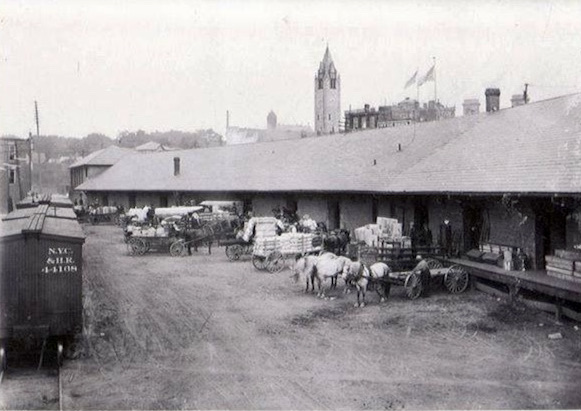

The New York Central Freight House Was A Game-Changer For Watertown, N.Y.

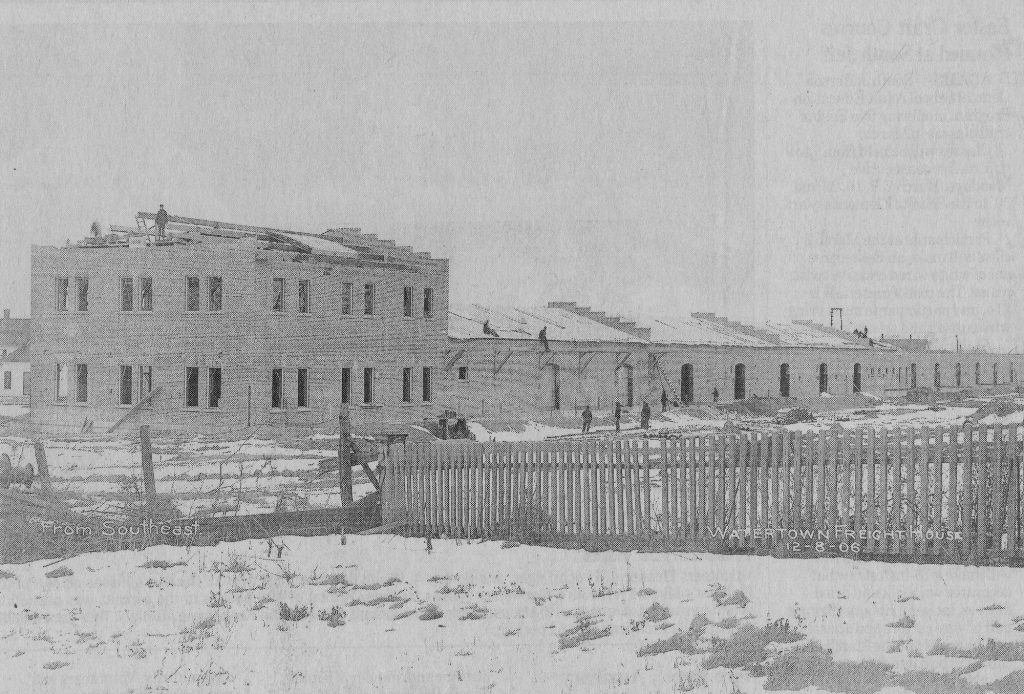

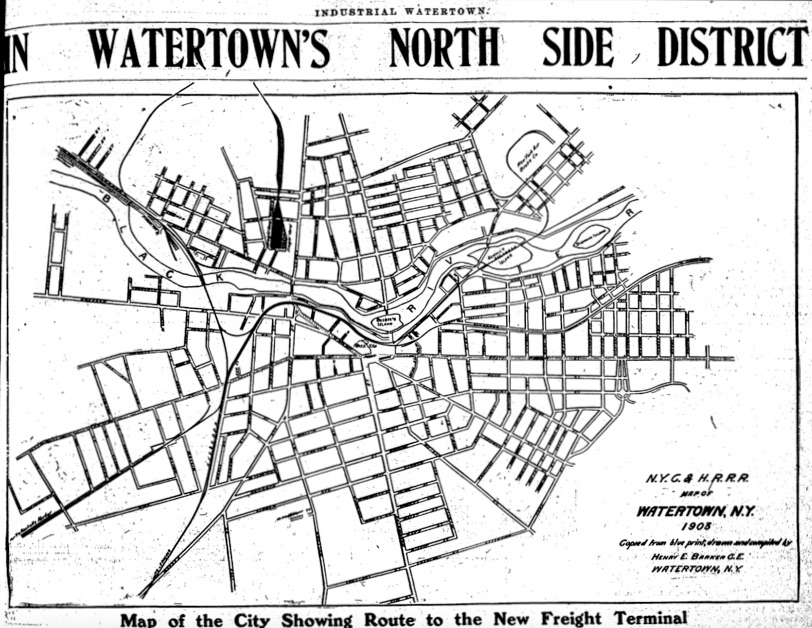

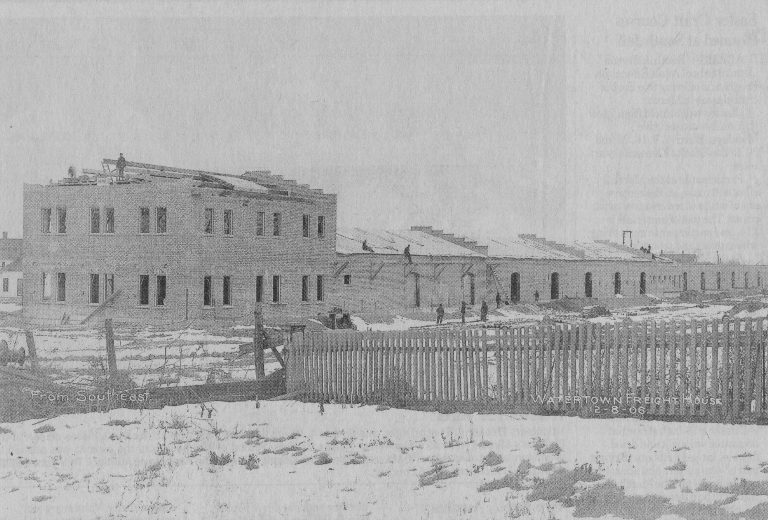

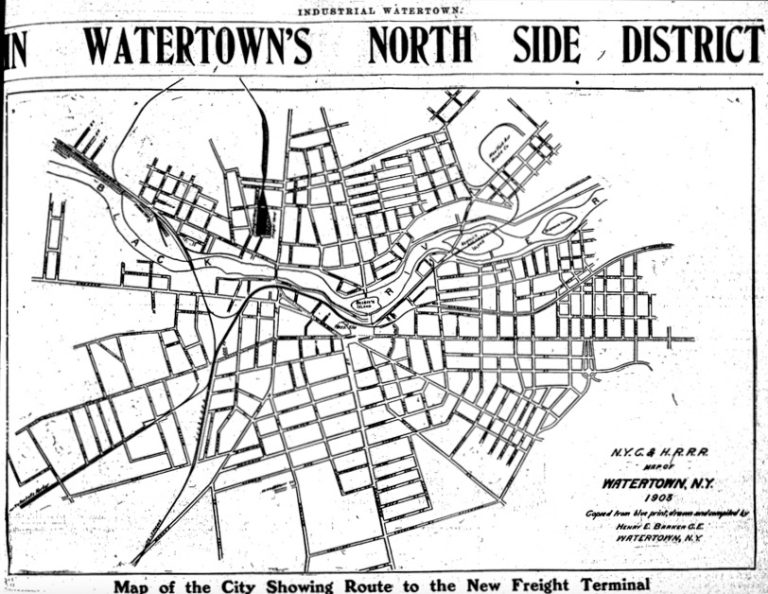

In late 1905, the New York Central Rail Road approached the city of Watertown’s Common Council, seeking to build a new freight house between LeRay and West Main Street. The implications of New York Central’s vision were a positive move toward further growth for the city and the Black River, providing a source for electric power still in its early years of development, made Watertown an attractive hub for manufacturing. However, the actual implementation of such an effort, particularly with regard to its location, brought about a number of issues.

One of the greatest concerns was the access to and from Main Street and the city’s insistence that any crossing there should be an elevated, overhead crossing or one below grade. Not only did the idea of trains passing through a major thoroughfare pose a stoppage of traffic concern, but also a general safety one as well.

