Emory Van Schaick Disappeared in October 1884. His Unexpected Reappearance in 1885 became a Morbid Spectacle.

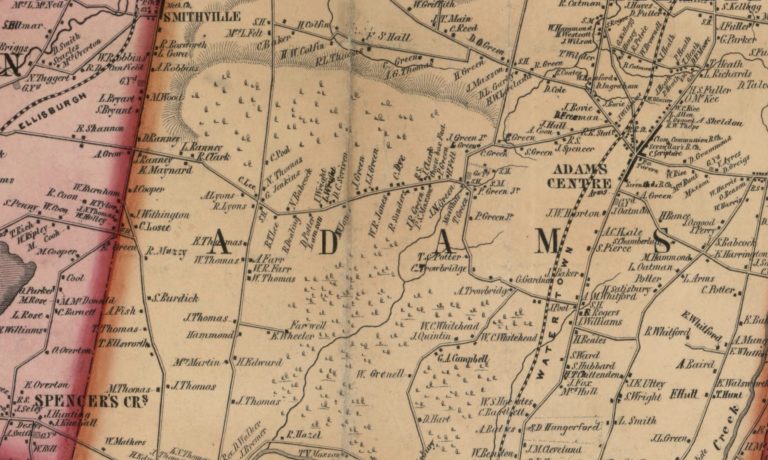

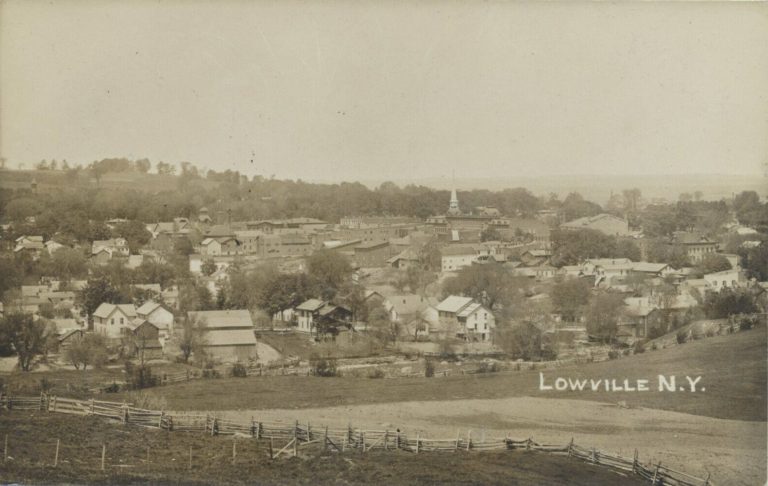

Emory Van Schaick became the subject of one of the more unusual and ghoulish stories in Northern New York when the 20-year-old disappeared from his employer’s home about midway between Adams Centre and Smithville. Van Schaick, whose name also appears as Emery E. VanSchaick, was the youngest of four sons to Henry and Catherine Romang Van Schaick, who also had three daughters. He was last seen on October 8, 1884, before abruptly departing for the Midwest.

