The Pullman Mansion on South Prairie Ave, Chicago, Illinois

Construction on the Pullman Mansion in South Chicago would begin in 1873 after George Pullman paid top dollar for the land on South Prairie Ave. The area, located just southeast of the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, would become the city’s epicenter for social and cultural high society.

For George Pullman, South Prairie Ave would be nearly 500 miles from his birthplace in Brocton, New York, a small hamlet between Buffalo and Erie, Pennsylvania, just off Lake Erie. The 42-year journey that would take George from small town Brocton to an estimated $400,000 – $500,000 mansion on South Prairie Ave would be due largely, and figuratively, to his invention of the Pullman car.

When George made his way to Chicago a year earlier, in 1857, he found similar work as he did in New York: moving existing structures for widening the Erie Canal with a device using jackscrews that his father had invented. Chicago was implementing an ambitious project to install the first comprehensive sewage system in the United States, and George’s expertise in raising and moving existing structures would serve him well. George’s mind, however, appeared to be preoccupied at times with an idea tied to the canal that kept afloat in his head ever since.

As written in A Souvenir of the Thousand Islands and St. Lawrence River, by John A. Haddock and published in 1895–

“During 1858 Mr. Pullman’s attention had been especially drawn to the long-distance sleeping-car idea. The sleeping accommodations afforded passengers were but enlarged copies of the bunk of the passenger packets of the Erie Canal – three tiers on each side of the car.

The following year, he began a series of preliminary experiments by remodeling two day-coaches on the Chicago and Alton road, and afterward did the same on the old Galena road. He was a pioneer, and met with little encouragement. The sleeping cars were invariably the property of the road they ran on, and their trips were limited to their own rails. No attention had been given to the idea of making long-distance railroading enjoyable. An entirely different conception of the future of American passenger transportation had now taken possession of Mr. Pullman.

Pullman would take a few years to work out his ideas, but the assassination of President Lincoln in 1865 would prove fortuitous for George’s “Pullman car,” as it would be called. Pullman would arrange to have President Lincoln’s body transported via a Presidential train car that Lincoln had previously commissioned from Pullman to travel from Washington, D.C., to Springfield, Illinois, with his family in another, separate Pullman car. The exposure results were overwhelmingly positive, and before long, Pullman had himself a business that manufacturing could hardly keep up with.

In the years preceding the construction of the Pullman Mansion, George would buy out competitors and, in 1871, team with Andrew Carnegie to bail the troubled Union Pacific and take positions on the board of directors. Having married Harriet “Hattie” Sanger in 1867 and having a couple of toddler daughters by then, Florence and Harriet, Pullman would hire architect Henry Jaffrey to build the Pullman Mansion. With no costs spared, it would be one of the most preeminent homes in all of Chicago once completed in 1877 (the family would move into the mansion a year prior, with the interior incomplete).

The three-story mansion would take up nearly an entire block with 7,000 square feet and feature a porte cochère. The interior included many large-scale rooms for entertaining, such as a 200-seat theater, billiards room, bowling alley, and a conservatory, amongst many others. Entertain is precisely what the Pullmans did, often having large crowds; some reported 400 attendees for events.

In 1880, Pullman hired Solon Spencer Beman to build not only a new factory south of Chicago but one of the early manufacturing towns to go with it, putting Pullman literally on the map. The town of Pullman, Illinois, would have many amenities such as shopping districts, parks, a library, and even a hotel, all without many of the vices that would be found in a city. It was as if George Pullman was creating an ideal place for employees to work, live, and play.

Unfortunately, the stars weren’t aligned with Pullman’s dream utopia as it slipped into something more akin to feudal serfdom. 12,000 people were subjected to Pullman’s every whim, so much so one employee, according to illinoislaborhistory.org, reportedly said: “We are born in a Pullman house, fed from the Pullman shops, taught in the Pullman school, catechized in the Pullman Church, and when we die we shall go to the Pullman Hell.”

