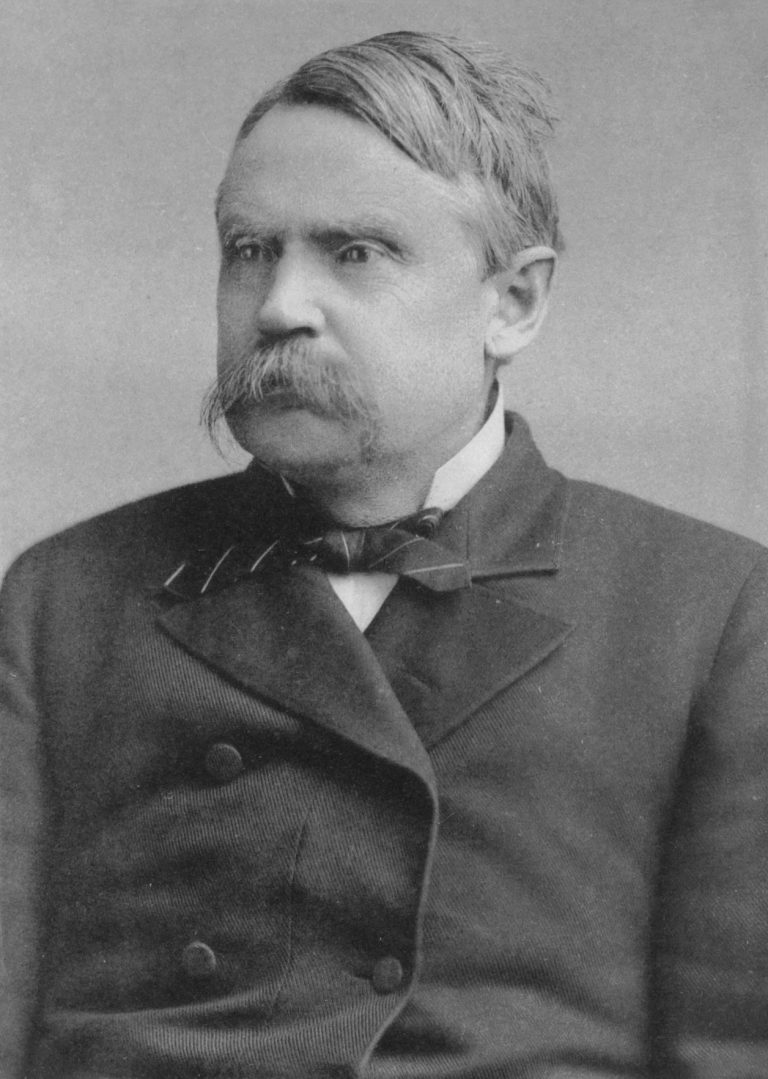

Attorney, Colonel, Brevet Brigadier Gen., Mayor, Senator Bradley Winslow’s Seven Isles Summer Home

Seven Isles was once the summer home of perhaps the most well-known veteran of the Civil War in Northern New York, Bradley Winslow, who purchased approximately five acres in 1879. The property stayed within the Winslow family until several years after Bradley’s second wife, Poppie H. Burdick Winslow, passed in 1928, leaving the estate intestate. A testament to Winslow’s popularity can readily be found in the number of mentions of his name in newspaper database queries during his life, well over 2,600, perhaps second to only Roswell P. Flower during the era.