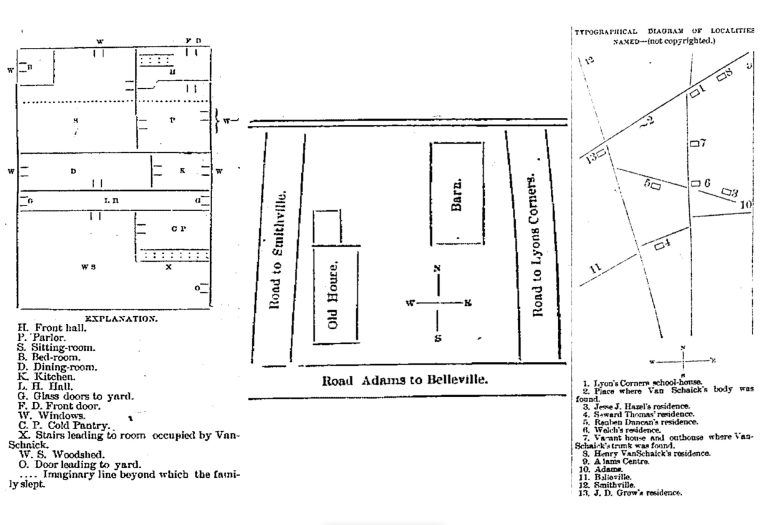

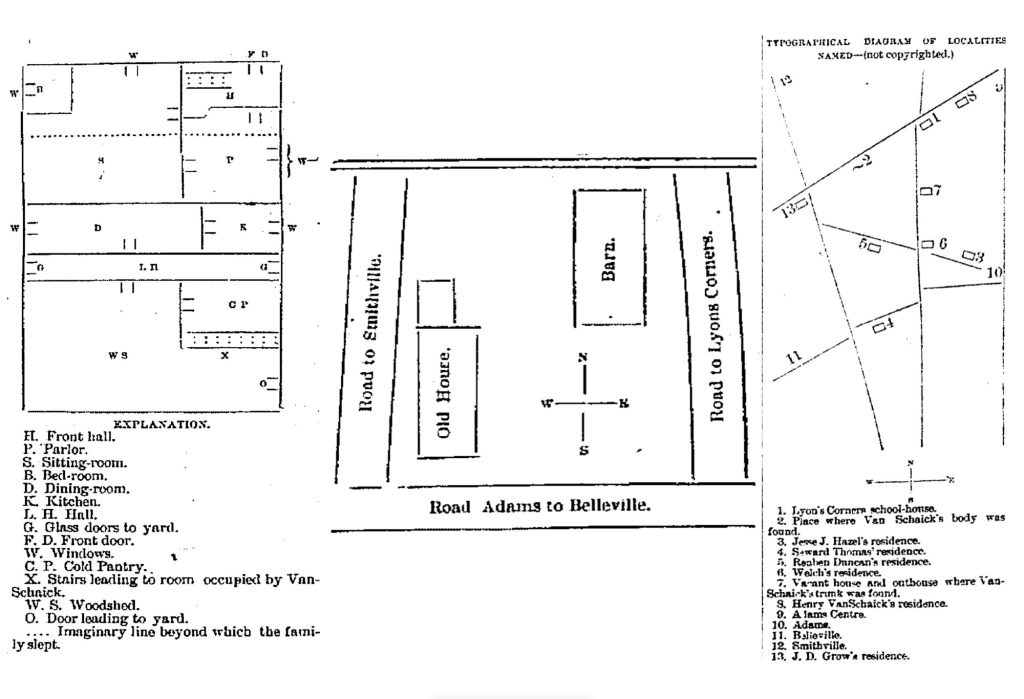

About ten years prior, the Van Schaick family moved to a house near Lyons Corners. Considered poor, the father and sons farmed in the neighborhood, and the daughters supported as they could, one teaching at the nearby Lyons Corners school.

Emory, a hard-working and respected young man, had taken up residence at Seward Thomas’s farm, working there as needed and elsewhere when he could. The house, built in 1800, was the first frame house in the Adams area and was lost in a fire in 1948. Before Van Schaick’s disappearance, he had traded a horse, buggy, and harness with Arthur Duncan, a nearby neighbor who was two years older, for a watch valued at $55, a ring at $12, and a note given by Duncanor $35, before retiring for the evening.

The next morning, the Thomas family arose as usual to start the day’s work, but Emory was nowhere to be found. After waiting for him to help milk the cows, other workers set out to find him. His room was empty, and his trunk was gone. The workers then gathered a search party and scoured the nearby woods and swamps but could not find any trace of Emory. Suspicions quickly centered around Arthur Duncan, the last person seen with Van Schaick.

