Henry Barr, A Former Slave From Kentucky, Builds Barr Block On Court Street In 1895

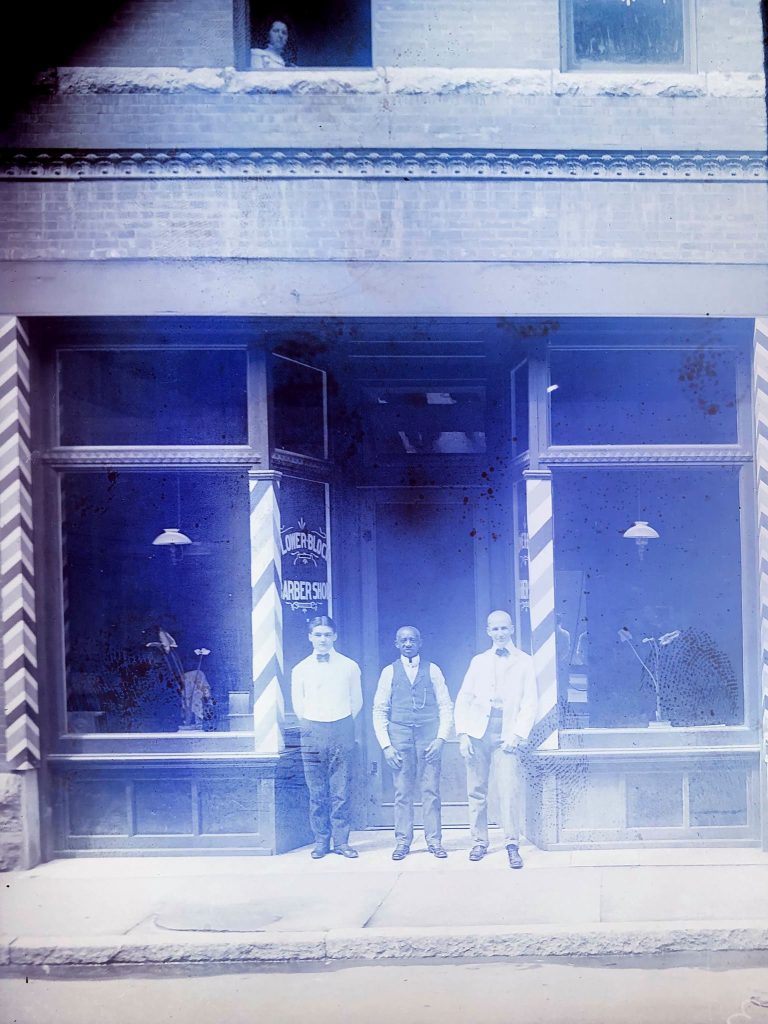

The Barr Block was erected by “Professor” Henry Barr, an uneducated former slave who, after becoming a free man, migrated north to Montreal but soon came to Watertown, a growing city at the time. Here, he opened tonsorial parlors in the Woodruff Hotel and, for years, ran the finest equipped barbershop in the city.

As a successful businessman and leader in the African American community, Barr was one of the first members of the Thomas Memorial AME Zion Church’s Board of Trustees. The Henry Barr Underground Railroad Community Development, Inc., was named in his honor.

Each of Watertown’s hotels had a barbershop for the convenience of out-of-town travelers; many of those shops were operated by African Americans, all of them trained by Professor Barr. Barr’s accumulated savings gave him great power within Watertown’s African-American community. He could make loans to assist other barbers in establishing shops; he bought and sold real estate, owned rental properties, and supported his church.