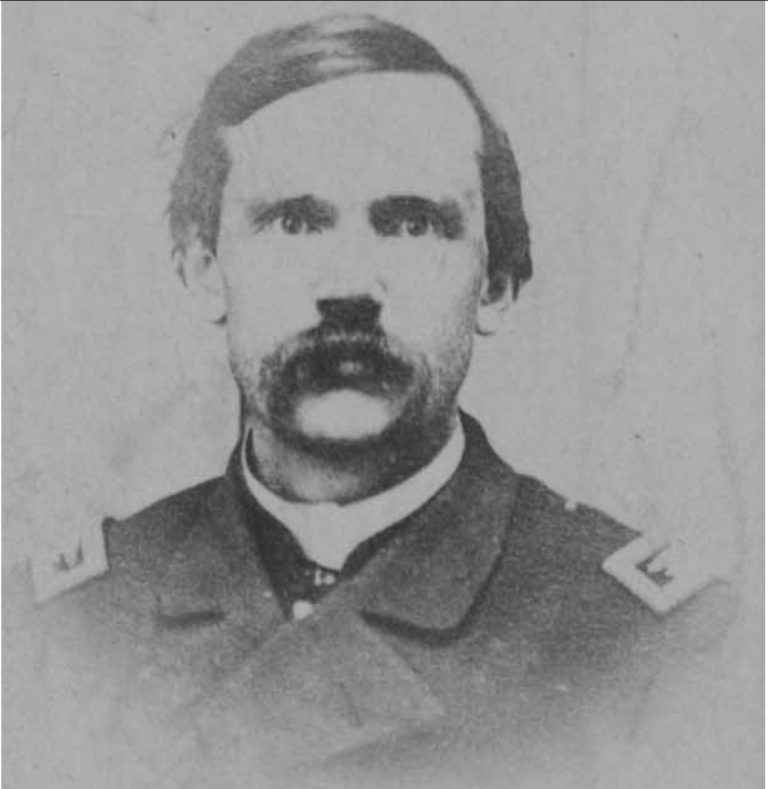

Born August 1, 1831, approximately two miles outside of Watertown, N.Y., Bradley Winslow was admitted to the Bar of New York State to practice law in the courtroom at the Woodruff House on July 1, 1855, after passing an exam given by James F. Starbuck and others, Starbuck a prominent attorney and later Senator from Watertown, whom Winslow went to work for.

