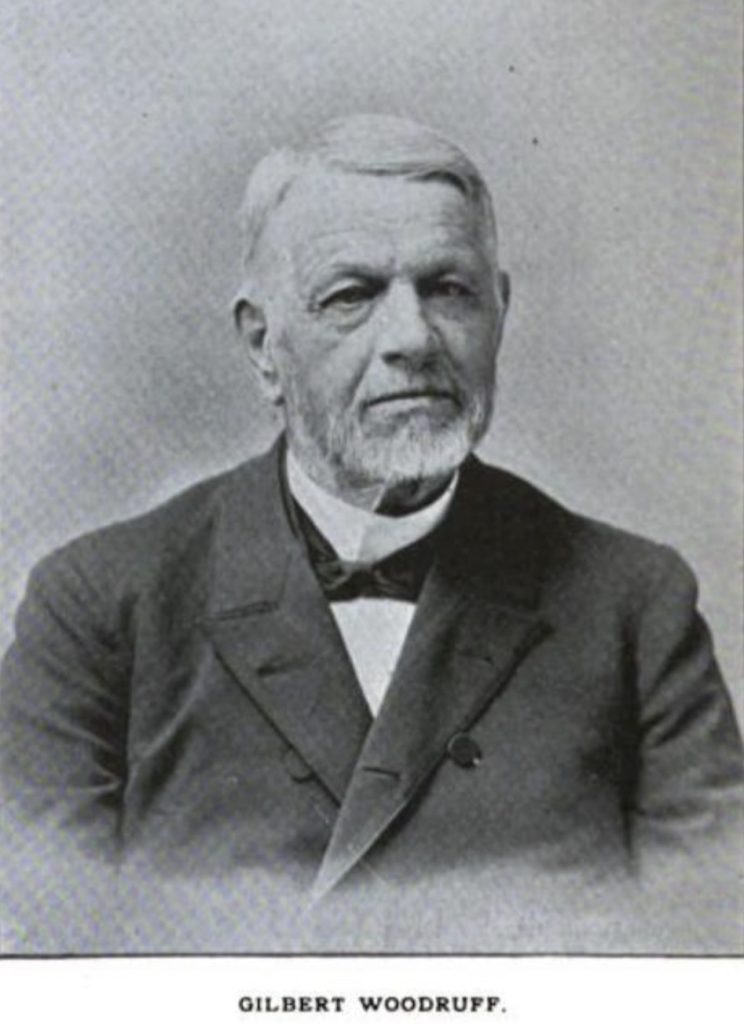

Gilbert & Walter Woodruff Build Washington Hall, Later Given To Y.M.C.A. By John A. Sherman

