Henry Evans Murdered Three In What Is Still Known As Slaughter Hill, Publicly Executed In Front Of Immense Crowd Near Court Street Bridge In 1828.

The public execution by hanging of Henry Evans in 1828 is notable for a number of reasons, first and foremost for being the first such execution in the history of Jefferson County. Secondly, the crime(s) for which he was executed have haunted the local geography for centuries via the name given to the area still used today: Slaughter Hill. There’s also the cast of characters involved in the trial, practically a “who’s who” of Jefferson County and Watertown settlers whose names are rich with history, folklore, and locations.

Lastly, the information from the newspapers over the years provided more information, some of it essential in that the research, rather than providing a bunch of information up front, came in pieces and decades later, which made it feel like revelations in a mystery. For this reason, the article will be presented more or less as they appeared in the newspapers chronologically.

The first such article found referencing the case of Henry Evans was from the May 16th, 1862 Daily News and Reformer—

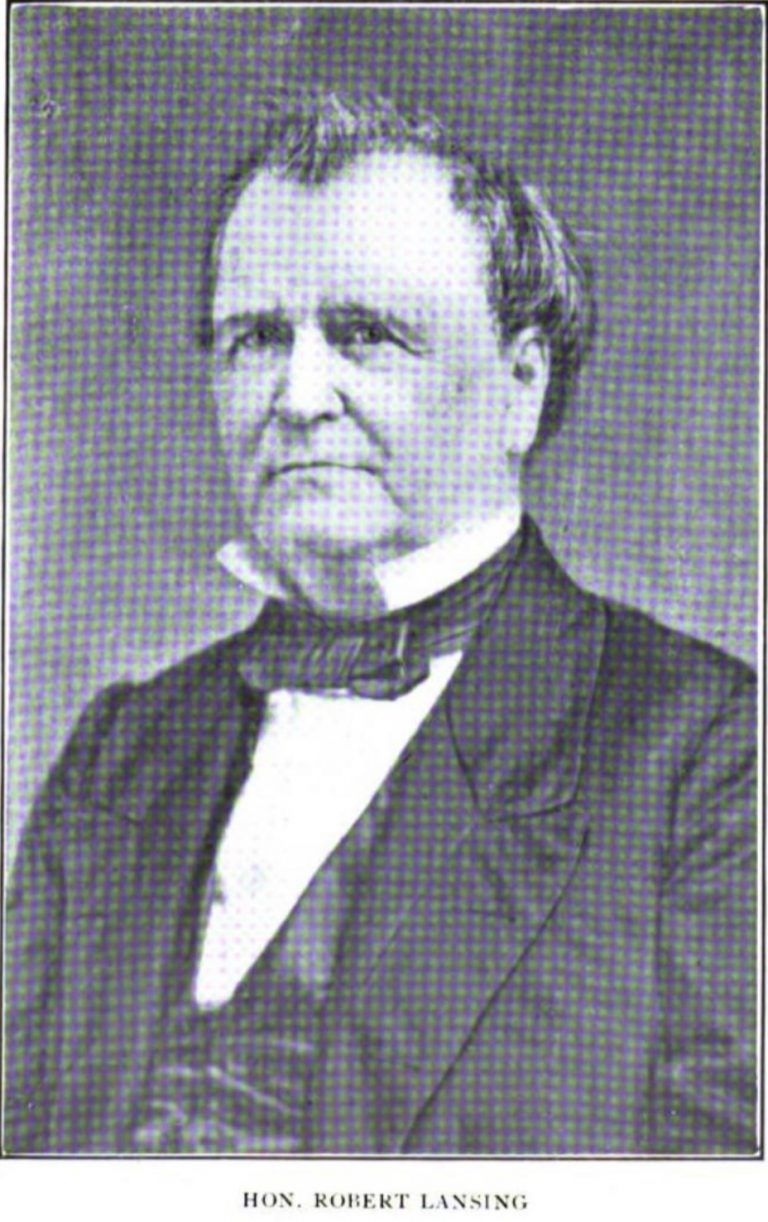

In 1828, at the June term of our circuit court, the well remembered murder case of Henry Evans of Brownville came on for trial—the court consisting of Nathan Williams circuit judge, Egbert Ten Eyck first judge, Joseph Hawkins associate judge, Robert Lansing district attorney, H. H. Sherwood clerk, and H. H. Coffeen sheriff.