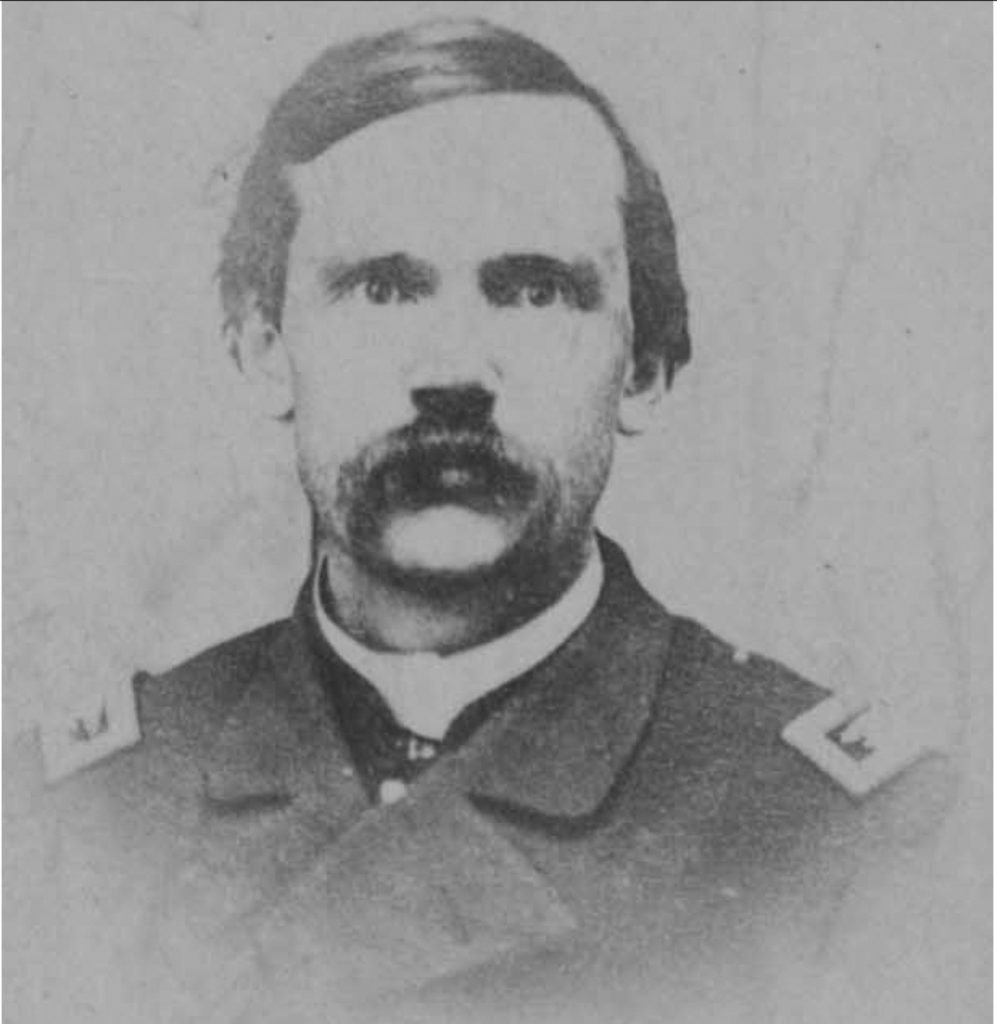

Within two years, Winslow opened his office and, by 1860, was District Attorney, a role he would walk away from just a year later, becoming one of the first to leave Watertown during a call for volunteers for the Civil War in 1861. Though he left civil life, Winslow’s education commissioned him the rank of Lieutenant in the 35th New York Volunteers. In the latter part of 1862, after participating in the second Battle of Bull Run, he resigned from his position as Lieutenant Colonel due to disability and returned to his law practice.

With the war continuing and Winslow recovering, he felt the call of duty again in 1864, organizing the 168th New York and assuming the rank of Colonel, and led his command into Fort Mahone, near Petersburg, Virginia, in what was described as one of the bloodiest charges of the Civil War. An article printed in the Watertown Daily Times in October of 1914, shortly after his death, detailed the battle–

At the head of the 186th regiment, New York Voluntary Infantry, (Winslow) was engaged in the movement on the South Side railroad in October of the same year. In February 1865, he took a prominent part in the storming of Petersburg. On April 2, Fort Mahone was the particular point assaulted by the regiment, which was the first to enter the enemy’s works, and it was highly complimented for its gallant charge, by its brigade and division commanders.

But the success was won at a fearful cost to the regiment, among the seriously wounded being Col. Winslow, who received a wound in the abdomen and narrowly escaped death. Big. Gen. Simon G. Griffin in his report especially mentioned Col. Winslow “for brave and gallant conduct” and recommended him for promotion.

It was written that Col. Winslow led the charge, beckoning his soldiers with a “Come on, boys!” On April 9, 1865, the day General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, President Abraham Lincoln, with the consent of the Senate of the United States, conferred upon Bradley Winslow the honor of Brevet Brigadier General for “Gallant and meritorious conduct in the assault before Petersburg, Va., April 2, 1865.” (Note: this was printed in the Oct. 13, 1914, Watertown Daily Times, the day before his death. Other sources state he received his Brevet the following year from President Andrew Johnson.)

The regiment was mustered out on June 2, 1865, with the discharges delivered two weeks later at Sackets Harbor, where Gen. Winslow was discharged. He was subsequently offered another rank but opted to return to civil life again as it was now a time of peace and was elected District Attorney the following fall. However, his ties to the military were short-lived, as Gov. Reuben E. Fenton appointed him as Brigadier General of the National Guard of New York in 1868. Winslow served as commander of the 16th Brigade for five to six more years.

