Henry Keep and the Keep Mausoleum in Brookside Cemetery

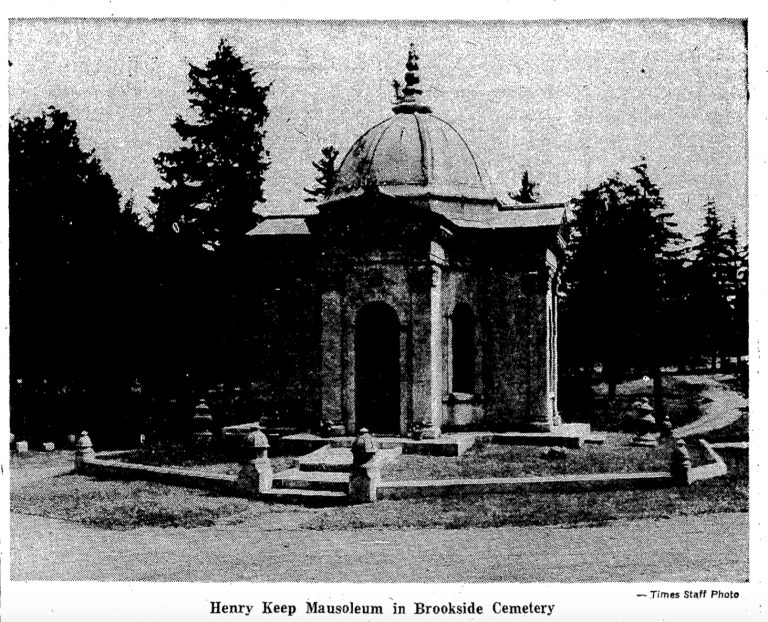

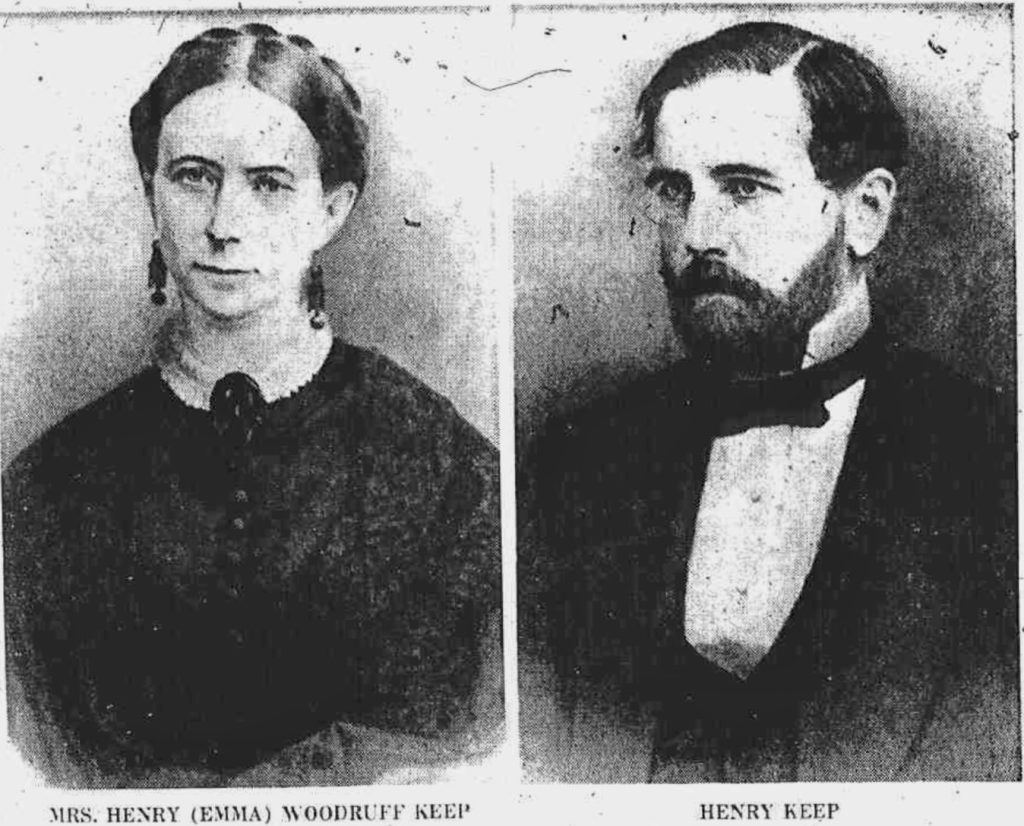

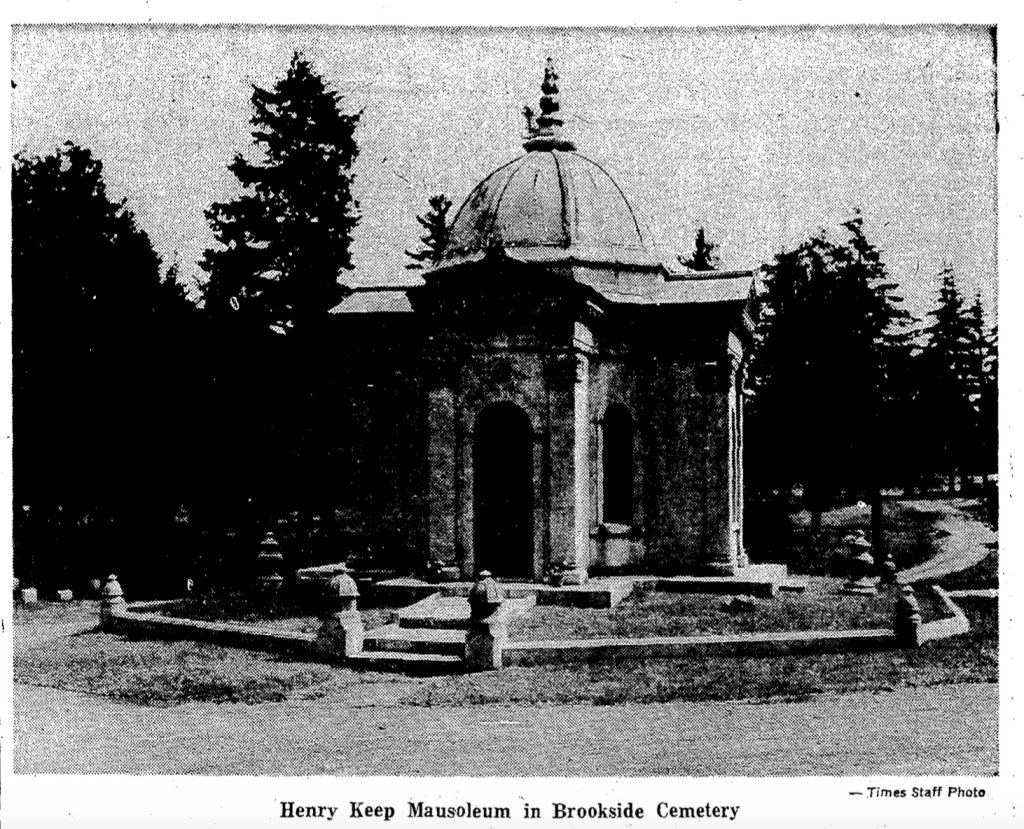

The Keep Mausoleum in Brookside Cemetery was built as a monument to the railroad magnate and Wall Street financier by his widow, Emma Woodruff Keep. She purchased the lot for $283.70 shortly after Henry Keep‘s death on July 30, 1869, and construction began the same year. Though the mausoleum would cost $70,000, over $1.6 million in 2024 currency value, and take three years to complete before the public could visit in 1872, it also serves as a testament to the rags-to-riches story of Keep’s humble beginnings.

Born in 1818 in Adams, N.Y., to Herman and Dorothy Keep, Henry Keep and his family lived in poverty, with Dorthy passing away in June 1831, less than a week before Henry turned thirteen. The Jefferson County Poorhouse opened its doors the following year, thanks partly to benefactor Orville Hungerford, and Herman and Henry (and his siblings, too) lived there until Herman died in 1835. At seventeen, Henry found himself bound out to a local farmer, Joseph Grammon, where his harsh treatment of beatings, neglect, and the want for a better life had him running away to the Rochester area with a “two-cent reward” offered for his return.

Keep soon found work on the Erie Canal and other jobs and saved his money, waiting for the opportunity to invest. One day, he learned that Watertown, Sackets Harbor, and Adam Banks issued banknotes were worth much less in the Rochester area. Buying as many discounted notes as possible, he returned to the Watertown area and sold them for their total value. While there, he discovered the same conditions existed with Canadian currency floating about New York state.