Mr. Lansing was assisted in prosecution by C. E. Clarke, Esq., and the prisoner was defended by Mr. (Micah) Sterling, who was also assisted by his law partner, Isaac H. Bronson, and Nathan Rathbun, Esq., of Brownville.

It has been well said that “the vicious temper and abandoned character of the prisoner, who, whether drunk or sober, had been the terror of his neighborhood, outweighed the extenuating circumstances of the case and the jury, after half an hour’s deliberation returned a verdict of guilty.”

It is worth noting the accomplishments of some of the primary players:

Egbert Ten Eyck was later elected to represent New York’s 20th District in the United States House of Representatives; First President of the village of Watertown and the first judge in Jefferson County.

Robert Lansing is the grandfather of Robert Lansing, Secretary of State. The elder Lansing was, as noted, District Attorney and later elected to the New York State Senate and as county judge. He began his practice as a lawyer under Egbert Ten Eyck.

Henry Coffeen was County Clerk, elected to the New York State Assembly, publisher of the American Eagle newspaper in 1809, and elected Sheriff.

Charles Ezra Clark, a graduate of Yale and practiced law before being elected to the New York State Assembly and later U.S. Congress.

Micah Sterling represented New York’s 18th Congressional District and later the U.S. House of Representatives. Sterling’s home was the Sterling Mansion on his large estate. He was a good friend of Vice President John Calhoun, whom he named his son, John Calhoun Sterling, of Sterling Bookstore, after.

Bronson was a member of the U.S. Congress, New York Congressional representative, U.S. House of Representatives, and later served as Federal Judge for Florida’s eastern and northern districts.

On November 24, 1874, the Watertown Daily Times printed the second article, which strangely named two victims and not the third, ultimately leading to his death sentence. On a side note, one of the victims, Henry Diamond, often appears with the last name spelled “Dimond.” The article mentions the town was thronged with people but gives no estimate, which is provided in a later article. It also mentions the approximate location where the hanging took place.

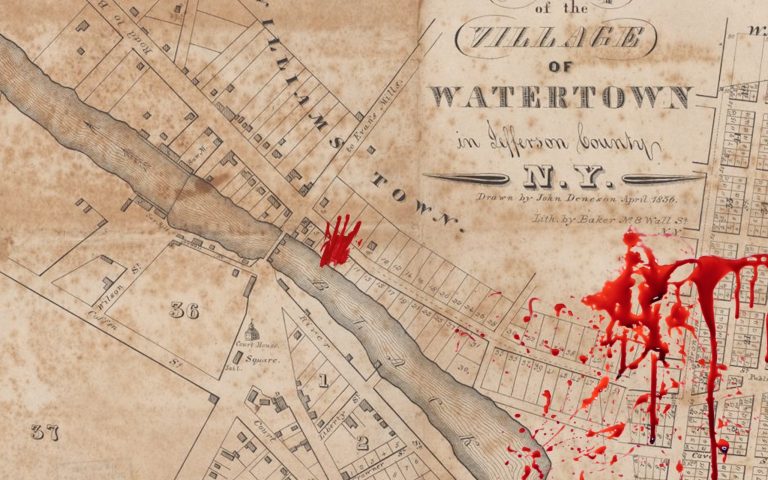

Forty-six years ago last August, the only man ever hung in this county, marched out from this place (county jail) to the gallows. Many of our oldest citizens remember all the circumstances and were eye witnesses to the scene. On a cross-road leading north from the road over the hill from Brownville to Perch River, may now be seen the ruins of an old house, where Henry Evans killed two men named (John/Joshua) Rogers and (Henry) Diamond.

