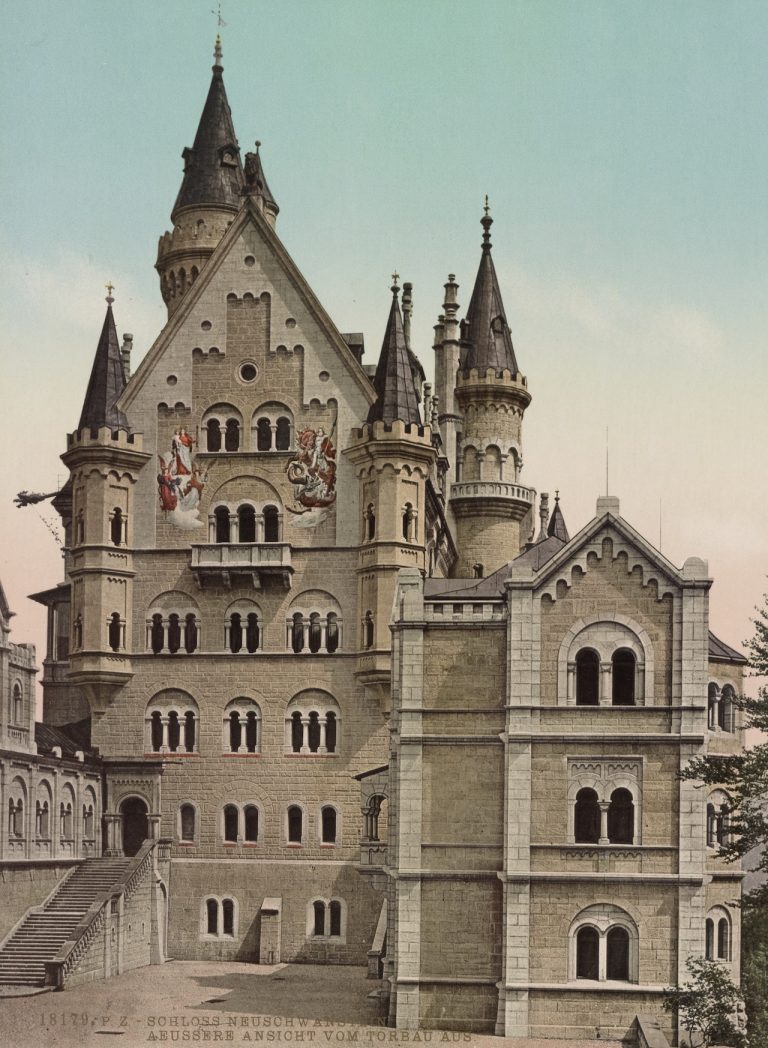

Neuschwanstein Castle: Construction Started in 1869 But Never Completed For King Ludwig II Of Bavaria

