The Experimental Balloon Flights of the Mid 19th Century In Watertown, N.Y.

Balloon flights in the modern era of billionaires touring the lower reaches of outer space in their personal rockets don’t elicit much of a response. Balloon flights in the early to mid-1800s, however, were very much the equivalent of Major Tom to Ground Control.

The event, trending upward in Europe for some time (pun intended), took a while to catch on in the United States, and the first actual successful flight didn’t occur until 1793 by the Frenchman François Blanchard. It wouldn’t be until Charles Ferson Durant’s successful flight in 1830 that an American could lay claim to doing the same.

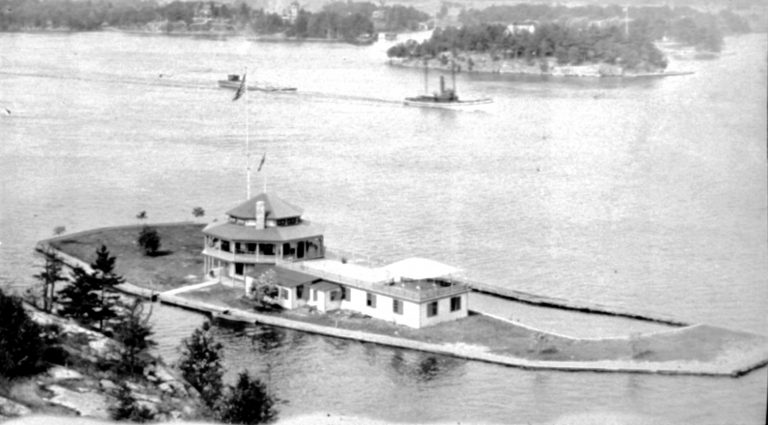

After some time, Ballooning finally caught on and became a popular entertainment venue at our fairs and carnivals, where they drew thousands of curious onlookers. One of the eager aeronauts at the time was John Wise. After finding a financier in O. A. Gager, the Atlantic was built: a 50,000 cubic foot balloon with a lifeboat attached beneath it with the purpose of crossing the Atlantic to Europe.

According to one source

On July 2, 1859, Wise, LaMountain, Gager, and a reporter left St. Louis and flew 809 miles (1,302 kilometers) in this balloon to Henderson in Jefferson County, New York. The flight, which lasted 19 hours 50 minutes, was threatened by a violent storm that almost drove them into Lake Ontario. Wisely, the aeronauts, instead of relying on their lifeboat, cut it adrift and gained the additional lift they needed.

Wise also jettisoned a bag of mail consigned to the group by the United States Express Company. This was the earliest airmail delivery in the United States. The flight established an official world distance record for non-stop air flight that would stand until 1910.

