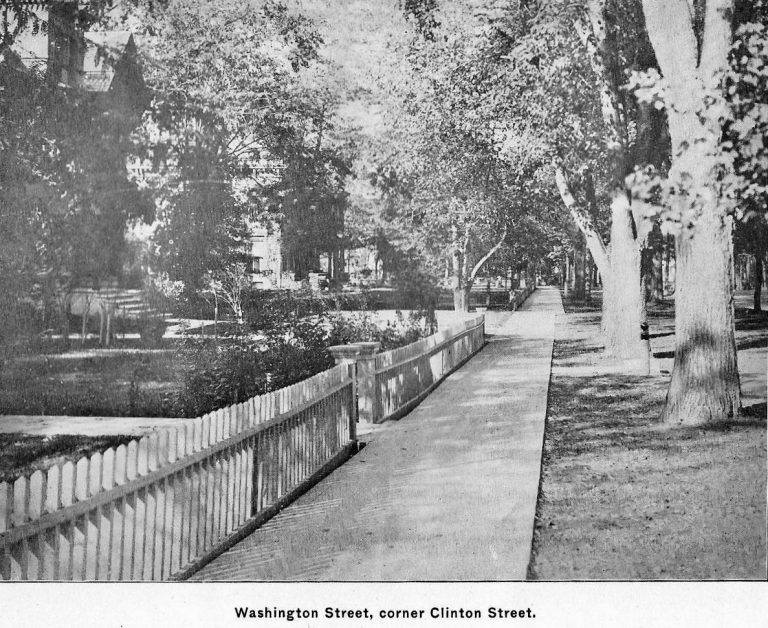

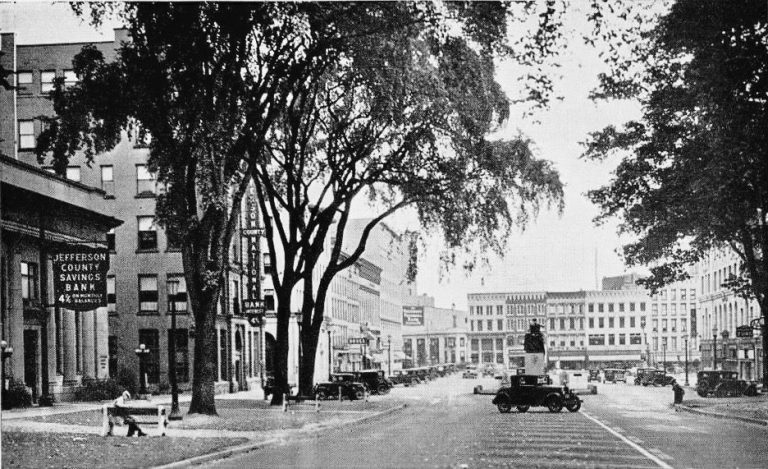

The Dutch Elm Disease Forever Changed the Landscape of Washington Street

Ice Storms and a microburst. Neither have had a more lasting impact on the landscape than the Dutch elm disease that spread like wildfire throughout not just Watertown, but most of North America, Europe and New Zealand. First reported in the United States in 1928 and New York State a few years later, it would take a few decades for it to hit locally though the warnings were sounded well in advance. According to the New York Times, of the estimated 77 million elm trees in North America in 1930, over 75% had been lost by 1989.

On September 11, 1947, the Watertown Daily Times would note trees being a community responsibility–

Watertown owes much of its standing as a beautiful city to its many trees, and whatever can be done to preserve our elms from the Dutch elm disease, from the elm beetle, and keep our maples, beeches and birches in good health all contributes to the future appearance of this community. Replacements of storm or age-wrecked trees also has a sympathetic interest of intelligent men and woman.

Eight years later, eight trees were discovered infected by the Dutch elm disease and advised to be destroyed by city manager C. Leland Wood. Once infected, there’s no chance for the tree to recover.

The Dutch elm disease is spread when hundreds of eggs are hatched and the young beetles carry the deadly spores, often heading to the top portion of trees where the bark is newer and thus softer. As they feed on the tender bark, they leave behind the spores that infect the elm trees, causing a brown, gum-like substance that clogs the tree’s circulation and causing it to die as a result.

In 1956, Federal agricultural inspectors reported that the Dutch elm disease had nearly tripled in Watertown. The concerns with Mayor William J. Lachenauer and the city council were very apparent, but what action to take wasn’t.