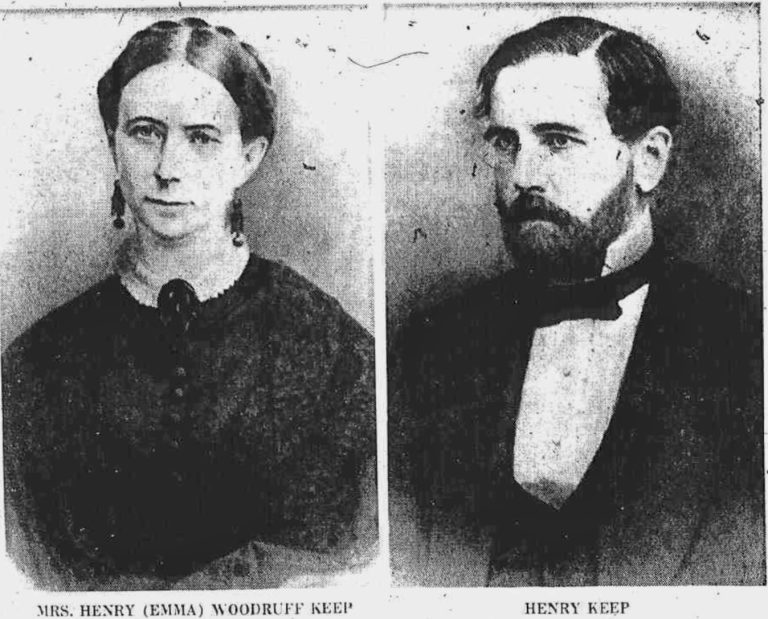

He soon accumulated Canadian notes in trunks and boxes, crossed the border, and sold them at par. By age 29, Keep had amassed enough wealth to open his eponymously named bank in Watertown. Citizens and Frontier Banks followed, each moving to other locations (Citizens to Ogdensburg, then Fulton; Frontier to Potsdam). During this period, he married Emma Woodruff, the eldest daughter of Norris Woodruff of the Woodruff House, rebuilt after the great fire by architect Otis Wheelock, who was responsible for many of Watertown’s buildings of the rebuilding era.

After opening the banks, Henry and Emma moved to New York City, where he became involved with Wall Street and railroad stocks. The first railroad Keep became directly affiliated with was the Michigan Southern & Northern Indiana Company, with which he became treasurer in 1861. According to a Watertown Daily Times article published on August 1, 1969–

Henry Keep wasn’t the only financier who wanted to control M.S. & N.I. A man named Addison G. Jerome foresaw that the M.S. & N.I. would be a part of the future unified New York-Chicago line and began to buy its stock.

For Henry Keep, silence was gold and not merely golden. By his financial reticence he earned the name of “William the Silent” on Wall Street, and his dealings with the M.S. & N.I. demonstrated how dangerous and profitable his silence could be.

Just when Jerome thought he had bought all the stock of M.S. & N.I. there was to buy, his messenger boys started bringing in more shares, none of which he refused to buy.

Jerome didn’t know that Keep had issued 15,000 shares of stock under the radar, raising the company’s value from nine to 10.5 million dollars and selling most of the stock to Jerome. In September of 1863, the stock began to depreciate, but Jerome kept his eye still on the prize, eventually having to sell at a “disastrous loss.” Later, Keep positioned the New York Central, but Cornelius Vanderbilt held the Hudson River Railroad, wanting to extend it across New York state.

Vanderbilt won an agreement for his line to transfer New York Central’s freight to New York City, which also required a $100,000 bonus. This resulted in Keep amassing a majority of stock with other prominent shareholders, and New York Central elected him its president.

Shortly after that, the $100,000 yearly bonus was revoked, and Vanderbilt countered by shutting off service from East Albany. This forced the New York Central to concede to the Hudson River Railroad for passage to New York during the winter, leaving the New York Central unable to move cargo as its shares dropped. Vanderbilt and the Hudson River Railroad had won the battle, but Henry Keep received the spoils, selling 35,000 shares to Vanderbilt for a massive profit. Unfortunately, Keep dabbled only briefly with various railroads before he became sick.

Henry Keep, 51, died in 1869 from an unspecified “incurable disease,” according to John A. Haddock‘s Growth of a Century. At that time, he had amassed a fortune between $4,000,000 and $5,000,000 ($92 million and $116 million in 2024 currency value). Roswell P. Flower, Keep’s brother-in-law via his marriage to Sarah Woodruff, moved to New York City upon administering Keep’s estate and became involved with Wall Street. Henry was temporarily interred in the Hungerford Mausoleum while construction on the Keep Mausoleum took place across from it, and Emma commissioned an old family friend to build it.