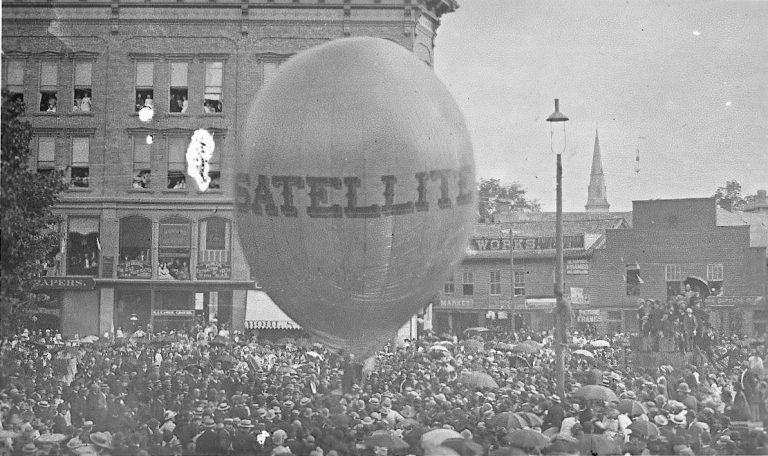

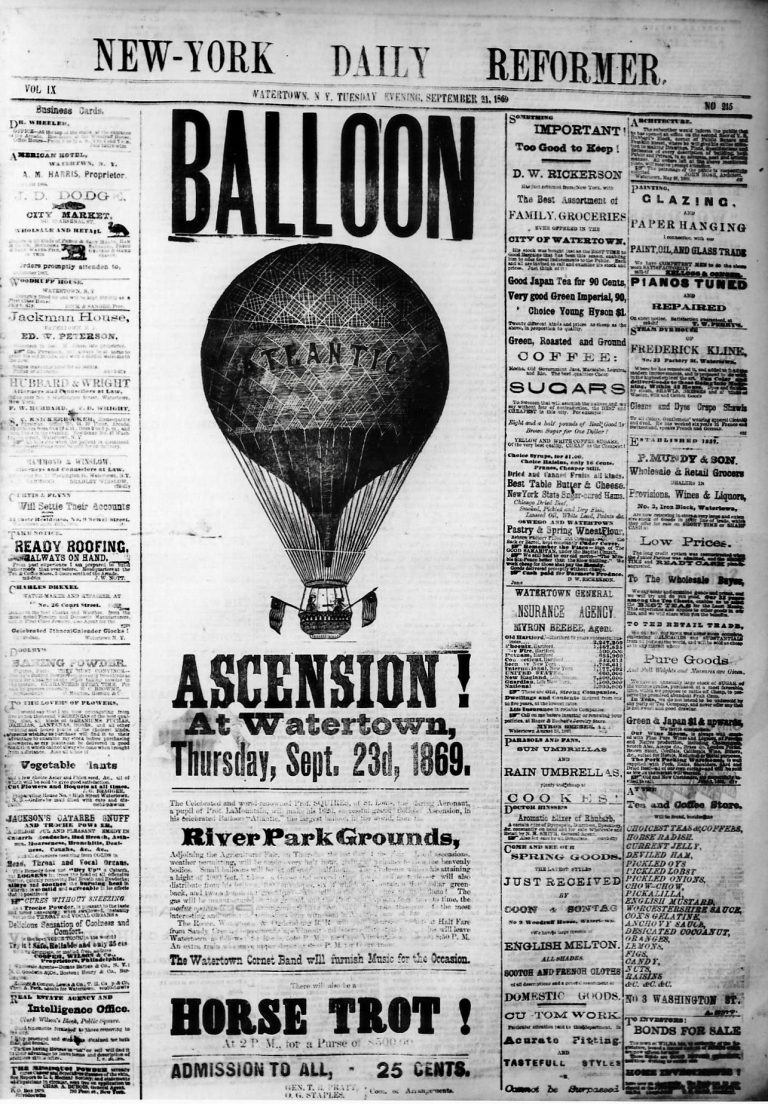

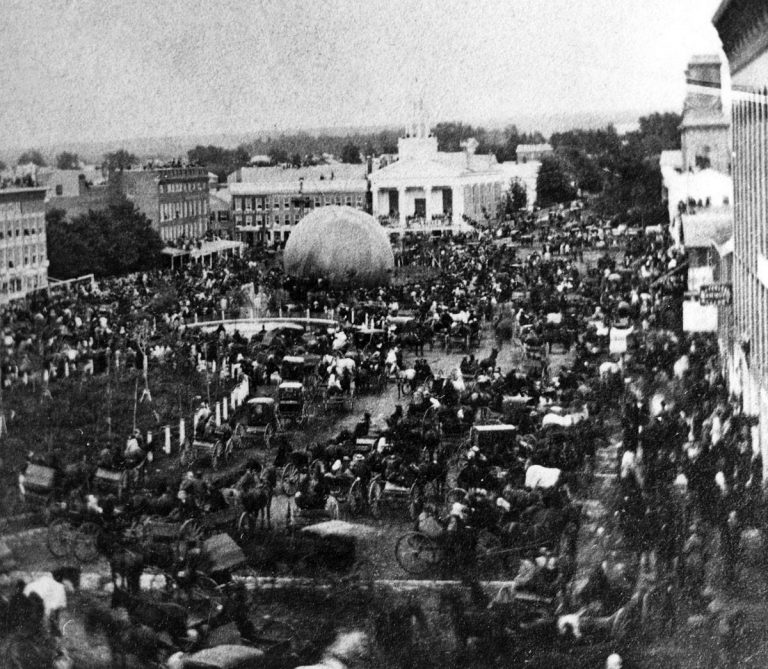

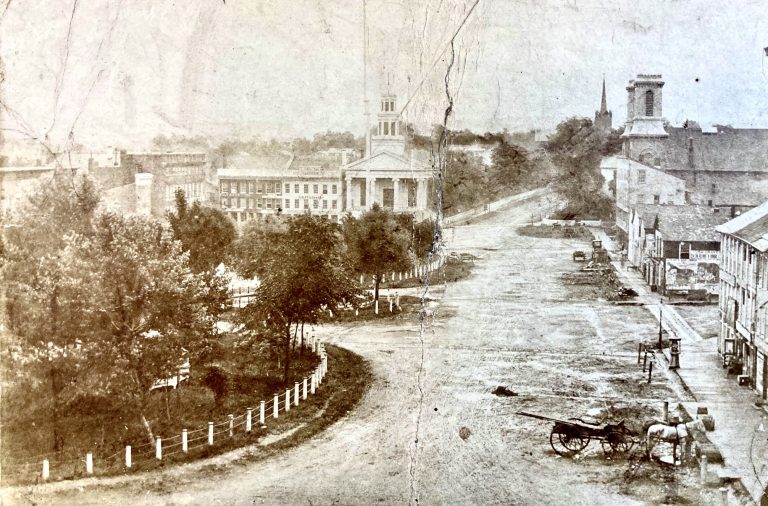

