner Houses, The City Hotel, all reputable places, were not immune to the shenanigans after sundown.

An article published on August 26, 1899, in the Watertown Daily Times noted that police had been struggling with the problem for some time and that, between city hall and the Court Street bridge, 13 “drinking resorts” were to be found and that “many of these places draw loafers as a molasses barrel draws flies.” The article went on to note–

After nightfall many lower Court Street doorways are congregating places for boys and men who constitute, if not the worst element in the community, certainly the most conspicuously offensive. They assail the nostrils of passers-by with the fumes of vile tobacco and their ears with the viler profanity and obscenity. A lady cannot go up or down that portion of Court Street at night without hearing the language that disgusts even a man of any decency.

Chief Baxter, acting city chief, investigated the city’s uncodified ordinances and found the following “sweeping statute”–

Any person who shall make, aid, countenance or assist in making any riot, noise, false alarm, disturbance or improper diversion in the streets, in any public or private premises or elsewhere in the city; or who shall use any profane or indecent language; or who shall collect in any great bodies or crowds in any street or in any public square, to the annoyance or disturbance of citizens or travelers; or who shall unnecessarily assemble in crowds upon the streets or sidewalks so as to obstruct travel…

But wait! There’s more!

Or who, other than the owner, occupant or tenant, in any building, shall remain standing in or about any hallway or doorway opening into any street or in front of any store after notice to remove therefrom by a member of the police force or the proprietor or tenant or other authorized employee of such proprietor or tenant; or who shall remain lounging, loafing, laughing or idling on any of the streets, sidewalks or public places of the city, after notice to desist therefrom by any policeman, shall be subject to a penalty not exceeding $10 for each offense.

One particular place of offense was the Dewey House, which The Times wrote of on June 12, 1900, when a trial was underway at the county courthouse. Stenographers from the business college, presumably located at the Mohican building, were often sent there during practice trials, and, in this case, the proprietors, Florence E. and John B. Williams, were charged with keeping a disorderly house.

The Times reported–

For evidences of depravity, vice in all of its nastiness and unprintable testimony, this case comes very nearly being a prize winner. The evidence relates to the management of the Hotel Dewey before it became a concert hall.

Christopher S. Fox was the first witness and describe a visit to the Dewey house last October. He went into the room where the piano was and saw one woman in the corner, drunk. The lights were extinguished and one woman announced her ability to whip any man in the room in terms so forcible that no one could doubt what she thought of the ancestry of those present.

Hazel Kirke was the name given by the next witness, and in a bicycle skirt and sailor hat, she did not look over 14 or 15 years old. She stated, however, that her address had been River street for some time past, and at one point she boarded at the Dewey, her board being paid by a friend. Before she boarded there she had been a guest at the hotel at different times. She said she had been at other hotels, some of the larger ones in the city.

Chief-of-Police Charles G. Champlin testified regarding the reputation of the women who frequented the Dewey.

The jury deliberated for 15 minutes before coming back with a verdict of not guilty for John B. Williams and guilty for Florence E. Williams. The jury also asked for leniency for Mrs. Williams.

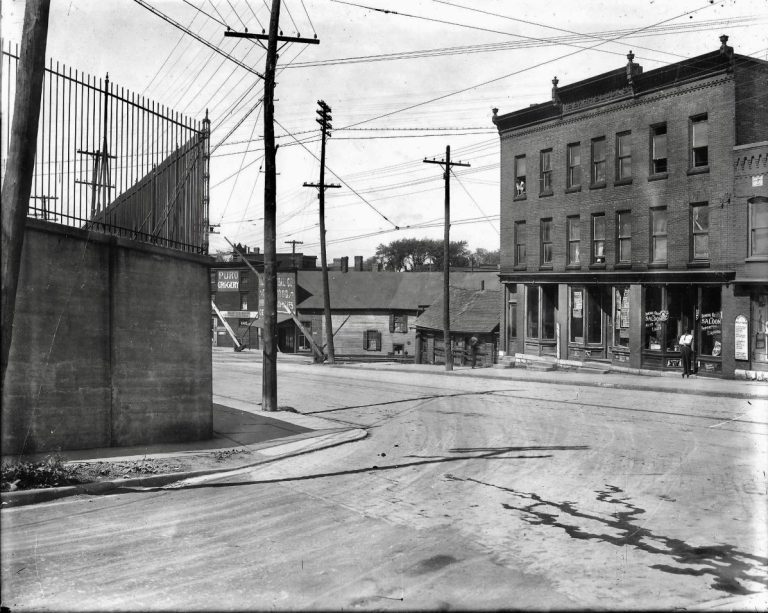

In 1901, residents of the city’s north side complained about the red light district. Obliged to pass by the notorious section just across from the Court Street bridge, they maintained the red light district was “disgraceful there and not fit for respectable people to pass through lower Court Street after nightfall.”

