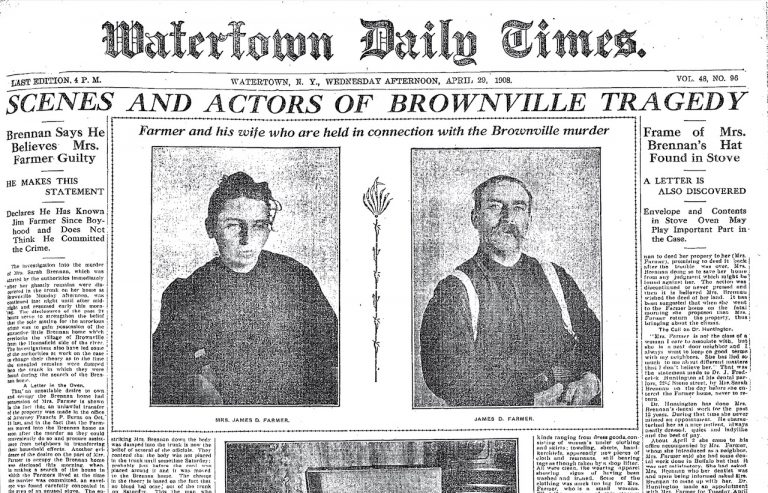

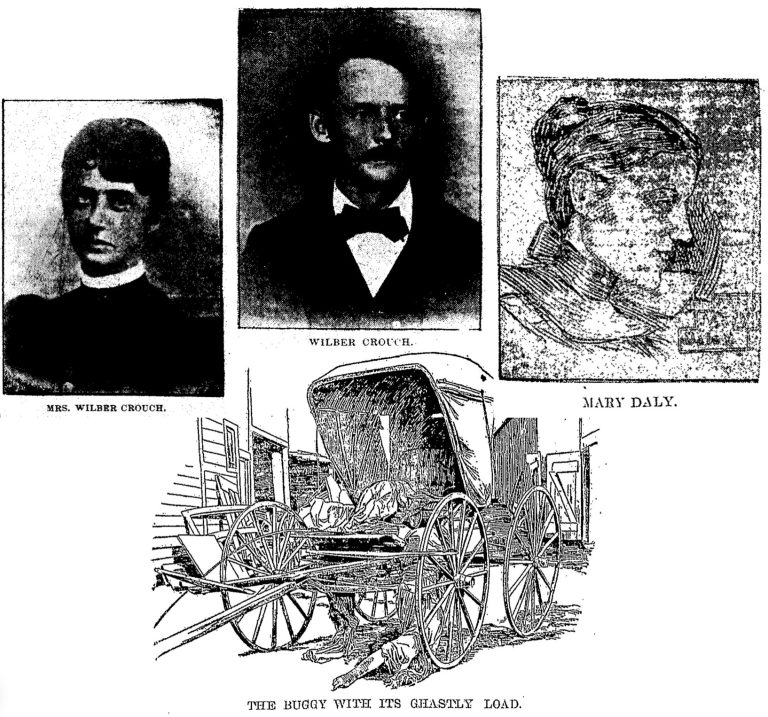

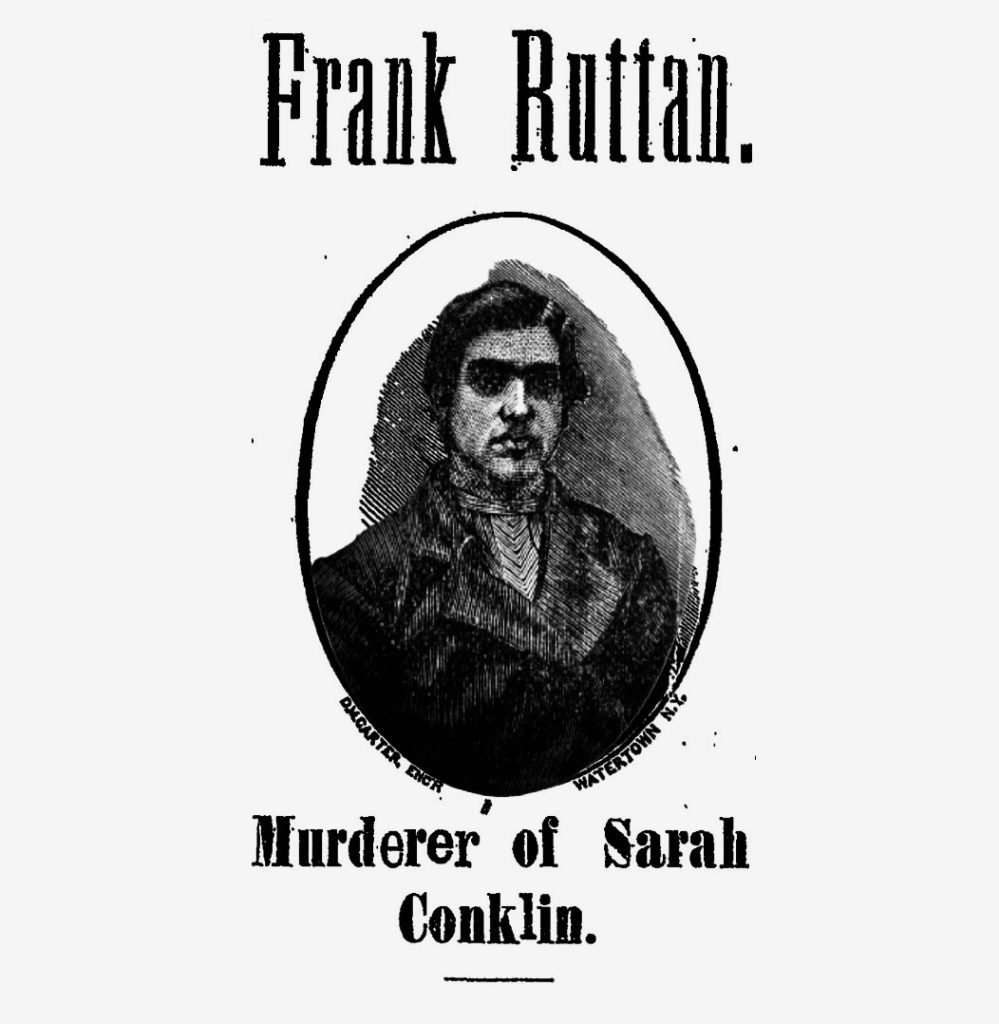

Sarah Conklin goes Missing Between Rutland and Burrs Mill, Later Found Murdered at the Hands of Adopted Frank Rattan.

The 1875 murder of Sarah Conklin in the town of Rutland, N.Y., was one of the more sensational crimes of its era that made newspapers around the country, including Washington, D.C., and Sacramento. Dubbed “The Rutland Horror” by the press, it was every parent’s nightmare: a young child failing to show up at home after school. Reported in the newspapers as being ten years old at the time, then later 13-14 years of age, Sarah Conklin‘s murder had allusions to the fairy tale Little Red Riding Hood due to the victim’s age and her wearing a cape with a red hood.