The New York Central saw little opportunity for industrial expansion on the south side but found the north to have plentiful opportunities. In their eyes, Watertown as the city of the future was a short-term reach, not a slogan to be used sixty years down the road.

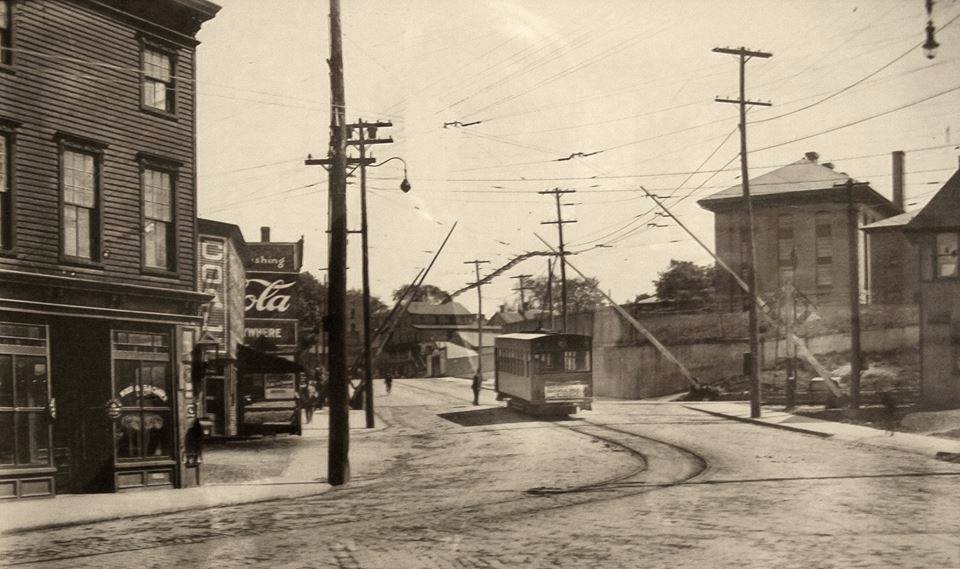

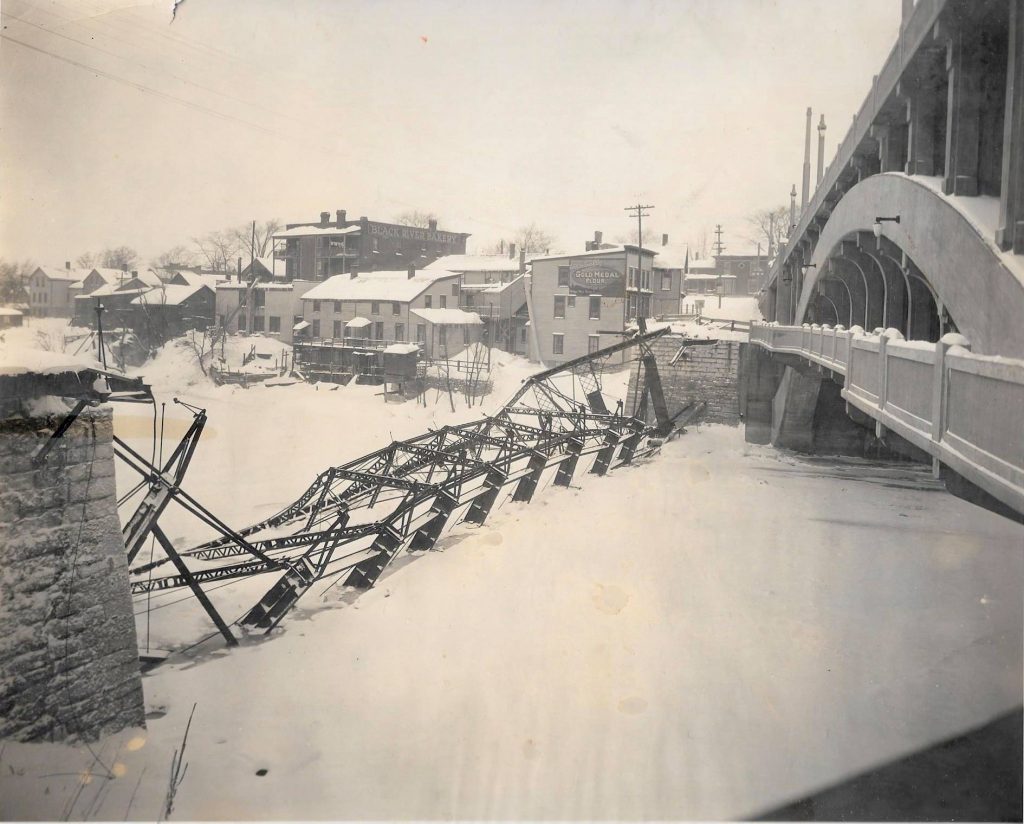

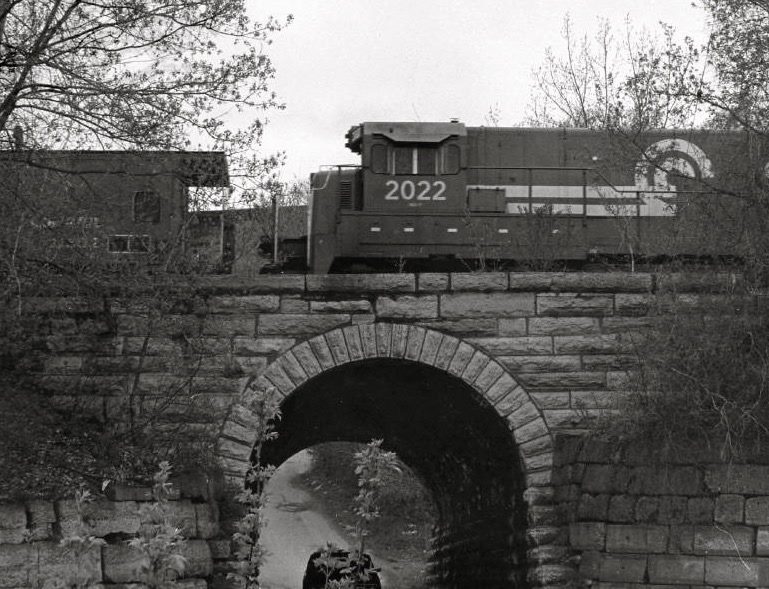

Both the city of Watertown and New York Central were eager to do away with graded crossings that plagued Court and River Streets and would result in a number of fatalities in the coming years at the Massey Street Crossing – but the question remained, how to go about doing it?

The following series of three photos exemplify the numerous hazards found at the Court and River Street junction:

During a follow-up meeting a few weeks later, the committee presented majority and minority reports, removing a requirement for a new bridge though no definitive action was taken. The Watertown Daily Times would report in their January 17th, 1906 edition–

Judge Purcell was present at the meeting last night, representing the railroad company, and assured the aldermen in emphatic terms that unless the city altered its position in demanding of the railroad company a payment of one half of the costs of the construction of a new bridge across Black River, the matter of the new freight yards would be permitted to go down.