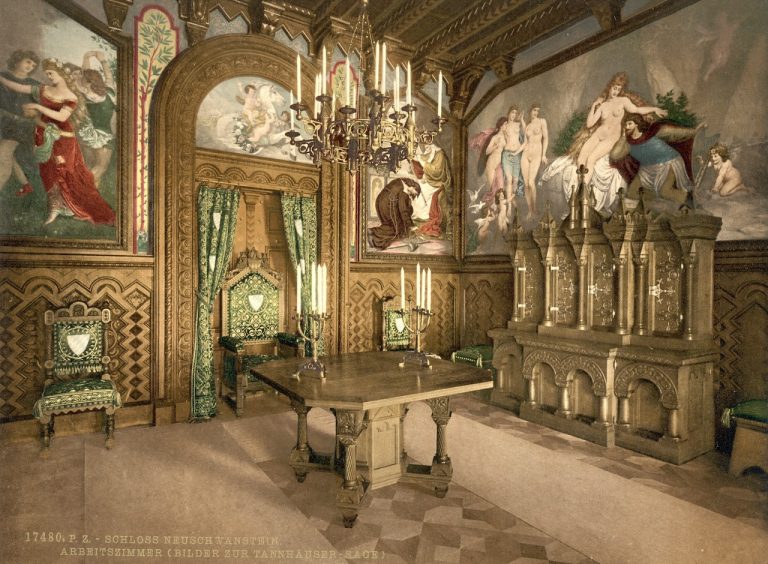

Construction on Neuschwanstein Castle started in 1869, six years after King Ludwig II took the throne at 18. An ode to Richard Wagner, whose opera works the King adored to the point of becoming his patron, Neuschwanstein Castle, along with the King’s other numerous fanciful projects and his lack of involvement in the state of affairs, amongst other things, would put him so far into debt that he would be removed from power and die under mysterious circumstances shortly thereafter.

Born in 1845 to Maximilian II of Bavaria and Marie of Prussia, the Crown Prince and Princess of Bavaria, Ludwig II spent much of his childhood in the rebuilt Schwanstein castle across from where Neuschwanstein would eventually be built. Maximilian II would acquire the old Schwanstein castle ruins in 1832 and rebuild it over the next two decades, becoming King in 1848, adding onto the structure, and eventually changing its name to the current Hohenschwangau Castle.

