Madison Barracks Erected after Sackets Harbor Becomes an Important Military Installation During the War of 1812

Named after President James Madison, who visited during construction, Madison Barracks would be the logical progression to Fort Pike and Fort Tompkins. Both played a vital role in the War of 1812, as Sackets Harbor was attacked twice by the British, who were unsuccessful both times.

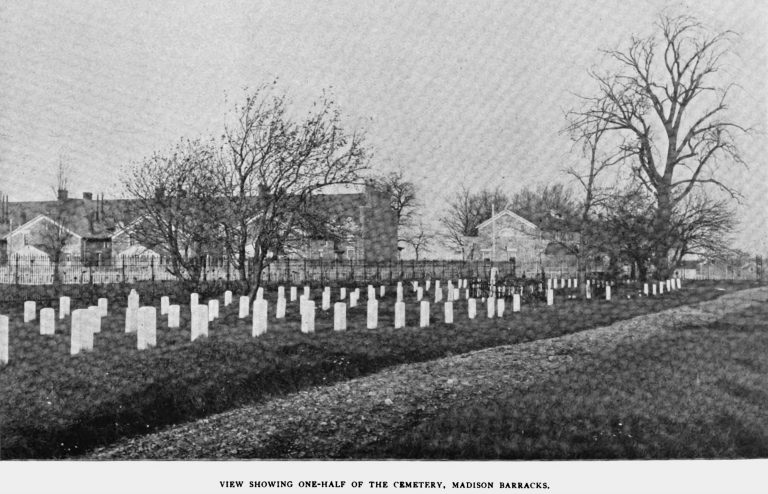

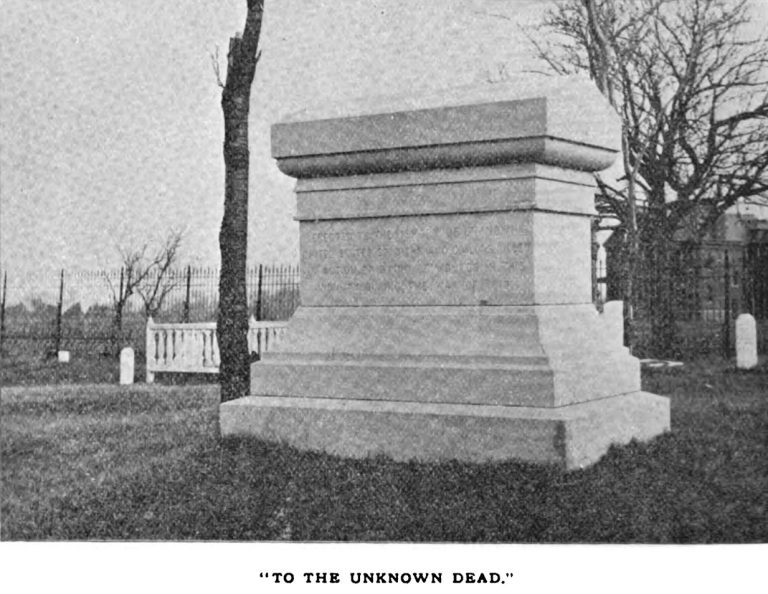

Fort Pike was named after explorer Zebulon Montgomery Pike, of Pike’s Peak fame, who also served with General Jacob Brown as a brigadier general during the War of 1812. Pike died in the Battle of York (now Toronto) in 1813 at age 34 and was buried in the nearby Military Cemetery at Madison Barracks.

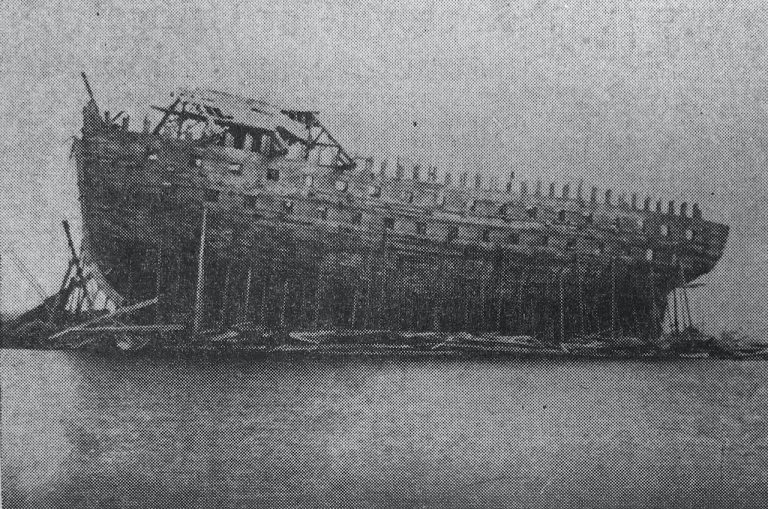

The War of 1812 ended with Police Commissioners from England and the United States declaring peace on December 24, 1814. However, it would be several months before the word reached Sackets Harbor, where the battle frigate New Orleans construction was already nearing completion at Naval Point. The New Orleans would sit unfinished for nearly 70 years, and the military ordered a large shiphouse built over it years later. The man tasked to build it would have the opportunity to erect something even larger first.