The bridge, a wish-list item for some 20 years that was considered to have been built at Jackson Street, was officially stricken from the requirements a week later and assured the new freight house project of moving forward provided the New York Central agreed to the following clauses:

- The rail-road company eliminate the Main Street grade crossing where the street is crossed by the Cape Vincent branch, and suggested that as a means of elimination the tracks be elevated.

- A satisfactory entrance to the freight yard, leading from Main Street near the Goodale property, or the Bethany M. E. Church property.

- Third and fourth considerations were placing in repair by the railroad company all sewers, manholes, grades, etc. which may be altered or rendered in a state of misuse by reason of the proposed construction work.

- Provisions be made for a new sewer in the north part of city where the route as proposed crosses the railroad between LeRay and Bradley Streets in the vicinity of Cowan’s (Kelsey) Creek and also upon Central Avenue.

- A general liability clause, transferring to the railroad company and asking for an assumption by the company of all liability in litigation that might result by reason of the proposed construction work.

- The railroad company extend Burdick Street through to Bradley Street, at its own expense.

- The railroad purchase property between LeRay and Morrison Streets on Binsse Street and also the property on the westerly side of Flint Avenue.

- Provide the grade for the tracks crossing Bradley, Snell, Burdick and Binsse Streets, be at such a grade as the city engineering may establish.