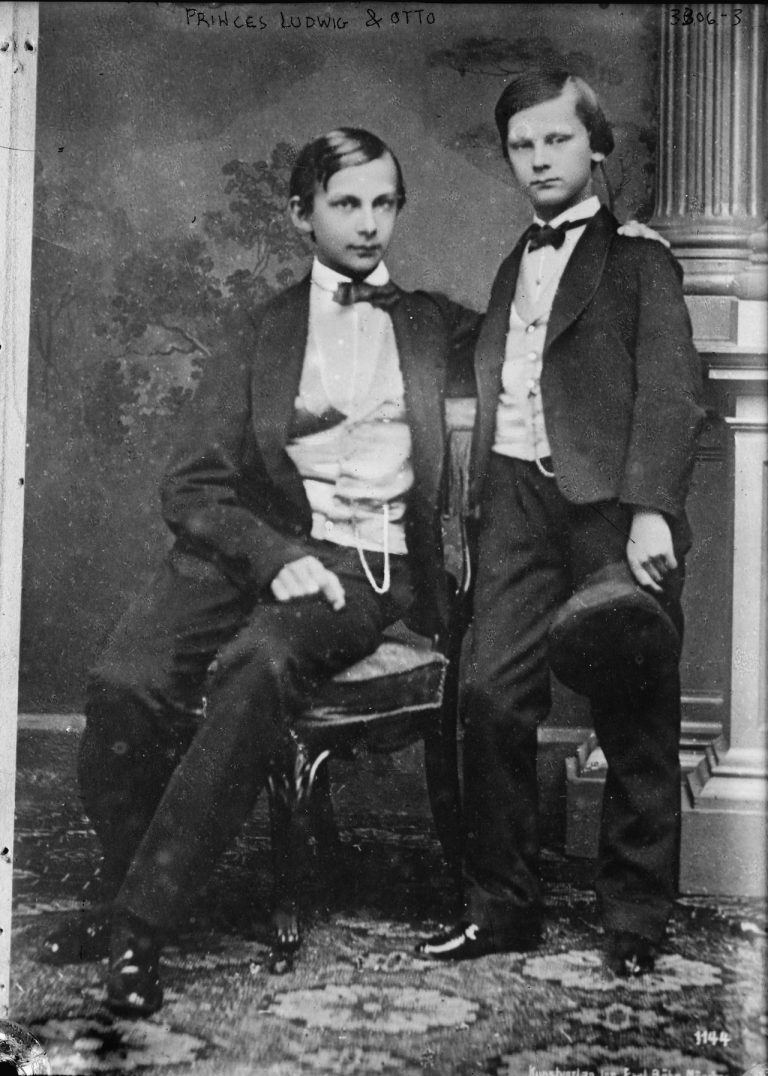

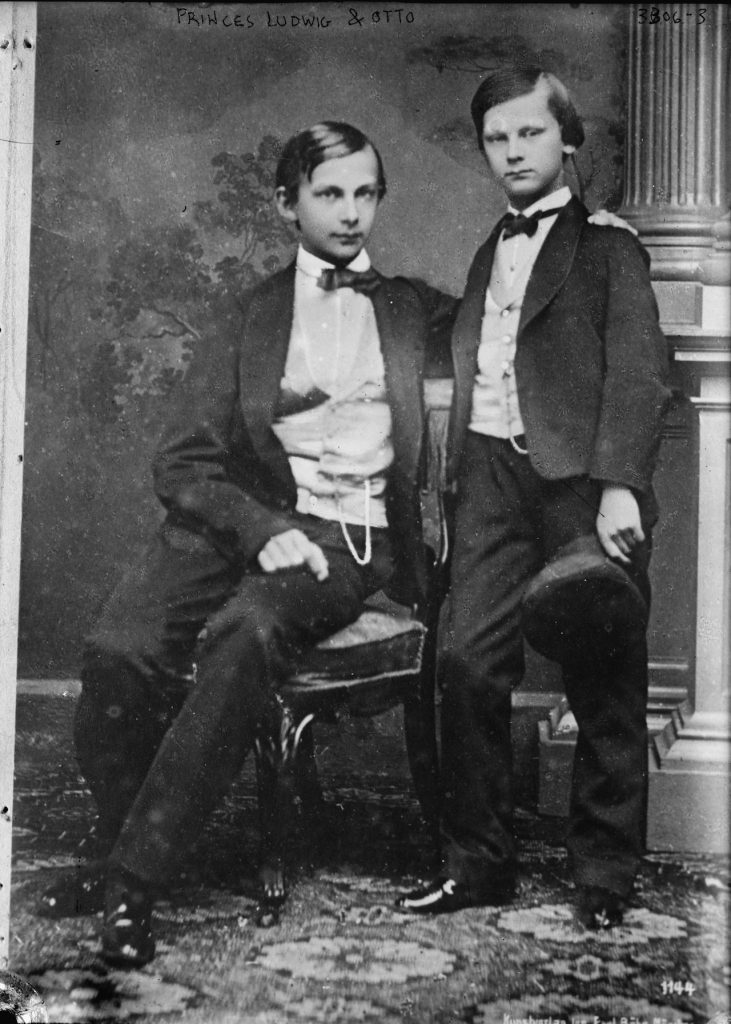

As a youth, Ludwig II wasn’t close to either of his parents and showed little interest in his father’s rule of the land. Rather, he and his younger brother Otto spent most of their time away from their parents and with servants and teachers.

In 1863, at 16, Otto served in the Bavarian Army and was appointed sub-lieutenant. At about the same time, Ludwig II would discover the operas of Richard Wagner, and the fates of both would change course forever.

It is often remarked that Richard Wagner’s latter half of his career after exile wouldn’t have existed if not for Ludwig II. Likewise, Ludwig’s thrust onto the throne of Bavaria at an early age would not have happened if it weren’t for the unexpected death of King Maximilian II after a brief illness at the age of 52. Ascending the throne at the age of 18 without much preparedness and already with a heightened sense of imagination and fantasy, Ludwig II, who was said to have homosexual tendencies, became enamored with Wagner and his work.

Wagner had recently been freed from exile, and a broken marriage to Christine Wilhelmine “Minna” Planner after his affair with Mathilde Wesendonck was exposed. Saddled with substantial debt, his fortunes soon changed upon meeting the enamored King Ludwig II who was all too eager to help pay it off. In addition, Ludwig II would also propose to stage in Much Tristan, Die Meistersinger, the Ring, and the other operas Wagner had in the works.

As a result, Wagner’s return after a 15-year absence with Tristan und Isolde proved to be a great success, though his adulterous transgressions appeared to have followed him to much controversy as an affair with a married woman 24 years younger resulted in an illegitimate child.

The scandal rocked Munich to the point that King Ludwig II had to ask Wagner to leave, but not after seriously considering joining him and abdicating the throne. Wagner persuaded King Ludwig II not to, but it was only the beginning of multiple challenges the young king would face.

