Taggart Paper Mill Had Served Many Purposes Over The Years, Destroyed By Fire In 1972

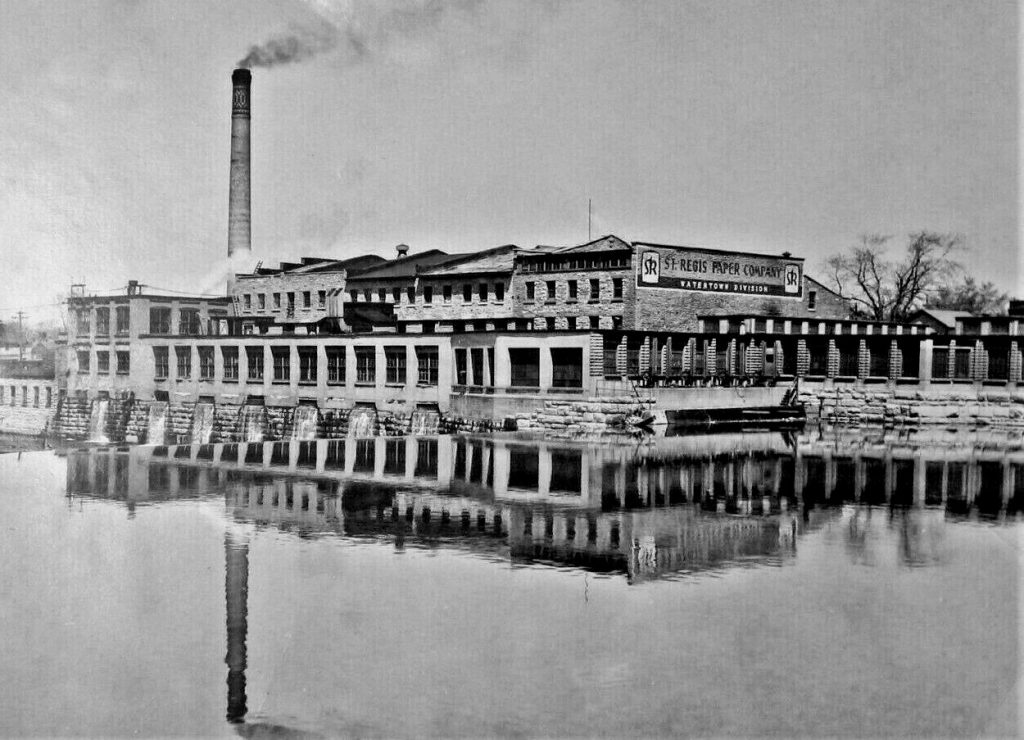

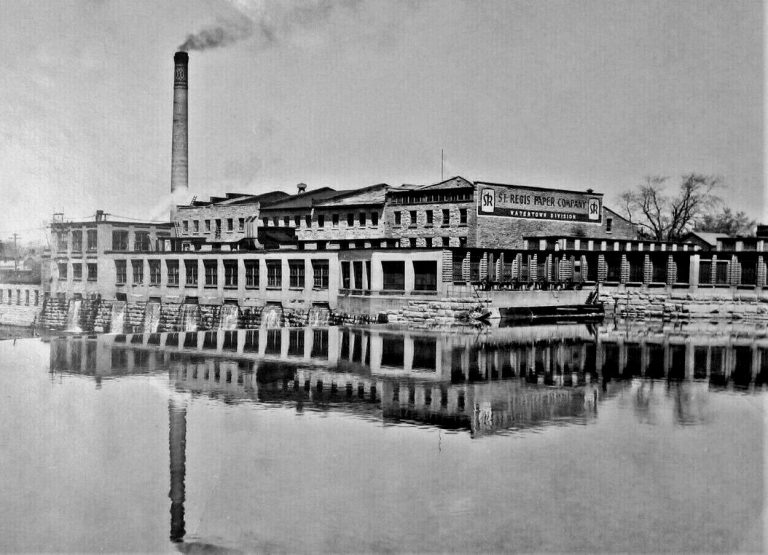

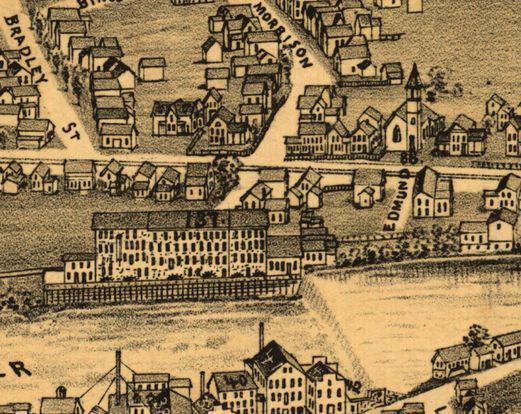

Constructed of limestone in 1843-45 by General William H. Angell, the former Taggart Paper Mill on West Main Street was originally used as a distillery and grist mill. It wouldn’t be until 1866, when the West, Palmer & Taggarts Co. purchased it, that it would be used for manufacturing paper-related products, namely, paper bags.

As written in Through Eleven Decades of History, by Joel H. Monroe—

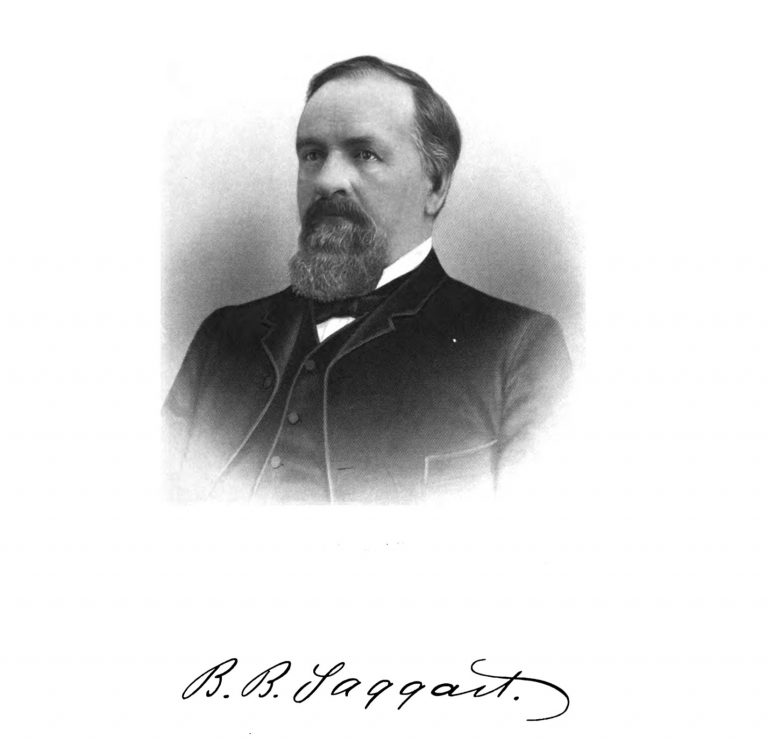

The old distillery and flouring mill built in 1843-45 by William H. Angell at the lower dam was converted into a paper mill in 1864, by B. B. Taggart and A. H Hall. This, a little later, became West, Palmer & Taggart, makers of manilla paper. In 1887, B. B. and William Taggart became owners of the property, at which time they organized a stock company, known as the Taggart Bros. Company.

Although the Taggarts didn’t invent the paper bag, Byron Taggart did aid in the invention of the “Stillwell” machine, which was limited to very few mills at the time. According to The Growth of a Century, by John Haddock and Eli Thayer–

One machine that makes a bag with satchel-bottom, direct from the roll, at the rate of 3,600 finished bags per hour, completing with ease 25,000 fifty-pound flour sacks in 10 hours. The use of this, the “Stillwell” machine, is limited to very few mills. Mr. B. B. Taggart was one of the first to aid in developing the original device, and when he sold his interest in the machine at a round of profit, he reserved the right to manufacture at his own mills. This very ingenious and complicated machine takes in paper at one end and turns out bags at the other with a rapidity that is astonishing.

In 1958, the Taggart Paper Mill, then owned by Abe Cooper, who purchased it four years prior, would stop production for a seven-month period, re-opening in January of the following year when it recalled 45 employees for work. At the time, the mill produced mill wrappers, folder stock, tube stock, and better grades of Kraft paper. The re-start would be short-lived as the mill would soon sit idle for a number of years.

