Boldt Castle: The Heart of the 1,000 Islands

The crown jewel of the 1000 Islands Gilded Age, Boldt Castle on Heart Island began construction in 1901 as a testament to George Boldt’s love for his wife, Louise Augusta Kehrer, rivaled only by perhaps his despair upon her death in 1904 when the incomplete castle was abandoned. Boldt, the proprietor of the Waldorf-Astoria in New York City, would cease construction and never return, leaving the castle to bear both the elements of time and weather unfinished as if it were his own heart that stopped beating.

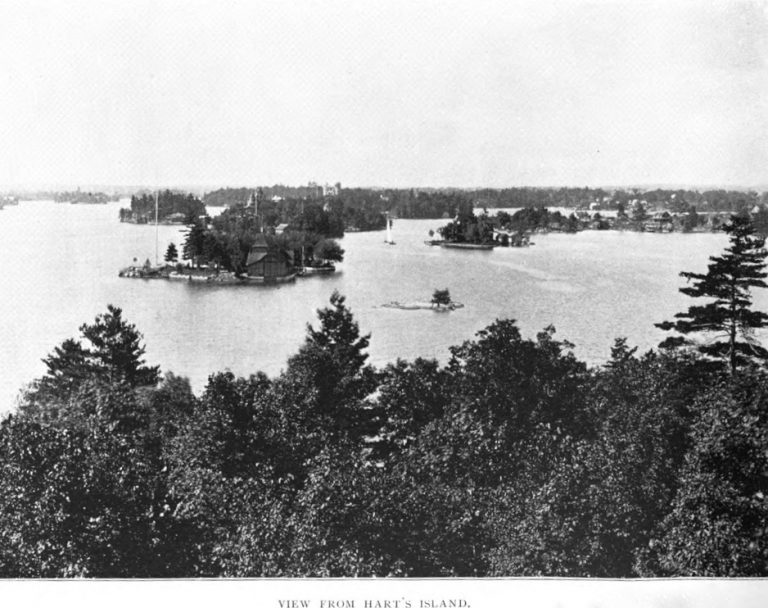

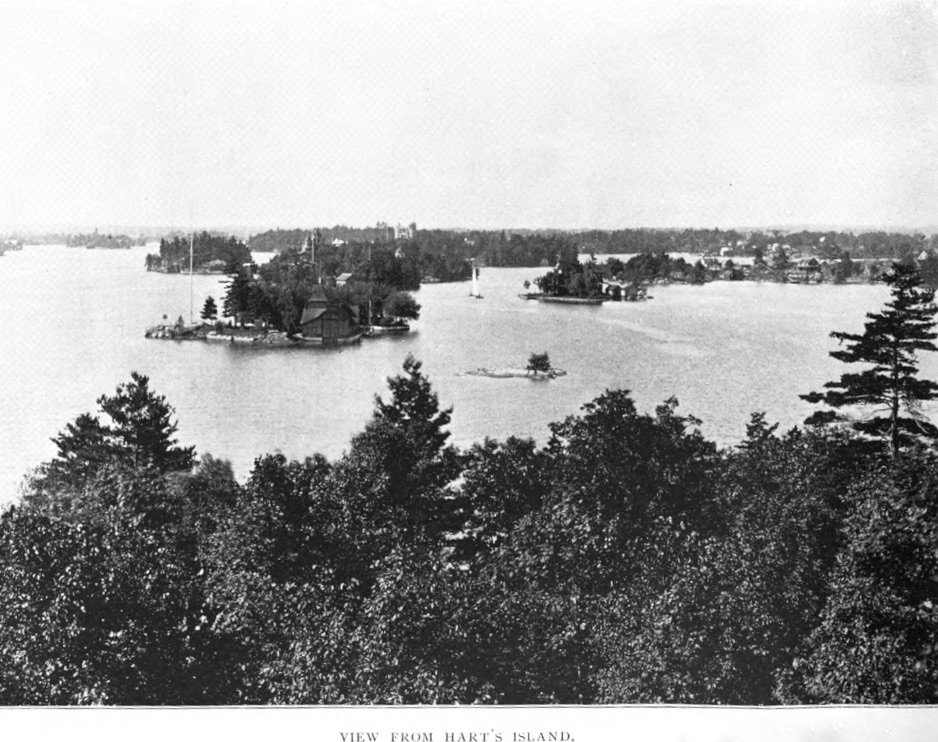

The island’s story starts long ago but began in earnest in 1871 when it was known as Hemlock Island, opposite the Crossmon House at Alexandria Bay, N.Y. At that time, Elizur K. Hart, who less than a year later served a (very) short term in the New York State Assembly, purchased the island for a reported $100 and renamed it “Hart’s Island.” He then proceeded to build an 80-room wooden cottage. Hart later serve in the U.S. House of Representatives and pass away in 1893.