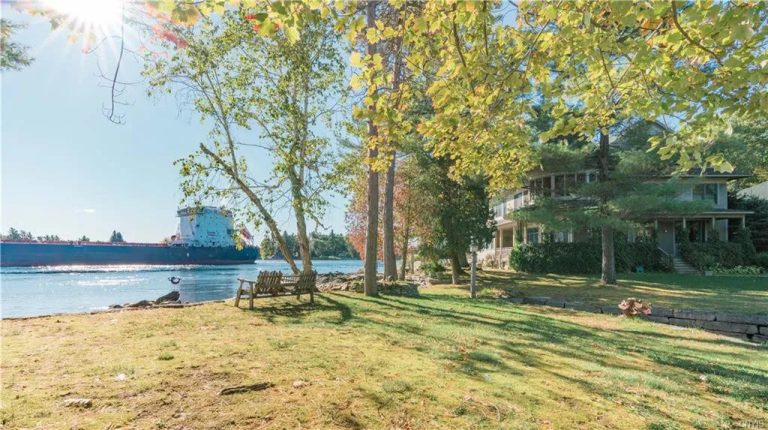

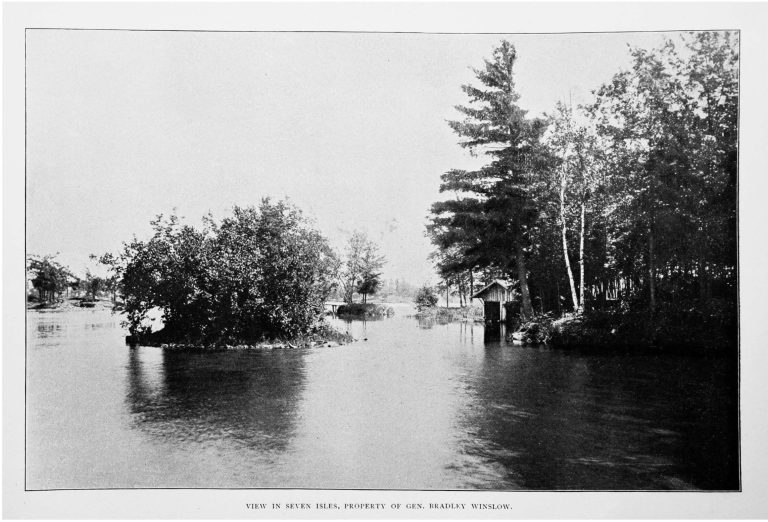

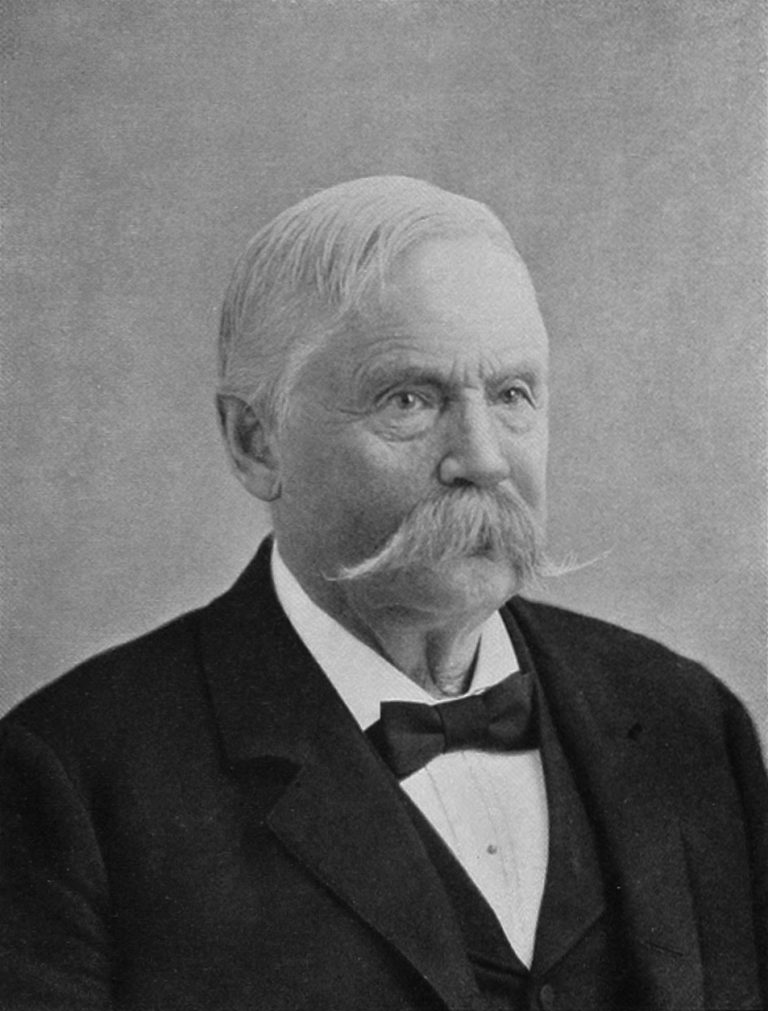

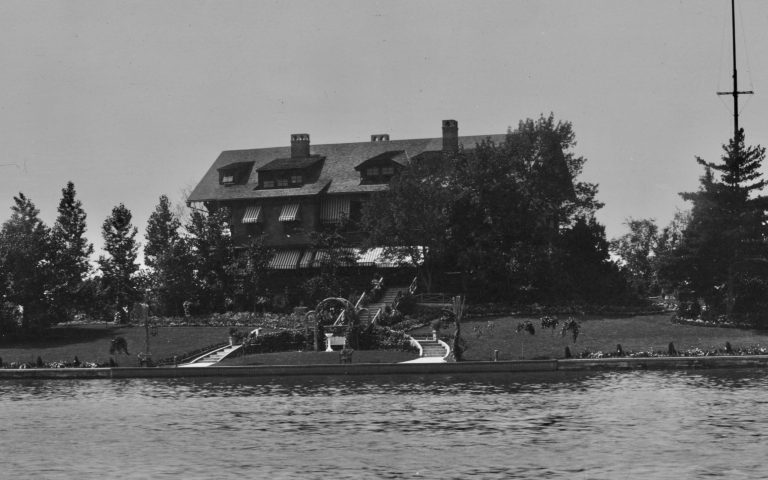

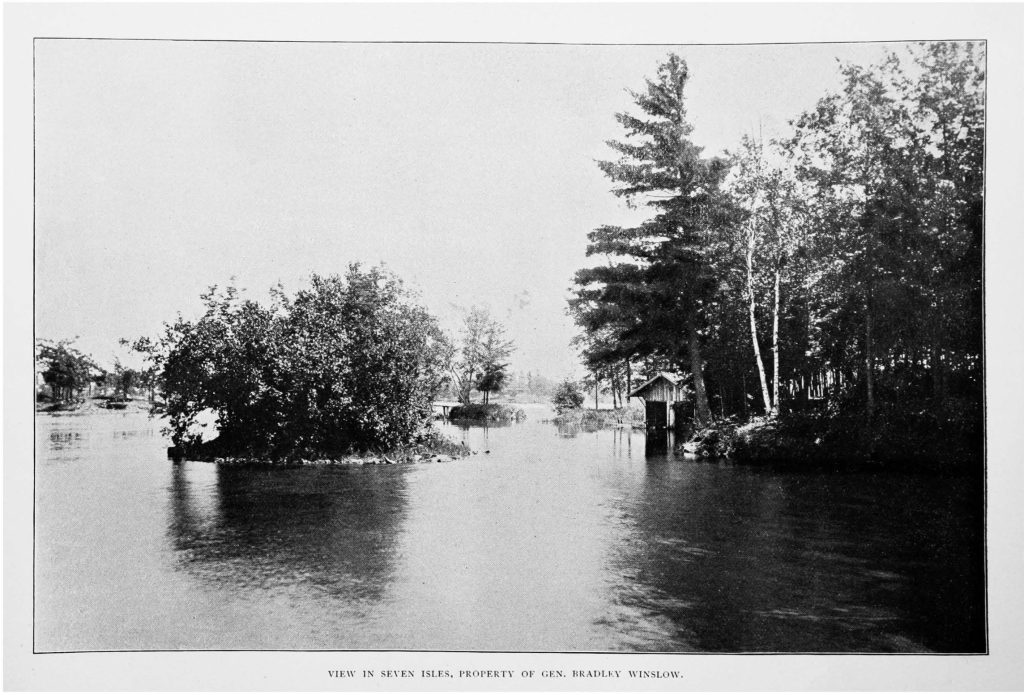

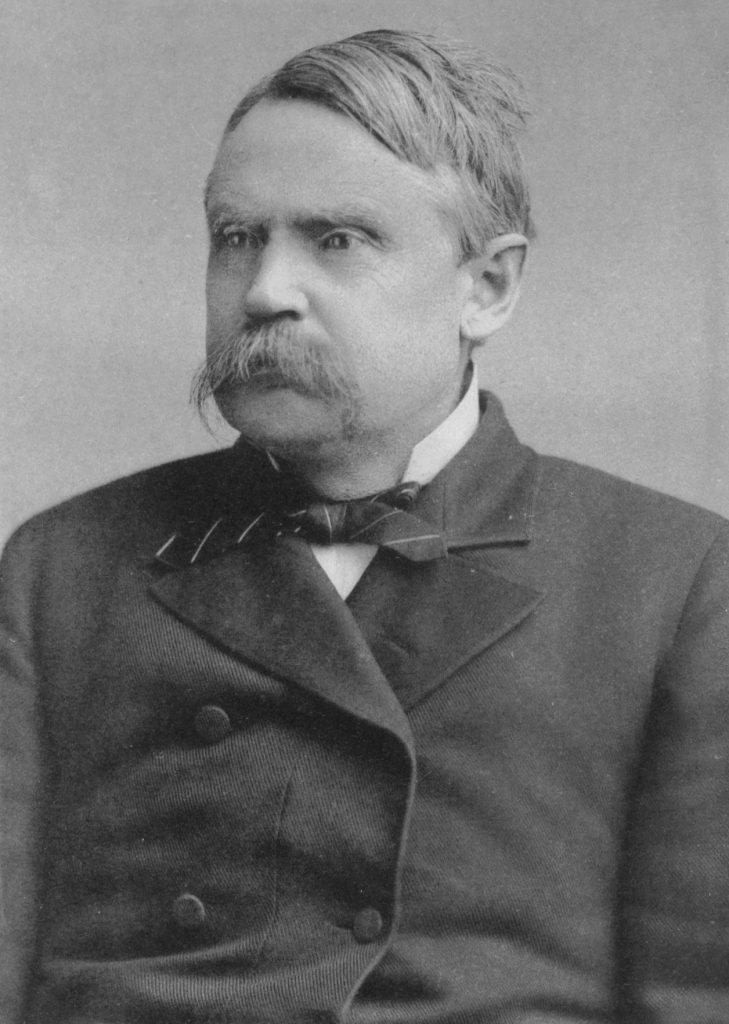

In 1874, Bradley Winslow served as the fourth mayor of Watertown, N.Y., declining an opportunity for re-election and later elected to the upper house of legislature of the State of New York in 1879, serving two terms. During this time, Winslow purchased several acres of land, formerly known as Knapp’s Island, on the St. Lawrence River, along with a portion of Bixby’s Point, the latter half (at least) from Charles and John F. Walton. The property, Seven Isles, consisted of a main house with several other cottages and, at one point, “The Bungalow Inn,” which was rented out (as were the cottages.)