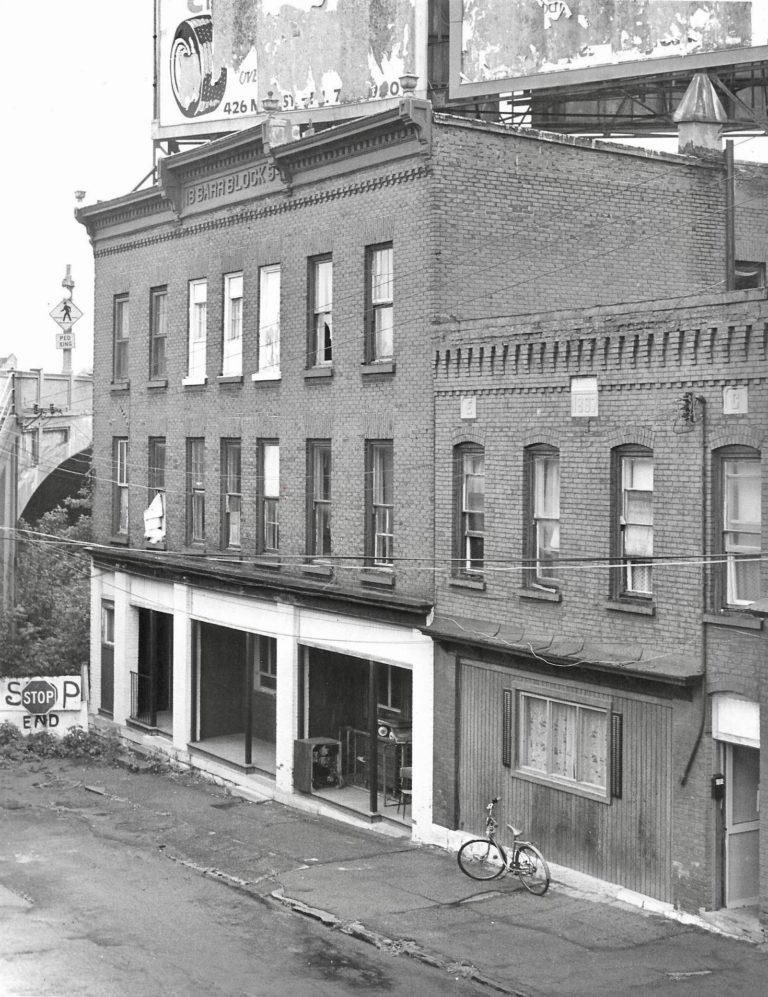

It was in later years, 1895 to be exact, that Barr found himself erecting the eponymous Barr Block, the first commercial building in Watertown, N.Y., to be built by an African-American, where he continued his barbershop for a number of years before passing away in 1902 under dubious circumstances. From Larry Corbett, who contributed to a posting on Facebook’s You Haven’t Lived In Watertown, N.Y. If– page, information regarding Barr’s death:

On Saturday, February 8, 1902, Henry Barr was in his apartment on the second floor of the Barr Block when he heard a commotion in the stairway and went to investigate. An extremely intoxicated man, an ex-convict named William Sully was coming up the stairs, looking for an ex-girlfriend who was living on the third floor. He had previously threatened to do her harm and she had asked ‘Prof’ Barr not to allow Sully into the building.

The 67 year-old Barr stood on the second floor landing and refused to allow Sully to go any further, ordering him out of the building, at which point Sully may or may not have struck the old man (there were apparently no witnesses.) Barr went back into his apartment and sent his son Eddie for a policeman, then collapsed.

A doctor was called and the unconcious Barr was taken to St Joachim’s Hospital. Sully was arrested and taken to the lockup in City Hall, where he experienced alcohol withdrawal and delirium tremens for several days.

Barr died about one week later and an autopsy was performed on his body. Finding no bruising, but evidence of a stroke, the coroner ruled that Mr. Barr had died of natural causes and Sully was released, the judge admonishing him not to celebrate his freedom by getting drunk.

Many residents felt the ruling was unjust; that Sully had gotten away with the murder of a beloved member of the community.