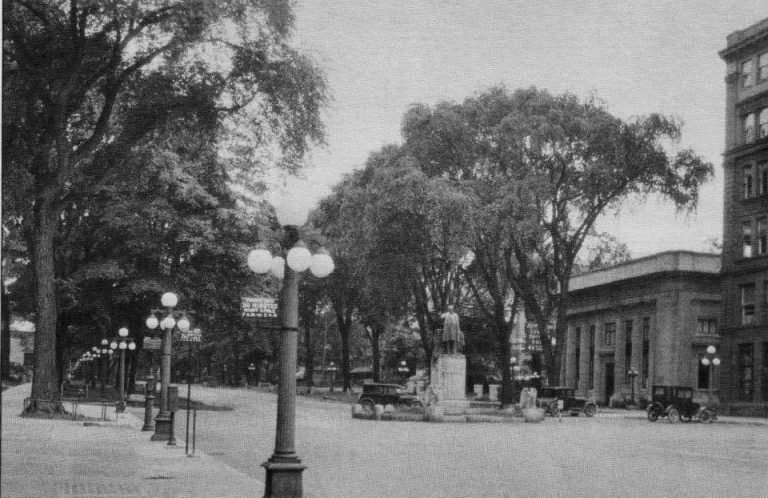

A letter to the Mayor from visiting Rev. Forest J. Campbell, who just completed a 2,000 mile car trip with his wife from West Virginia, though very complementary, unintentionally noted what was at stake–

“Watertown impressed us as the most beautiful city we visited,” said the minister. This city’s vast array of trees lining residential streets were more impressive to the West Virginia visitors than the scenic falls at Niagara Falls, the minister said.

“The visit to your city added much to our trip,” he added.

By the mid-1960s, more than 25 million elm trees died in the United Kingdom alone. France would lose 97% of its elms during the time period as well. With infections spreading at an alarming rate throughout New York into the early 1960s, the city of Watertown would begin trying to prevent further damage by the Dutch elm disease by systematically spraying the city’s wards.

In 1967, the city would offer a program to have individual trees on private properties sprayed for $3 apiece. The August 12 Watertown Daily Times reported–

City’s Majestic Elm Trees In Danger; 400 More Are Dead

Unless science comes up with a solution very soon, Watertown’s elm trees will be little more than a memory.

Since pioneer times, these elms have majestically shaded city streets and residents have taken them for granted.

But now Dutch elm disease has its foot in the door and is killing off these shade trees by the hundreds.

This summer alone no less than 400 of them have died and are in the process of being cut down and burned, according to City Manager Ronald G. Forbes. The worst part about it they are not being replaced.

Mr. Forbes said it costs from $300 to $500 to cut down a single tree. “It is up to the owners to replace them,” he noted, since most of the trees were on private property.

The following year, the Watertown Daily Times reported that the city had removed an estimated 1,300 elms in the last decade starting in 1958 and feared all may be gone within another. Despite spraying the trees annually, the pace of infections had increased and necessitated two public works crews working full-time to cut infected trees.

By 1970, there were still approximately 2,500 elm trees left in the city that were more or less declared doomed with 200 scheduled to be removed. A year later saw 60,000 diseased elm trees cut down along a 120-mile segment of the 401 near Kingston, Ontario.

Making matters worse, another lethal disease, elm phloem necrosis (EPN for short), invaded New York in 1971 according to a Cornell University plant disease specialist. The white-banded American leafhopper acted as the carrier for the submicroscopic organism “mycoplasma” which causes the root disease. Much like the Dutch elm disease, once a tree is infected, it cannot be cured.

As the 70s went from bell bottoms to corduroys, the count of tree-cutting continued to thin out Washington Street. 1973 would see about 300 diseased trees taken down. In 1974, the Department of Public Works were still cutting down dead elm trees reported to the city in 1971 with numbers steadily increasing every year.

1975 saw the biggest elm tree in Jefferson or Lewis County fall victim to the disease. Approximately 144 years of age, the tree, located on the Brownville-Airport Rd. (route 12F) measured 14 feet, 11 inches in circumference and was 98 feet tall with an average crown spread of 98 feet – at the time measurements were last taken in 1972.

By the late 1970s, much of the city’s majestic elm trees had been lost with the vast majority of the damage done in the 60s and 70s. Lignasan BLP, a fungicide, would be introduced in the 70s and used by injection into the base of the tree. It ultimately proved to have little effect, but Arbotect, introduced several years later, has been proven more effective with regular injections about three years apart.