Evans had possession of the farm where this old house stood, and Rogers and Diamond, claiming that he had no right to it, went there to dispossess him, and met their terrible fate; Evans following one into the road and literally chopping him to pieces with an ax. The room where Evans was confined, is what is now the dungeon, under the wing of the jail.

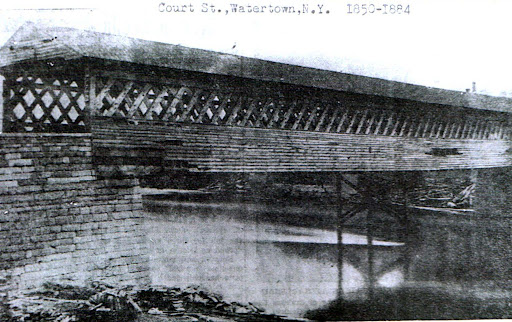

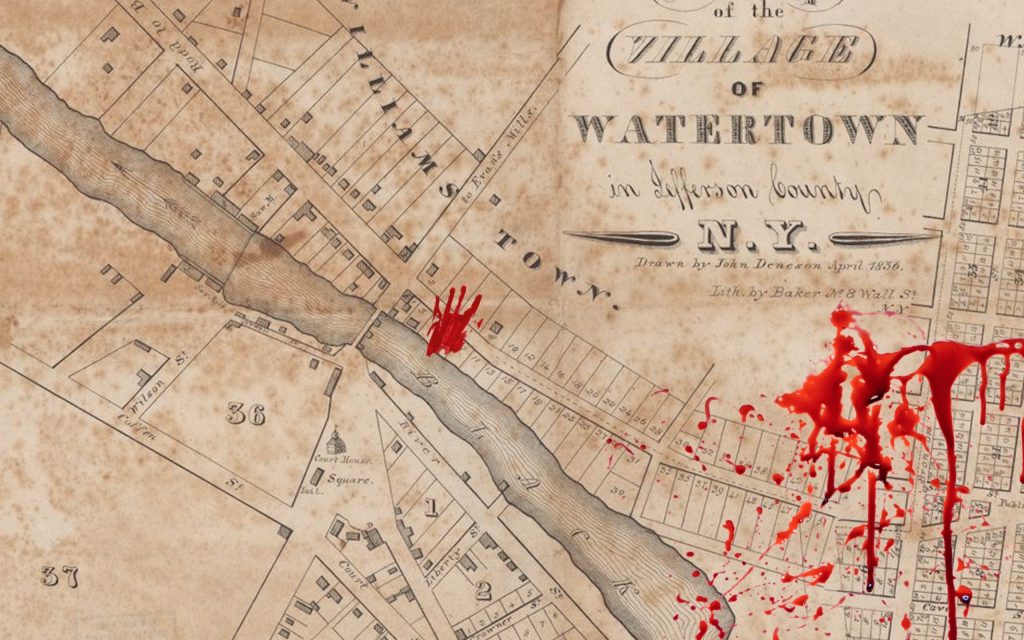

Upon the day of his execution the town was thronged with people. The militia and a company of calvary were ordered out, and at the appointed hour the prisoner was taken from his cell by the Sheriff, H. H. Coffeen. His coffin was placed upon an open platform wagon, and on foot behind, guarded on all sides, Evans marched across the bridge to the banks of the river, nearly opposite Arch-St.

The gallows stood on the land between the houses where John Challis and Michael Halloran now live; there were then no houses or streets in that locality, and the farm was owned by LeRay.A hollow square was formed by the cavalry, and Evans was soon launched into eternity in what was then the highest style of the art.

The third article, published July 2, 1892, in the Watertown Daily Times, provides even more specific information about where the gallows were erected. The article’s writer also notes their young age at the time, stating they did not witness the event itself.

The murder was prompted by an attempt to forcibly eject Evans from the premises occupied by him without legal process. Of the affair, all that is here proposed, is to speak of a few points not included in the record given in Hough’s history.