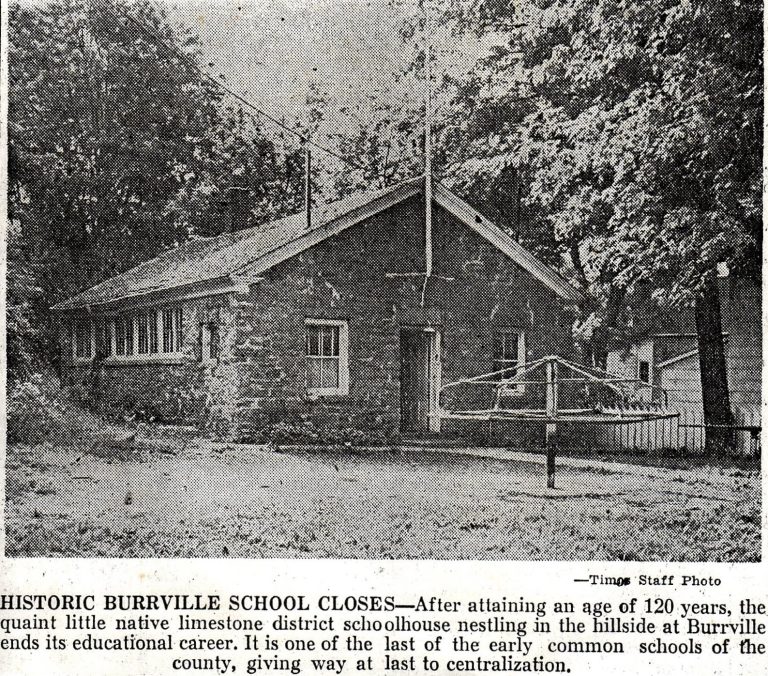

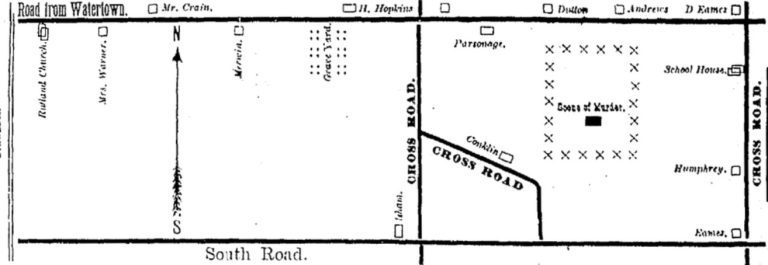

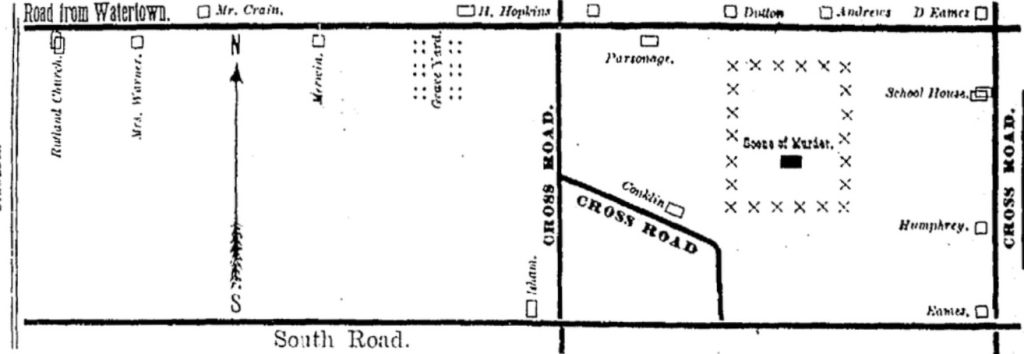

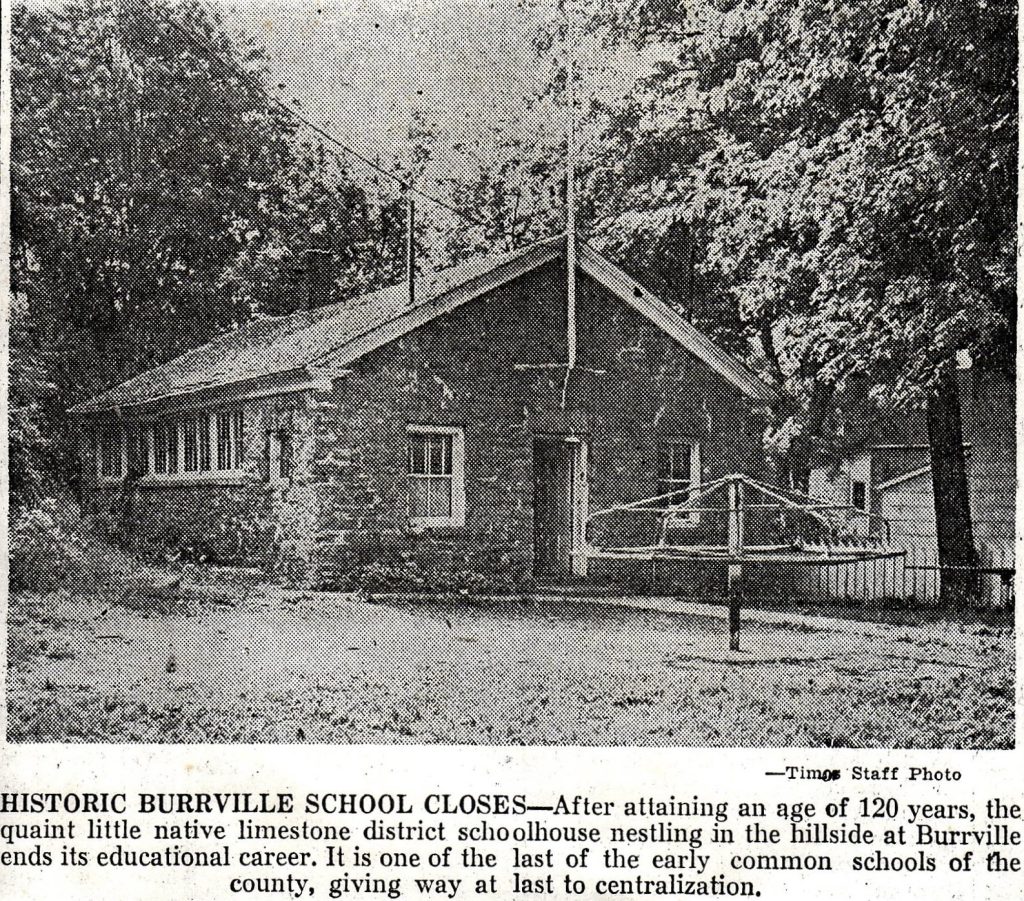

On the late afternoon of November 30th, Sarah Conklin, initially spelled “Conkling” in early reports, had milled about the schoolhouse located approximately 200 rods (about 1/4 to 1/2 mile) from her home for around fifteen minutes. Witnesses later stated they had seen her crossing through the field and woods. One said she was running at one point, sometime around 4:30 p.m. Born in Massena and later adopted, her father, Alvin Conklin, even testified he thought he had heard her scream but, having come from a distance, believed she was playing at school.

For the next hour, Alvin Conklin occasionally stopped what he was doing on his farm, later the well-known Owl Pine Farm, located on the crossroad, Eames Corner Road, which leads to Route 12, then known as the Watertown-Copenhagen Road, to see Sarah coming home from school expectantly. It was a bitterly cold day, and she most surely should be home by then.

Meanwhile, one of Alvin’s neighbors, Henry L. Humphrey, a farmer, and others were busy doing chores. Among them was 17-year-old Frank Ruttan, adopted by Humphrey, 40, after spending several years at the Jefferson County Orphan Asylum on Franklin Street in Watertown. Ruttan was an illegitimate child fathered by George Bromley, an Octoroon who once had a barbershop in the American Block, who died when Frank was only five.

Though his mother was still alive, he was sent to live with Bromley’s wife for a year until he was six. He was then sent to the orphanage until he was approximately fourteen when Humphrey adopted him. Ruttan, after residing with Humphrey for three years, had a history of charges involving inappropriate behaviors toward neighborhood girls. Humphrey also found himself the target of threats, such as having his farm buildings burned by Ruttan after an altercation. Alas, at this point, a girl was merely missing, and no foul play was suspected.