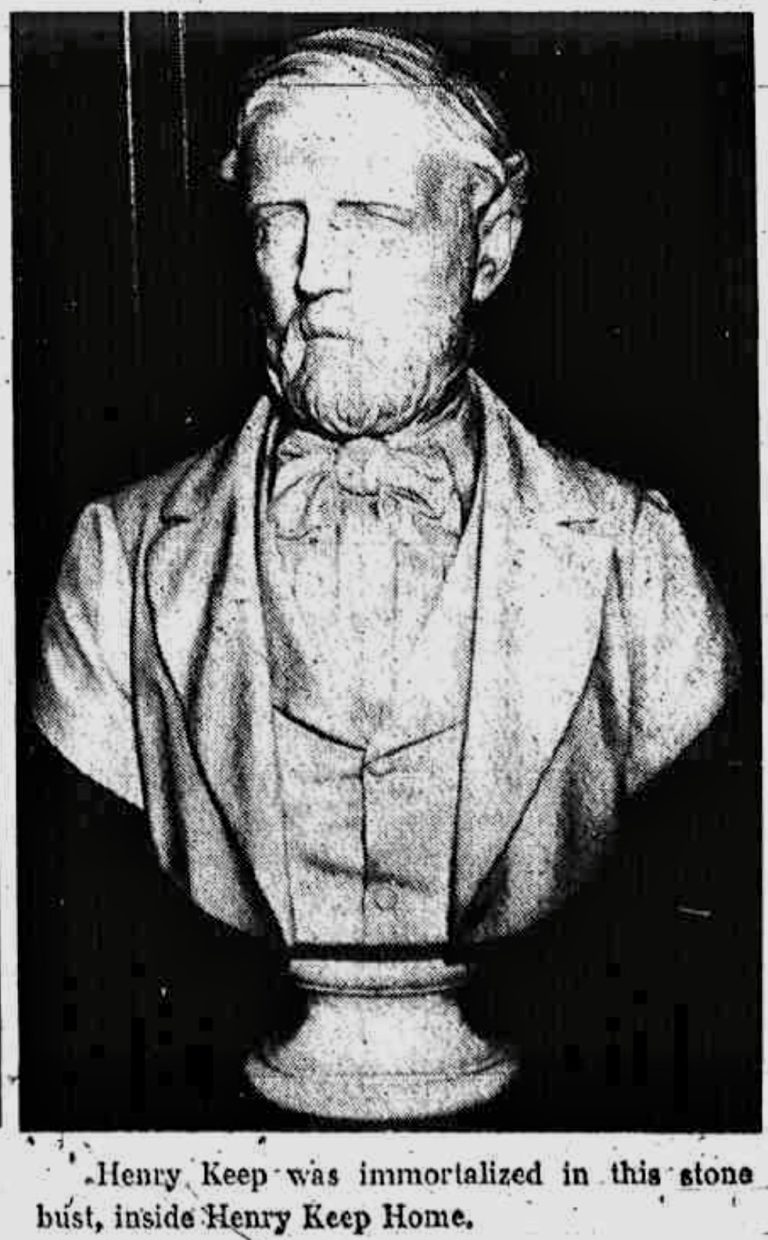

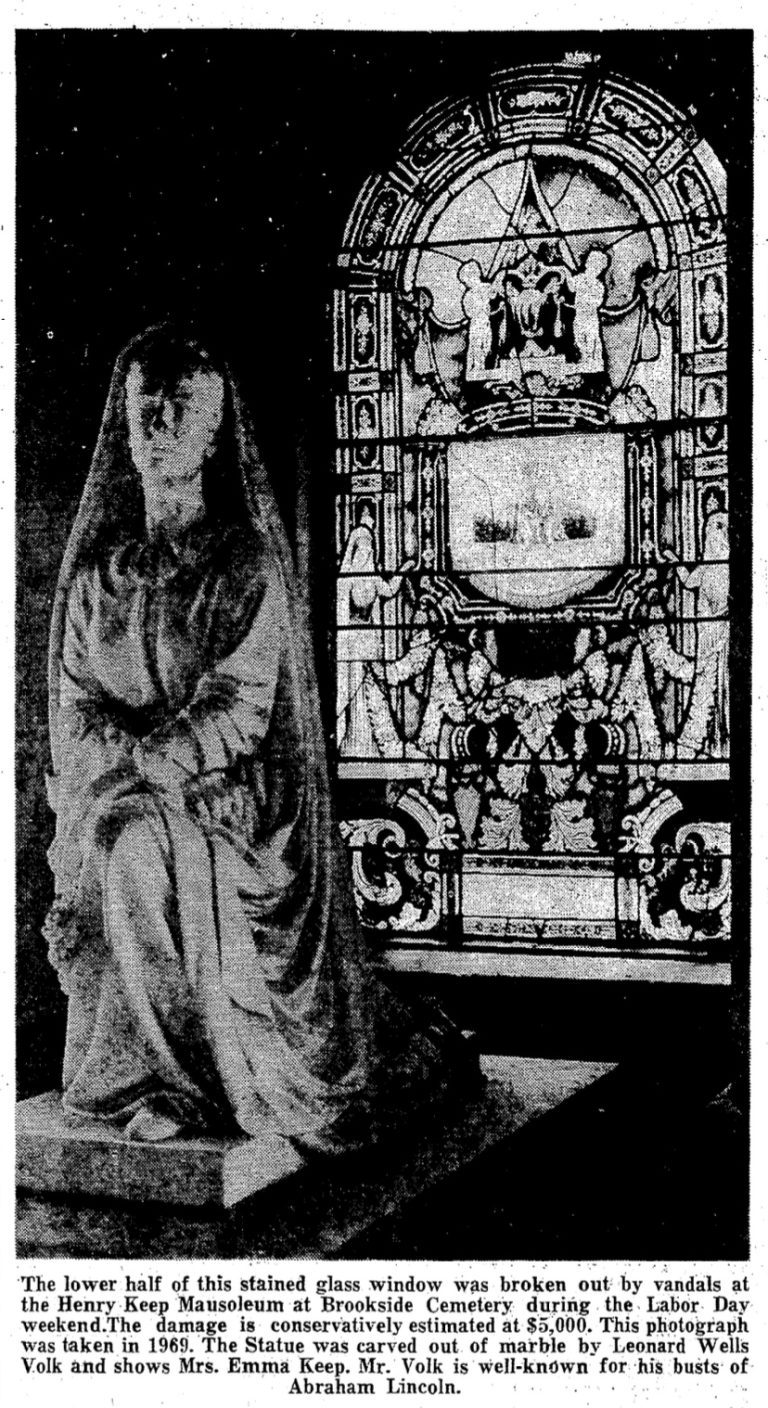

Otis Wheelock had since removed himself to Chicago but returned to Watertown and designed the $70,000 mausoleum. Designed after a Greek cross, the Keep Mausoleum would take three years to complete and involved the works of Leonard Wells Volk, who finished the statues of Emma Keep and her and Henry’s only child, daughter Emma Gertrude Keep. A bust of Henry was also done. Volk was a world-renowned sculptor born in Wellstown (then known as Wells), Hamilton County, New York. He studied in Rome and is best known for his works of Abraham Lincoln.

One hundred years after his death, Watertown Daily Times reporter Martha E. Bellinger wrote of the mausoleum in an August 1, 1969 article–

The Keep tomb is undoubtedly one of the most elaborate mausoleums in the north country and could easily rival the Vanderbilt tomb on Riverside Drive, New York City. It is doubtful, however, that Keep would have wanted the rivalry between Vanderbilt and himself to have followed his tracks into the grave.

Unfortunately, as elaborate as the tomb is, the Keep Mausoleum has been plagued with issues from early on that, to this day, threaten its future. Six years after it opened in 1872, it required a thorough overhaul due to frost damage caused by temperature differentials between the interior and exterior. The large stained glass was found broken, with “considerable damage otherwise.” The Watertown Daily Times reported of the work to be done on June 9, 1878–

New plate glass with monograms and representations similar to those on the old glass have been ordered from Europe and are expected in a few days. A gentleman from Quincy, Mass., will arrive in the city to-morrow for the purpose of beginning the work of improvement. He will be assisted by Patrick Phillips, who will have charge of the help.

The mausoleum will hereafter be ventilated by tubes, and it is thought that when this is accomplished, the frost can do no damage.

The following year, the Watertown Daily Times reported vandalism at both the Keep and Hungerford mausoleums in their September 7, 1874 edition—