The city was short three policemen per its charter, requiring them to have one patrolman for every 1,600 residents. What made the red light district somewhat suspect, at least in terms of managing the degradation, was that it fell squarely between City Hall and the County Jail.

A letter to the editor in November of 1931, after businesses had replaced many of the saloons, made it clear that the city was turning a blind eye to the problem, fear-mongering its citizens with the notion that “licenses” contributed to the city’s coffers and that without them, it might not function properly. The letter’s description recalled the red district and situation, in part, with the following–

There was no provision of the law which the liquor dealers of this town, with the possibility one or two exceptions, made any pretense of observing. They sold after prohibited hours. They sold to drunkards. They sold beer to children to be carried away to their homes in pails. They maintained places on Court Street that were commonly known under the appropriate names of “Hell’s Kitchen,” and “Bucket of Blood.” Street brawls and staggering drunkards made this street unsafe for women to traverse after dark.

One such red light district street brawl was well-documented, to humorous effect, in the Watertown Daily Times on May 22, 1900, printed in its entirety below–

Women Fight Like Bruisers

A Battle of Fists Between Two Drunken Wretches

One of the strangest mills in all the written and unwritten history of the prize ring was “pulled off” about midnight last night in an alley off River Street. It was a brutal affair, and by comparison with it the Jeffries-Corbett fight or even a football game would be a refined amusement. The contestants were women, not “new” women, as the superficial reader might infer, but the type of woman that is as old as Lillith.

About midnight last night two women, Lizzie Lee and a woman named Mason, went into the saloon known in the tenderloin as “The Bucket of Blood.” Both women are inmates of places on River Street, and the Mason woman’s first name is said to be Pearl. She probably has as much right to this as her surname. The variety of whisky that is sold in these places is not the smooth, mellow life blood of sun-kissed grain, but a potent fiery potion with a fight in every drop, a bloody riot in each half-pint.

In a short time the women became pugnacious and wanted to fight in the saloon. The reputation of the place could not stand anything like that, and the bartender promptly vetoed this plan. Some one who did not want to see a good fight spoiled suggested that the women adjourn to the vacant space behind the block and there summit their differences to the arbitrament of fistic science. This suggestion was received with favor and the bartender who had prohibited the fight in the saloon consented to referee for the out-door affair.

The whole party went out to the rear of the block, and the women chose seconds, who stripped from them their outer garments and prepared them for the battle. The referee, watch in hand, called time, and the fight was on. The mill was fought under London prize ring rules with hitting in the breakaways, and lasted for six rounds.

Both women were severely punished, and blood flowed freely from the noses and mouths. Both fought so fiercely and so fast at the start that neither one had sufficient strength for a knock-out blow, and the fight would have been decided on points but for the fact that it broke up in a row between the seconds who separated their principals and indulged in a little fistic exercise themselves.

After this was concluded all the combatants retired to their homes to patch up their injuries.

So far as can be learned, the affair had not been reported to the police up to a late hour this afternoon.

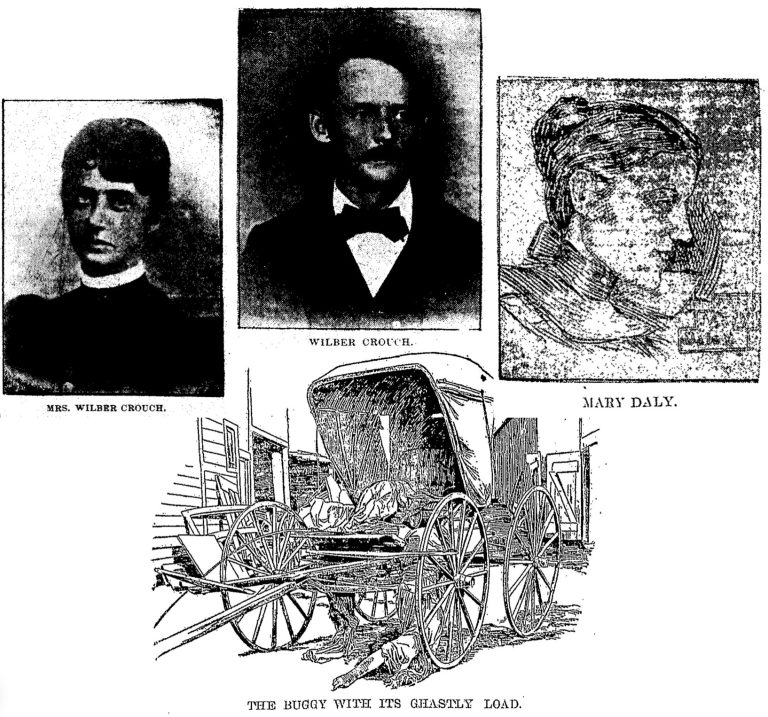

Another popular occurrence in the red light district was using some type of knockout drug in drinks. This led to at least one unsolved murder, an interesting case where long-forgotten pills were found in a well-known lawyer’s office decades after he had initially investigated the case.