As the Watertown Daily Times printed in its May 13, 1885 edition—

Duncan told a very straight story and intimated that Van Schaick had become involved in “some girl scrape” and had “lighted out.” He averred that they might look the woods through and that they would find nothing of Van Schaick. This story seemed reasonable and the search was abandoned, although the missing man’s mother was not satisfied regarding her son’s disappearance.

This would explain Emory and his trunk disappearing (light out, meaning to leave in a hurry), but it was not like him to do so. More questions arose. Where did he go? Why did he leave without telling anyone? Several days later, his trunk was found in the outhouse of an unoccupied tenement owned by Vincent Far. Some of Van Schaick’s finest clothes and other apparel were inside, raising more questions.

Almost as soon as the trunk appeared, word from Emory came in the form of a telegram from Syracuse to his father requesting that it be forwarded to Sturgis, Michigan. Emory’s sister, Mary Catherine Van Schaick Witherby, and the trunk sent a letter to the same Michigan address. Both remained unclaimed after a reasonable period, sparking speculations that Emory was headed further west as no further word was heard from him. Then, there was a gasp on a cold May day, with the snow finally retreating from its long winter slumber in Northern New York.

The Watertown Daily Times reported in the same May 13th edition—

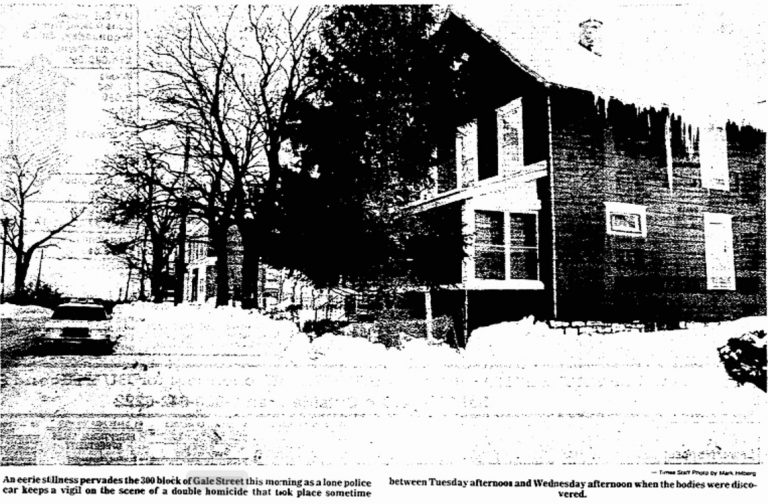

During the schoolday yesterday, the children in attendance at Miss Van Schaick’s school at Lyons Corners went to the swamp, about a half mile away, to look for wild flowers, and while playing about the fence on the edge of the highway, Everett Farr and others discovered the body of a man under a pile of brush, near the fence. They spread the news of their discovery and people began flocking to the spot. Among others who went was Miss (Carrie) Van Schaick, who was terribly startled to recognize the clothing and other marks, the body of her brother.

The body was placed on its face, bootless and hatless. The feet were clothed with a pair of blue woolen socks. The coat was originally of some light, finely checked material, and it is said the trousers to match are now among Emory’s effects.

On the skull which has been denuded of flesh is a hole under the left ear, several seams or cracks extending from it in various directions, showing plainly that the fatal blow must have been given a slung shot or some other hard, blunt weapon.

District Attorney Emerson was busy all day with sessions at court, but once informed of the body’s discovery, telephoned Deputy Grommons of Adams and had Arthur Duncan arrested on suspicion of murder, despite only circumstantial evidence. Duncan, who had married Alta Hazel only a few months ago, protested his innocence. Coroner Rexford was unable to attend to the body until the following morning. As a crime scene, it would be guarded by lantern light vigil overnight. When Emerson and Rexford arrived the following morning, they were greeted by quite a morbid scene.