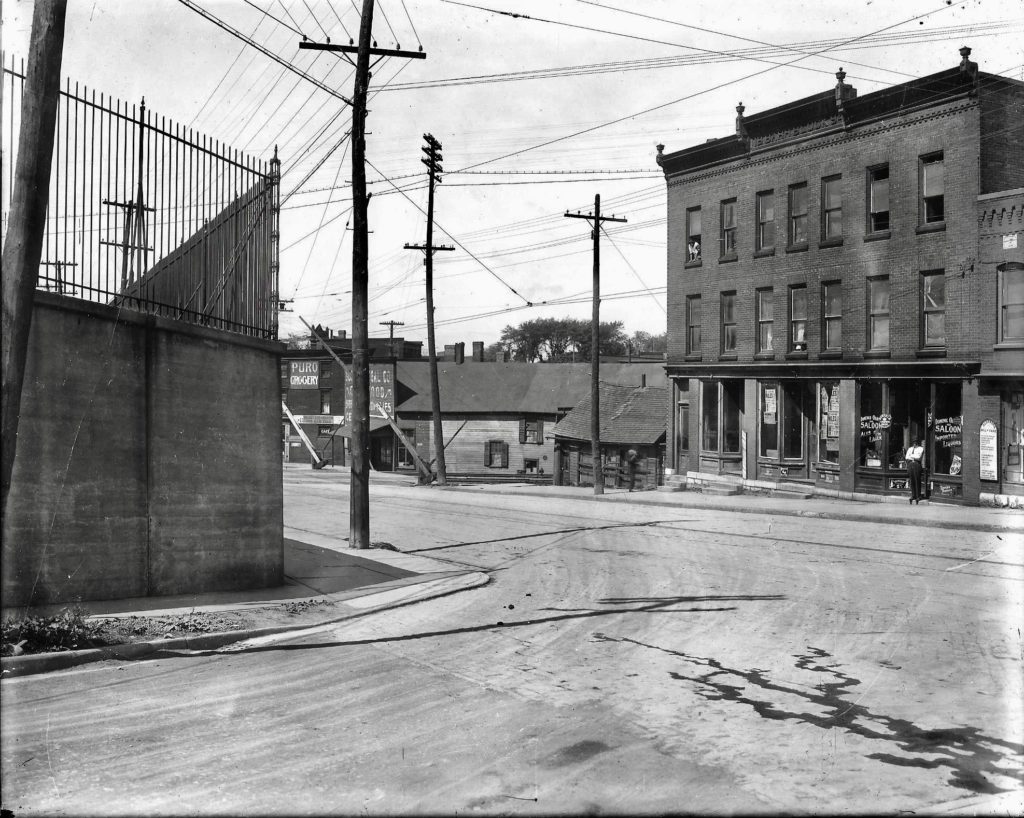

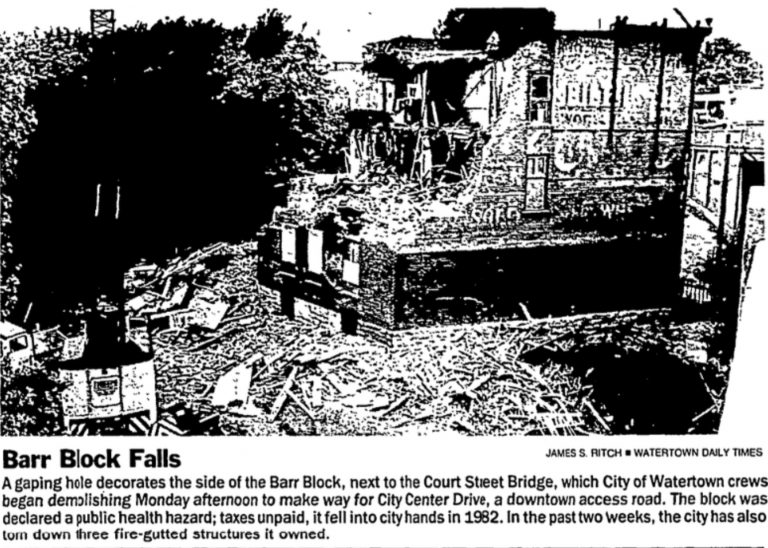

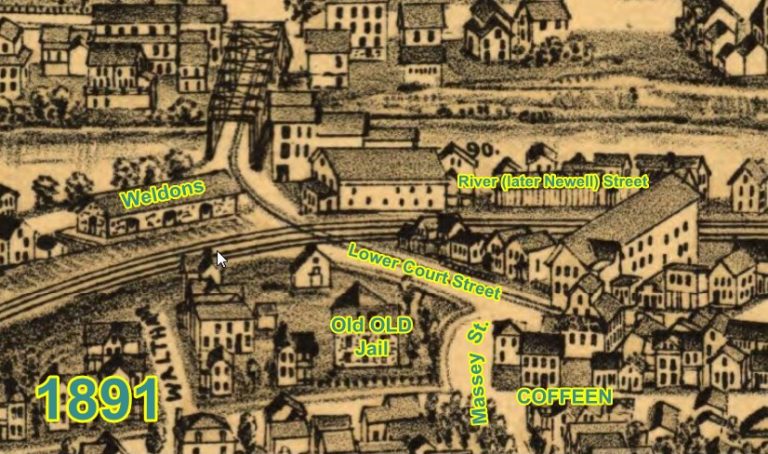

The Barr Block, once part of the lower Court Street businesses that lead to River (Newell) Street and the Old Court Street Iron Bridge, would, in later years, find itself at the end of the road – literally and figuratively.