For a number of years, Arthur Ebblie of Watertown managed the properties on Seven Isles, which drew people from all over the northeastern United States. Aside from numerous Civil War veterans, some of the notables who were guests included Rev. Dr. William Walter Smith and Mrs. W. Gordon Smith of New York. Rev. A. S. Durston and family of Syracuse. Prof. J. D. Paddock and family from East Orange, N.J.

During the last several years of Gen. Bradley Winslow’s life, he continued his law practice in the Flower Building. He dedicated much of his time and efforts to establishing a Memorial Hall for over 6,000 Veterans of Jefferson County, the effort consuming him and undoubtedly contributing to his failing health as he traveled far and wide for its support. He spent a good majority of the 1913-14 winter at Seven Isles with his second wife, Poppie, whom he married several years after the death of his first wife, Geraldine M. Cooper Winslow, in 1896, working on the Memorial Hall project.

His efforts were noted in the Watertown Daily Times on October 17, 1914, one week before his death–

Many of the details for the campaign for the erection of the Memorial Hall in Jefferson County were completed at a meeting Friday evening of the executive committee of the Memorial hall and Historical Association at the chamber of commerce rooms. A little pamphlet has been compiled by General Bradley Winslow, with the cover bearing a picture of a Lincoln and the contents explaining the reason for the erection of such a building and the direction as to how to vote in favor of it.

“The legislature of the state of New York, for the year 1914, by a passage of an act, which is chapter 864, of the laws of 1913, has opened the way for the people of the county to erect a Memorial Hall, and to expend $100,000 for that purpose, as a tribute to the memory of the soldiers and sailors who fought for the Union in the days of the Civil War to preserve its integrity. The act also provides for the preservation of the names of all who enlisted in the military service of the country since the passage of the Declaration of Independence.”