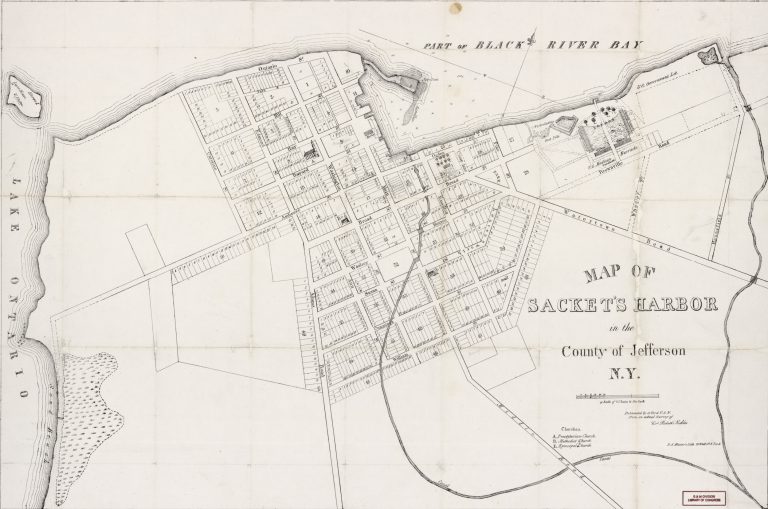

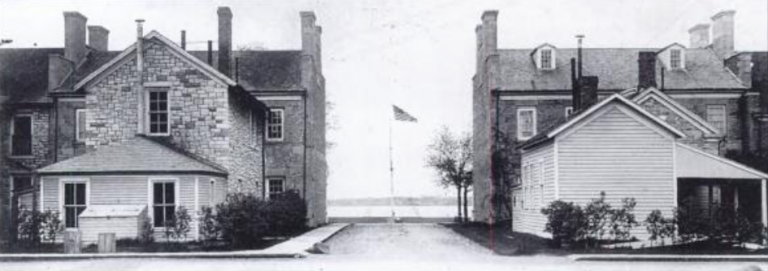

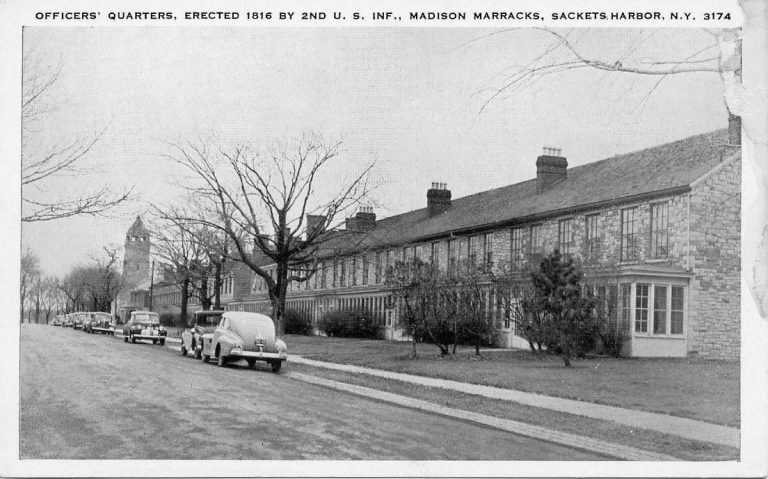

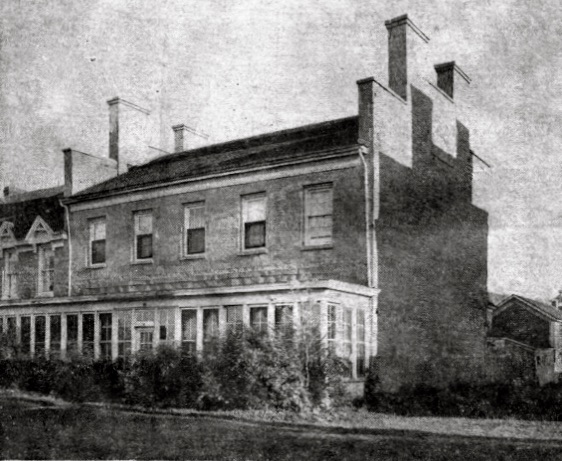

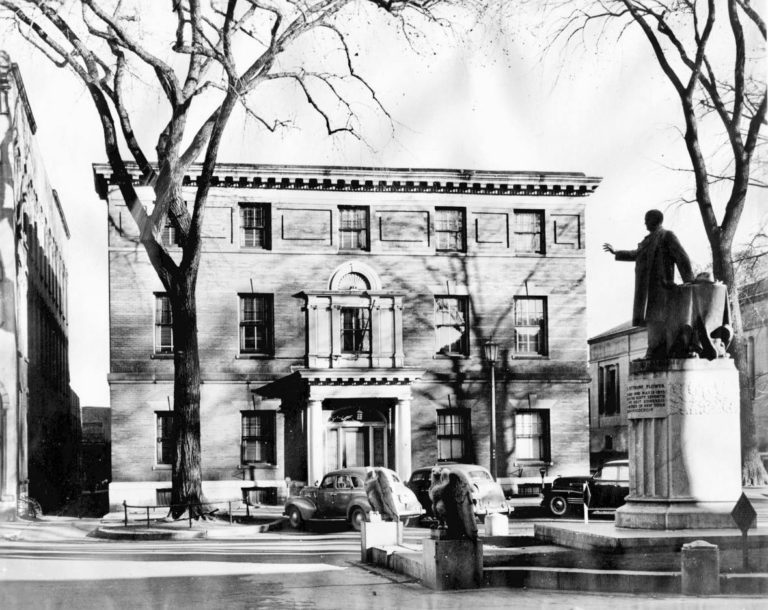

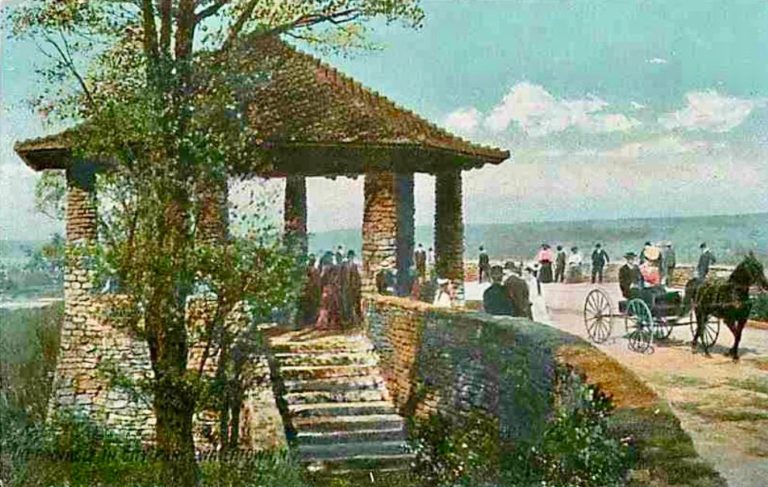

Well-known architect and builder William Smith was charged with laying out the grounds for the buildings at Sackets Harbor, which would become known as Madison Barracks. Construction began almost a year to the day after peace was declared in the War of 1812 and continued through October 1819. The estimated cost for the construction, with the stone buildings built from native limestone directly from the shores of Lake Ontario, was $150,000 (some reports would quote $85,000, but the $150,000 figure comes from sources closer to the actual date of construction.)