In 1982, the block would fall into the hands of the City after a failure to pay taxes. The building would sit vacant and eventually be condemned and considered a health and safety hazard in 1984. It would take another three years, but on May 18, 1987, the Barr Block would be razed by city workers.

1 Review on “Barr Block 468 Court St (1895 – 1987)”

This Memory Lane about the Barr Block is the perfect one to better explain the whole saga of the former North Court Street area, also known as Lower Court Street . While Lower Court Street became the city’s area of ill repute–many railroad men and out-of-towners visited “ladies of the evening” in hotel rooms and apartments–a look at Polk’s City Directory books (directories back to the 1890s are available at Flower Library’s Reference section), list dozens of apartments, grocery, meat and fruit stores, bars, diners, coal and lumber dealers and several offices, a busy, slightly industrial area on the streetcar track connecting it to downtown and the rest of the city.

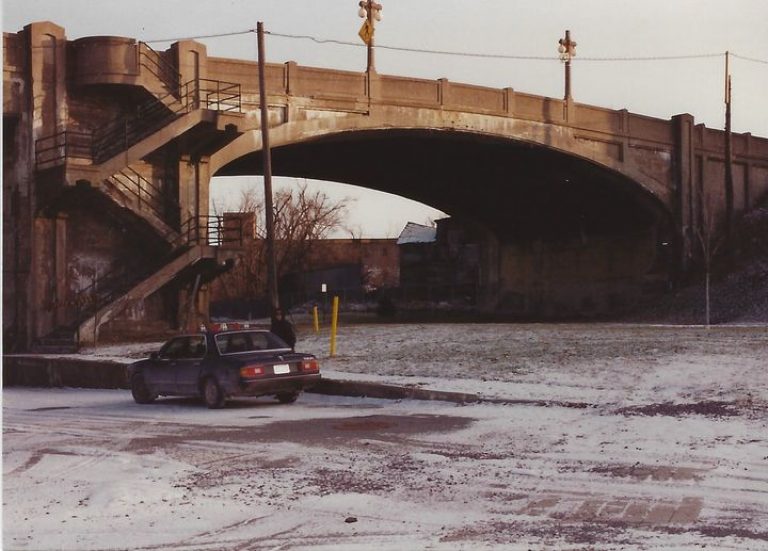

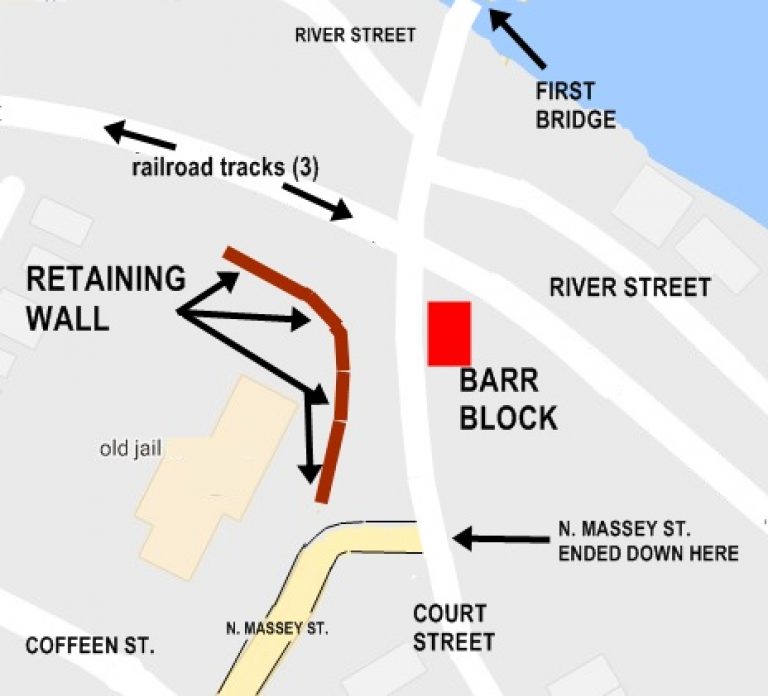

As the New York Central RR (NYCRR), freight house deal came together (please see the Memory Lane story about the Freighthouse), a major issue was the building of the magnificent double-decked concrete Court Street Bridge to ensure a way for more and heavier traffic and streetcars to cross the Black River, River (later renamed to Newell), Street and the three NYCRR tracks. Begun in 1921, the astounding structure used three different types of arches and the newest concrete construction techniques to span ALL THREE obstacles, plus connecting LeRay Street directly to North Massey and Coffeen streets while still allowing access to the ground-level streets below.

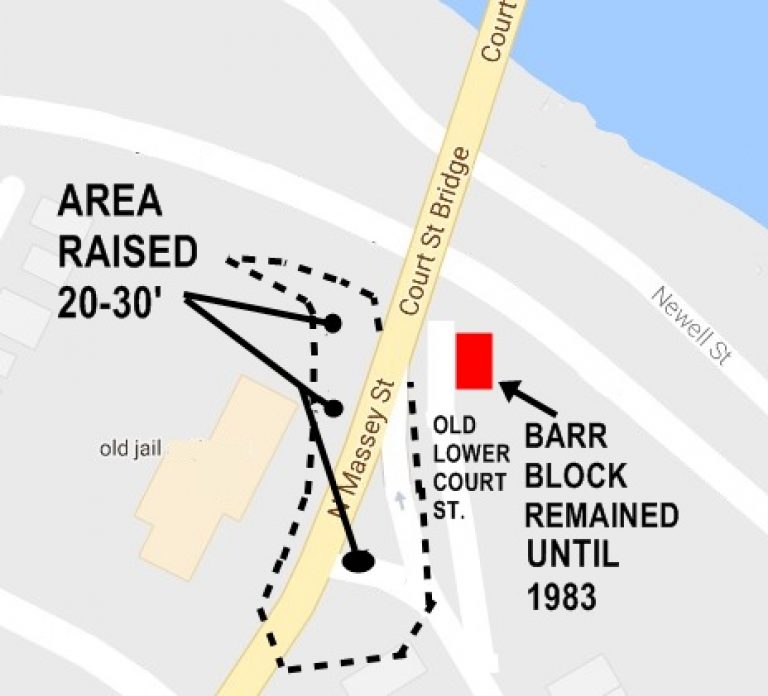