As a Times reporter wrote in the May 14th edition—

Arriving at the spot where the body was discovered, and where it had lain undisturbed since that time, a curious spectacle presented itself to the reporter. Hitched along the roadside were thirty-seven vehicles of different descriptions, from all parts of the country adjoining. One was from Evans Mills, one was from Texas, Oswego County. Sandy Creek, Adams, Smithville, Adams Centre and other villages were represented. Fully 350 men, women and children gathered about the spot where the slowly decaying remains, thawing under the influence of the warm sun, began to emit anything but an agreeable odor.

Young men climbed trees in the immediate neighborhood that they might obtain a better view of the proceedings. Young women pressed forward on the brush heaps, almost directly over the body, and, while they applied their handkerchiefs to their nasal organs, looked long and curiously at the disgusting sight, and seemed loth to leave it. As an example of morbid curiosity its like has never seen in this county.

Drs. Low and Bailey made a brief examination of the remains, the ghoulish details written in the same Times article—

The body was in an advanced state of decomposition. A portion of the scalp still clung to the skull, which was frightfully fractured. The brains, viscera and internal organs were gone. The left arm and hand and the left leg from the calf to the foot, were the only portions to which the flesh adhered, and these gave evidence of being eaten and gnawed by carnivorous animals. The skin on the palm of the hand was loosened and hung from the end of the fingers. The nails were ready to drop off at the least jar. It is probable that both the leg and arm had remained longer under the snow than the other portion of the body.

Also included was evidence of ten heavy blows, rendering the skull crushed, thirteen pieces driven inwards. Several teeth, including gold-filled incisors, were found nearby. Despite the conditions of the remains, there was little doubt by the recognized clothing and the approximate height of the body that it was Emory Van Schaick. Furthermore, with the Inquisition well underway, there appeared to be little doubt that his murderer was Arthur Duncan, with Mrs. Alta Duncan being the common denominator.

The Inquisition was held in May 1885, and most of the testimony was printed in the Watertown Daily Times. Much was made about the telegram(s) supposedly sent by Emory from Syracuse. On a separate occasion, Mrs. Ella George Graham of Black River received a telegram on October 16th asking her to come to Sturgis, Michigan. At the time, Ella Crane was a resident of Evans Mills and received much attention from Emory Van Schaick. His affections stopped after she “treated him so cooly,” perhaps already involved with her future husband.

Others were asked to identify the signature on the telegram as authentic or that of Arthur Duncan. Nobody could. However, one witness testified to the connection between Emory Van Schiack, Arthur Duncan, and Alta Hazel. The Times reported on May 18, 1885—