Indeed, by 1893, at the onset of a depression, “Pullman Hell” became a reality as George cut wages 30% and required longer hours from workers while maintaining their same rent payments – all to keep his personal interests profitable. One source reported, “A workman might make $9.07 in a fortnight, and the rent of $9 would be taken directly out of his paycheck, leaving him with just 7 cents to feed his family.”

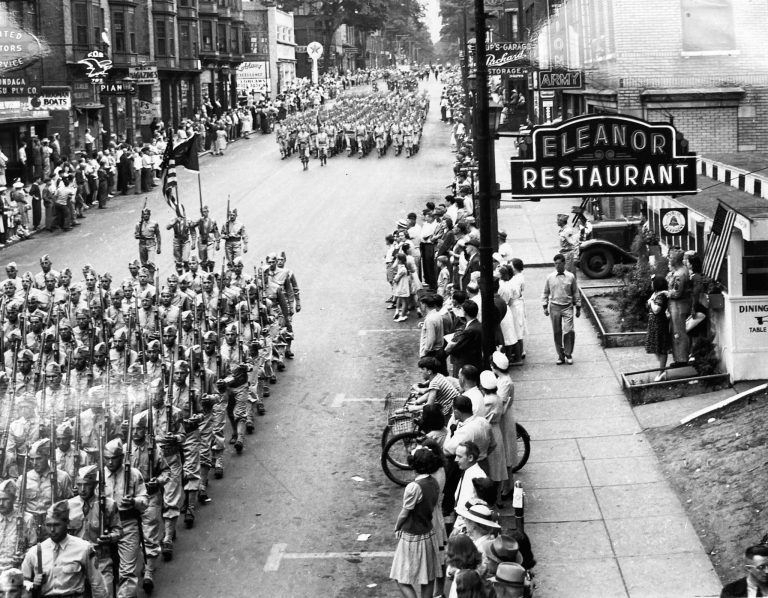

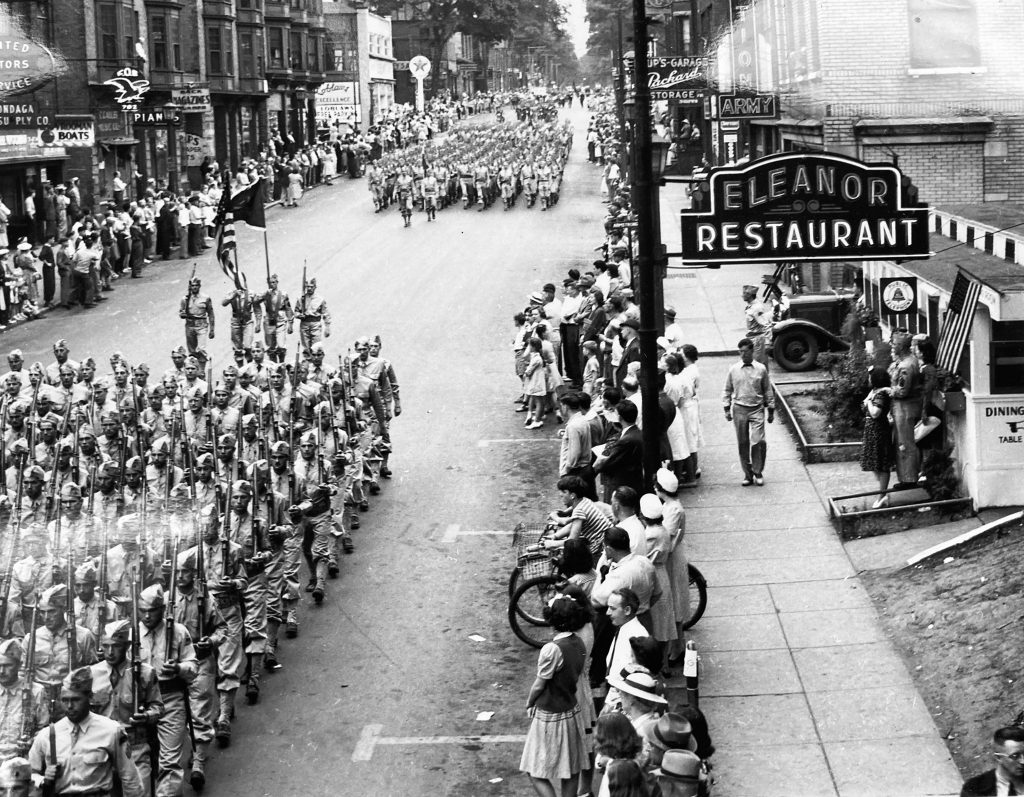

The result was the infamous Pullman Strike that involved the American Railway Union (ARU) against the Pullman factory in Chicago in the spring of ’94. 4,000 workers in Pullman, Illinois, went on strike after decreased wages. When it failed, the ARU launched a nationwide railroad strike against trains that carried the Pullman car.

Rather than deal with the strike and calls for arbitration, Pullman would retreat to his Thousand Islands summer residence, Castle Rest, which he had built six years prior for his mother. One of the earliest occupants of the islands, having purchased it in the mid-1860s, Pullman would later put the area in the national spotlight when inviting President Ulysses S. Grant for a weeklong retreat to his then wooden cottage in 1872.

With nearly 250,000 workers on strike and riots breaking out, with a reported 30 people killed in Chicago alone and nearly $80,000,000 in damages, President Cleveland ordered the U.S. Army to keep strikers from interfering with the trains after an injunction against the union was ignored. Later that year, President Cleveland and Congress would mark Labor Day as an official holiday in a move that was seen as conciliatory to organized labor, and the Pullman strike ultimately marked a turning point in its movement.

Perhaps the stress of becoming one of the most hated men alive did George Pullman in. He would suffer a massive heart attack and pass away at the age of 66 in 1897. Fearful that former employees and their supporters may desecrate his body, the family had his body placed in a lead-lined mahogany coffin that was encased in concrete and buried beneath even more concrete in a process that was said to have taken two days to complete the funeral.