In recent years, scientists have been able to produce hybrids known as “cultivars” that have been proven to effectively resist the Dutch elm disease. In the most recent 10-year study of American cultivars that ended in 2015, it was found that the preferred cultivars of American elms were named “New Harmony,” and “Princeton” – giving hope to elm trees once again gracing our streets someday.

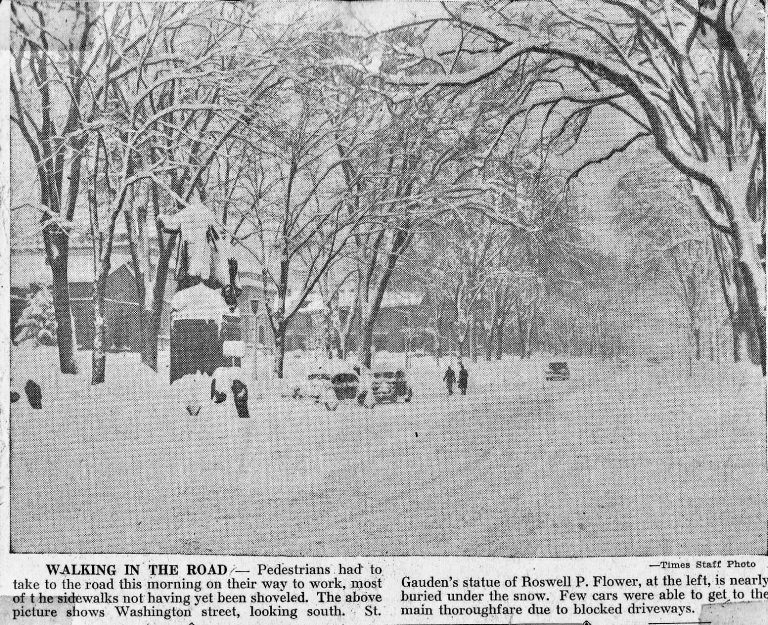

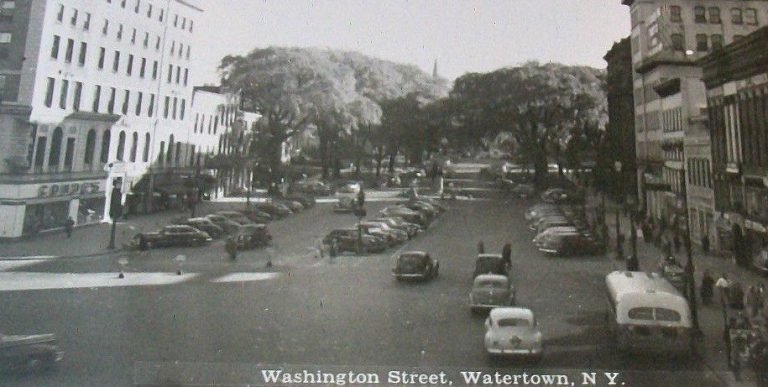

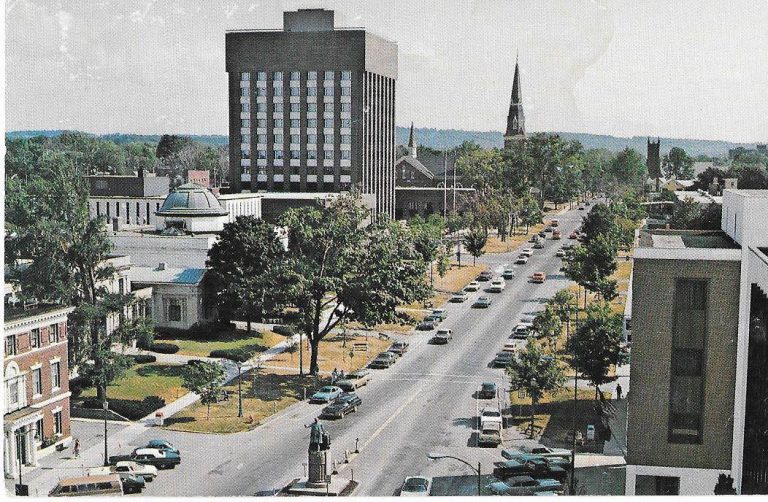

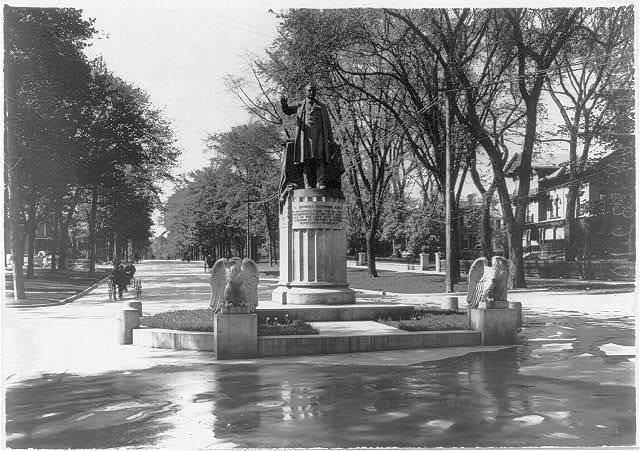