In 1866, King Ludwig II sided with Austria in the Austro-Prussian War, which would last only one month and 8 days. It was a humiliating defeat for the young king with a power shift to Prussia. Forced to sign a mutual defense treaty with Prussia, Bavaria, and King Ludwig II would be pulled into the Franco-Prussian War just a few years later.

Meanwhile, Ludwig II would also find himself fighting another, more personal battle. It was said that the greatest stress for the king during this time was to produce an heir to the throne. In 1867, he would be engaged to his cousin, Duchess Sophia of Bavaria, the younger sister of perhaps Ludwig II’s closest confidant throughout his life, Empress Elizabeth of Austria.

At the center of Ludwig II’s and Sophia’s relationship would be their shared appreciation for Richard Wagner’s work. After postponing the wedding numerous times, Ludwig would call it off in October, his message to her afterward reportedly using Wagner’s characters, Heinrich and Elsa from his opera Lohengrin, to convey his feelings, an act that perhaps blurring the lines between fantasy and reality.

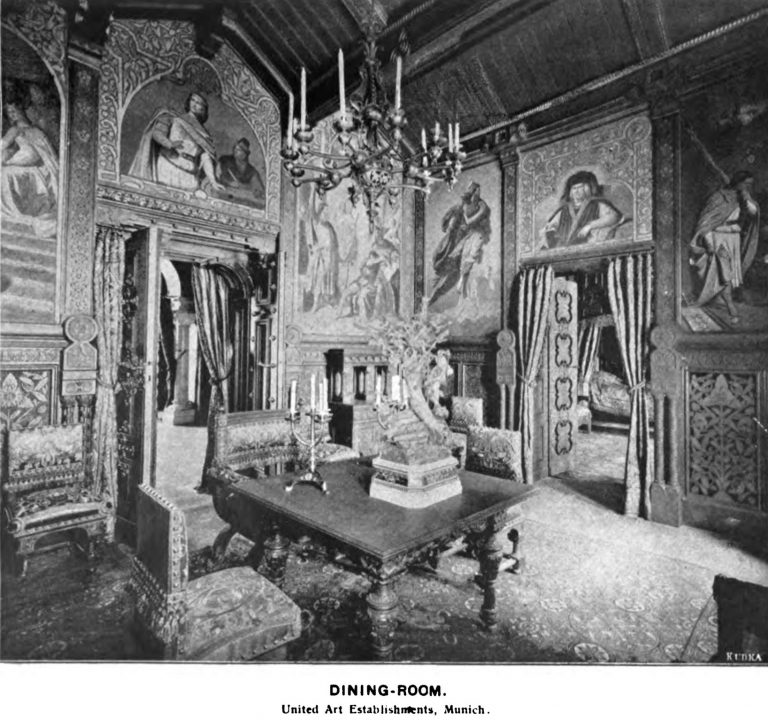

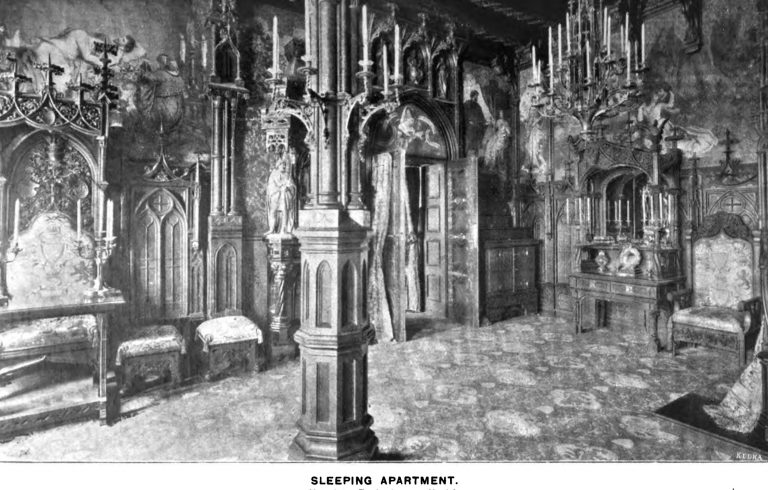

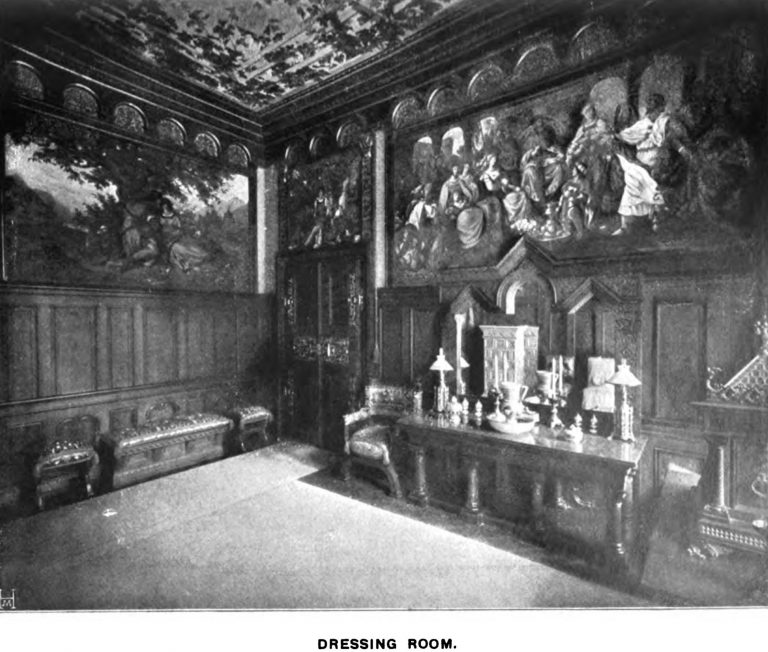

After the failed relationship, Ludwig II would never marry or have another mistress for the remainder of his life. Instead, he would begin to withdraw and focus on his creative endeavors, which would see him begin to carry out his plans for New Hohenschwangau Castle, which he envisioned to be built upon the ruins of twin castles Vorderhohenschwangau and Hinterhohenschwangau.

For clarity, Neuschwanstein Castle was named as such only after the death of King Ludwig II. Schwanstein Castle, which the aforementioned Maximilian II rebuilt and added onto extensively, would adopt the name Hohenschwangau Castle once Ludwig’s New Hohenschwangau Castle was christened “Neuschwanstein,” being the literal translation of “new” Schwanstein, instead.

Meanwhile, King Ludwig’s brother Otto would partake in the Austro-Prussian and the Franco-Prussian wars, ascending to the rank of Captain in the first war and then Colonel in the second war. Whereas King Ludwig was introverted and retreated into seclusion in the following years, Otto was more outgoing and vocal until the wars had taken a toll and sent him to a depressive and anxious state.