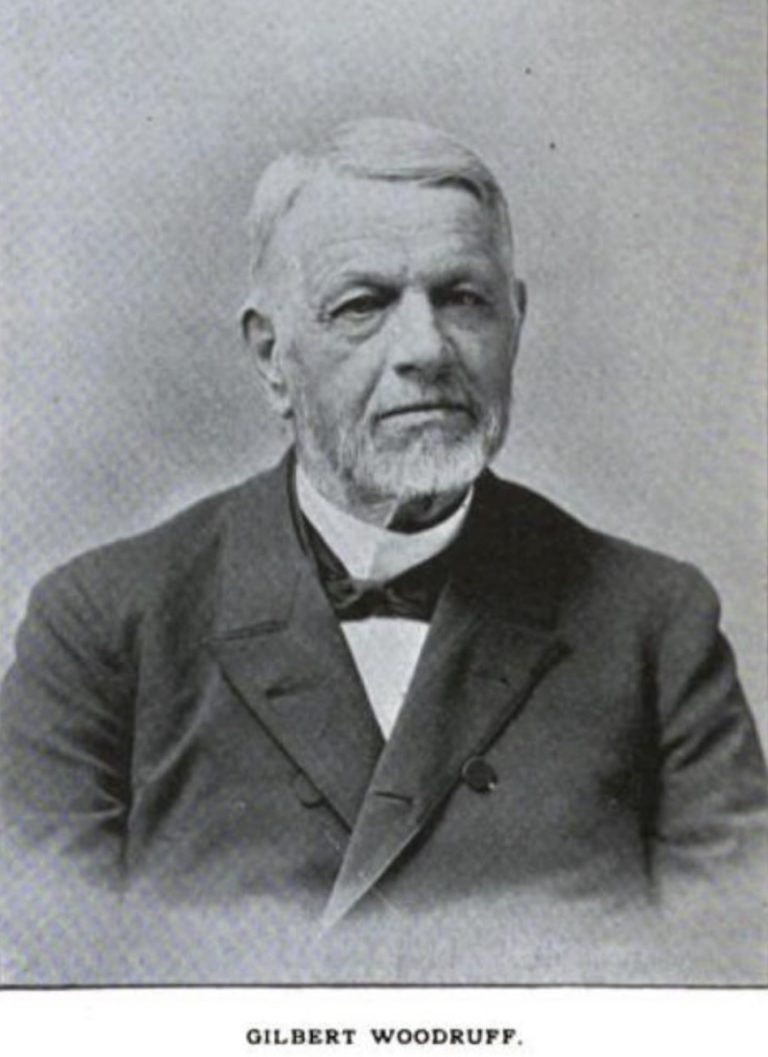

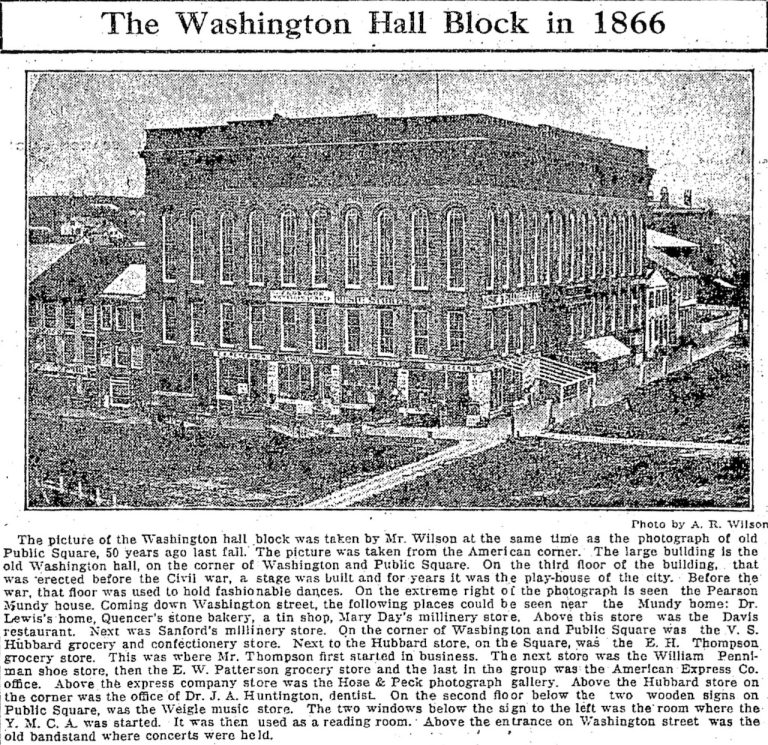

Back around the mid-19th century, before Washington Hall opened in 1853, the village of Watertown had few places for social gatherings outside of the church. One such place, Anthony Hall, located on Court Street, had been in use for some time, but the need for a larger facility was soon realized. Gilbert and Walter Woodruff, from a different, yet perhaps related, line of Woodruff descendants from Connecticut as Norris Woodruff, builder of the Woodruff Hotel, which opened two years earlier, would give the burgeoning village such a place with Washington Hall, considered amongst the finest in New York State at the time.