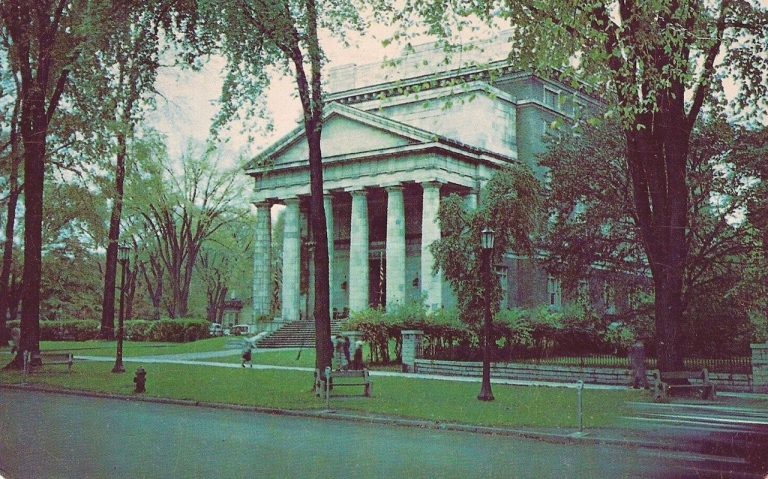

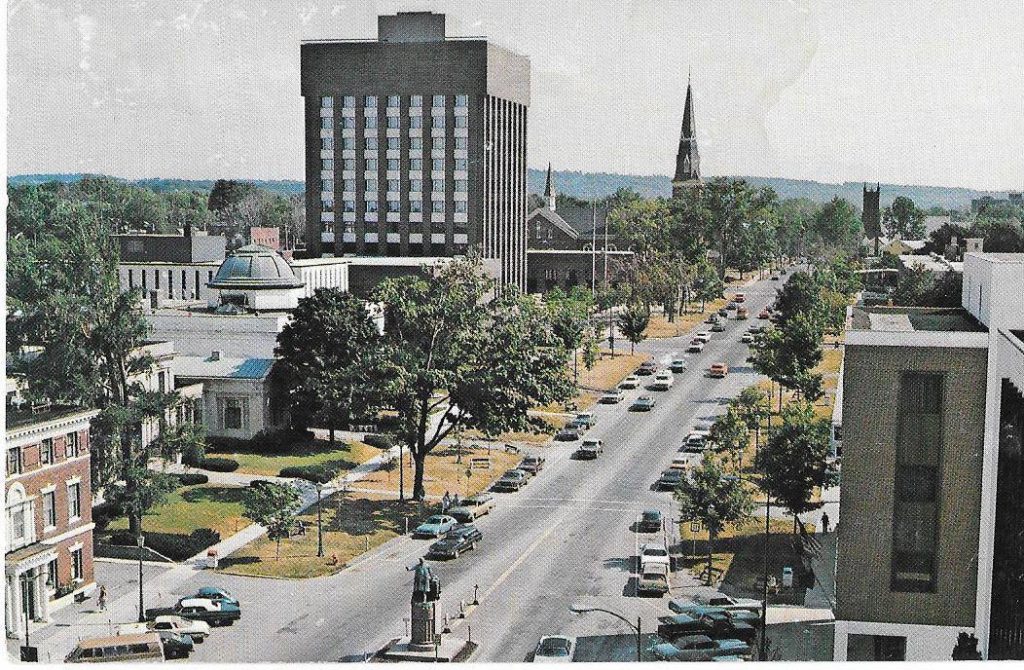

Washington street as it looked in 1976, after many of the trees were lost to Dutch elm disease. The Roswell P. Flower Memorial Library clearly visible here where just three decades previous, it would be hidden amongst a canopy of trees. Photo: unknown credit.

Washington street as it looked in 1976, after many of the trees were lost to Dutch elm disease. The Roswell P. Flower Memorial Library clearly visible here where just three decades previous, it would be hidden amongst a canopy of trees. Photo: unknown credit.