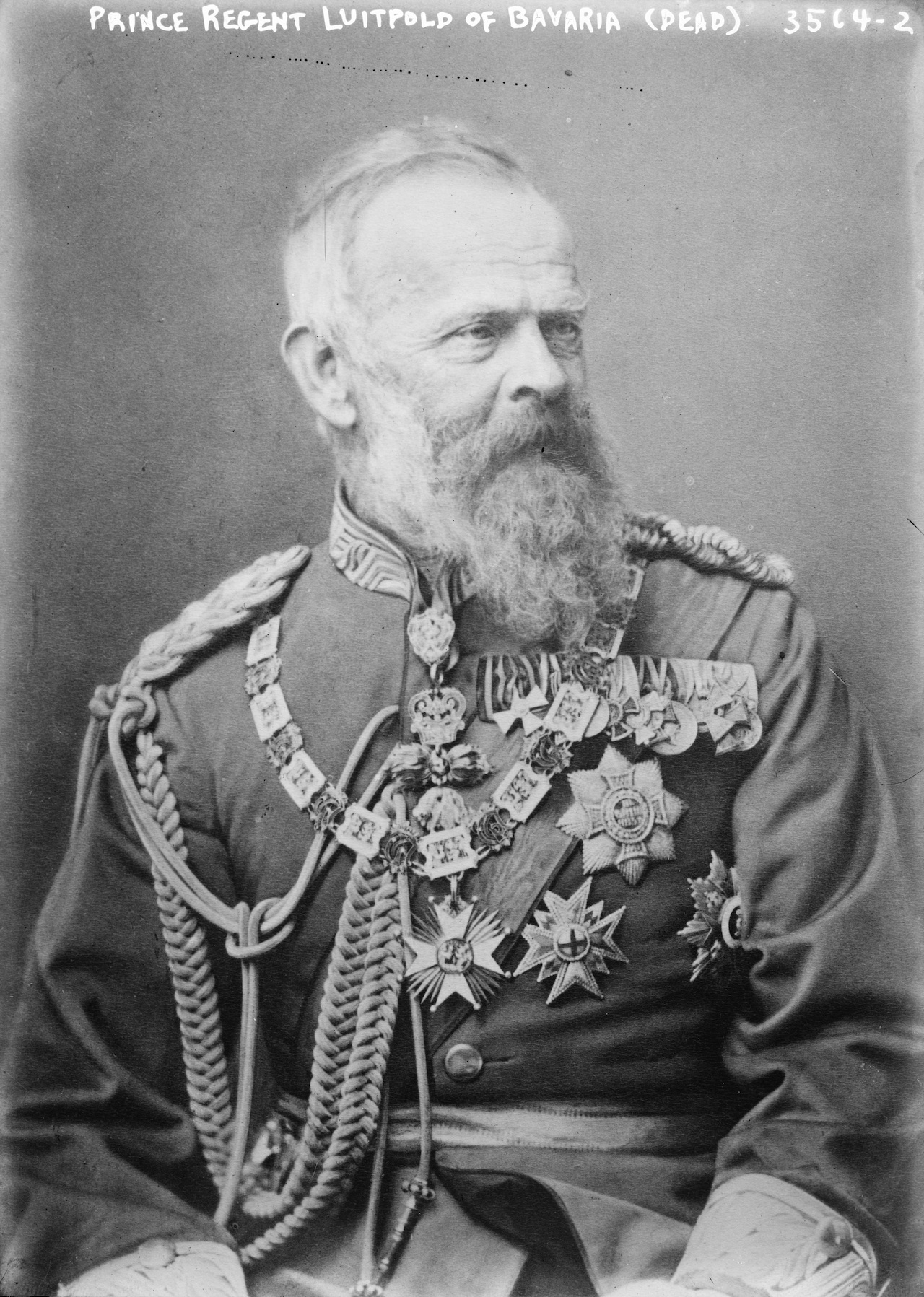

In 1872, Otto’s physician, Dr. Bernhard von Gudden, declared Otto mentally ill. Only one year earlier, Otto would attend the proclamation of Wilhelm I as Emperor of Germany with his uncle Luitpold in the absence of King Ludwig II, who refused to attend. Luitpold, the younger brother of King Maximilian II, was pro-Prussia as was Dr. Bernhard von Gudden. However, King Ludwig II and Otto despised Prussia, putting them at odds with Luitpold and Gudden.

Otto’s diagnosis and subsequent isolation in Nymphenburg Palace in 1873 somewhat mirrored King Ludwig II’s growing seclusion. Nevertheless, despite his growing eccentric behavior, the king was popular amongst the Bavarian people whom he often frequented while traveling through the country.

These people directly benefited through many of King Ludwig II’s projects, bringing work and a sense of culture lacking into parts of the country that, albeit beautiful, were deemed poor. But alas, the King’s inattentiveness to the matters of the throne left the door, among other issues, would put him at odds with his ministers, who increasingly looked to Luitpold for leadership.