- In the event of the elimination of the Court Street grade crossing, a proper overhead crossing shall be constructed over said tracks or grade crossing on Court Street for the accommodations of pedestrians only. This clause, in general interpretation, called upon the railroad to pay half the cost of construction of a new bridge and overhead crossing.

- The eleventh clause was later altered to give the railroad “reasonable time” in which to complete the work.

- The twelfth and final clause stated the permission or license shall become null and void if the railroad failed to perform any and all of the conditions and obligations of the conditions and agreements listed above.

The significance of this cannot be understated. Foremost, in 1907, the Court Street Bridge was iron and already 23 years old. The situation it posed, after the new freight house was constructed on the North Side, is best demonstrated with the following letter to the editor of the Watertown Daily Times printed on April 11, 1908—

One day this week, I noticed a broken lumber wagon in the street a few feet from the north entrance of the Court Street bridge. Several heavy loaded trucks, besides lighter vehicles, sandwiched in near a street car made things interesting for awhile. The car was already stopped and teh drivers of the heavily loaded wagons managed to get their property through without further accidents aside from the delay.

This is only one incident, I am informed, which is of daily occurrence in this locality. The great amount of freight carried to and from the freight house is the cause of present congested condition of this thoroughfare. There was sufficient traffic over this street and bridge before the removal of the New York Central freight house. The conditions existing in this locality today cannot be realized unless you have had occasion to frequent this thoroughfare.

Had Watertown not managed to get the New York Central to contribute to the Court Street Bridge effort, the city would have been liable for the complete costs. It was known that the new freight house would cause substantial traffic over existing bridges, and to build a new one that “as ought to be built would not cost less than $200,000.” At the time, the city was within $120,000 of its bonded indebtedness.

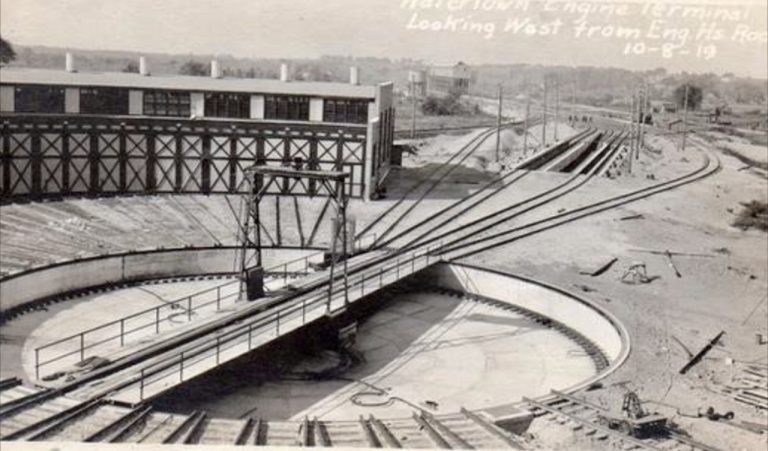

Adding to this, in one of the earlier meetings, but not part of the clauses, R. J. Buck, the city’s postmaster, wanted to go on record as being in favor of a new passenger station, saying the council should keep in mind the “crying need” of the city for a new passenger terminal. A portion of the old freight yards were already at that location and planned to be demolished once the new freight house off of Main Street was completed.

Why not take the opportunity to give the burgeoning city a modern terminal more fitting of its status?

In March of 1907, New York Central promised a new passenger terminal to replace its old depot after the new freight house was completed. There would be many delays, but the new passenger terminal would finally open on June 15, 1911. This was a major win for the city, which now would have one of, if not the finest, passenger terminal on par with cities such as Rochester and Buffalo.

As for the Court Street Bridge, it too would face a number of delays. Studies would need to be performed, designs submitted and selected, contracts drawn and awarded, etc., a good majority slowed by the needs of World War I. Having selected a design that deviated from the current iron bridge’s path, allowing for the new bridge to be built without needing to remove it, provided many benefits – but would present its own obstacles in the process.

The city would need to acquire a portion of the County’s Jail’s property and the retaining wall for the construction of the new bridge, as well as a number of structures on both sides of the river. One of these, The Baron Block on the corner of Court and River Streets, was a godsend for local and state authorities who had long-battled with one of its most notorious watering holes, a saloon better known as “Bucket of Blood” in Watertown’s red light district.