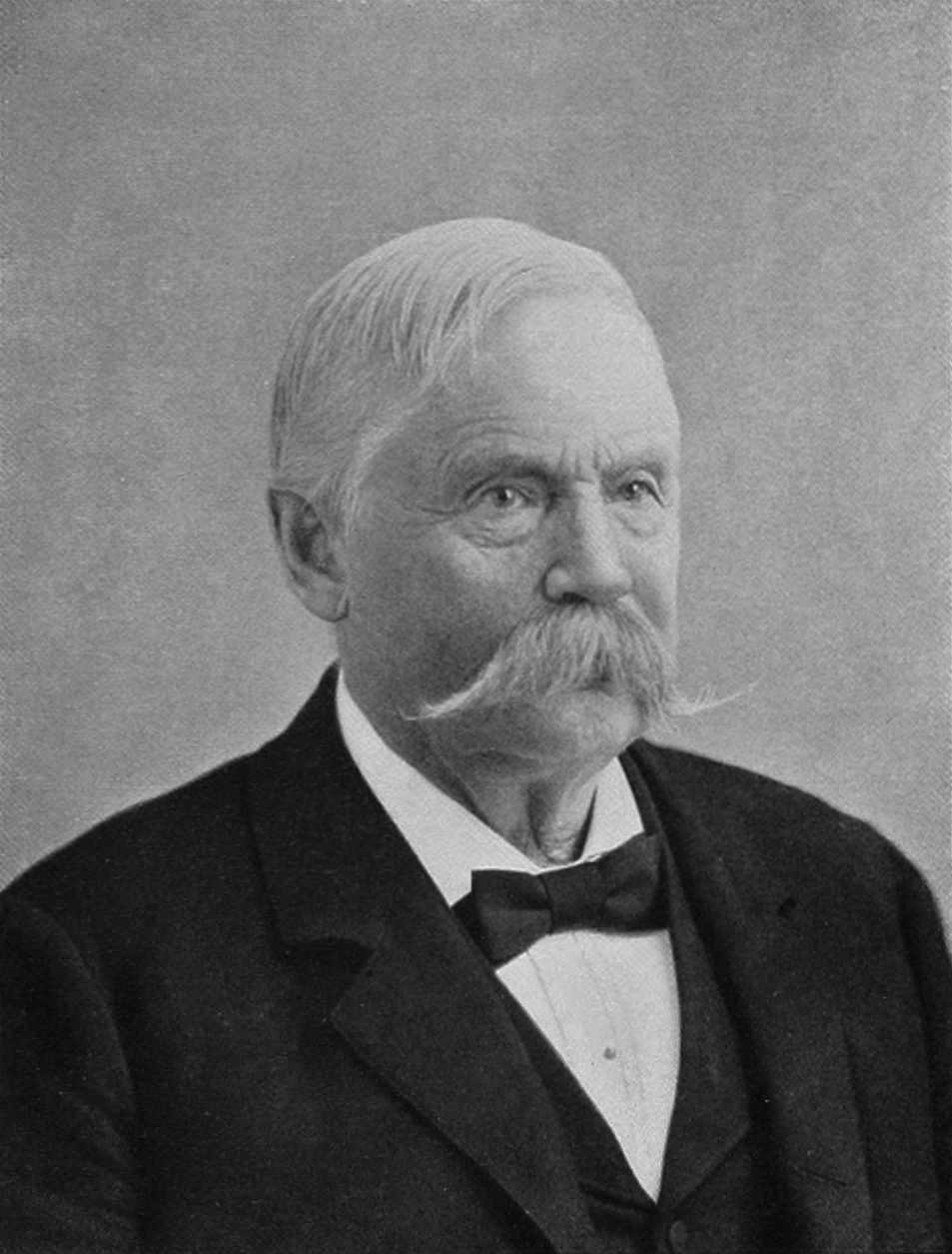

On October 23, Gen. Winslow was reported as being critically ill and taken to City Hospital, having suffered from a severe attack of pneumonia. At the age of 83, he continued to work both his law practice and the Memorial Hall project well into the twilight of his life, his patriotism bleeding over to many causes, including being a charter member of the Grand Army of the Republic (G. A. R.) in the State of New York, serving as first junior vice-commander and then as aide-de-camp on the staff of national commander, Albert D. Shaw, another North Country legend, Congressman, and brother-in-arms who fought at the Second Battle of Bull Run.