One of these is, as stated by the late T. T. Woodruff, to the effect that Evans having received an inkling of the premeditated attack upon the cabin, applied for legal counsel to Lawyer Rathbun, of Brownville, whose reply to Evan’s inquiry what to do in case of attack, was “kill them, damn them, kill them.” The sheriff, upon whom devolved the execution of Evans, was Henry H. Coffeen. It was currently reported that he had no little difficulty deciding upon the best point to erect the gallows where the largest possible number might witness the revolting spectacle. It was finally revealed to him in a dream.

The spot was nearly due north of the jail, on the opposite side of the river, and, as the writer is able to locate it, just east of LeRay Street, on Lynde Street, and not far from the spot now occupied by Hose Company No. 4 (on Curtis Street.) The execution was witnessed by a great concourse of men, women and children, not alone from Jefferson, but from adjacent counties.

The writer, then eleven years old, did not witness the execution, and does not regret it. Going in the morning, to visit a menagerie, which was exhibited on Court Street, on a vacant lot, nearly opposite where the Kirby house now stands, he remained there until after the affair was over, while all the other visitors at the show left, and the men in charge climbed up on the poles which supported the canvass enclosing the show, to obtain a view of the spectacle.

Going again the following day to the same show, the writer distinctly remembers seeing Sheriff Coffeen there dressed, in the fashion of the day, in swallow-tail blue broadcloth coat, with brass buttons, white linen pants and stove-pipe beaver hat.

All of the preceding reports failed to mention some important details of the murder. These were published by The Times on October 4, 1897 when a reporter found a leather-bound book in the county clerk’s office from the trial—

The book contained the record of the proceedings of the term of the court of Oyer and Terminer held in this city June 16, 1838 (sic), at which Henry Evans, of the town of Pamelia, was tried for murder in killing an officer who tried to evict Evans from his farm.

The eviction was attempted in the night by two of Evans’ brothers-in-law and a constable. Evans resisted and killed his two brothers-in-law with an ax on the farm. He chased the constable off the premises and killed him. Evans was exonerated from the charge of murder in killing his brothers-in-law, but found guilty in killing the constable.

The outcome of the trial is clearly indicated by the following order, which is taken verbatim from the court record:

“The jury having returned a verdict of guilty in this cause, ordered, on motion of R. Lansing, Esq., district attorney, that the prisoner, Henry Evans, be taken hence to the prison from whence he came and from thence to some fit and proper place within this county for execution and there on the 22d day of August next, between the hours of 12 at noon and 2 in the afternoon be hung by neck until he is dead.”

The vacant lot at the corner of Main and LeRay street, where the residence of D. A. Wait now stands was selected as a “fit and proper place” for the execution, and there at the appointed time, in the presence of a curious crowd, Evans expiated his crime with his life. He was the first man ever executed in Jefferson county.

The question of how many people attended the execution of Henry Evans will never be known. Still, an article in the October 27, 1923, Watertown Daily Times stated, “According to the papers of the time about half the population of the county, 20,000 people, were on hand to witness the hanging.” An editor at the time counted over 500 wagons present, and, as noted previously, people came from neighboring counties.

Of interest is the conflicting report from other sources that stated the third person attacked had recovered. Here, he’s referenced as being a constable. Micah Sterling got the charges for the murder of both Rogers and Diamond reduced to manslaughter, but Evans couldn’t escape the fate of having killed a constable. The name “Joshua Rogers,” not John Rogers, was also used around this time. Many years later (1937), it came to light that Henry Evans was, in fact, one of the heroes of the Battle of Sackets Harbor during the War of 1812.

Another article from January 29, 1940, detailing some of the history of Perch River noted—

Tradition has it that Evans’ body was buried secretly at night in an unmarked grave somewhere a short distance north of Perch River, as permission could not be obtained to inter it in any of the nearby cemeteries.