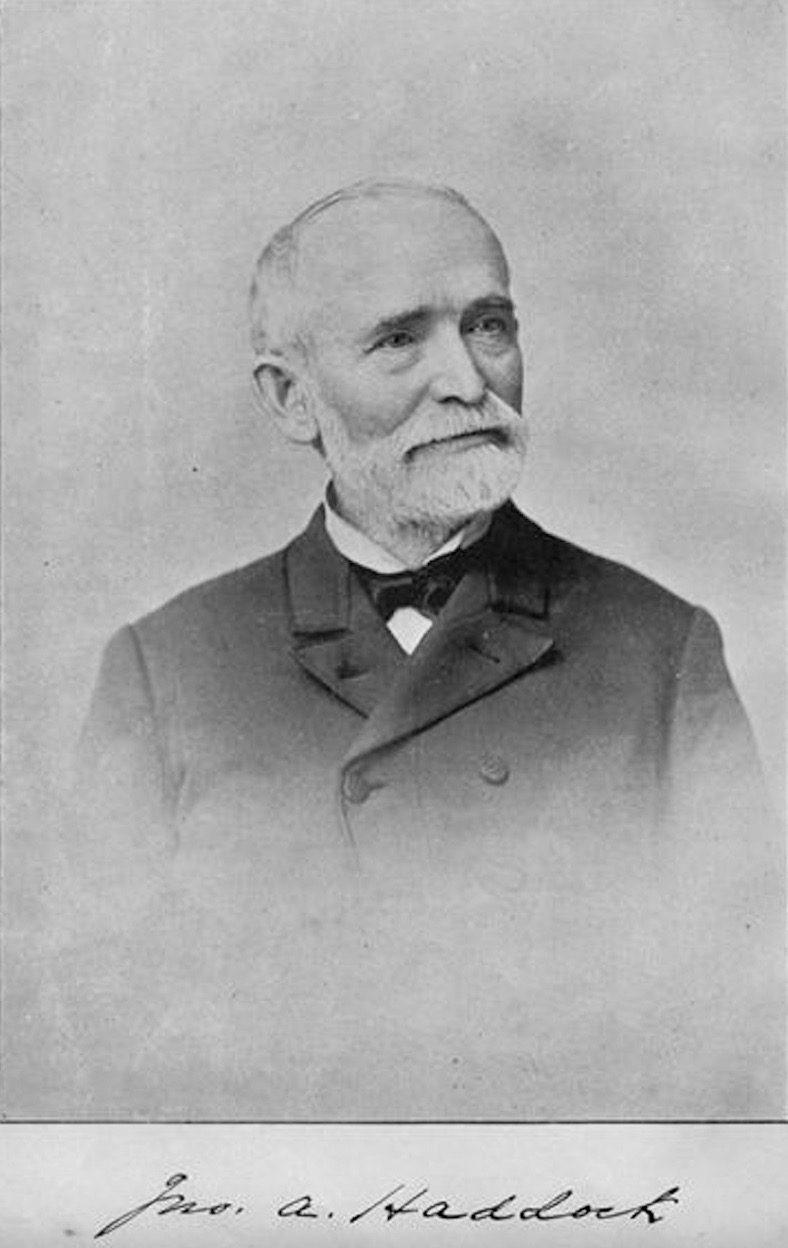

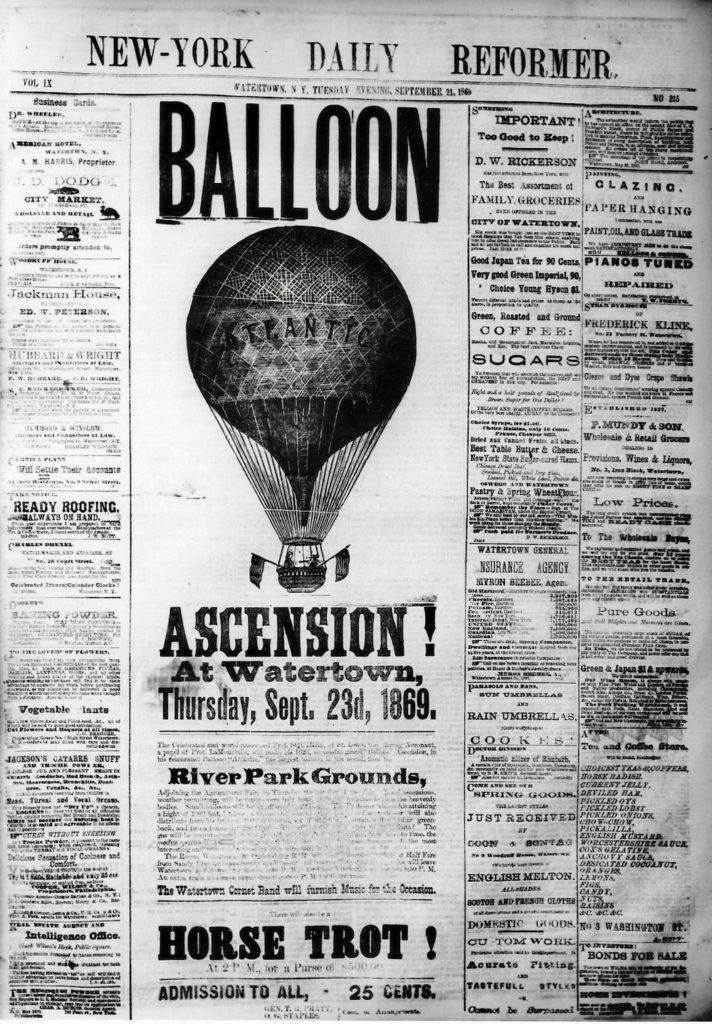

John LaMountain, another aeronaut who accompanied that balloon flight, would take possession of the damaged Atlantic and make repairs with plans for another flight. In September, he would be accompanied by John Haddock, then editor of the Watertown Reformer, to make a short ascension from Public Square.