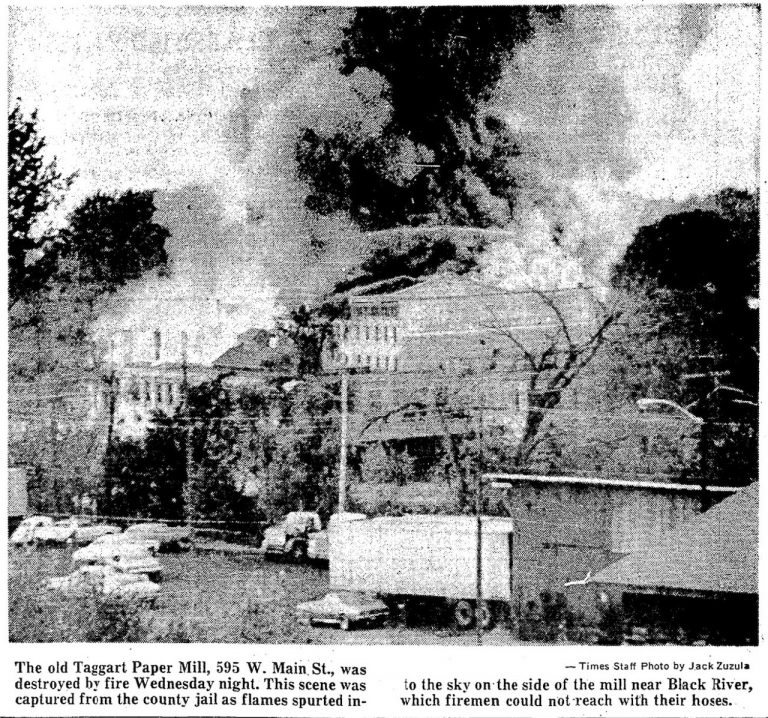

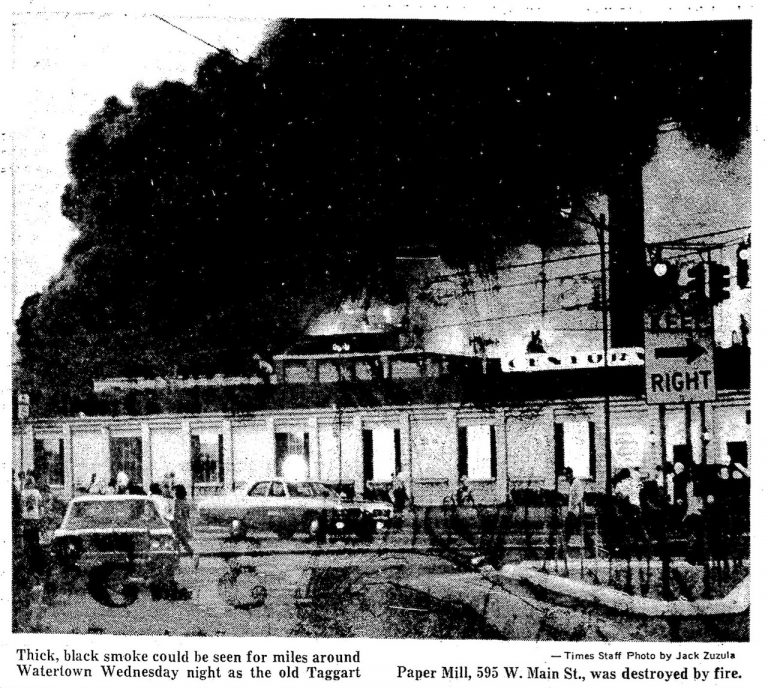

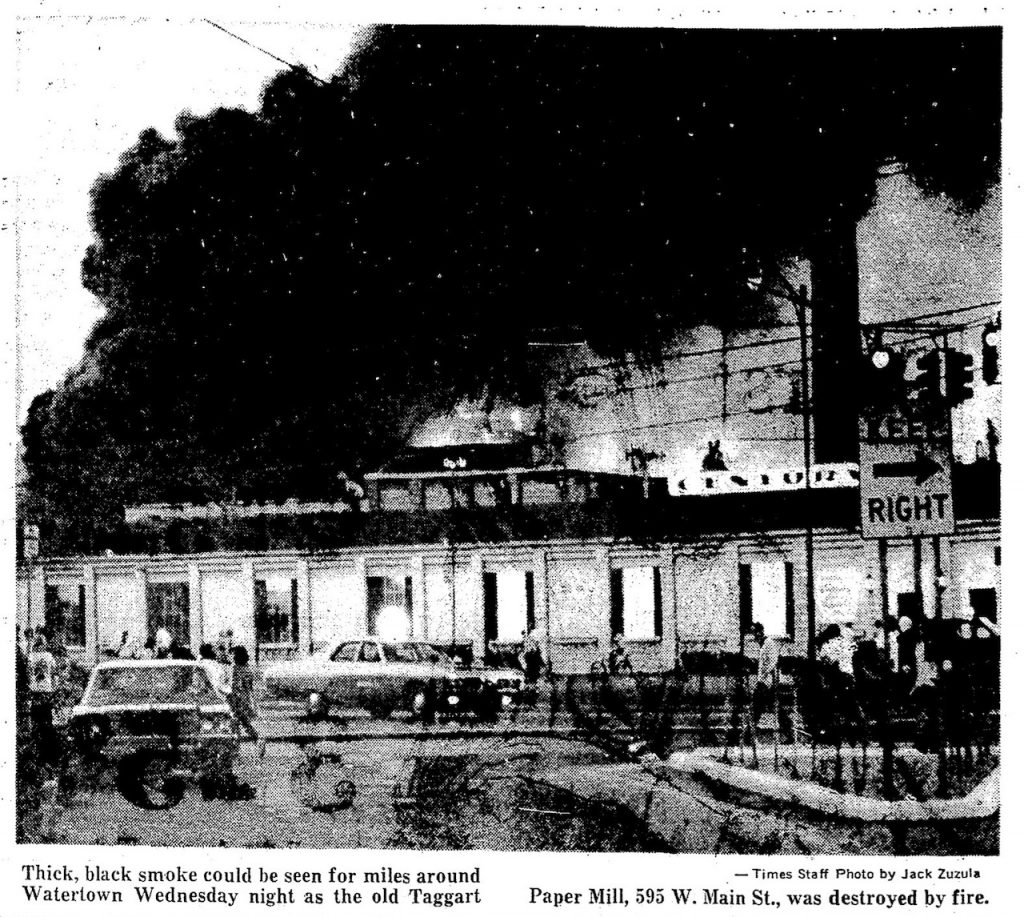

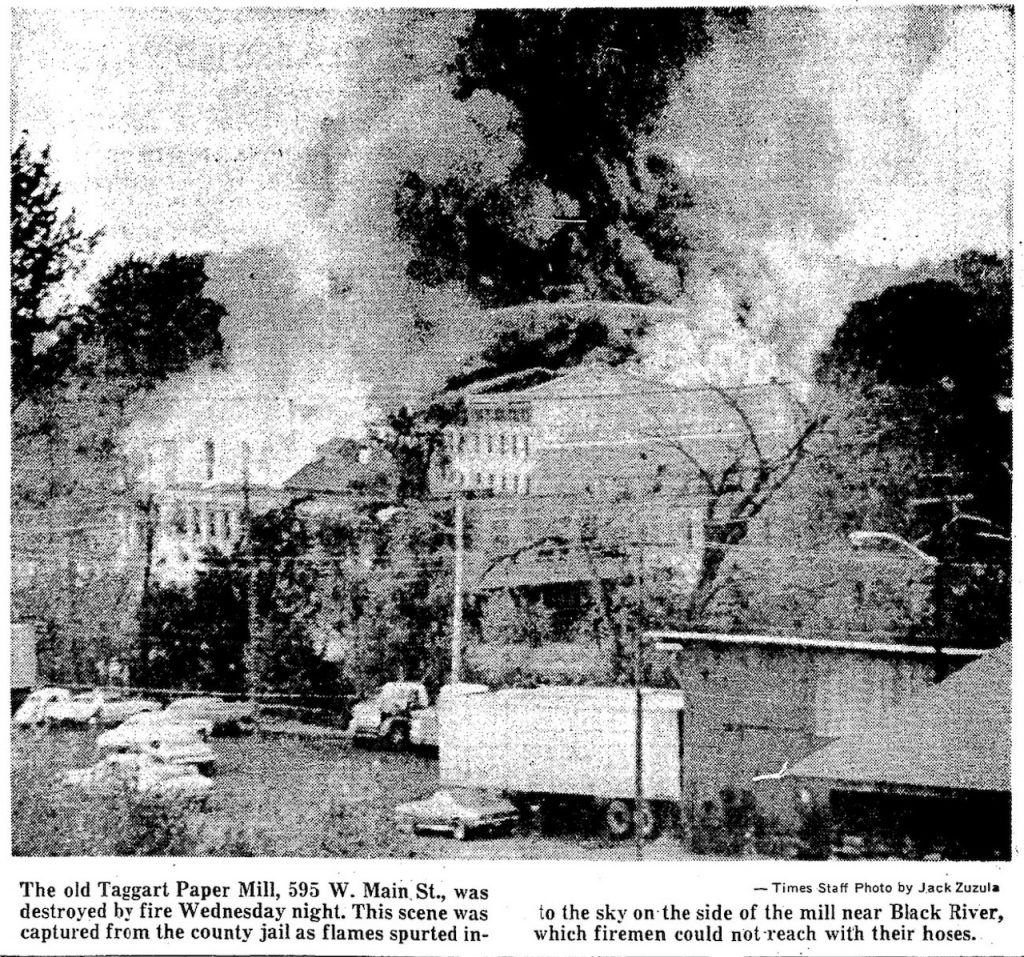

On October 4, 1972, a Wednesday evening, a fire destroyed the old Taggart Paper Mill. Fire and smoke could be seen for miles around and outside the city, drawing onlookers and requiring extra police to control traffic.

Per the Daily Times, it was a difficult fire to control—