Some vandals have smeared the Keep Mausoleum with coal tar. The steps, window sills, and all the windows, save one, are daubed with the foul compound. The Hungerford tomb has the mark of a cross on upon its door, made with the same article. The offense is outrageous. If the police do not detect the perpetrators, let the friends of the deceased offer a thousand dollars reward and make the detection and punishment of the rascals sure.

In 1909, it was reported that the vandalism was subsequently “found to be an act of an insane man.” Another issue plagued the Keep Mausoleum in 1874 was its granite roof, which proved defective due to leaks. After unsuccessful attempts to repair it by parties from Chicago and New York, Patrick Phillips was again called upon and given authority to repair it by Emma Keep.

Having remarried in 1874 to Judge William Schley, who later had Schley Drive named after him despite never residing here, Emma Keep-Schley paid for the expenses and sent Phillips a $10/day gift for the work, amounting to $730. After eight years of marriage, Judge Schley died in 1882 and was interred in the Keep Mausoleum’s basement.

By this time, the construction of Emma Keep-Schley’s other monument to Henry was nearing completion: The Henry Keep Home for the Aged. Roswell P. Flower was later quoted in the New York Red Book, published in 1896, as saying, “What better use could be made of the money of Henry Keep, whose father died in a poor-house, than to erect, with some of it, a home for aged men and women.” Excavation began in 1881, with Patrick Phillips again providing construction oversight with the masonry work. Upon its opening in 1883, Roswell P. Flower stated–

It has been regularly incorporated under laws of the State of New York as an Eleemosynary Institution, and, with its 35 acres of ground suitable for garden purposes, and its annual income, it will stand, I trust, forever a blessing to the county, a monument to the charity and loving kindness of Henry Keep, and his wife, Emma Keep-Schley, and refuge, for many generations, of indigent but worthy persons in time of trouble.