In one particular incident described as “another unpleasant episode in the half-world last night,” that occurred in September of 1901 at the Bucket of Blood. Adolphus Lalonde came to this city from Canton to partake in its “extra circular” activities. Once again, The Times reported the incident with some creativity–

Yesterday Adolphus Lalonde of Canton came to this city and went to Anna Hazard’s place at 68 River Street. From that resort he took Anna Smith, a fragile fairy of about three hundred weight, and they went to Lee’s place. There were a number of persons there whose reputations differ in many essentials from that of the late lamented Mrs. Caesar.

The whiskey, also, is not above suspicion, and Lalonde had not had very many drinks of it before he hung himself up on chairback and went to sleep. When he awoke the dainty Anna was gone. So was $12 that Lalonde claimed he had in his pockets. It was learned that the Smith woman had called a back and left the place in company with Frank Nevills, a brother of the inglorious and thirsty “Pompey.”

Lalonde eventually made his way to police headquarters that evening and told his story. A patrolman was sent to Anna Hazard’s, and Anna Smith was arrested, later arraigned under the city’s charter for public morality and sentenced to either a $25 fine or 30 days in jail. She chose the latter.

In 1905, one unlucky visitor from Clayton came to town to have a good time and left minus one of his thumbs. After becoming violent and swearing up a storm in front of the Bucket of Blood at 7:30 p.m., Adam Weber was taken into custody by Officer Edghill, but not after “Weber swore big round oaths at the officer and attacked him,” biting his hand.

Edghill carried Weber to city hall and, after another struggle ensued, was able to get him in a cell with the help of another officer. Weber made to attack again right as the cell door slammed shut, catching his thumb in the latch. The Times reported, “the left thumb was caught in such a manner as to nearly sever it from the hand, the thumb hanging by only a bit of flesh.”