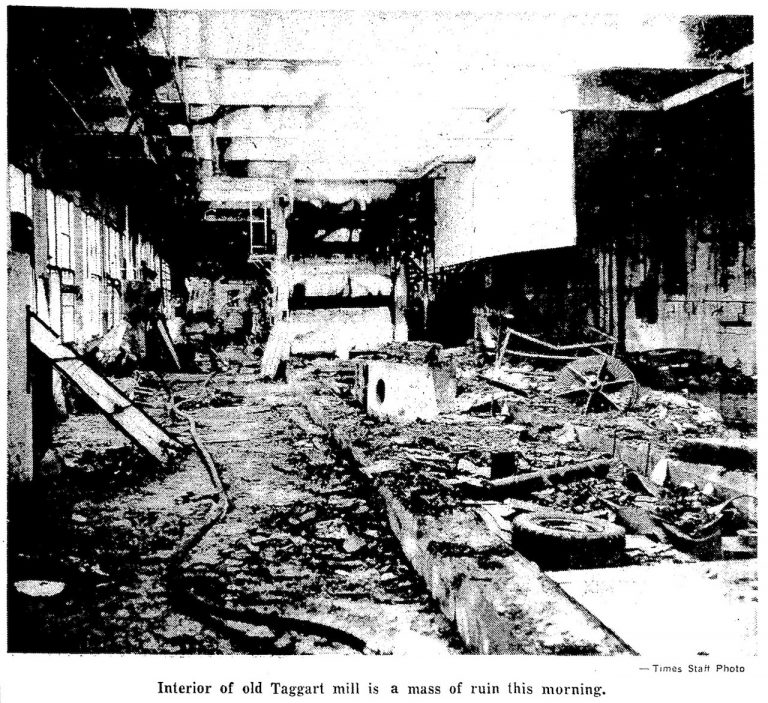

Firemen experienced difficulties in fighting the blaze because they could not reach the rear of the building which is on the Black River. As a result, the rear of the large building was completely burned and portions were toppling into the river late Wednesday night.

All city fire companies were alerted at 6:06pm.

Firemen had problems from the beginning, when the first truck on the scene — the city’s newest pumper — failed to work. Mechanics were called in as other companies were arriving.

Flames from the Taggart Paper Mill were reportedly leaping hundreds of feet into the air, with black smoke seen as far away as Brownville, Burrville, and Evans Mills.

Numerous other area departments would also respond, including the towns of Watertown, Brownville, and Glen Park, while two others, Calcium and Adams Center, were on standby at the Arsenal Street Fire Station No. 1.