The unfortunate casualty of the new bridge’s location was the obliteration of the vibrant North Court Street community. All of the buildings except the Barr Block and the Weldon coal, lumber and feed store were ripped out as the bridge construction gathered steam after years of waiting. While the Edmund Street Freighhouse opened in 1906, it took 14 more years to hammer out the huge and complex financing package shared by the city, New York State and NYCRR, and of selecting engineering and design companies from New York City and Germany and the main construction contractor from Buffalo.

It’s hard to imagine the difference to area residents crossing between the north and south parts of Watertown via the new structure. As shown in the before-and-after maps (see images), the area just east and north of the Jefferson County Jail was raised by 30 feet to give the 40-foot-wide bridge a place to land while totally eliminating the dangerous railroad crossing and busy commercial traffic below.

Interestingly, the bridge’s southern end was in the northwest corner of an area of land called Madison Square, assembled by visionary Watertown pioneer Henry Coffeen a century before as a prospective business area to compete with the busy Public Square ( https://tinyurl.com/yyn2rzc7 ). A discouraged and debt-heavy Coffeen left Watertown for Illinois ( https://tinyurl.com/mxdue9xa ) because Madison Square never became the busy business hub that he had hoped for, but fate and a new freighthouse for the railroad–all but unheard of in 1815–would prove the city’s first real estate developer right after all, it just took 109 more years.

Great info and thanks for adding the photos! The freight house was, for me, the missing link that put all the pieces together so that the area and reconfiguration could be understood. The traffic volume and weight of the freight and then modern vehicles necessitated a new bridge, but also the entire discussion on the graded passings that both the city and CNYRR wanted to eliminate factored into the design. Apparently, the Baron Block with the Bucket of Blood tavern was one structure the city couldn’t wait to bid adieu to.