All of these would take time to resolve before construction could even start. When it was all said and done, the bridge would open September 28, 1921, with the city of Watertown paying one-quarter of the costs of construction, the State of New York another quarter, and the New York Central Rail Road fifty percent.

The bridge, a double-decker steel, and concrete bridge, would be one of a kind, meeting all the requirements set forth years earlier, allowing pedestrian, trolley, and motor traffic to cross overhead while a lower level deck would allow for direct traffic to River Street. Traffic for automobiles could drive on River Street under the bridge, and so could trains, all doing so without any convergence of lines that would result in accidents.

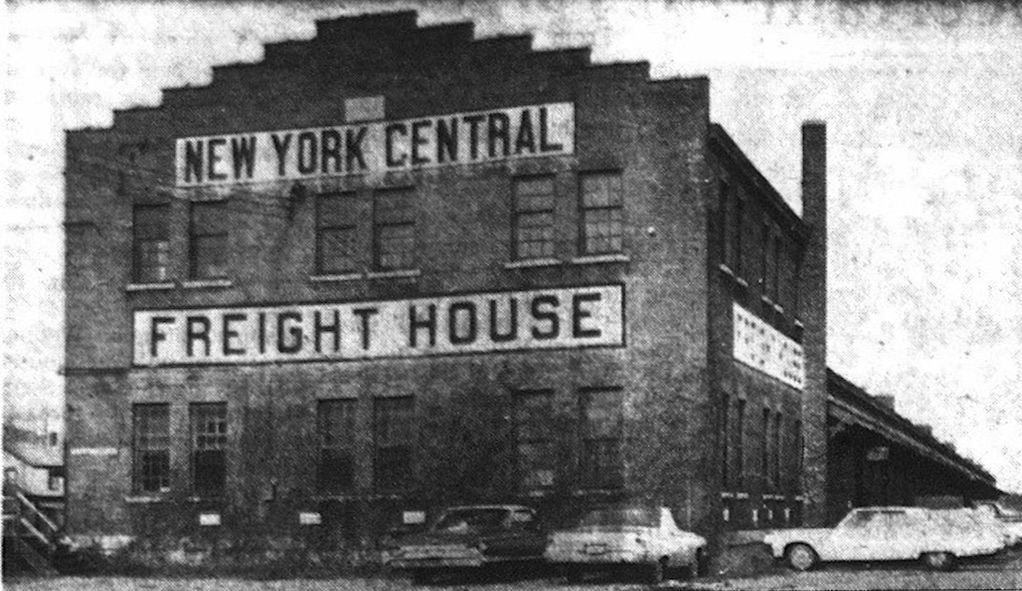

In 1966, the New York Central would merge with Pennsylvania, becoming Penn-Central. In 1973, Penn-Central sold the old freight house for an estimated $100,000 to Edmund Street Realty which would renovate and convert the structure into a retail and wholesale building materials center known as Watertown Home Center. The business would last only three years in the location before exiting.

Today, the old freight house appears to be a building from that time, and just about everything else has been forgotten. Nestled off W. Main Street and almost out of view, its unassuming presence conveys not an ounce of hustle and bustle of the activity that once occurred there, yet it’s hard to fathom the old freight house is still standing while the two major pieces of Watertown’s history that were born from its construction, the double-decker Court Street bridge and the Watertown train station, are both long gone.

2 Reviews on “New York Central Freight House – Est. 1907”

I’m pretty certain that this Memory Lane has been rewritten or reformatted from the original. TWO captions are now incorrect:

The photo on the right was just added. The caption came from the Watertown Daily Times. The RW&O Railroad was a subsidiary of NYCRR, until it was formally and didn’t formally merge until 1913 as far as I recall reading; I didn’t write the caption and I can’t speak for The Times, but that would be my guess.As for the caption being incorrect: that’s the TITLE of the article, and it’s on every single photo, just the same as the vast majority of other articles. I didn’t have them added in originally but did so when I updated the article last night.

Right at the front of the freight house are the only known existing cobblestones in the city.

I’ve actually never been down there. I’ll have to stop by there sometime when I’m in town again. It LOOKS like stepping back in time, though.