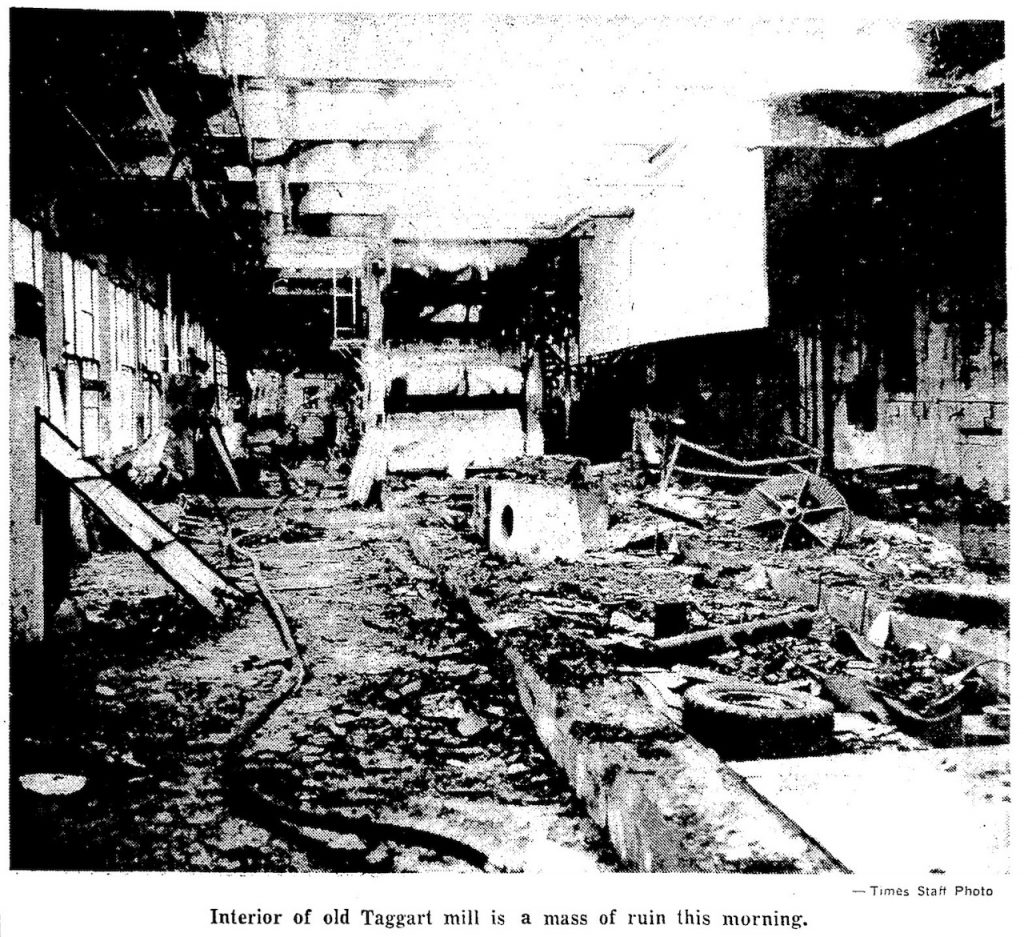

Also making the Taggart Paper Mill fire difficult was the reportedly oil-soaked, wooden flooring, a large quantity of paper (who would have thought?), and 80 tons of coal stored in a hopper. The fire would be brought under control around 9 pm, but firefighters were still dumping water onto the remains at 11 pm.

In June of 1973, the remains of the Taggart Paper Mill would be torn down, but the demolition job would become a topic of controversy and deemed incomplete by the city’s building inspectors.

In 1974, the city’s building inspectors would order the Black-Clawson Co., owners of the site, to complete demolition and secure the sight after they acquired the property from Taggart Paper Mill, Inc., Syracuse, formed by the late Abe Cooper. The ruins were deemed dangerous and a “death trap” for children by the city’s building inspector’s office, with “large unprotected sluiceways through which children could crawl, for fall, 30 feet to the rocks and water below.”

Per The Times June 4, 1976 article—

According to records filed in the building inspector’s office, inspector Richard J. Grieco received a telephone call Dec. 19, 1974, from Black-Clawson attorney Joel Feldman, who promised quick action on the building ruins but said his company was unaware of violation at the time of purchase.

After several attempts to remedy the situation after a fence that didn’t last through winter, the city would press Black-Clawson, stating that four years had passed since the fire and two years since Black-Clawson was notified of the existing issues. Black-Clawson would finally take action in July of 1976 to finish the job started by the previous owners. Per the Times, it would entail “breaking up the concrete floor, removing steel reinforcements, filling the excavated areas with tons of non-combustible material, and grading the site.”

The Taggart name had previously been associated with another large fire in Watertown’s history, that of the Taggart Block in 1919. Deemed the city’s worst fire since the Otis House fire in 1903, the Taggart Block fire would also face a number of issues relating to the fire department’s equipment failing as well, necessitating a steamer to be transported to Public Square by hand due to the unavailability of a horse and equipment failure.