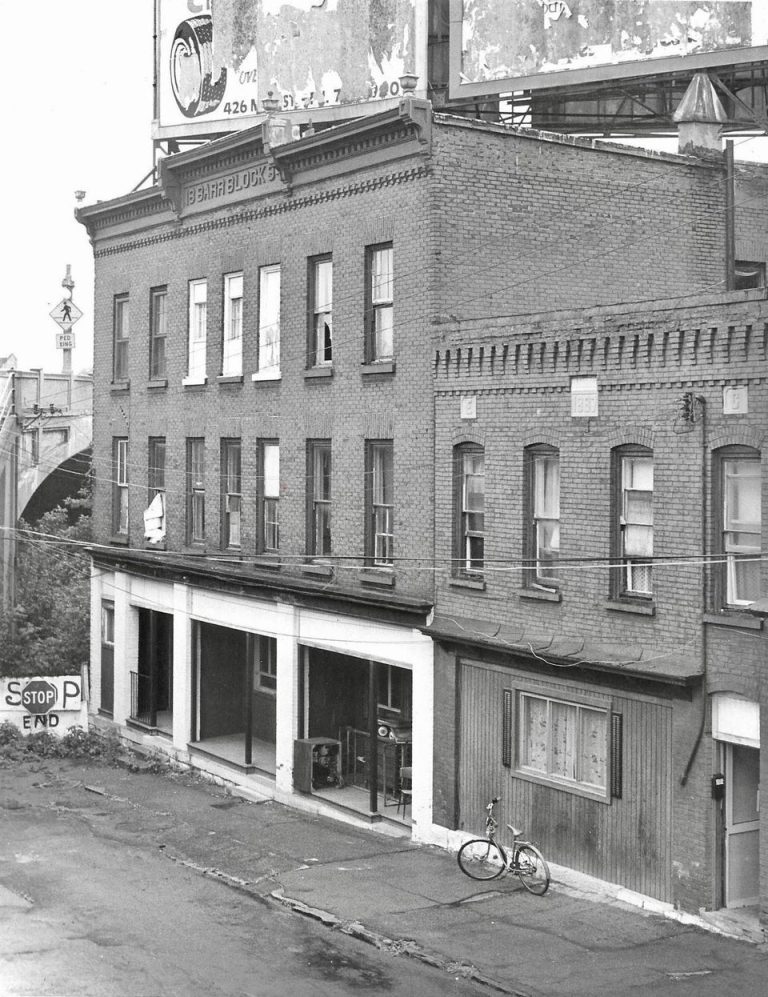

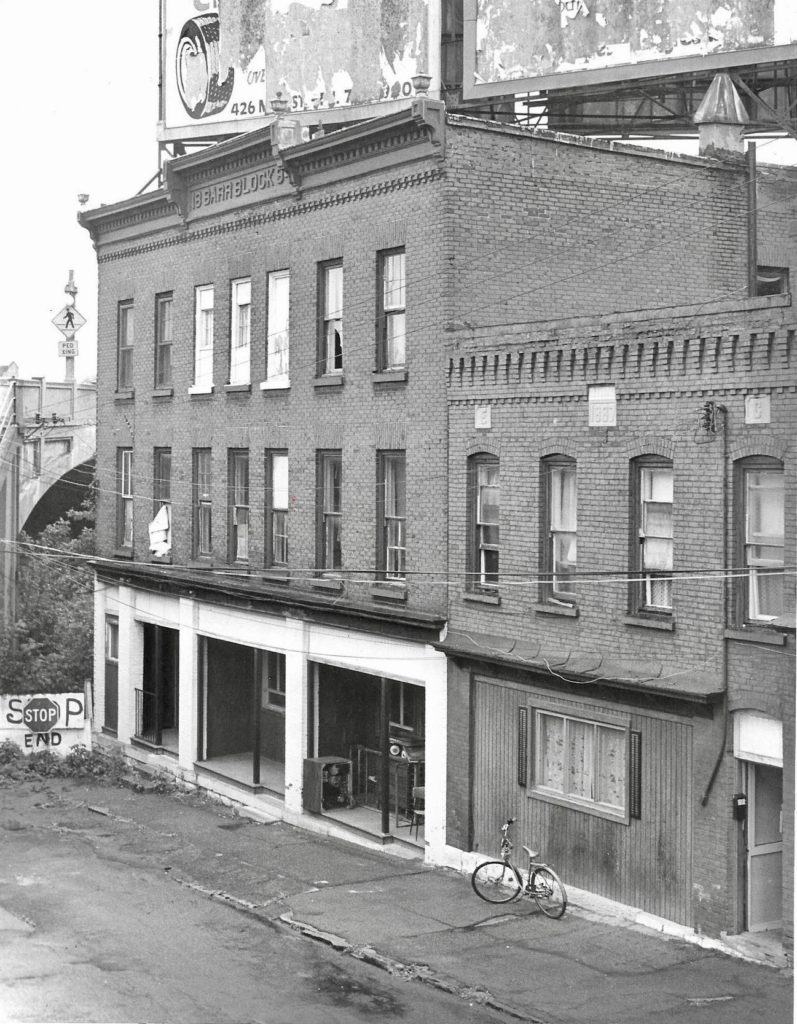

Even under new ownership and changing its name to The Nugget, or Golden Nugget, the cafe/saloon in the Baron Block couldn’t escape its past. The new owner tried valiantly to dismiss the place from being known as the Bucket of Blood, but couldn’t. The new Court Street bridge ultimately led to the area’s demise, which is an odd thing to say; perhaps maybe its salvation is more appropriate.

The Bucket of Blood, then known as the Globe Cafe, at least to its owner, had an auction along with the rest of the Baron Block, trying to salvage as much as possible in costs before the block, which was built in 1890 after a fire destroyed the previous structure, was gone for good compliments of the wrecking ball. The Times reported—

James B. Rush was the auctioneer and he amused the large crowd that had gathered at the place by his references to the place and recent reform campaign conducted by the ministers, pointing to the cafe as the “Bucket of Blood” and the “worst hell-hole in Watertown.”

As the previously mentioned letter to the editor dated November 20, 1931, stated, there was quite a difference over the next decade with saloons disappearing and legitimate businesses taking their spots. There’s little doubt that prohibition, which ran from 1920 – 1933, was the primary factor in cleaning up the red light district, with illegal activities now occurring “underground” and elsewhere in the form of bootlegging.

Today, Court Street is merely a shadow of its glory days; no, not the red light district era, rather, the center of commerce for the city of Watertown and efforts have been made to revitalize at least the upper portions of the street. All that remains of any watering holes on the street is the Hitchin’ Post Tavern, a mainstay since 1970.

At the end of Alex T. Duffy’s letter to the editor in 1993, he commented on watching the old double-deck bridge being torn down, and how he was the last one alive who worked on it in 1920. “Time marches on,” he said in closing. It sure does; whether or not some cities still have a red light district or not, people will still be painting the town red.