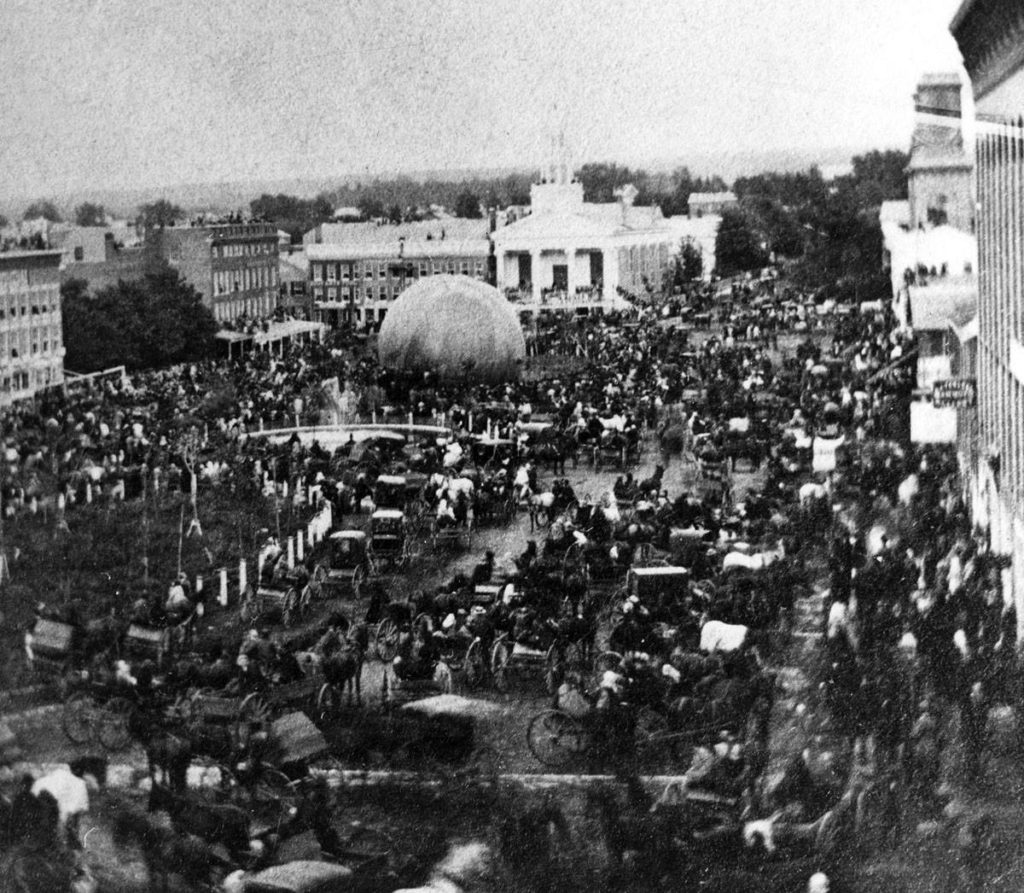

The Central City Courier would report LaMountain and Haddock would make their ascension in the celebrated balloon “amidst the shouts of 20,000 people.” What follows is Haddock’s amazing account of that short ascension that became a struggle for survival in a wilderness far from home with no food, proper clothing, or shelter. The account has been edited but can be read in its entirety in John Haddock’s historical book, Growth of a Century, published in 1894.

Major John A. Haddock’s Great Balloon Voyage With Professor LaMountain

According to Mr. Haddock, the voyage was intended to be “short and pleasant” but became a harrowing journey of survival in one of the longest balloon rides in history at that point. The Atlantic, which had flown from St. Louis to Watertown and crashed, was ready to go again but would have to wait two days on account of a storm.

As John Haddock tells the story in Growth of a Century, the balloon was ready to go on September 22, 1859—

Every arrangement had been made for a successful inflation, and at 27 minutes before 6 p.m., the glad words, “all aboard,” were heard from LaMountain and that distinguished aeronaut and myself stepped into the car. Many were the friendly hands we shook—many a fervent “God Bless you,” and “happy voyage,” were uttered—and many handkerchiefs waved their mute adieus.

“Let go all,” and away we soared; in an instant all minor sounds of earth had ceased, and we were lifted into a silent sphere, whose shores were without an echo, their silence equaled only by that of the grave. No feeling of trepidation was experienced; an extraordinary elation took possession of us, and fear was as far removed as though we had been sitting in our own rooms at home.

In eight minutes after leaving the earth, the thermometer showed a fall of 24 degrees. It stood at 84 when we left. The balloon rotated a good deal, proving that the ascending with great rapidity.

At 5:48 thermometer stood at 42, and falling very fast.

At 5:50 we were at least two miles high—thermometer 34. An unpleasant ringing sensation had now become painful, and I filled both ears with cotton.

At 5:52 we put on our gloves and shawls—thermometer 32. The wet sandbags now became stiff with cold—they were frozen.Ascending very rapidly.

At 5:54 thermometer 28, and falling. Here we caught our last sight of the earth by daylight. I recognized the St. Lawrence to the southwest of us, which showed we were drifting nearly north.

At 6 o’clock we thought we were descending a little, and LaMountain directed me to throw out about 20 bounds of ballast. This shot us up again—thermometer 26, and falling very slowly.

At 6:05 thermometer 22—my feet were very cold. The Atlantic was now full, and presented a most splendid sight. The gas began to discharge itself at the mouth, and its abominable smell, as it came down upon us, made me sick. A moment’s vomiting helped my case materially. LaMountain was suffering a good deal with cold. I passed my thick shawl around his shoulders, and put the blanket over our knees and feet.

At 6:30 thermometer 18.

We drifted along until the sun left us, and in a short time thereafter the balloon began to descend.We must have been, before we began to descend from this height, 3.5 miles high.

At 6:32 thermometer 23; rising.We were now about stationary, and thought we could were sailing north of east. We could, we thought, distinguish water below us, but were unable to recognize it.

At 6:38 we threw over a bag of sand, making 80 pounds of ballast discharged, and leaving about 120 pounds in one hand. We distinctly heard a dog bark.Temperature 28—and rising rapidly.

At 6:45 the thermometer stood at 33.