John A. Haddock would describe the construction of Madison Barracks, known later as “Stone Row,” in his book, Growth of a Century, as–

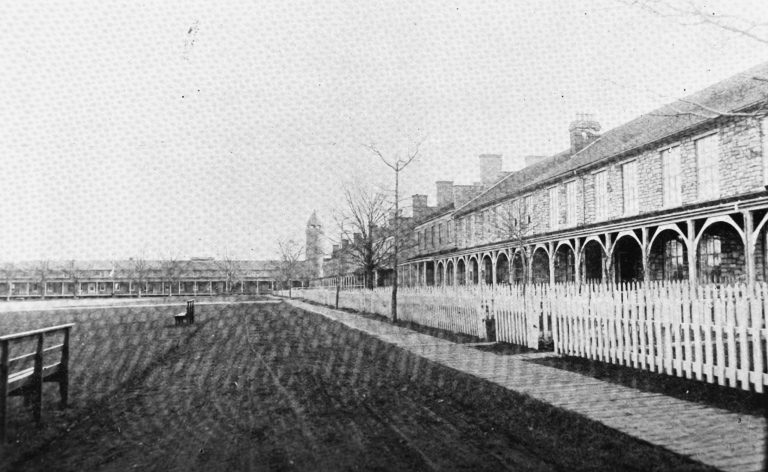

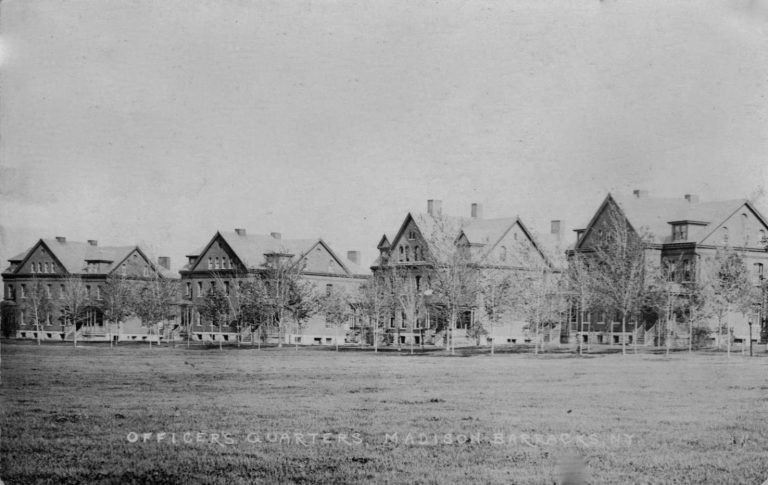

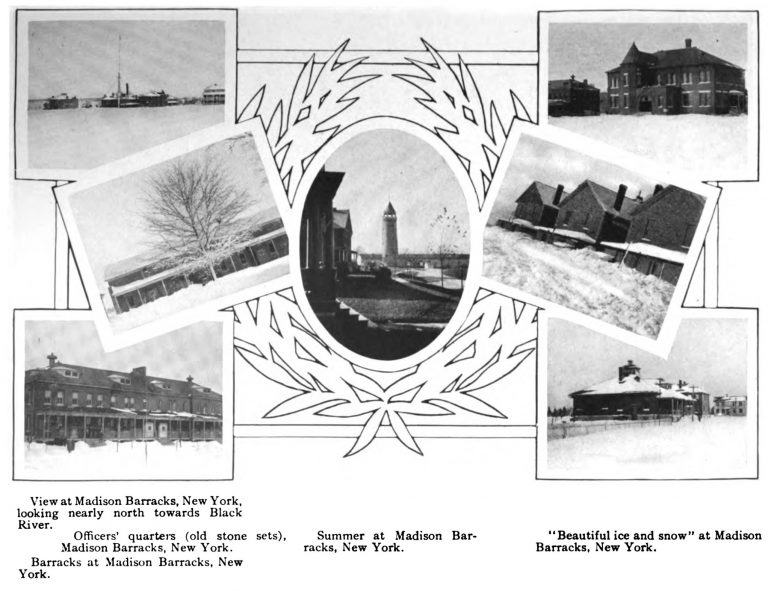

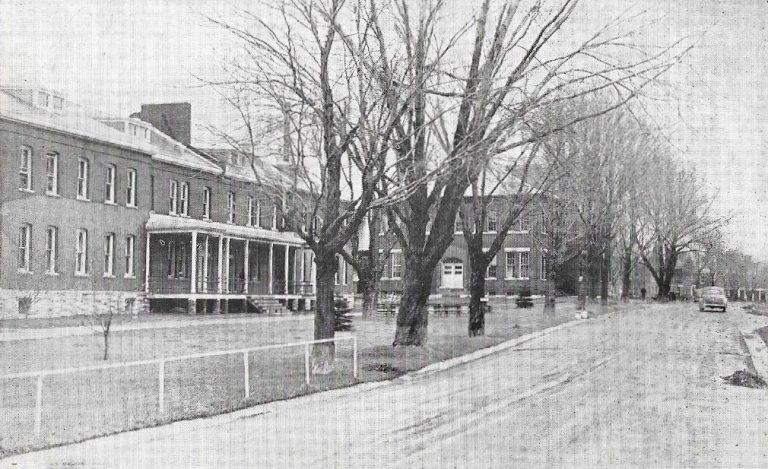

The principal buildings on the reservation were the officers’ and men’s quarters, guardhouse, hospital, the quartermaster’s and commissary’s storehouse, which are constructed of stone, and the administration building, ice house, etc., which were of wood.