His widow, Harriet, would continue living in the Pullman Mansion and making at least one trip to Castle Rest a year but considered their summer home in Elberon, New Jersey, “Fairlawn,” her favorite. Having first visited the area in 1871 while guests of President and First Lady Grant, the Pullmans would again employ Henry S. Jaffray as architect to design their summer home. After George’s death, Mrs. Pullman would have the mansion completely redesigned by Solon Spencer Beman.

After the marriage of eldest daughter Florence to Frank O. Lowden, who had high political aspirations (he would fail to capture the Republican nomination for president twice), Mrs. Pullman would have another mansion built in Washington, D.C., in 1910. Frank would serve as U.S. Representative from Illinois from 1906 to 1911, necessitating the family live in Washington, D.C., but would decline to run for another term, and the mansion was subsequently sold with hardly any use at all (it would sell again, just months later and become the Russian Embassy for many years.)

Lowden would go on to become Governor of Illinois before his unsuccessful attempts at the Presidency, turning down a nomination for Vice President in between his failed bids.

Mrs. Pullman would continue to live in the Pullman Mansion and hold social events, but the times were changing. One could conceivably say, from the late 1890s until she died in 1921, was the “There goes the neighborhood” era as the industry started moving closer and closer, displaced as downtown Chicago grew. Areas around South Prairie Avenue would become home to warehouses and industry, even more so after the automobile allowed people to live further away from their workplace, which steadily crept to the Pullman Mansion’s backyard, causing a maximum exodus of residents.

After Mrs. Pullman died in 1921, daughters Florence and Harriet held a massive three-day auction at the Pullman Mansion. Anything and everything was for sale, as the sisters, married to successful and notable men and living in areas outside Illinois, decided to have the mansion demolished afterward. The auction brought out the public in mass, who had their first chance to step inside the Pullman Mansion and see what they could only imagine for years prior.

For those seeking an in-depth look at the Pullman Mansion, the excellent documentary The Pullman Mansion was completed last year and features an array of photos, a detailed overview of the floor plans room by room, and even a recorded oral history from the 1970s. The video is below, but you may want to view it directly on YouTube.