Between 1893 and 1895, George Boldt visited Hart Island, which had fallen behind on its maintenance and upkeep. Boldt would form a real estate venture, incorporating it with several other individuals into the St. Lawrence River Real Estate Association in 1895 with a capital of $20,000. The names of the other directors were big: William C. Brown, Charles G. Emery, Edward Dewey, E. R. Bolden, Charles I. Hudson, James C. Spencer, James H. Oliphant of Brooklyn, and George M. Pullman of Chicago.

On July 1st of 1895, the Watertown Daily Times reported the sale of Hart’s Isle–

The Waldorf Hotel Managers Purchase It For $20,000

Alexandria Bay, June 28 – Hart’s isle, opposite Alexandria, has been sold to George C. Boldt and F. W. McCormick, of the Waldorf Hotel, New York. The price paid is said to be $20,000. The island is one of the most desirable in the river. It is five acres in extent, is high above the water and has every advantage for an excellent summer home.

It was the property of the estate of E. K. Hart, of Albion, N.Y., but has been unoccupied for some time. Many bids have been made for the property by prominent eastern capitalists, but until this deal was consummated all were unsuccessful. The purchasers will immediately begin to beautify the island by the erection of a fine summer residence and in various ways will make this naturally prominent island one of the most picturesque in the river.

One of the first things on George Boldt’s agenda was to change the island’s name from Hart Island to Heart Island.

By mid-July 1897, Boldt had entirely rebuilt the wooden cottage on Heart Island and constructed a new boathouse, landscaping, and walks around the island. The Watertown Daily Times reported his efforts, costing an estimated $100,000 at the time, had “so improved the island that one would hardly know the old place.” In addition to his property, Boldt purchased a tract of land on what was then still known as Wells Island (Wellesley Island today), where he built a bicycle track.

The following year, in October 1898, George Boldt had plans drawn up for a large, elaborate boat house on Heart Island, where the former Westminster Park warehouse once stood. The North Country would have to wait just short of another year to see how big and elaborate George Boldt’s vision for his island was.

In September of 1899, the Watertown Daily Times reported—

BOLDT’S CASTLE

A New Place To Be Built

As soon as Mr. Boldt took possession of the property he commenced the improvements which bid fair to make his summer home rival those of the Vanderbilts.

The first wonder of the architect’s skill which greets the summer visitors is the unique and antique Alister tower, which has been in process of construction for two years under the efficient supervision of S. G. Pope, the architect and builder of George M. Pullman’s Castle Rest. The plan of this tower was first conceived by Mr. Boldt while on a tour of the Rhine. The castle is an exact reproduction of a tower on this castle-lined river whose castles were built by King William, the German emperor.

There are six summer houses, built of rustic stone and lined with cork bark procured in South America at enormous expense. The abutments of stone are allowed to extend through the roof and flower beds are placed on their tops.

The residence, although very presentable, is to be torn down and a castle which will be in keeping with other accompaniments is to be constructed. Many of the ideas as to improvements are original with Mr. Boldt and these are executed regardless of expense.

1900 proved to be a busy year for Boldt’s ambitious projects. Work began on the large yacht house on the island. In April, Boldt procured three tracts of land on Wells Island for an undetermined use for a total of over $7,500. A few months later, he added yet another parcel for nearly $3,000.