At 6:50 it was dark, and I could make no more memoranda. I put up my note boo, pencil and watch, and settled down in the basket, feeling quite contented. From this point until next morning I give my experiences from memory only. The figures given were made at the time indicated, and the thermometric variations can be depended on as quite accurate.

As Haddock and LaMountain floated in the dark, they would hear various sounds, letting them know they were close to civilization. A locomotive whistle. Wagons occasionally rumble over the ground or a bridge. Farmers’ dogs barking “as if conscious there was something unusual in the sky.” At about 8:30, lights were visible below them, along with the sound of a roaring waterfall. They began to descend into a valley near a very high mountain but decided to go up again.

20 minutes later, they began to descend again – this time in darkness with no sign of civilization. Rather, they were over a great wilderness and figured the sooner they descended, the better at this point, and they did so by latching onto a tree.

As Haddock continues his recollection of events–

We rolled ourselves up in our blankets, patiently waiting for the morning. The cold rain spouted down upon us in rivulets from the great balloon that lazily rolled from side to side over our heads, and we were soon drenched and uncomfortable as men could be.

After a night passed in great apprehension and unrest, we were right glad to see the first rays of coming light. Cold and rainy the morning at last broke, the typical precursor of other dismal mornings to be spent in that uninhabited wilderness.

We waited until 6 o’clock in hopes the rain would cease, and that the rays of sun, by warming and thereby expanding the gas in the balloon, would give us ascending power sufficient to get up again, for the purpose of obtaining a view of the country into which we had descended.

Taking a good portion of equipment out of the Atlantic, the two were able to rise up in the balloon and see they were surrounded by unbroken wilderness of lakes and spruce. They began to recognize they had gone too far through a miscalculation of the velocity of the balloon.

They descended once again. Hungry, with no protection at night, not knowing how far away from habitation, and not having the means to make a fire, they were “about as well equipped for forest life as were the babes in the woods.”

Guessing at their whereabouts led them to believe they were either in John Brown’s tract or in the wilderness lying between Ottawa City and Prescott, Canada. Tramping through the forest, they came across the head of a half-barrel with pork. The stamp on it read “Mess Pork. P.M. Montreal.”

The two would find a creek and travel alongside it, going westwardly, crossing it on a log about noon on Friday. There, on its southern shore, they found a path that led to a deserted lumber road and a log shanty on the opposite bank. Deciding to cross it, they grabbed some small timbers and, with a makeshift raft, LaMountain crossed first and shoved the raft back over. Haddock’s weight was heavier, and the raft sank under. He would make it short with all his strength to do so, “scarcely able to stand” as cold as he was.

Inside the abandoned hut, they spent the night, Haddock telling thoughts as they lay there; “home, children, wife, friends, with their sad and anxious faces, rose up reproachfully before us as we tried to sleep.”

The next morning, they decided to build a stronger raft and take it down the river in hopes of coming to civilization. As they pushed off, Haddock noted, “a miserable crow set up a dismal cawing—an inauspicious sign.” With nothing else to eat, they both made quick of the only thing they could find: one raw frog apiece.

As night came, they decided not to stop and just keep heading downriver “through shades of awful forests, whose solemn stillness seemed to hide from us the unrevealed mystery of our darkening future.” By 10 o’clock at night, the rain started again. At 3 a.m., they would stop again, but only for a few hours, as by 8 a.m., they were back on their raft with hope fading as the stream narrowed, rushing over large boulders and between rocky shores.

After dismantling their raft, they lugged it past the rapids that lay ahead. “This was the most trying and laborious work of a whole life of labor,” Haddock would write. After reassembling their timber, they made their way down the river. About an hour later, they came to a large lake, “about 10 miles long by six broad.” Haddock found but one clam to eat and gave it to LaMountain, who was much weaker at this point.

Haddock would continue—

A few tears could not be restrained and my prayer was for a speedy deliverance or speedy death. While my companion was asleep, and I busily poling the raft along, I was forced to the conclusion, after deliberately canvassing all the chances, that we were pretty sure to perish there miserably at last. But I could not cease my efforts while I had strength, and so around the lake we went, into all the indentations of the shore, keeping always in shallow water.

The day at last wore away, and we stopped at night at a place we thought least exposed to the wind. We were cold when we laid down, and both of us trembled by the hour, like men suffering from a severe attack of the ague. The wind had risen just at night, and the dismal surging of the waves upon the shore, formed, I thought, a fitting lullaby to our disturbed and dismal slumbers.