The next day, Gen. Bradley Winslow would pass. His efforts to secure votes for the Memorial Hall failed to garner enough votes, and less than two weeks later, the efforts quietly scuttled without its champion to shepherd them. The Times called it shameful, blaming area towns and villages of “jealousy,” with the prospective site for the hall to be built in Watertown, despite the city’s residents projected to bear 1/3 of its estimated $100,000 cost.

Three weeks after Winslow’s death, Captain Kendrick W. Brown penned a tribute to the General he served under in the Watertown Daily Times. It’s a poignant tribute to their friendship, much of it recounting times at Seven Isles, printed in its entirety below–

The general is dead. He was 83 years of age. His name has been a household word in my family for more than 50 years. General Bradley Winslow, second brigade, second division, Ninth corps, Army of the Potomac.

He was one of my ideals of a fine looking officer. A vision of my military life in the sixties, which will linger with me till the great Divide is passed—shows the general—sword in hand—arm outstretched high above his head, leading the brigade in a terrific charge, up an incline—he a hundred feet or more ahead of the line, leaning forward as if to stem the storm of bullets which filled the air and calling “Come on boys” and then there came the fateful ball that pierced his side and down he went. A wound which he never fully recovered.

“The colonel is dead”—our old commander of the 186th New York volunteers infantry—what a fine record he leaves today, October 28th, 1914—they lay a warrior to rest in Watertown, New York, the home of his youth, manhood and declining years. In how many places I can see his stalwart form, six feet, and more than four inches tall, riding a fine horse at the head of his command, marching, drilling or on review.

In 1898 after a separation of 32 years he went with me and my wife, Lydia and Faith to Sackets Harbor to visit Captain McWayne and family for a few days. Learning that we were going, he said to use, “Can I go with you?” and no one but a comrade can know the joy it gave us to welcome him and he invited us to the captain’s wife and daughter to spend a week with him in his beautiful summer home on his island “Seven Isles.”

Oh what a visit we had living over the days of our four years together in the sixties. He went out as captain of Company A, 35th New York. He was an attorney by profession, a very just and upright man—but not a member of any church. One day, sitting on the rocks of his island home, he and I alone, watching the blue waters of the river rolling by, we were having a heart to heart talk, of higher and holier things than common, when he says to me:

“Captain, are you a Christian?”

“I hope so—I profess to be.”

“Do you say grace at your table when you are at home?”

“I always do unless my wife or one of my children do when asked to do so.”

“Would you mind if I asked you to say grace at my table?”

“I thank you, general, for asking the question. Nothing would give me more pleasure.”

“Well, I wanted to ask you all the time, but you know how it is—so many people who are church people, but do not do such things.”

“My father was an old Methodist class leader, and he always had grace at table and family prayers.”

When we finally parted we were rowed two miles down the river to Alexandria Bay, where we caught the steamer, which did not stop at “Seven Isles,” and came right back, passing the general’s cluster of islands—and there on his dock extending out into the shallow water 50 or 75 feet stood the old general—his form erect—his hat removed and held aloft to give us a silent salute and goodbye as we steamed past him.

We all gathered on the side of the upper deck nearest him and no one spoke—as there was no more to be said. He had spoken our last words and probably both felt it was our last view of each other in this life, but two years ago I did grasp his hand and look into his eyes again for five minutes, and was very grateful for the tender greeting.

For 55 years he was my unshaken friend and nothing ever came between us. I was always proud of his friendship and I did not wait till he was gone to put flowers on his grave to show my appreciation of his kindly offices towards me, but have been able to express by word of mouth and pen my high regard of him as a man, my respect for him as a citizen and an officer, and my tender affection for him as a comrade and friend in many ways before penning this little tribute to his memory.

Sincerely and with bowed and uncovered head.

Kendrick W. Brown