With such a long-ago and lurid crime and punishment at hand, it’s not hard to believe some of the tales that have sprung forth as history gets colored with time and imagination. An October 25, 2010, Times article regarding a walking tour for Halloween noted—

According the legend, Henry Evans murdered three friends and his arresting officer with an axe. Mr. Evans was sentenced to “hang by his neck until dead.”

Mr. Evans was buried in Brownville, but after townspeople reported seeing his ghost, they demanded that Mr. Evans’s bones be dug up and relocated in the city of Watertown.

He did not rest in peace there, the legend goes. City residents reported seeing a vampire resembling Mr. Evans and they, too, ordered his remains moved. His remains lie somewhere outside the city in an unmarked grave.

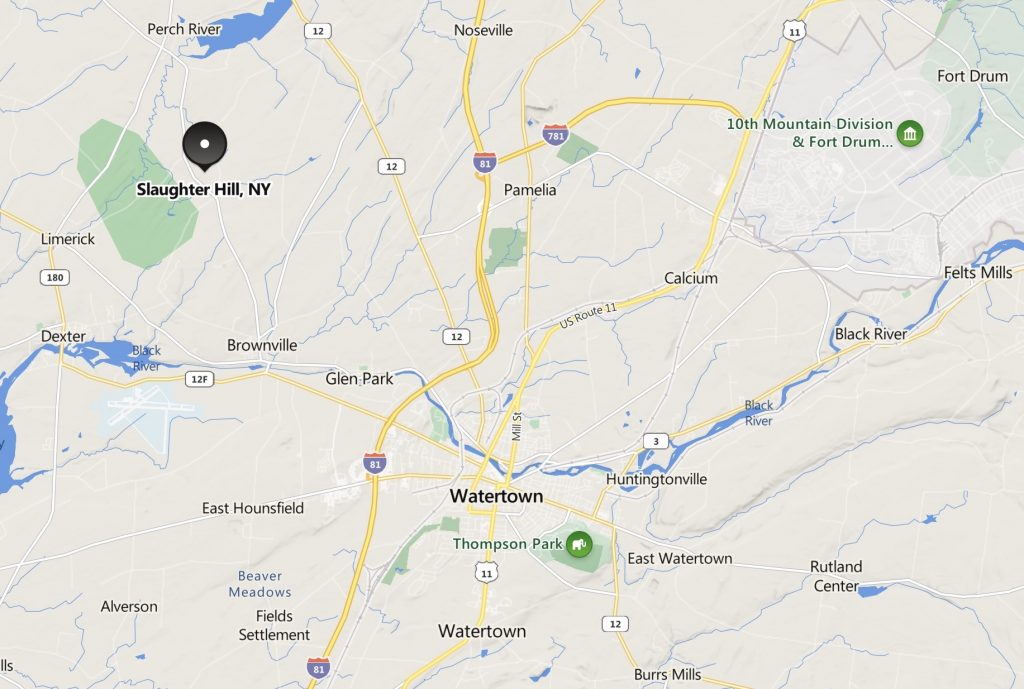

Slaughter Hill

Slaughter Hill is one of those names most likely established by locals and never formalized to any extent. In 1888, the Watertown Daily Times published a (very) short blurb about Slaughter Hill’s location, having published articles occasionally about the area. This confused readers unfamiliar with the name or the area, so the Times noted, “It is situated between the villages of Brownville and Perch River.”

The location of the Evans home is unknown and is undoubtedly long gone as we inch closer to the events that took place two full centuries ago. Still, the location of Slaughter Hill itself is searchable and shows up on most internet map engines.

A Recollection, Printed in 1905

The following is taken from the fascinating column “Recollections of Watertown by a School Girl of Three-Quarters of a Century Ago by Mrs. Wayne Clark, Copenhagen, Feb. 12, 1905. The series details a number of very interesting tidbits about life dating back to the early 1820s.

“In eighteen hundred twenty-one or two, my father, L. W. Clark, an architect and builder, just past his majority, located in Watertown, N.Y. Their first home was on lower Court Street, in view of the public hangings of Evans, and I remember hearing my mother tell of drawing the curtains to shut out the sickening sight.