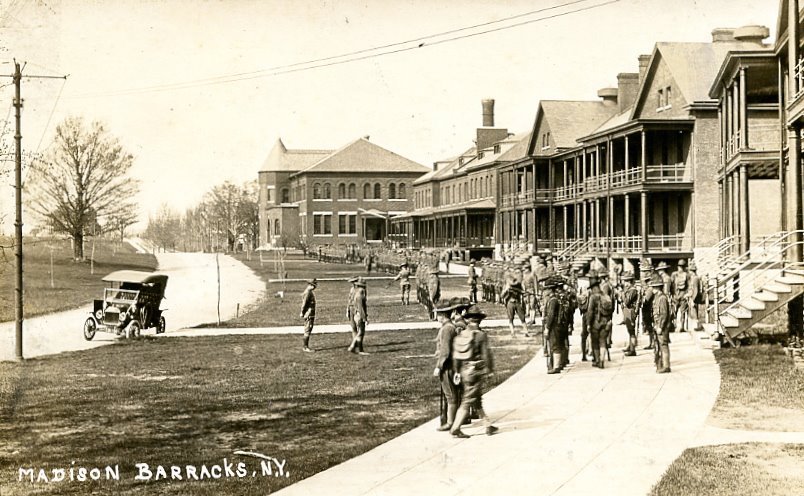

The officers’ quarters consist of two rows of buildings, each 217 x 83 feet. The men’s quarters two rows of buildings, one on each side of the parade, at right angles to the officers’ quarters. Each row is 452 feet long, 23 feet wide and two stories high. The hospital is at the northwestern limit of the reservation, about 50 feet from the water. This building, which is nearly square, with wings on the north and south, has recently (1894) been subjected to a thorough renovation and extensive repairs.

According to a 2019 Watertown Daily Times article by reporter Craig Fox, future President Ulysses S. Grant served two tours of duty as a junior Army officer, first from 1848 to 1849 and again in 1851, when he was accompanied by his wife and son. Twenty-one years later, in 1872, Grant visited the Thousand Islands as a guest at George Pullman’s summer cottage, before the construction of Pullman’s Castle Rest.

The much-publicized event and a major press corps retreat in Alexandria Bay a week earlier are credited with turning the region into a destination for the wealthy during the Gilded Age. He wouldn’t be the last figure from Madison Barracks to be associated with the Thousand Islands, as will be noted later.

At the start of the Civil War, local newspapers became the daily messengers for men who wanted to join regiments for service. Madison Barracks would be touted as “warm and comfortable” with the “good provisions and plenty of bedding” while enjoying the advantages of being near home as part of the Jefferson County Regiment.

THE PAY AS FOLLOWS

Bounty, $100, with term of service per month, $18; with board and clothing; Land Warrant, 160 acres; for traveling expenses, 50 cents per mile in returning home, amounting in all to $753.

Recruits may report themselves to I. M. BEEBEE, 1st Lieut., at Watertown, to S.A. MOFFETT or myself, W.R. Hanford, Capt. Co. A, Jefferson Rifles.

Capt. Handford’s Riflemen, Company A, Jefferson Rifle Regiment sought 30 men while Lieut. John A. Haddock, later ascending to Major and author of many historical books referenced on this website, including those of the Thousand Islands, sought appointments for Col. Lord’s 35th Regiment for a 20-month service. Enlistments would occur throughout the county in Larfargeville, Clayton, and Theresa.

Despite the promised pay, it wasn’t always delivered on time. On February 24, 1862, The New York Daily Reformer would detail the issues with regiments from Potsdam and Malone leaving for battle without pay. In other instances, payment was limited as sometimes it took an act to appropriate from state funds, and other times, it took national funds. With regards to Madison Barracks, the Reformer printed–

The soldiers, we learn, notwithstanding their temporary depression of spirits on pay-day, left Watertown with more buoyant hearts—the march to Watertown had enough of exposure and required enough of action to awaken muscular lite and set them in a glow corporeally and mentally; and the hospitality of our citizens demonstrated the fact that they still had friends to care for them.

The gloom lifted from their minds, and they departed with bounding enthusiasm and a more lively patriotism than had at any time animated them while contemplating a continued unexpected residence at Madison Barracks.