In 1890, the Keep Mausoleum installed two-and-a-half-ton bronze doors, which were completed by Baker Manufacturing Co., located on Newell Street. Their Boston designer stated, “The casting could not be better done anywhere in the country.”

Emma Keep-Schley would join her husbands in the hereafter in 1900 after passing away in her Manhattan home. Her estate was valued at $10,000,000, or $375,358,333.33 in 2024 currency. Most of it would go to her only child, Emma. $40,000, $1.5 million in 2024 currency, was placed into a trust to pay for the maintenance of the Keep Mausoleum, with only the use of the interest as payment. Another benefactor of Emma Keep-Schley’s fortune would be Helen Mundy Van Brunt of Watertown, her niece, who then used a portion of the $500,000 to build the Van Brunt mansion on Washington Street, better known in later years as The White House Inn.

The only child of Emma Keep-Schley and Henry Keep, Mrs. Emma Gertrude Keep Halsey, wife of General Frederic Robert Halsey, died in 1908 in her New York City home. Emma was the older cousin to Emma Gertrude Flower Taylor, who was undoubtedly named in honor of her. Emma Flower Taylor would return the honor by naming her second child with John Byron “Jack” Taylor, Frederic Halsey Taylor, after Emma Halsey’s husband. After death in 1918, Frederic Robert Halsey was interred in the Keep Mausoleum, joining Judge William Schey in the crypt’s basement. The couple had no children, thus ending any further direct descendants of Henry and Emma Keep.

As the Great Depression entered its second year in 1930, the Keep Mausoleum underwent another $1,101.46 of unspecified repairs. Years later, in a 1973 article, The Watertown Daily Times mentioned Emma Flower Taylor, who stated in a book she wrote about her father that the Keep Mausoleum was rebuilt in the early 1920s because the original structure was built on quicksand. However, no mention of the work could be found in the newspaper archives.