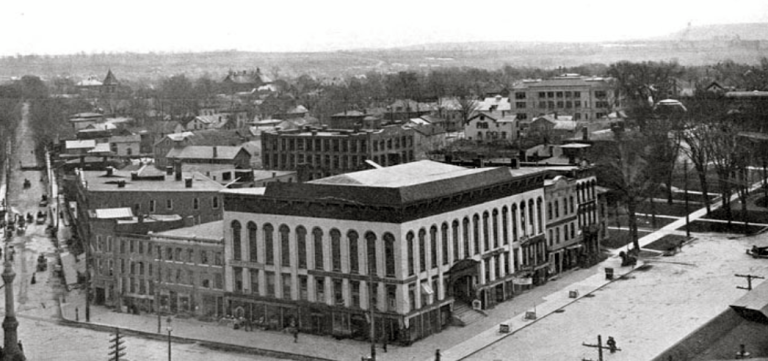

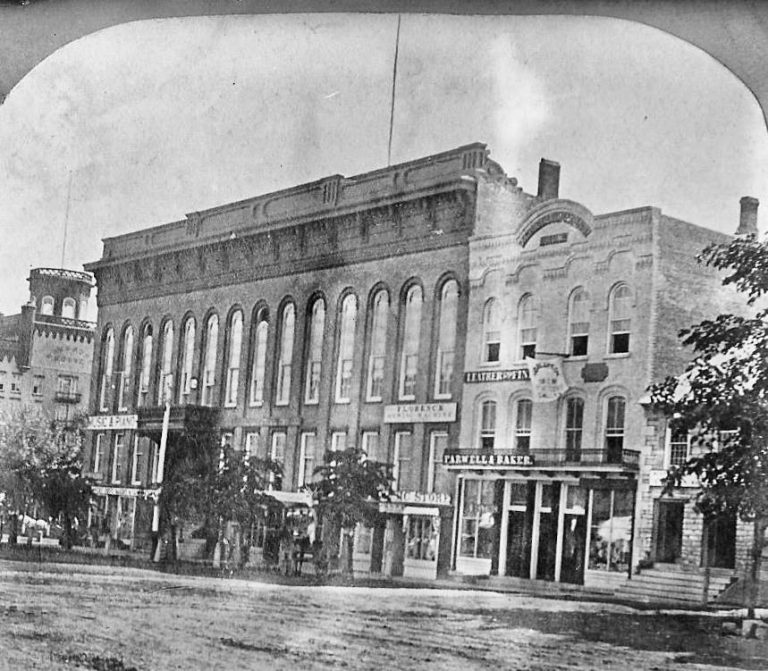

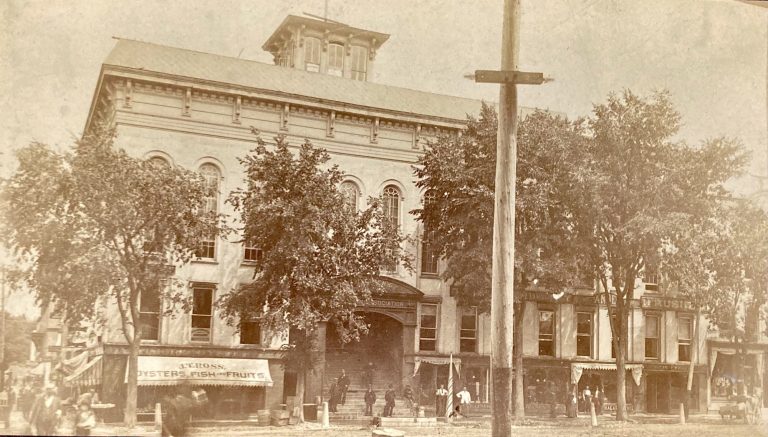

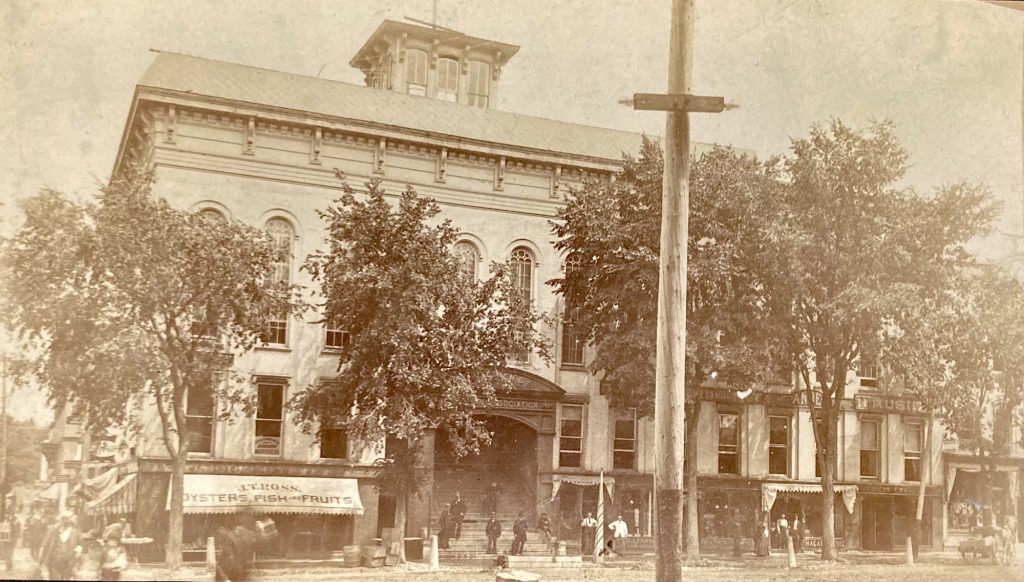

The site of Washington Hall was to be the location of the long-standing Public House, aka “Perkin’s Hotel,” on the corner of Public Square and Washington Street. The site had previously been occupied by the first brick building in Watertown, built by William Smith in 1806, comprised of two stories and a stone basement. Before Smith built upon it, the corner was the location of Zacharias Butterfield’s log cabin, he being one of Watertown’s first settlers.

Walter Woodruff, a builder by trade, had constructed several homes in the village and the town of Pamela, including the Solomon O. Gale House, a red brick building still on Thompson Street, home to the Sacred Heart Kindergarten school for some time. With the construction of Washington Hall, Walter and his brother Gilbert, who was assisted in forming his real estate business by Loveland Paddock, saw that Watertown had a facility with all the conveniences for large parties and public parties assemblies.

Upon its completion, The Northern New York Journal wrote in its Dec. 7, 1853 column–

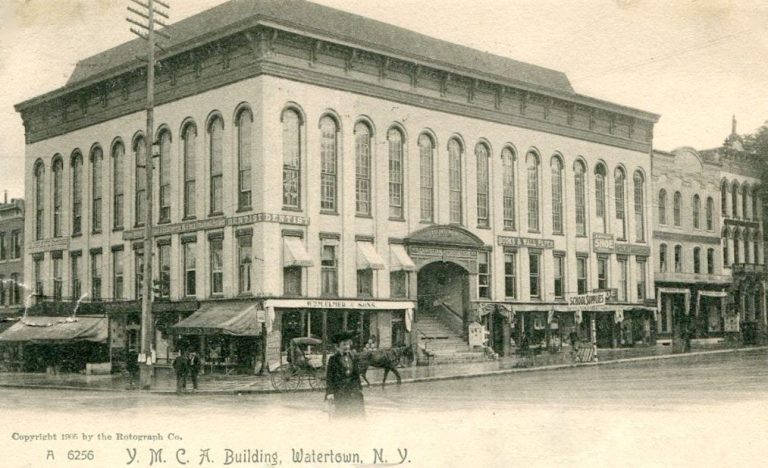

Washington Hall is 85 feet long, 64 feet wide, and 28 high. The walls are handsomely frescoed, and make a beautiful and grand appearance. It is lighted by five chandeliers, suspended from the ceiling, besides the lights about the platform or stage. On one side of the room there is a balcony-gallery, which will accommodate quite a number of persons. The whole Hall will seat some 1200. Some 160 can dance in quadrilles at the same time, conveniently.

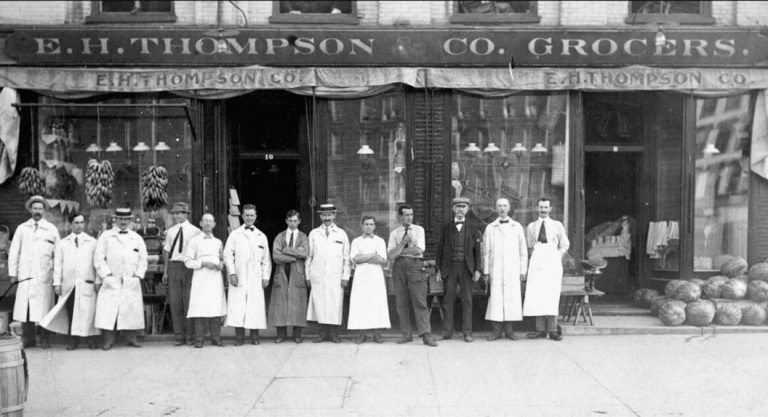

Indeed, the hall, particularly its second floor, was popular for dances, particularly waltzes, which were too numerous to mention. The first floor was home to numerous businesses over the years, some of which included the longstanding John Sterling Book Store, often seen in old photos of Washington Hall and Paddock Arcade, the E. H. Thompson Grocery Store, and the J. T. Ross Fruits and Oyster House.