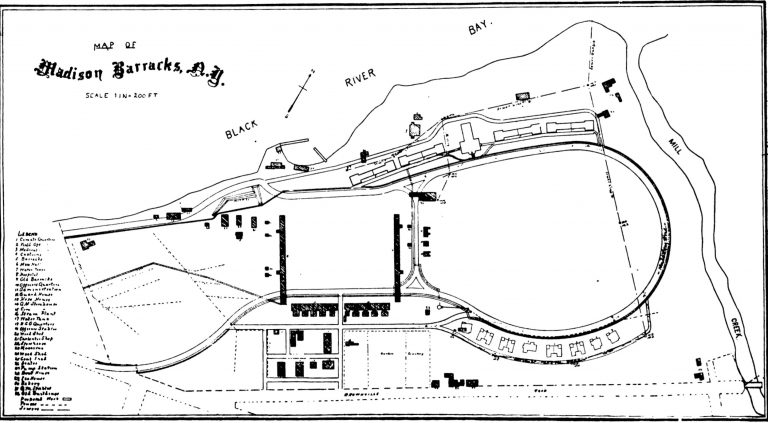

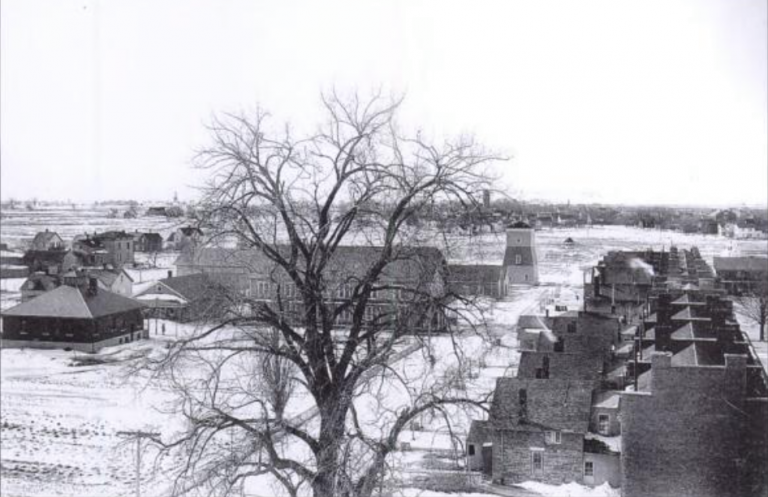

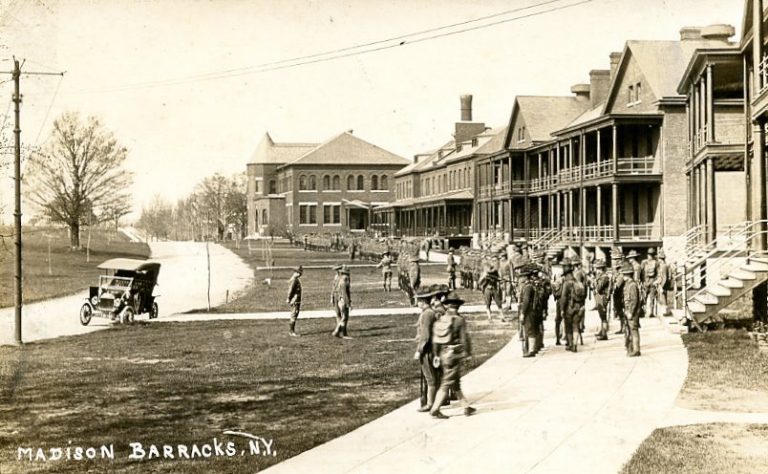

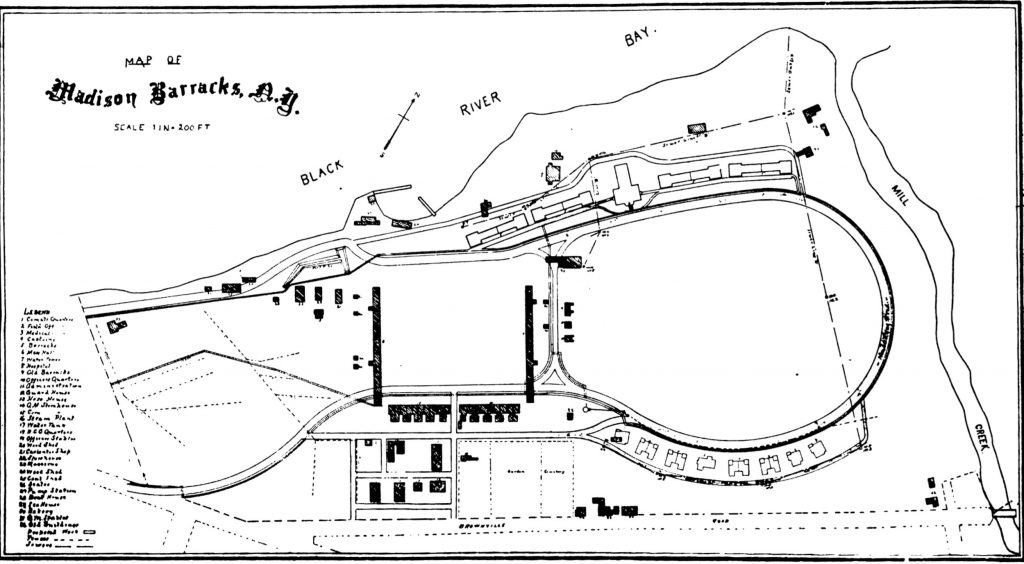

Around 1890, Madison Barracks underwent several improvements, as Major John A. Haddock noted: “When the plans of the United States engineer are fully carried out, it is expected we will have within our county one of the largest and most complete military establishments in the country.” The number of acres needed to accommodate the new construction would grow from 52 to 115. The map below shows the old portions of Madison Barracks in black and the new, or still under construction, structures in white.