By this time our clothes were nearly torn off. My pantaloons were split up both legs, and the waistbands nearly gone. My boots were mere wrecks, and our mighty wrestlings in the rapids had torn the skin from ankles and hands. LaMountain’s hat had disappeared; the first day out he had thrown away his woolen drawers and stockings, as they dragged him down by the weight of the water they absorbed.

The following morning, they came to a broad northern stream that they thought might be the outlet they were seeking to take them to Ottawa. It had now been four full days since they had had a meal: a frog apiece, four clams, and a few wild berries “whose acid properties and bitter taste had probably done us more harm than good.”

With strength fading fast, they traveled about a mile when they heard the sound of a gun. Then another shot. “No sound was ever so sweet to us.” Re-energized, they continued about a half mile when Haddock called LaMountain’s attention to what he thought was smoke curling up among the trees by the side of a hill.

“My own eyesight had begun to fail very much, and I felt afraid to trust my dulled senses in a matter so vitally important,” Haddock would write. LaMountain thought he saw a birch canoe on the shore below. It was only a few moments later that the two saw blue smoke rolling above the treetops.

Haddock would write further—

Leaving LaMountain to guard and retain the canoe, in case the Indian proved timid and desired to escape from us, I pressed hurriedly up the bank, following the footprints I saw in the damp soil, and soon came upon the temporary shanty of a lumbering wood, from the rude chimney of which a broad volume of smoke was rising.

I halloed—a noise was heard inside, and a noble-looking Indian came to the door. I eagerly asked him if he could speak French, as I grasped his outstretched hand. “Yes,” he replied, “and English, too!”

He drew me into the cabin where I saw the leader of the party, a noble-hearted Scotchman named Angus Cameron. I immediately told him my story; that we had come in there with a balloon, were lost, and had been over four days without food—eagerly demanding to know where we were.

Imagine my surprise when he said we were ONE HUNDRED AND EIGHTY MILES DUE NORTH OF OTTAWA, near 300 miles from Watertown, to reach which would require more than 500 miles of travel, following the streams and roads.We were in a wilderness as large as three States like New York, extending from Lake Superior on the west, to the St. Lawrence on the east, and from Ottawa, on the south, to the Arctic circle.

Cameron’s party consisted of four people who had just prepared their dinner. As Haddock wrote, “All that the cabin contained was freely offered to us, and we BEGAN TO EAT. Language is inadequate to express our feelings. Within one hour, the clouds had lifted from our somber future, and we felt ourselves to be men once more.”

After Cameron had finished some business in the area, Haddock and LaMountain, on their ninth day since leaving Watertown, headed back to the balloon, where they decided to abandon it. They would have difficulty finding Indians to help them on their way back.

As Haddock told it—

LaMab McDougal had told his wife about the balloon, and she, being superstitious and ignorant, had gossiped with the other squaws, and told them the balloon was a “flying devil.” As we had travelled in this flying devil, it did not require much of a stretch of Indian credulity to believe that if we were not the Devil’s children, we must at least be closely related.

With some help, Haddock and LaMont would soon find themselves entering Ottawa, where Haddock wrote—

I do not know how the people of Ottawa so soon found out who we were—but suppose the telegraph operator perhaps told some one; and that “some one” must have told the whole town for in less than half an hour there was a tearing, excited, happy, inquisitive mass of people in front of the grand hotel there.

The clerk of which, when he looked at our ragged clothes and bearded faces, at first through he “hadn’t a single room left,” but who, when he found out that we were the lost balloon men, wanted us to have the whole hotel, free and above board; and had tea and supper and lunch, and “just a little private supper, you know!” following each other in rapid, yet most acceptable succession.

The next morning, Haddock and LaMountain would leave Ottawa via a special engine, taking them quickly to Prescott, across the St. Lawrence, and to Ogdensburg, where they had a similar reception with only 75 miles to go.

At Watertown, which had been Haddock’s home since boyhood, “the enthusiasm had reached fever heat, and the whole town was out to greet the returning aeronauts.” As he told it—

They had out the old cannon on Public Square, and it belched forth the loudest kind of a welcome. My family, of course, suffered deeply in my absence.Everybody had given us up for dead, except my wife. I felt very cheap about the whole thing, and quite certain I had done a very foolish act.

Not so the people—they thought it a big thing to have gone through with so much, and yet come out alive.