That would slowly begin to change around around 5 p.m. that day, as the Watertown Daily Times reported in its December 4th edition—

Shortly afterward, the call of Conklin at Humphrey’s house and apprisal of his daughter’s absence was made. The younger Humphrey with a lantern proceeded to the wood, and the search was made by him, Mr. Conklin and C. B. Gibson. Mr. Conklin first discovered the body prostrate, and called to his associates, who soon came to the spot. Some efforts were here made to restore warmth by friction, but the conviction that the girl was dead determined them to take the body home at once.

They rapidly as was possible conveyed her through the remaining woods and field to Mr. Conklin’s house, by which time it was about 5:40 in the evening. Efforts at resuscitation by use of friction, camphor and warm foot baths, were continued a long time, but without avail, though slight pulsations at the wrist were thought at times to be discernible by those engaged in these protracted attempts of affectionate humanity.

It was noted that when Sarah Conklin was found, her nose, chin, and bare hands were frozen, and her tongue protruded from her mouth. The white scarf around her neck was tight tightly, and her mittens were found nearby, along with blood, apparently spit from her mouth, in different places. Her skull appeared broken near the temple, and her face was severely bruised.

Surprisingly, the parties involved believed Sarah Conklin had died from an apparent mysterious accident. It was surmised she had tripped and struck her head against a tree or stick, then recovered to continue some distance before collapsing. This would remain the case through Thursday, December 2nd, despite Ruttan’s behavior, described as “if something was wrong with him.”

After the Conklin family made a statement, Coroner Phillips and Chief of Police Guest went to Rutland to investigate the murder under the pretense of an accident. Attending the location where Sarah Conklin was believed to have initially fallen, they thoroughly examined the area. They found no evidence of anything that would have produced such a wound that caused her death.