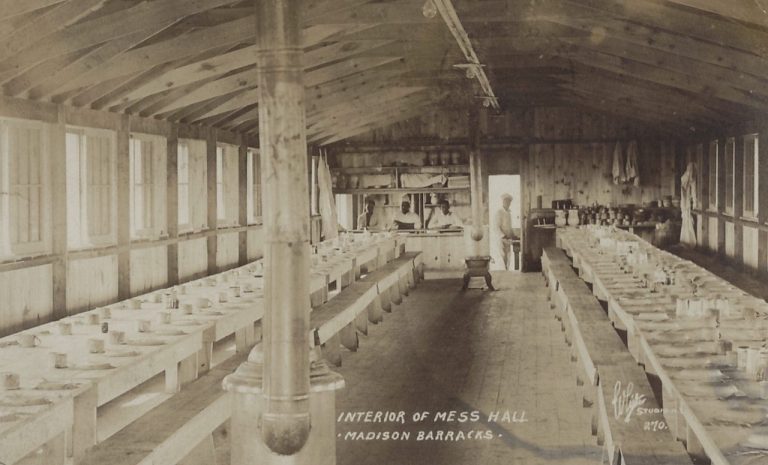

Major John A. Haddock wrote the following improvements being made–

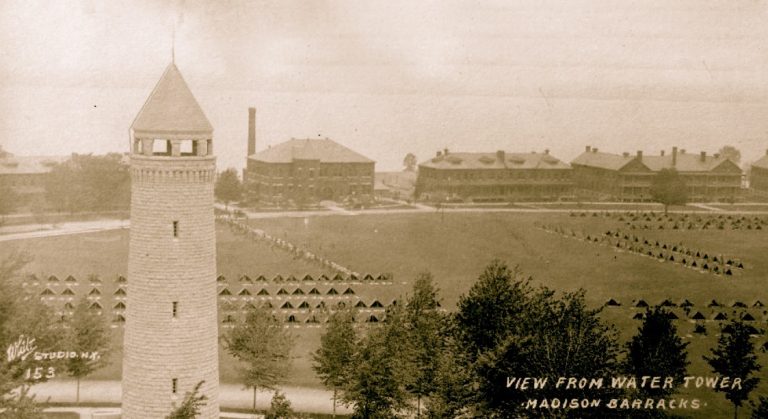

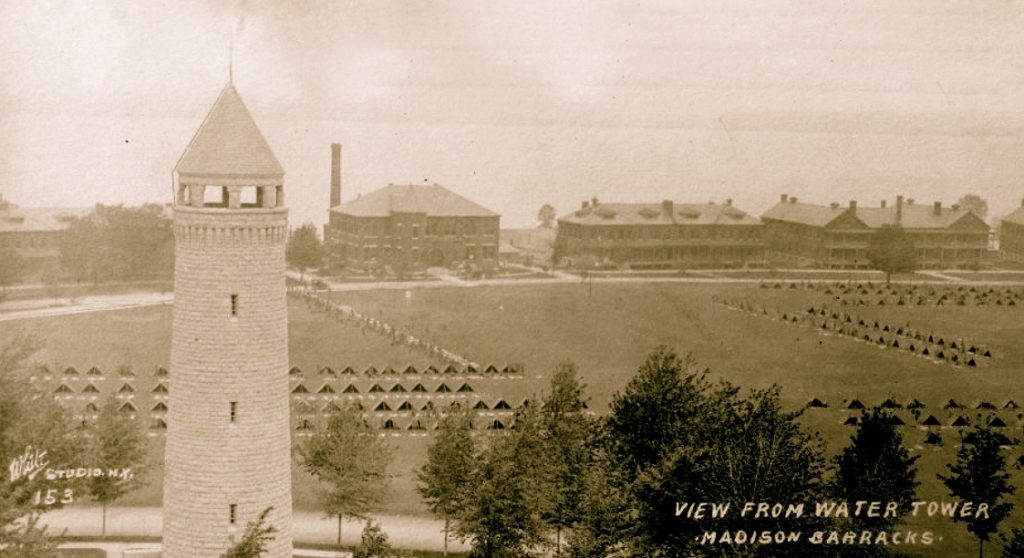

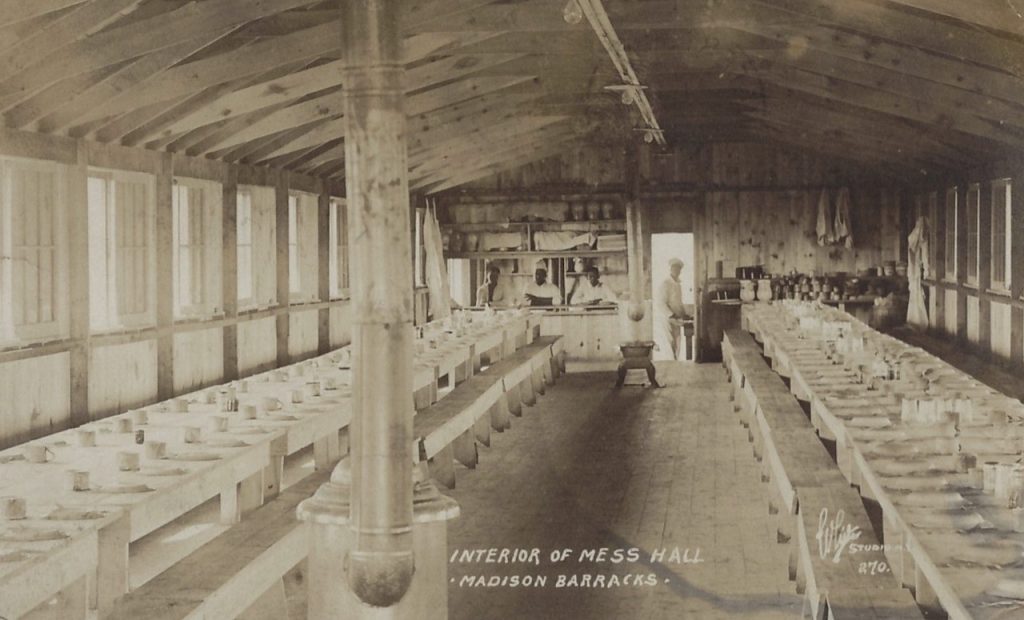

The plans for the new buildings include a mess hall, costing $38,000, in which 400 men can be fed at once; four double infantry barracks, which are outlined on either side of the mess hall at the top of the map; four double sets of captains’ quarters, and four single sets for field and staff; a water tower and general water works plant, costing $24,000; a heating plant for the officers’ quarters, costing $8,000, and a central steam plant, costing $16,000; a sewerage system, costing $4,250, and roads and walks, costing $8,000.

About half a million dollars have been expended here in building and repairing during the past 11 years.