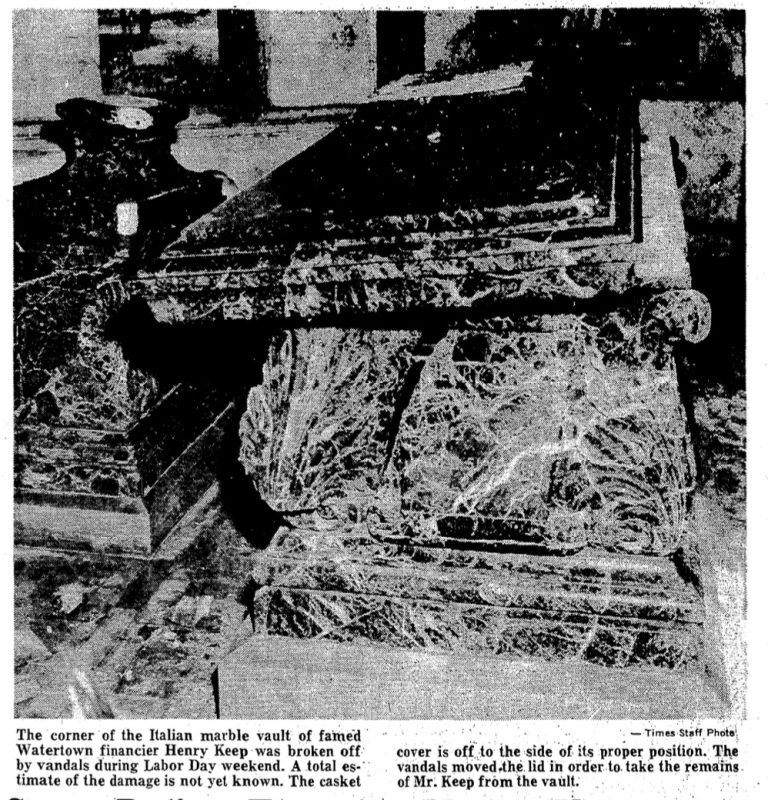

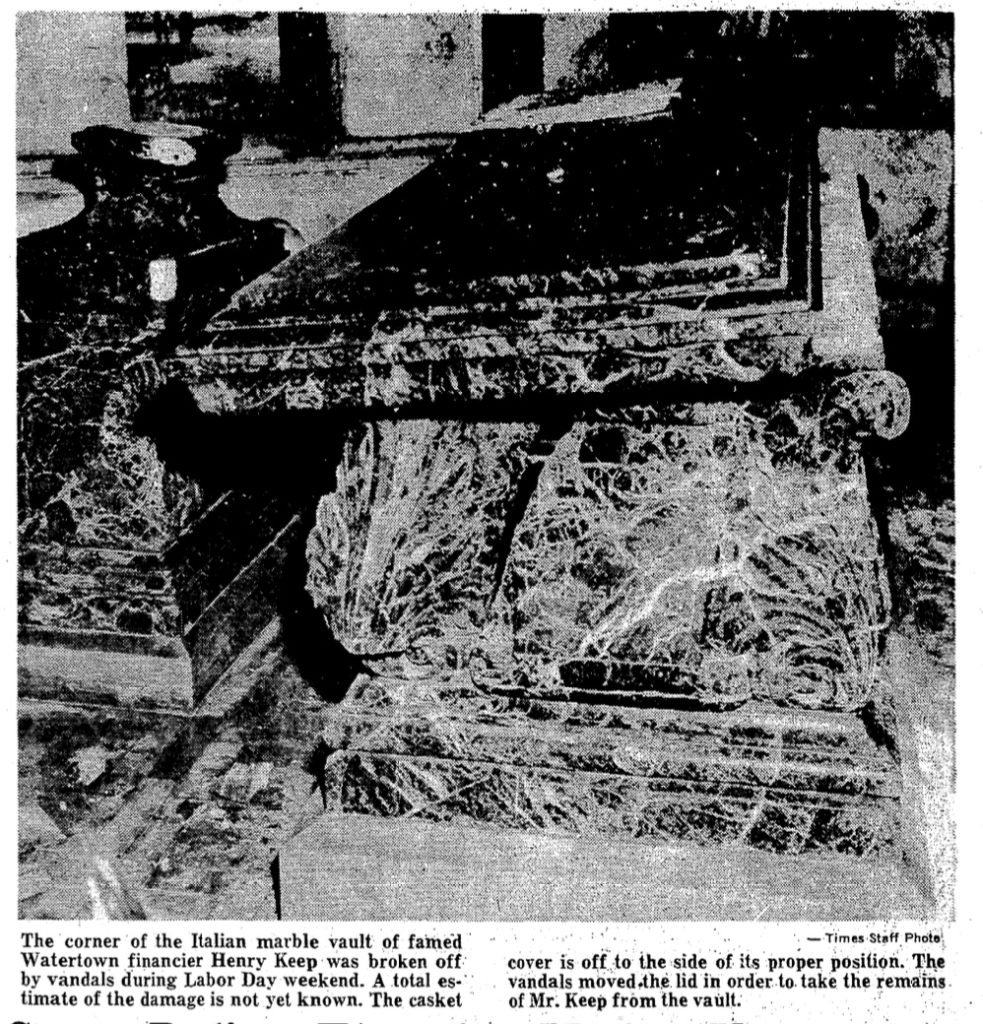

Perhaps the costliest work performed on the tomb resulted from an act of desecration in 1973. Over the Labor Day weekend, vandals broke the bottom of the stained glass window to gain entry into the mausoleum. Inside, the damage continued as they chiseled Keep’s Italian marble vault and strewed his remains about in what authorities could only theorize was a search for valuables buried within. The cost of the stained glass window alone was reportedly over $5,000. It was later reported in a Times article on June 27, 2004–

After the 1973 break-in, “I know the cemetery spent an awful lot of money on repairs – over $40,000,” said former Brookside Cemetery superintendent Maurice L. Herron. “Plus when they did the repairs, they did a lot more work in the mausoleum that needed to be done.”

The Keep Mausoleum had another round of repairs sometime after 1985 when Charles R. Hyde was Executive Director of Brookside Cemetery. However, details of what was explicitly done and the associated costs could not be found.