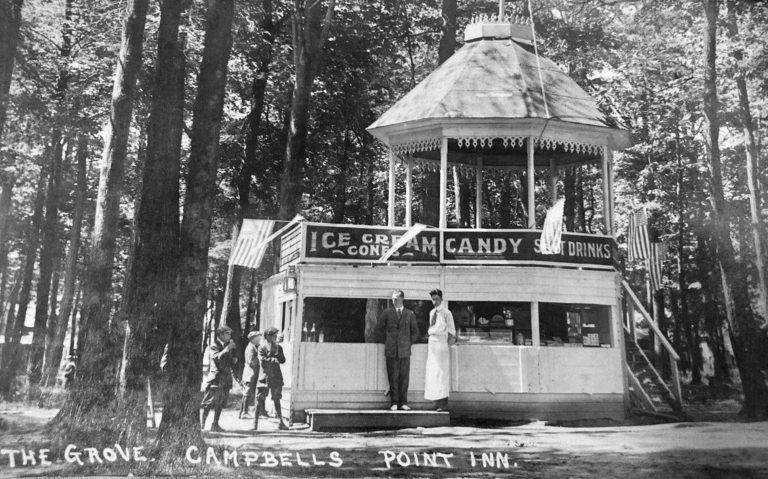

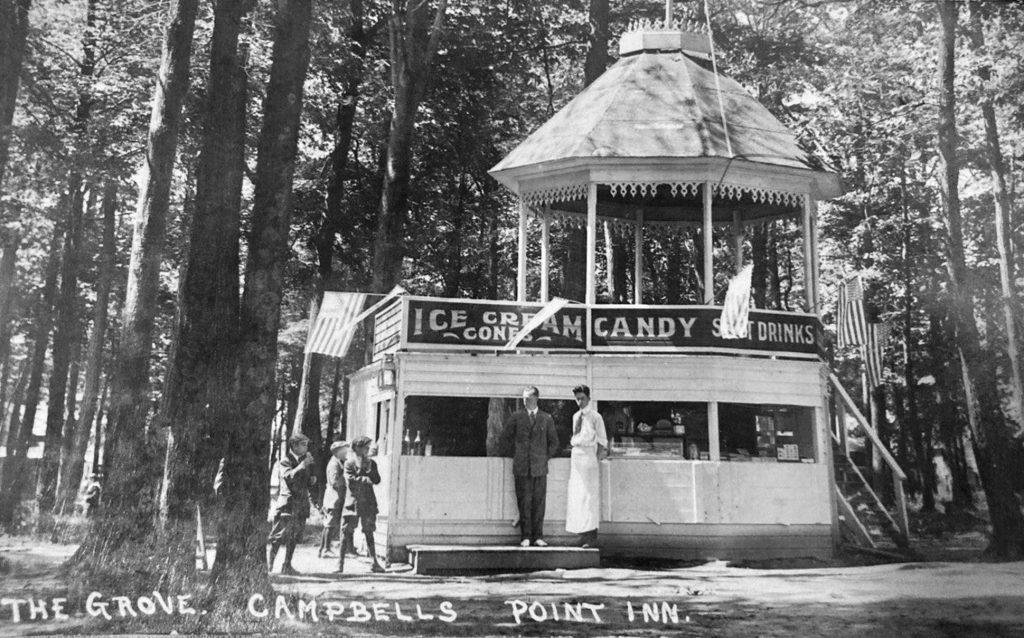

Darius Potter testified that Van Schaick and Duncan both went to Campbell’s Point Picnic with dates. Duncan paid some attention to Miss Hazel, Van Schaick’s date, and Van Schaick appeared not to like it; at the request of Miss Putnam, I told Duncan not to do it; he said he didn’t know what difference it made whether it stopped or not; told him he ought to stop, and he did.

The testimony of M. John Clark stated that Duncan had spent the summer working for the Hazels and had become acquainted and preoccupied with Alta. Smith H. Ketchum’s testimony had Arthur and himself aboard a train about ten days after Van Schaick went missing. According to Smith, Duncan got aboard the train in Adams, paying the fare to Sandy Creek and Richland.

At Sandy Creek, he intended to telegram Van Schaick but supposed he could do it just as well at Richland. He then offered to pay Smith’s way to Syracuse and back, with Smith being acquainted with Van Schaick, whom he wanted to talk to. Smith declined but told Duncan he might be better off going to Rome if he couldn’t find Van Schaick, as his uncle lived there. Smith departed the train in Pulaski, but the trip to Syracuse puts Duncan there about when the telegrams were sent.

Joseph J. Williams provided more incriminating testimony, printed in the May 19 edition of The Times—

Was on the band excursion down the river; saw Van Schaick on the excursion; asked him where his girl was; he pointed out a young lady and said, “there’s my girl;” at luncheon he ate with her; he said it was a Hazel girl; saw Mrs. Hazel there (Alta’s mother); heard Duncan say there was no use looking in the woods for Van Schaick.

Next was Alta Hazel Duncan’s Testimony—

I was acquainted with Emory Van Schaick; first knew him sometime in the spring of ’84, when he came to Mr. Hazel’s; I lived there; while he was there he took me to Campbell’s Point to a picnic; did not wait on me other than that; he was in my company on an excursion once; he drove to church once; I went with him; I went with him one evening to his home; he did not visit with me separately from the rest of the family; didn’t understand that he was my suitor; first knew my husband sometime last summer.