The Watertown Daily Times, in their December 3rd article, continued—

They then talked to Mr. Conkling (sic), asking him if there had been any person chopping in the woods or any man around there whom he would suspect of committing the deed. Mr. Conkling thereupon mentioned the name of this boy Frank Ruttan, saying the boy had been charged with improper conduct towards young girls in the neighborhood before.

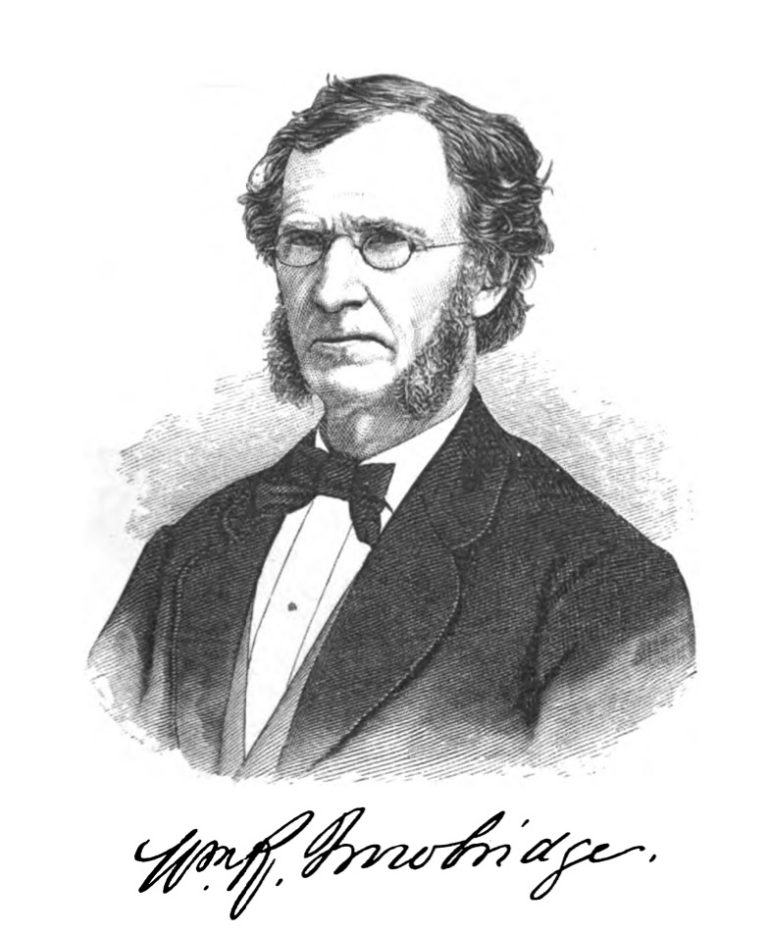

A postmortem examination ensued, led by Drs. William Ripley Trowbridge and Dr. Henry M. Stevens of Watertown had their results in the following day’s newspaper—

They found on the right side of the forehead a depression, apparently caused by the use of a small instrument, but on examination it did not prove to have fractured the skull; there was also a bad bruise near the outer edge of the upper right eyelid, that on examination showed a very extensive effusion of blood under the skin. The bone was crushed as though the blow came in downward direction, and must have been very severe.

On the left side of the neck, commencing at the spine, coming forward, is a dark ecchymose line about 1/4 inch wide, 2 3/4 inches long, evidently caused by constriction—by cord or scarf, which was found wound tightly tow or three times around the neck. Then running across the neck in front is another similar line, about 2 1/4 inches long; and also on the right side of the neck is a similar line extending backwards.

On the back of the right hand are about a dozen distinct lines 1/4 inch long, dented nearly through the skin, with an appearance such as would most likely be produced by finger nails. Other marks on the wrist of the same arm seem to have been similarly produced, by a person grasping the wrist and indenting the finger nails. there were five like marks on the left hand.

The face is considerably swollen, and the neck is discolored around, about an inch and a half in width, by blood settling under the skin, as though produced by strangulation.

An examination of the lungs showed an excessive engorgement by blood of nearly the whole lungs, indicating strangulation to be the cause of death. The tearing out of the button hole of her undergarment is the only evidence that an attempt was made to ravish.

In addition to Ruttan’s prior issues with girls and his behavior, questions arose as to his whereabouts at 4 p.m. on November 30th, when Sarah Conklin went missing. At the time, he was supposed to be doing chores but couldn’t be located, and the Watertown Daily Times detailed this fact extensively. The appearance of his footprints in the snow at the crime scene was also prominently discussed, in addition to their appearance to be retraced, with some footprint impressions denoting he had walked on his toes while others his heels.