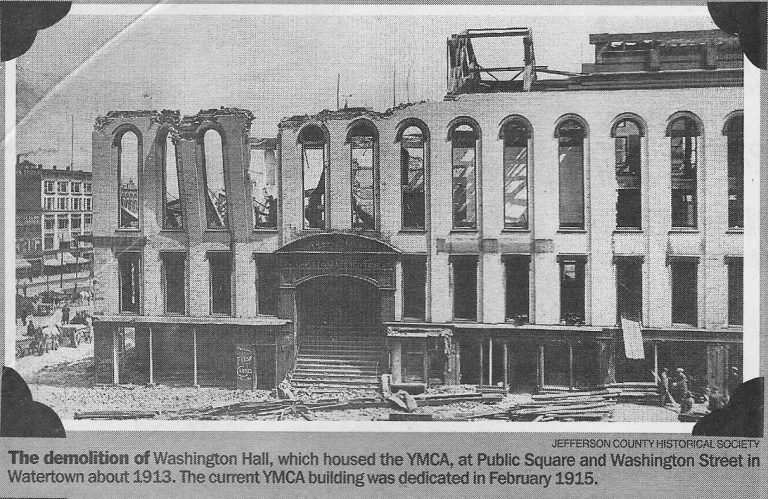

The second floor, at least in its early years, hosted a variety of activities, its first noted by a citizen’s letter to the editor of the Watertown Daily Times in 1913 when Washington Hall was in the process of being razed for the construction on the new Y.M.C.A. building–

As we have watched the falling of the bricks, during the leveling of dear old Washington Hall, many pleasant incidents of almost sixty years ago have crowded upon our memories.

How well we remember the first entertainment of importance held there, by the pupils of Jefferson County Institute, March 24, 1854. With how much pride, satisfaction and enthusiasm we entered its doors for the first time. The place was grand enough for a palace then. How readily we recognized the busts of Washington, Clay, Calhoun and Webster. Then every school boy and girl knew much concerning those illustrious characters. Our greatest ambition was to imitate their style and finished speeches. Now our school systems has forgotten their examples.

The program referenced in the letter was so long that it required morning, afternoon, and evening sessions.

Arguably the most popular events were lectures from the great orators of that era, though, in later years, the facility was the home court for the Watertown High School basketball team. The younger John Sterling, the grandson of Micah Sterling, wrote of the many speakers to visit Washington Hall. Orators such as John B. Gough of London and a temperance speaker, who drew over 1,000 when there was standing room only at a time before building codes dictated occupancy rates. Wendel Phillips, William Morely Puncheon, and Henry Ward Beecher were other speakers remembered, most of whom were paid between $250 and 300 a night.

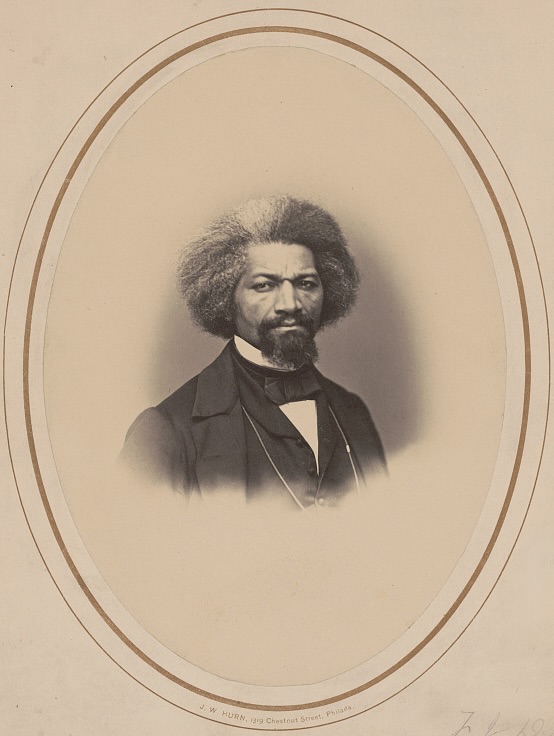

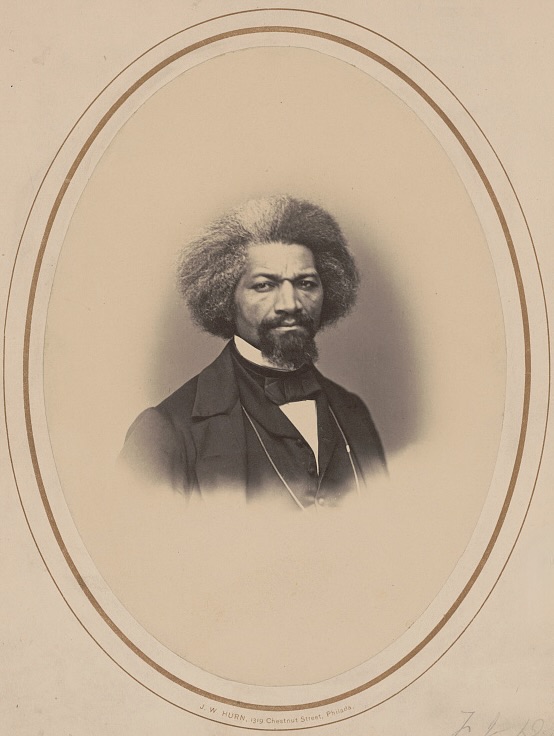

Perhaps the most notable of all speakers was Frederick Douglass, who visited during the early fall of 1855 to discuss the abolition movement and race issues in front of a large crowd. The New York Reformer reviewed his appearance, writing, in part–

His meeting here in the evening, was one of the largest that have ever graced Washington Hall. Mr. Douglass, as an orator, met the highest anticipations of his audience; as a man of dignified appearance, rational views, massive though acute intellect and pleasing address, he won a more favorable opinion than had preceded him.