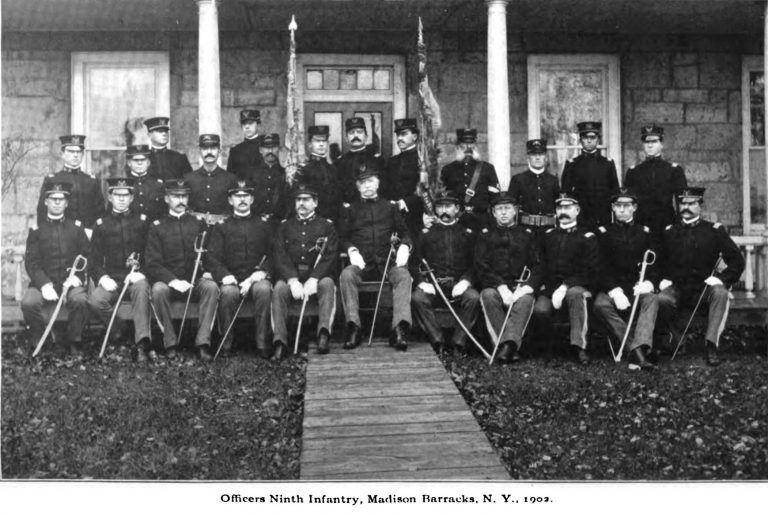

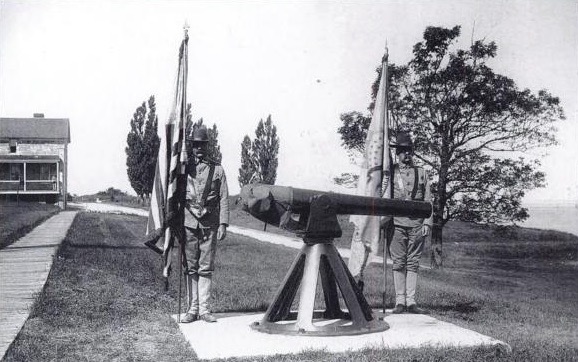

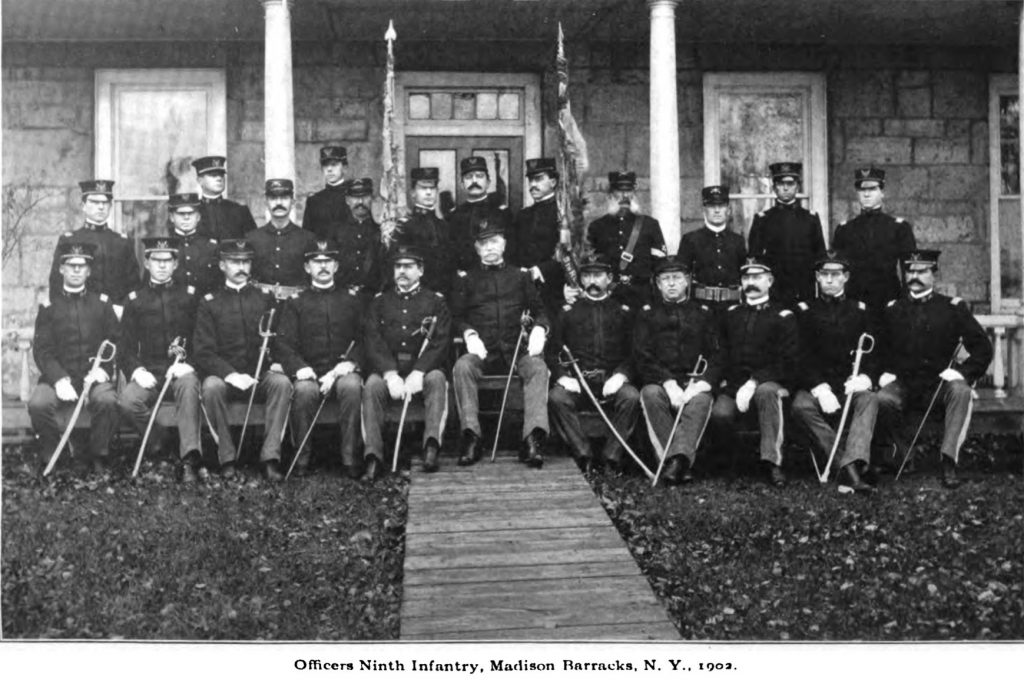

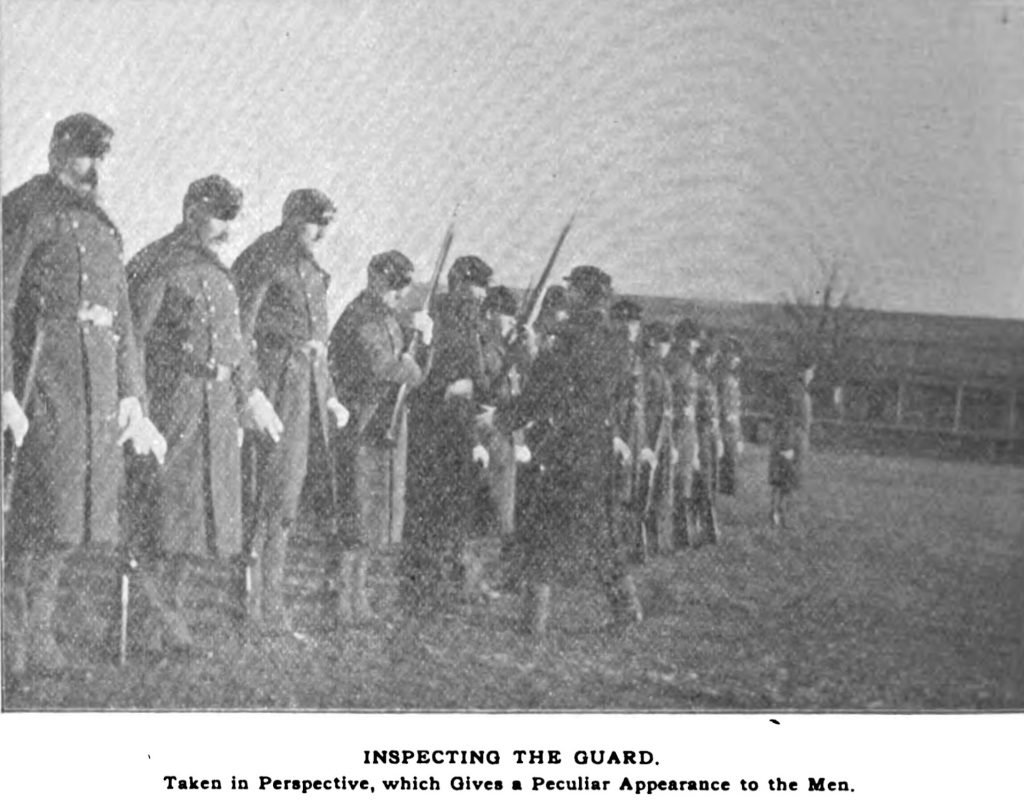

In 1892, Madison Barrack’s most famous regiment, The 9th Infantry, aka “The Fighting Ninth,” would be stationed there. According to the U.S. Army Installation Management Command’s official website—

During its stay at Madison Barracks, the 9th Infantry Regiment was involved with the Spanish-American War, The Philippine Insurrection, and the Boxer Rebellion in China. During the battle to capture Tientsin in China, the 9th Infantry Regiment was engaged in deadly combat. The regiment commander, Col. Emerson H. Liscom, was fatally wounded while recovering the colors from the wounded color bearer of the regiment. Before Liscom died, he handed off the colors to the adjutant with his final command to the Soldiers: “Keep up the Fire!” The fighting continued, and the regiment was successful in its attack.

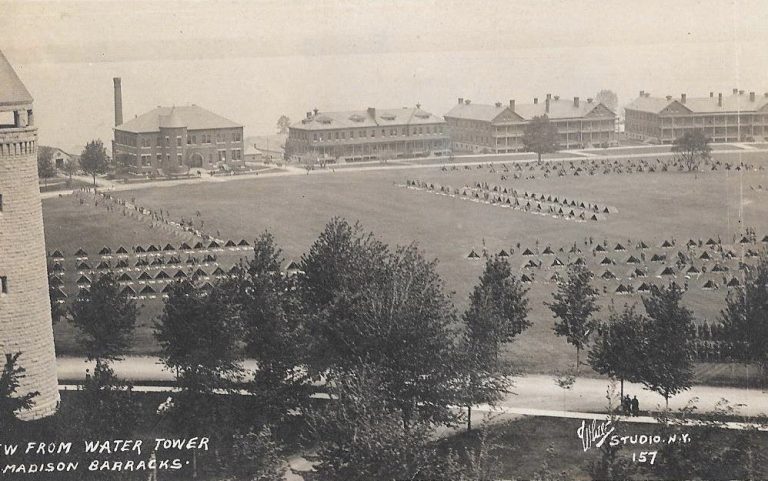

When service in the Pacific was over, the 9th Infantry Regiment returned to Madison Barracks. Affixed to the water tower, one of the most prominent landmarks on the military post, is a large plaque on which are listed the names of Soldiers of the 9th Infantry Regiment who lost their lives in service of Cuba, the Philippines and China between 1898 and 1907.