(I) was not intimately acquainted with him at any time before Van Schaick left Hazel’s; went down the river with him once before Van Schaick left; think it was on the Mannsville excursion; Van Schaick went to the excursion; after Duncan went to Mr. Hazel’s he waited on me; it was some time after he went to Hazel’s that I understood he was my suitor; it was three or four months after; it was January sometime; was at Mr. Hazel’s on Oct. 8; do not know what time Duncan came home; went to bed usually at 9 o’clock.

Surprisingly, many young women attended the Inquisition, which ended on May 28th with a telephone statement from Sturgis, Michigan. Eri Faber swore that his son corresponded with Arthur Duncan that spring in Sturgis, Michigan. The case was submitted to the jury at 3:10 p.m. Though Duncan was not part of the Inquisition, he spoke to a Times reporter. The short interview, published in early June, shed no new light on the murder other than Duncan claiming Emory to have made several potential enemies by “being sharp.” Duncan otherwise maintained his innocence.

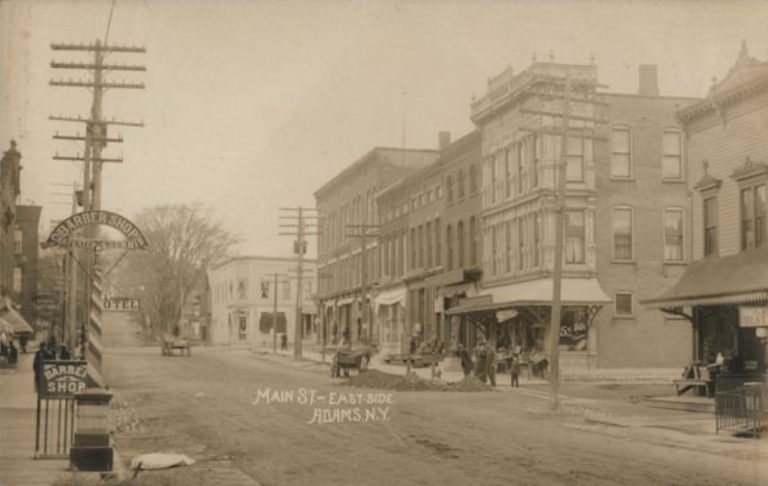

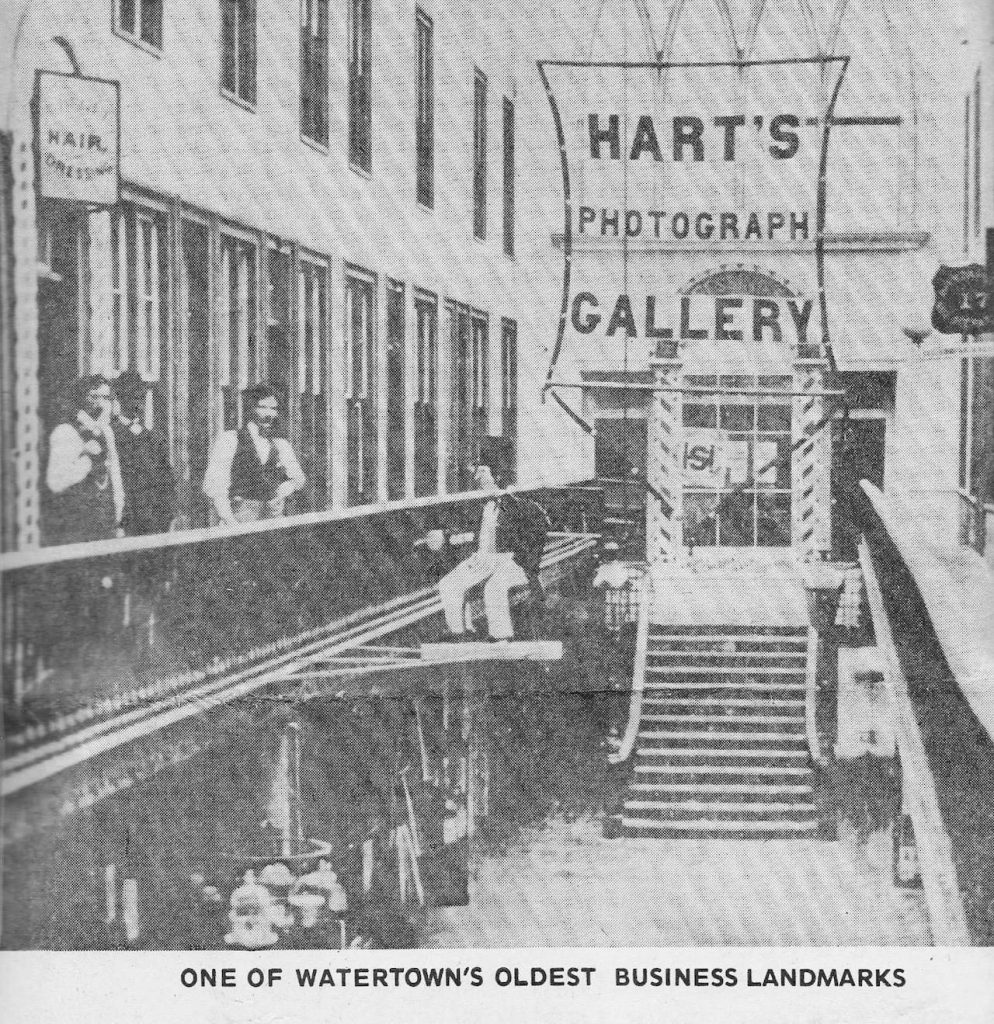

The trial began on February 16, 1886, at the Jefferson County Courthouse and lasted over two weeks. Eighty-seven witnesses were sworn in for the people and 17 for the defense. Attorney Wilbur F. Porter, a six-time mayor of Watertown, represented the defense. The Watertown Daily Times’ reporting was exhausting, with 59 columns published by May 6. After four hours of deliberation, the verdict came back: guilty of second-degree murder, which carried a sentence of life imprisonment despite only circumstantial evidence.