For an hour and a half he held the audience in profound attention, except when bursts of applause greeted his pointed remarks—He presented in a bold and original light, the wrongs of the institution of slavery—the power that the slave oligarchy exercise over the churches and political parties of the country.

He illustrated the subserviency of doughfaceism by a very striking, though most humiliating comparison. He said the South and North might be compared to a master and his dog. The North want offices, and the South have them to sell for a vote in Congress. The master taking a bone (office) from his pocket, calls (imitating with his lips the call of a dog) and the obedient canine comes cheerfully forward.

Holding out the bone, the master says, speak—and the dog speaks; stand up—and he stands up in prayerful attitude; now roll over—and he rolls over; now go and lie down—and he goes and lies down, while the imperious master puts up the bine in his pocket.

One of the most eminent professional men remarked the next day, that “he was never so humiliated in his life, to be told such palpable truths, by a negro, in so sarcastic a manner; yet that there was no way of escaping the truth and force of the illustration.”

He dealt, as but few speakers can and hold the attention of miscellaneous audience, largely in first principles, natural justice, and the cardinal principles of Christianity. Many passages of his address were sublime, many thrilling, and the whole was truthful and pertinent.

Unfortunately, Douglass’s next visit to Watertown and an attempt to get a room at Hotel Woodruff wasn’t as pleasant an experience. Initially, he was denied a room by the hotel’s manager due to his color. The manager eventually stated he would give Douglass a room but that he would have to eat his meals in it. Douglass refused the offer, and according to Douglass’s letter to the editor, an unidentified man in Watertown graciously accepted him as a guest in his home.

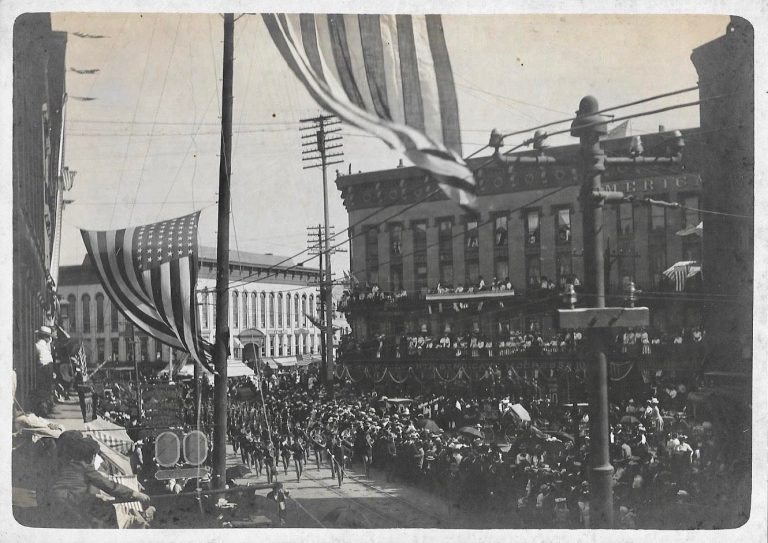

After the assassination of President Lincoln in 1865, like many other buildings on Public Square, Washington Hall was draped in black. A funeral procession was held in the village, lasting nearly an hour and ending where it began, at Washington Hall.

One of Lincoln’s favorite actresses whom he had seen perform numerous times, Maggie Mitchell, performed at Washington Hall in the 1870s. Ironically, it was said that she was friends with John Wilkes Booth. In a Watertown Daily Times piece published March 23, 1918, shortly after her death at age 81, former Congressman Charles R. Skinner recounted her performance here–

“I remember it as well as though it were last night,” said Charles R. Skinner today. “I was never moved by a play as I was by Fanchon with Maggie Mitchell. She was the greatest emotional actress of her time, and she had the audience continually laughing or crying. I later met her at the Woodruff.”

Brittanica.com further discussed Maggie Mitchell’s fame and work–

Her characterization of the sprite of a heroine, which included a graceful and entrancing shadow dance, was an immediate sensation. Her Southern tour was cut short by the Civil War, and Mitchell took Fanchon to Boston and New York, where it was equally successful. Fanchon remained her mainstay for 30 years.

Audiences never tired of it—her admirers included the likes of Abraham Lincoln and Ralph Waldo Emerson—and even in her 50s Mitchell retained the winsome, elfin appeal that made her so successful. She also early obtained the rights to Fanchon, which enabled her to amass a considerable estate. She occasionally played other roles, as in Jane Eyre, The Lady of Lyons, Ingomar, and The Pearl of Savoy. After a final performance in The Little Maverick in Chicago in 1892, she retired from the stage.

About the time Maggie Mitchell performed at Washington Hall, John A. Sherman, uncle to one of the North Country’s most colorful characters, Huckleberry Charlie, donated a portion of the block to the Y.M.C.A. Before long, the organization grew rapidly and took over the second floor of the building. At the tail end of the decade, another performer with ties to Lincoln’s assassination would star at Washington Hall.