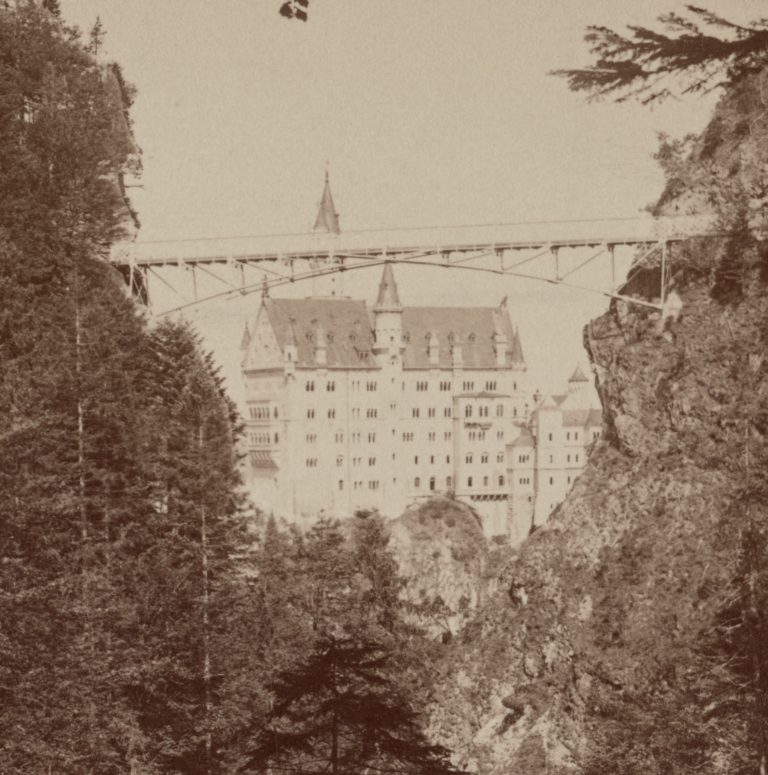

One of the ministers’ challenges was reigning in King Ludwig II’s spending. It is estimated that the costs of Neuschwanstein Castle, though mostly unfinished as it still stands today, much like George C. Boldt’s Castle on the St. Lawrence River, along with projects Lindhorf and Herrenchiemsee, would drain King Ludwig II’s funding.

According to sources and contrary to many’s beliefs, the King did not bring Bavaria close to bankruptcy. His funds grew substantially upon the death of the abdicated King Ludwig I, his grandfather, in 1868, allowing him to move forward with his plans. Other private sources provided aided in his projects, as well as a political favor to Otto von Bismarck. Neuschwanstein alone would cost approximately $51,000,000 in 2022 currency for work completed until Ludwig’s death. Nevertheless, the issue created conflict between the King and his ministers.

In 1875, Otto was confined to Schleissheim Palace for several years until his condition grew worse, for which he was moved to Fürstenried Palace in 1883 near Munich, where he would spend the rest of his life. 1883 would also see the death of Richard Wagner at the age of 69 from a heart attack. Despite it being a monument to his music, Wagner would never see Neuschwanstein Castle.

Richard Wagner’s timeless works have found their way into motion pictures, including the famous “Ride of the Valkyries” scene in 1986’s Platoon, directed by Oliver Stone. Clip: YouTube.

By 1885, King Ludwig II was 14 million Marks in debt as his projects, some of which were supposedly only to take a few years to complete, kept changing and growing more elaborate, all the while new ones were being planned. Yet, Ludwig continued to seek personal lines of credit from outside the country and Europe’s Royalty, refusing the advice of his ministers, who he began to feel were hindering his projects.

The ministers, fearing the King would strike to remove them first, would attempt to depose him from the throne with his uncle, Luitpold, who agreed on the condition that there was viable proof of Ludwig’s mental illness. Thus began the conspiracy to remove King Ludwig II from rule.

Gathering a list of eccentric behaviors from aids and personnel in close contact with the King, a report was generated and signed by four psychiatrists: Dr. Bernhard von Gudden, who headed the effort, along with his son-in-law, Dr. Hubert von Grashey, Dr. Frederich Wilhelm Hagen and Dr. Max Hubrich.