Attorney Porter had presented the doubts within the case effectively, questioning any jealousy on Duncan’s behalf regarding Van Schaick’s pursuit of Alta Hazel, with whom he was believed to have had the upper hand. He also presented the case as involving two friends, not rivals. As a result, the jury was split on the charge of first-degree murder, saving Duncan from capital punishment. But the story didn’t end there.

After serving 20 years of a life sentence with hard labor at Auburn, Arthur Duncan petitioned Governor Higgins in 1906 for a pardon. Higgins consulted with Judge E. C. Emerson, the district attorney during the trial, but Emerson was “unfavorable” to the notion. A year later, District Attorney Pitcher and other area attorneys inquired at Auburn about Duncan. It was reported the prisoner was well-behaved and believed to be losing his eyesight. A month later, after spending half his life in prison, a 42-year-old Duncan was granted a pardon.

No further information was found regarding Duncan’s life other than that he settled in the Auburn Area.

In a strange twist, while covering a July 27, 1891 story of a clairvoyant in the Utica area, the Watertown Daily Times briefly mentioned the Van Schaick case—

A man disappeared very suddenly from his home and friends near Watertown. A detective was employed to look him up and he came to Utica and visited Mrs. Light (a known clairvoyant.) She consulted with her “unseen friends” and reported that the man had been murdered, that his body was concealed under a brush heap and she described the murderer. Within six months from that time the body was found and Arthur Duncan is now serving a life sentence at Auburn, convicted on circumstantial evidence of killing Emery (sic) Van Schaick at Smithville.

Mrs. Light’s revelations played no part in the case, however, and the discovery and conviction would have resulted had she never been consulted.