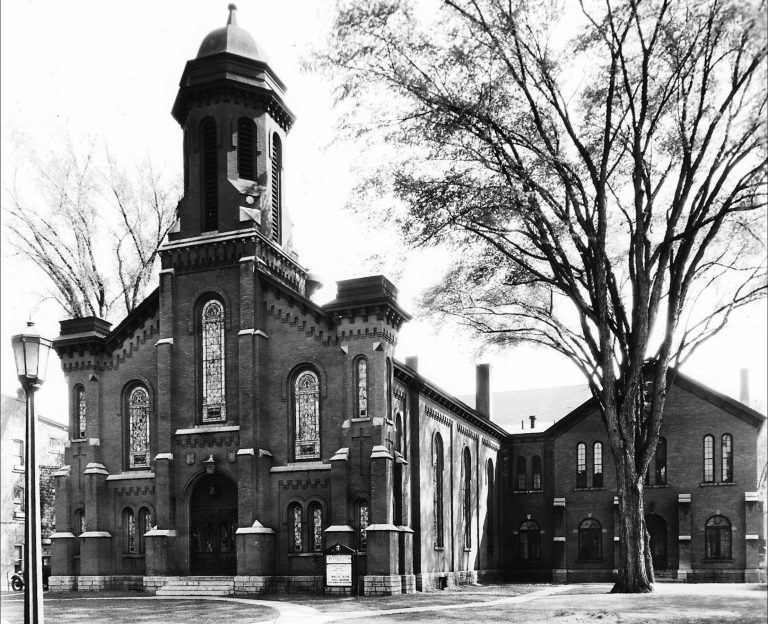

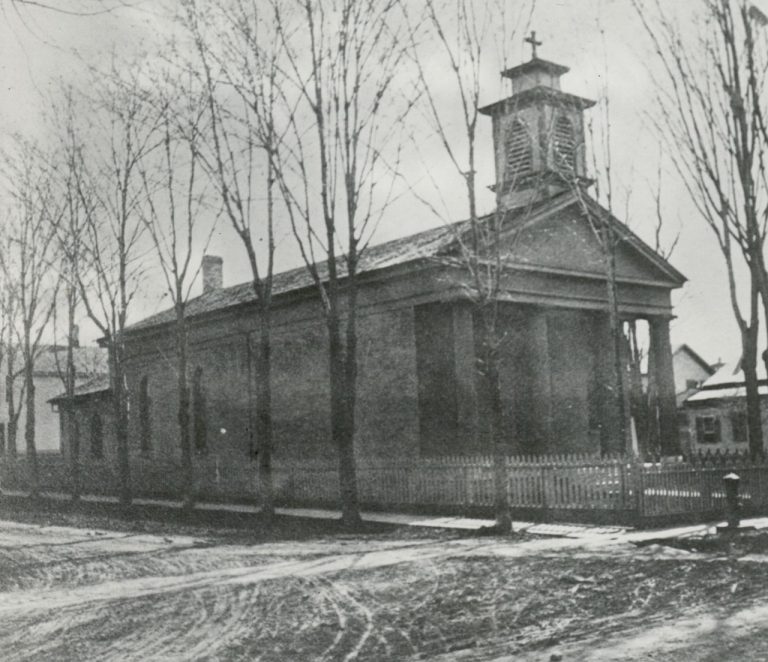

Today, the biggest hindrances to the Keep Mausoleum are Father Time, who catches up with us all, and Mother Nature, who relentlessly beats down with her elements. Although the tomb opened 152 years ago, it has stood the test of time. However, it faces an uncertain future and is one of the few remaining Otis Wheelock-designed buildings left in Watertown (the others being the Paddock Arcade, the last portion of the Iron Block and the First Presbyterian Church).

Like many older mausoleums, the care and upkeep sponsored by the original owners disappear further into the rearview mirror with each subsequent generation’s passing. It was only recently that descendants of the Hungerford family learned that Richard S. Hungerford, grandson of Orville, who passed in 1919, left behind a trust for which the interest was to be used for the upkeep of the family mausoleum, which, incidentally, also needs costly repairs. And like the Hungerford trust, the trust for the Keep Mausoleum’s status is unknown—though in the 1920s, it was reported to be earning $2,000/year in interest.

Recently, A. J. Hungerford, a descendant of the Hungerford family, had the opportunity to discuss the issues facing the Keep Mausoleum with local retired Architect, Edward G. Olley of GYMO, who wrote in an email—

Left unattended, cut limestone masonry, marble, terracotta, and brick building components survive poorly during the freeze-thaw cycles which occur during the inclement winter months; moisture wicks into the exterior mortar joints intended to seal and support the structural components, freezing and expanding, then breaking the mortar and often the stone or cast materials. This freezing and thawing takes place as often as daily throughout the winter season – often for many months.

A recent visit to the mausoleum in early January 2025 showed the moisture inside creating frost on the windows. This was as the temperatures were delving down into the single digits overnight, but after a recent warm period when climbing to 57º. This cycling, accompanied by unusual rainfall events, speeds up the rapid deterioration of the mausoleum, thus threatening its structural integrity, making even regular upkeep difficult to maintain.

Olley also offered the mausoleum a bleak assessment:

I predict then, based on my nearly 40 years of experience with these structures, that without major immediate restorative funding . . . for sustainable attention and future upkeep, the Mausoleum will become structurally unsound within 10 to 15 years—the fate of the building and deceased occupants left unknown.

The first step would be to have a qualified professional design team assess and determine what work is needed, calculate probable costs, and investigate possible funding sources—all factoring into a lead time that undoubtedly will grow longer as its days grow shorter.