In late August, plans for Bold’s “mammoth cottage” were completed by architect William Hewitt of Philadelphia, with an estimated cost of $200,000 combined with expenditures totaling $400,000 for the work already completed. Per the Watertown Daily Times, this included “the tower, which is a reproduction of a tower on the Rhinê, cost $15,00, the powerhouse, $40,000, yacht house, $50,000 and the peristyle $25,000.” It was further explained–

The building will be constructed on the Italian renaissance style of architecture, four stories high, with four small towers 40 feet high, grouped about two larger towers 60 feet high, while the main tower will rise to a height of 75 feet, forming the main figure of the surrounding turrets. The interior of the house will consist of 50 sleeping rooms en suite, with baths and porcelain wash stands. The main dining room will be in the old portion of the building, but there will be a private dining room in the new part. The library, parlor and ballroom will occupy a large portion of the new part.

At the time, it was believed that the castle would be completed in 1902 and cost around $2,000,000. Only days later, another effort was announced: to build a sea wall, 16 feet from the shore, around the island at a cost of $50,000.

Of note, a month earlier, in July of 1900, the Watertown Daily Times noted on the 17th that workmen had begun to tear down the cottage on Heart Island. Three days later, it noted, “The portion of the cottage on Heart Island which is to be removed preparatory for the erection of a new one is to be moved in sections and re-erected at the golf links on Wellesley Island, where it will be used for a clubhouse.” It has been reported for a long time that these sections were moved during the winter over the frozen river, but there’s no mention of this other than in July.

Work continued during the next two years, with various undertakings added to the list of accomplishments, such as a canal Boldt would have constructed on Wellesley Island between the mouth of Mud Creek, opposite Alexandria Bay, and Lake Waterloo. When he wasn’t working in New York City or inspecting the work of a small army constructing his summer home, Boldt busied himself dispelling rumors that he was building a hotel on the island and assuring people it was a summer home.

In August of 1903, Mrs. George C. Boldt, a socialite of the 1,000 Islands scene, departed for Germany for the remainder of the season. It would be the last time she visited the island, for she died suddenly in Manhattan on January 8th, 1904. The Watertown Re-Union noted she had been ill since the previous summer.

With Mrs. Boldt’s sudden death came the end of George Boldt’s vision for Heart Island. Work on Boldt Castle was halted, and the spark that lit the passion and inspired the work was gone. Instead of a testament to the love for his wife, Boldt Castle became a symbol of shattered dreams and broken hearts. Though George Boldt returned to the 1000 Islands many times until he died in 1916, he never set foot again on Heart Island (or so it’s said; newspapers of the day contradicted this.)

For 73 years, Boldt Castle sat abandoned on Heart Island, exposed to the elements, time, and the occasional vandal. In 1977, the Thousand Island Bridge Authority purchased Heart Island, Boldt Castle, and the yacht house on Wellesley Island for $1.00 under an agreement that revenue generated from its operation would go toward restoration.

While the first two floors have seen extensive renovation, some areas have not, though the facilities themselves are seemingly under some stage of renovation at any given time.

As of 2021, over $50,000,000 has been spent restoring Boldt Castle and its surrounding structures. This is a large amount of money invested in what has become a major tourist attraction in an area known for tourism.

Economic Impact On Region

According to Boldt Castle’s official website, an independent study was conducted in 2015/16 to assess the castle’s economic impact on the local region. The results were staggering: the $50,000,000 spent on its renovation since its acquisition in 1977 was well spent.

A summary from the website details the following:

- Boldt Castle draws nearly 200,000 visitors annually and has become a major international destination.

- Its operation generates over $46,000,000 annually in regional economic activity.

- Over 600 jobs have been created in the regional economy as a result.

- Local spending per visitor: $181 per average Boldt Castle visitor ($724 for a family of 4)

- Total Visitor Spending at Regional Businesses: $30.1 million in annual visitor spending

- Impact on Economic Output: Additional $39.9 million in annual economic output

- Impact on Gross Regional Product (GRP): Additional $23.1 million in annual GRP

Note: a comprehensive economic impact report can be found on the official Boldt Castle website here.

The following is a short video from WPBS on the history of Boldt Castle, which includes a number of photos prior to restoration efforts.

Interesting Tidbit

A low-budget horror movie, Fear No Evil, was filmed in 1979 and released in 1981. It used Boldt Castle as its narrative centerpiece. Young filmmaker Frank LaLoggia from Rochester, N.Y., financed the film with his cousin, Charles, who, having seen the castle, thought it the perfect place to base a story. Although it was a relatively campy movie, LaLoggia struck a minor cult classic with his follow-up, The Lady In White, several years later.