During this era, it was customary for the old city band to give a series of concerts each winter at Washington Hall. As was told in the Watertown Daily Times retrospective piece on April 4, 1919, “Some one thought of Nick Goodall one winter and went up into St. Lawrence county to have him come down and play at one of the concerts. After much persuasion he was brought here and advertised extensively.”

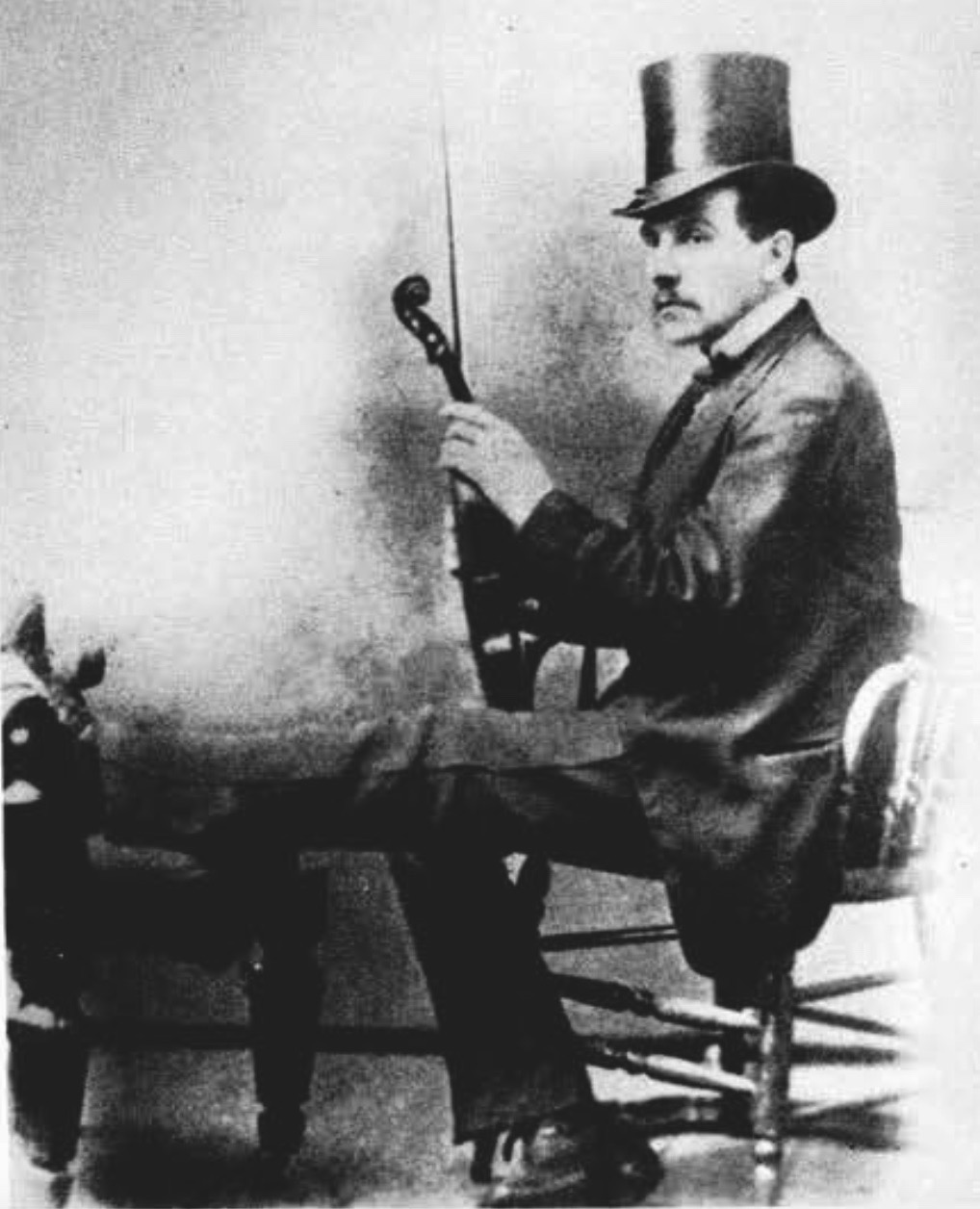

Nick Goodall was an immensely talented fiddler whose father, J.K. Goodell, was a professor, cello, and violinist who happened to be scheduled to play at Ford Theater the night of Lincoln’s assassination. Much has been discussed about the incident and Nick’s upbringing, and how he, unfortunately, died a pauper at the Jefferson County Almshouse between the ages of 30 and 40 just two years later, much of it from writer Irvin Belcher in a Watertown Daily Times 1936 column which can be found via the link on the county almshouse above. The Watertown Daily Times would say of his performance at Washington Hall–

A very high-toned and cultivated audience assembled at Washington Hall on Saturday evening to hear the violin and piano music of the phenomenal Nick Goodall. The result was that everybody present enjoyed a very fine musical treat. Nick played a very choice program, and one that could not help suiting a variety of tastes.