The report stated that King Ludwig II suffered from paranoia and was unfit to rule, despite none of the doctors ever having examined the King, let alone met him, except Gudden, twelve years prior. Dr. Gudden would, however, use the diagnosis of Ludwig’s brother Otto as justification. Other things other than royalty “run in the family.”

The first attempt to apprehend Ludwig by the commissioners at Neuschwanstein Castle failed. The King was alerted to the plan well enough and could have the local police protect him. On the second attempt, Ludwig wasn’t as fortunate.

Efforts to inform the public of the treasonous plan were sniffed out and squashed while the government publicly decreed the title to Luitpold of Prince Regent of Bavaria. It was too late when King Ludwig II finally attempted to escape.

Ludwig was seized and transported to Berg Castle near Munich by a replaced police force. The following day, Dr. Gudden and King Ludwig II would take an evening stroll around the grounds of the Berg estate and near the shore of Lake Starnberg – their second walk of the day. Who suggested the second walk is unclear, as is why the two went unaccompanied.

The result was the bodies of both men were found in shallow water near the shore a short time after they were due back. Ludwig’s death would be ruled a suicide, by drowning no less, despite an autopsy finding no water in his lungs. Dr. Gudden’s body showed a struggle with blows to the head and signs of strangulation. No witnesses to the event were found, and the police patrolling the area reported having not heard nor seen anything unusual.

Like most high-profile deaths under mysterious circumstances, many theories and conspiracies have ensued in the 136 years since. One particular account was from Ludwig’s personal fisherman, Jakob Lidl, who claimed to have witnessed his shooting but was sworn to an oath never to mention it. Hiding in bushes with his boat, he was to get the King and rendezvous on the lake with loyalists. Lidl had never mentioned this per his oath, but his written account was found after his death.

The telling of the events would contradict any findings in the autopsy report. Years later, a Countess having a tea party supposedly showed her guests a grey coat that King Ludwig II was said to have been wearing at the time of his death. It had two bullet holes in its backside. The coat itself would be destroyed in a fire some years later, but the recounting of the events, whether true or not, has lived on over the years.

Upon King Ludwig II’s death at 41, Otto ascended the throne and became King of Bavaria in accordance with the Wittelsbach succession law. Already deemed unfit to rule, he was essentially a kingdom-less King, confined to his dwellings, while Prince Regent Luitpold would rule in his stead until his death in December 1912 at 91. At that time, he was succeeded by his son Ludwig, first cousin to King Otto and King Ludwig II.

With King Otto still alive but unable to rule, he would die nearly four years later at the age of 68 due to a bowel obstruction, the Bavarian constitution was amended in 1913 to include a clause that allowed the Regency to depose the current King if they were incapacitated and unable to rule for 10 years or longer. As such, Regent Prince Ludwig would become King Ludwig III, the last King to rule through 1918 when the Monarchy was abolished due to WWI.

Contrary to some reports, work on Neuschwanstein Castle did not stop upon King Ludwig II’s death. Rather, portions of it had work continue for several years under modified plans, though most of the castle was, and remains, unfinished to this day (only 14 rooms are said to have been completed.)

Neuschwanstein Castle was ordered open to a paying public by Prince Regent Luitpold just seven weeks after King Ludwig II’s death. Despite the debt incurred by Ludwig II’s estate, its administrators could balance it by 1899 as the castles became lucrative tourist attractions. Ironically, King Ludwig’s expenditures on his castles have paid for themselves many times since Neuschwanstein Castle alone, drawing approximately 1.4 million visitors annually.

Art Inspiring Art, Inspiring Art

Aside from its unknown economic impact on the region, with over 1.4 million visitors annually, Neuschwanstein Castle continues to impact artistic inspiration. Just as it was inspired by the works of Richard Wagner and the imagination of a young king, Neuschwanstein Castle has inspired numerous other works of art. Perhaps the most recognizable and widely known influence is that of Walt Disney’s Sleeping Beauty Castle.

It’s almost fitting that the tragic life of a fantasy-loving King declared mad should inspire one of Disney’s most beloved fantasy tales that, in turn, continue to inspire others to this day.