On July 12, 1902, The fighting Ninth would return from the Spanish-American War in Cuba, the Boxer Rebellion in China, and insurrection in the Phillippines. The soldiers marched in Watertown, to City Hall, Coffeen, and Massey Streets, down Clinton, Sherman, and Ten Eyck Streets before proceeding to Keyes Ave, Franklin, Academy, and Washington Streets before re-entering Public Square, going around it once again before heading to the Armory on Arsenal Street.

The Watertown Daily Times reported on the event: “The gaiety and patriotism exhibited by the charged-up Watertownians has seldom been repeated. The day was July 12, 1902, and the spirit was that of a holiday.”

Amongst the Fighting Ninth would have been Arthur Bonniecastle, a young man of Indian descent from Oklahoma, born to an Indian named Me-Tse-He. He would leave school early, join the Fighting Ninth in 1900, and later become the Chief of the Osage Indian tribe in Oklahoma. Arthur Bonniecastle received his name from the novel of the same, written by Dr. Josiah Gilbert Holland in 1874, who named Bonnie Castle in Alexandria Bay after the titular character of the novel. Dr. Holland has a street and library named after him in Alexandria Bay, having played a role as one of the earliest settlers and philanthropists in the region.

In 1906, Madison Barracks was under the command of Col. Philip Reade, who actively pursued new training grounds in the area. Working with various community leaders throughout the North Country and the Watertown Chamber of Commerce, that training ground was initially named Camp Hughes after New York Governor Charles E. Hughes.

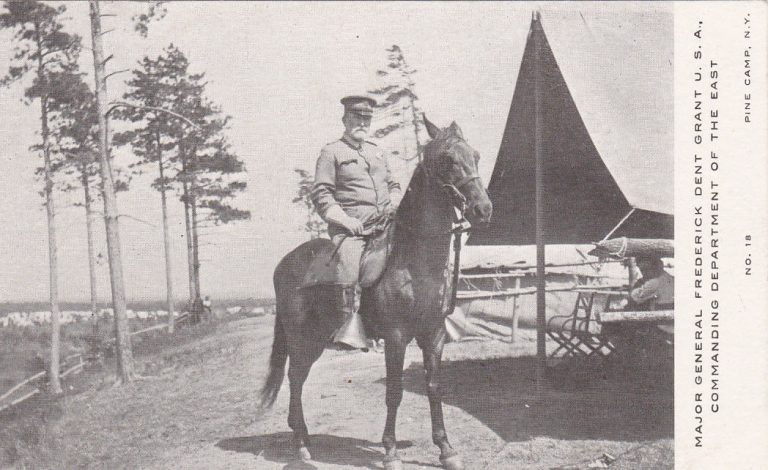

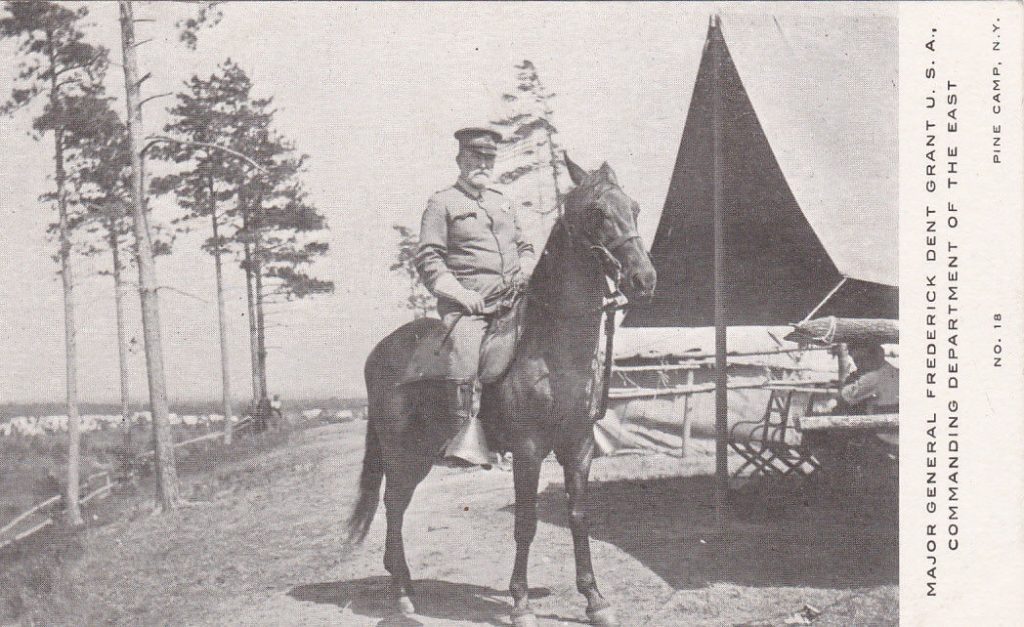

Camp Hughes would be a temporary tent encampment, but the following year, it became known as the Camp at Pines Plains, later simply Pine Camp, after Brig. Gen. Frederick Dent Grant, the oldest son of President Ulysses S. Grant, led thousands of soldiers to the area north of the Black River. He found it such an ideal place for training money was allocated, and the land was purchased for the newly anointed Pine Camp, which would eventually become Camp Drum and then Fort Drum.

With the advent of Pine Camp, Madison Barracks’s days appeared to be numbered. Money, facilities, and troops were allocated to the new installation, while Madison Barracks, once amongst the largest military installations, remained an active military installation through the end of WWII and ceased operation in 1947.

The barracks remained vacant for some years thereafter, being added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. Four years later, Madison Barracks would be purchased by North Barracks Development Co., Inc., owned by Frank Augsbury of Ogdensburg, who would work with developers and approve a $5 million plan to renovate the buildings for use as a community. The restoration called for controlled blazes on some of the structures, such as the “new” hospital, that had no current value and couldn’t be rehabilitated for the associated plans.

Thanks to those restoration efforts that began over forty years ago, Madison Barracks is a thriving community, best described from its website as featuring–

Rehabilitated and new residential housing units in dignified architectural harmony with existing structures. Single family homes, apartments, townhouses have vitalized a locale notable for serenity and beauty. This place offers its residents, guest and visitors an exceptional blend of recreational, social and educational activities within the site.