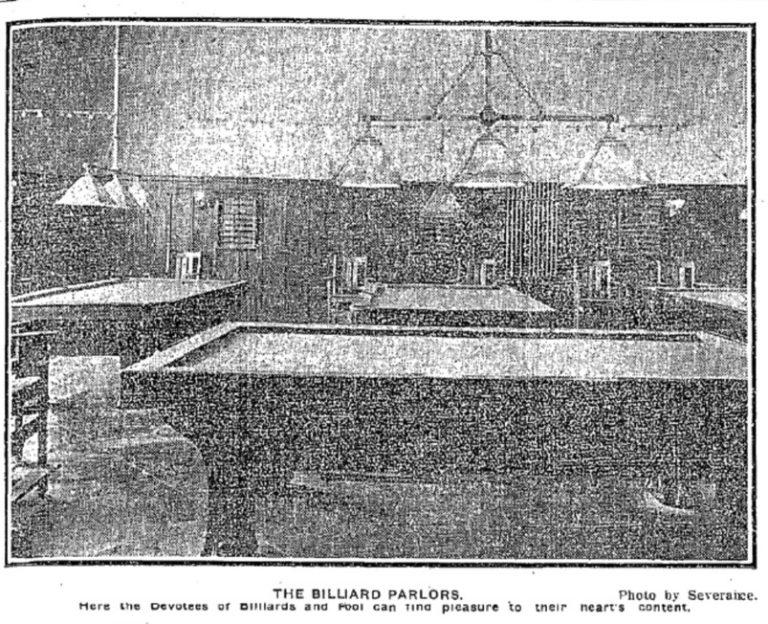

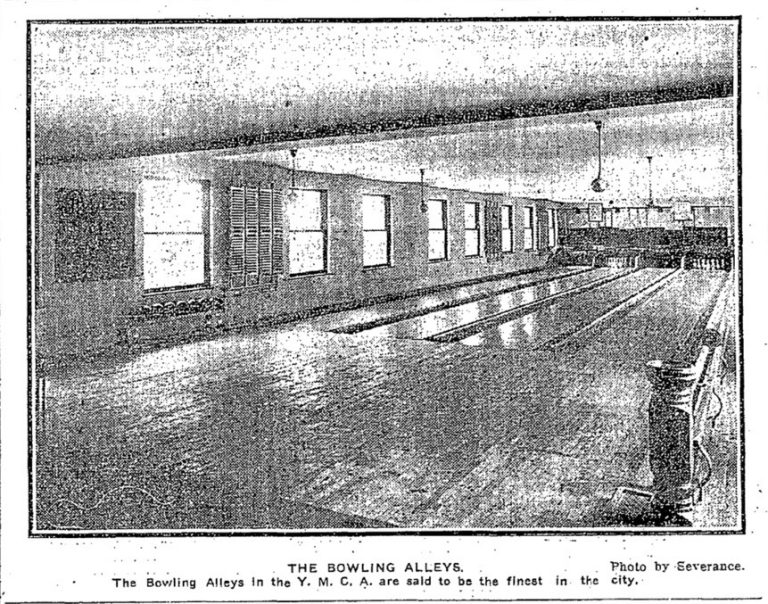

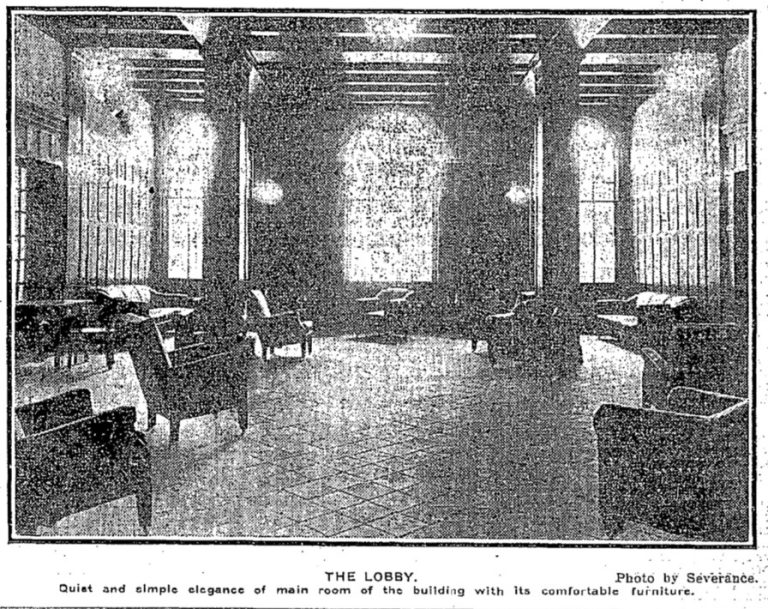

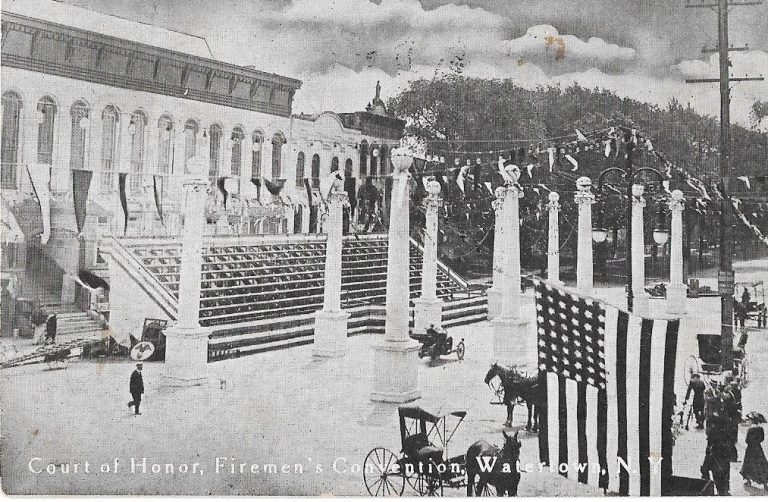

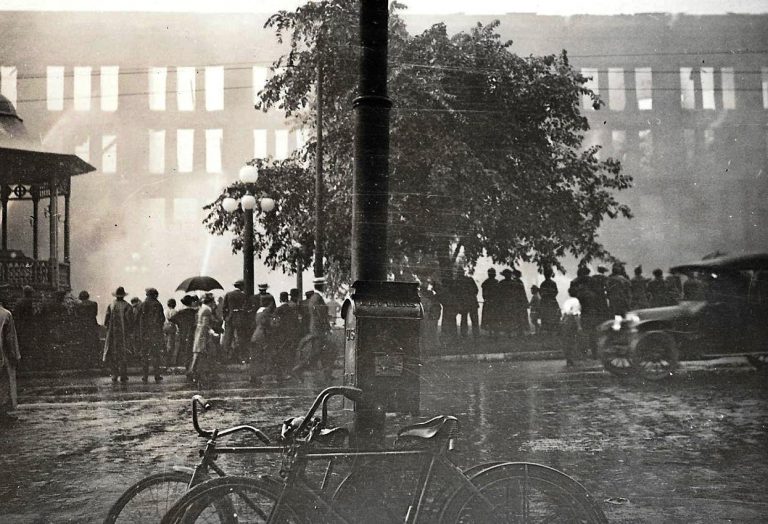

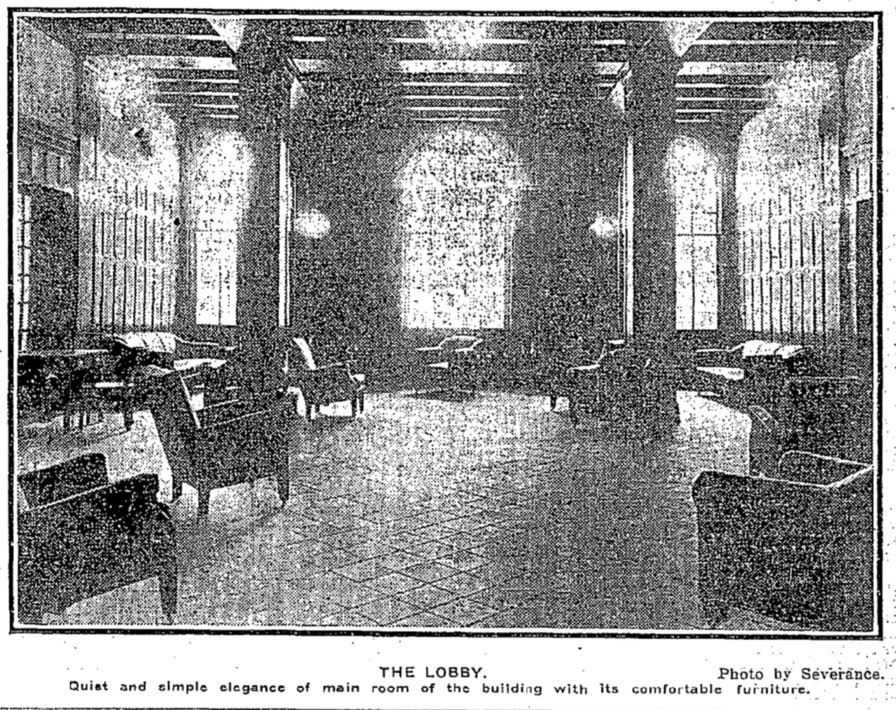

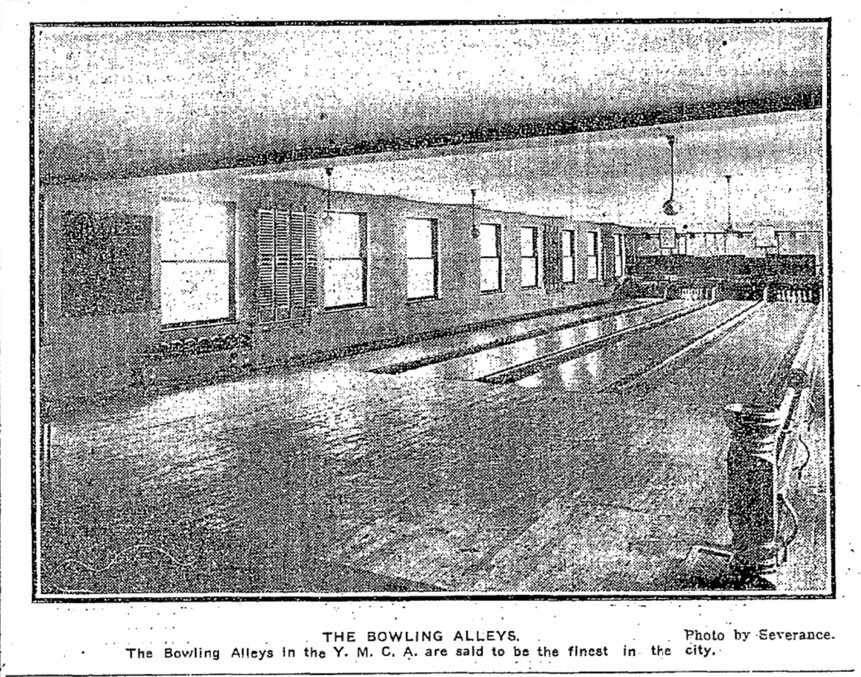

As the Y.M.C.A. continued to outgrow its space, Washington Hall having become known as such, it became necessary to plan for the future and construction of a new facility. In 1912, a building campaign began, which raised $163,000 to build the current Y.M.C.A. Building.

During the demolition of Washington Hall, workmen uncovered a “scene,” interpreted as a mural, painted on the south wall of the building depicting the Black River Falls. A Times article dated April 28, 1913, noted, “It is on the south wall of the building and stands where one of the side walls of the gymnasium floor was later placed,” and that it was the first time anyone had seen it for about 40 years.