The Times further reported in its December 4th edition of Police Chief Guest visiting the crime scene on Tuesday, opening his investigation “as one of deliberate murder.” It further noted of the tracks—

…led to the wood-pile in the woods, which were “open” in the colloquial sense, where the boy screened himself for a moment, and the bounding out a little distance beyond, sprang upon his probably unsuspecting victim. The ground where the first struggle took place while she was being struck and overpowered, showed by its worn surface and denudation of snow, resistance was made for a long time.

Leaving her dead, to appearance, but only senseless from the blows inflicted by a hammer, or club, she revived, and attempted to go toward her home. Her tracks showed she unwittingly bent round toward her destroyer, who must have been watching all this time.

Next he approaches and finishes his diabolical work by strangling her with her muffler, which, as was told the writer by a school-fellow, she before leaving the school house, tightly wrapped about her neck, and which could easily be twisted to the completest compression.

Frank Ruttan was arrested and retained at the Jefferson County Jail in Watertown. He was interviewed by Alvin Conklin, Sarah Conklin’s adoptive father, wholly denying he was at the scene of the crime or having anything to do with her death. He provided a written confession four days later, which wasn’t made public until May 5, 1876. He had also confessed to the crime to his adoptive father, Henry L. Humphrey, on the night of the murder—a fact that wasn’t immediately known before the trial because Humphrey passed away a little more than three months later, aged 40.

After the trial, Ruttan confessed to telling three people. Ruttan’s written confession was printed in The Times as follows—

DesemBer 9, 1875

She cold Mee a Fool and i thoUght i woold pay her For it And i saw her Coming From Schol and i run aeroUnd And she started to run And i throw a stick and hit her side head.

Frank Rutan.

The results from the jury in May found all to believe Sarah Conklin was murdered, and all agreed she had been killed by choking using the scarf. Eleven of the twelve jurors believed Frank Ruttan committed the murder, while one person believed some unknown person did it. Four jurors believed the crime was a first-degree murder, while eight believed it was second-degree. After two hours of further deliberation, they agreed on the second-degree charge.

Ruttan gave a verbal confession to Sheriff Herbert Babbitt, who transcribed it. The following was printed in the May 12, 1876 edition of the Watertown Daily Times—

About a week before John Allen went away he came to town and got a pint of whiskey, and left some there in the bottle when he went away. What was left in the bottle the day of the murder I drank. Bertie Van Slyck told me that she (Sarah Conklin) had been calling me names. He told me the next night after John Allen went away.

I stood in the alley way of the barn after throwing down the hay and looked out. I saw her near the bars by the school house. She was not in the lot. I went out of the alley door and under the bridge. I went right close to the orchard fence and came back the same way. She got into the woods before I did. I asked her what she had been saying such things about me for. She didn’t make any reply, but started to run.

I ran after her with a stick in my hand. I don’t know whether it was the stick shown at the coroner’s inquest or not, for I didn’t see that, but the one I had was a good, solid maple stick with a knot on it. I was about five or six feet from her when I threw it. I hit her on the right hand side of the head. She dropped where she stood, and lay.

She began to shake, and then got up and staggered along. Then I went to her again and tightened the scarf around her neck. She kicked, and tried to untie the scarf. I didn’t mean to kill her when I hit her with the club, but she looked so that I was afraid she would go home and tell of me, and they would do something to me, and so I went back and killed her.

I didn’t stay more than five minutes after I tightened the scarf. I fed the turkeys before I left the barn. I had on a coat over my frock. I didn’t get any blood on me. I was scared about what I had done that night after I got back to the barn.

Very little information could be found concerning Frank Ruttan after the fact. He was transported to the prison in Auburn and then to Elmira. The Times reported that he had difficulty adjusting to prison life and often vacillated between showing improvements with rehabilitation and displaying vindictive traits that landed him in trouble in the past. No date of death was located.

As for the victim, Sarah Conklin, The Watertown Daily Times remarked posthumously, December 4th—

She was attractive in person, developed beyond her years, pleasing in her manners, and bright in intellect. She was of fair, ruddy complexion, bright, hazel eyes, brown hair, and features regular enough to be called handsome. Better yet, she was a good girl and affectionate and dutiful daughter. The “ways of Providence are mysterious and past finding out” in this case surely, in permitting the fulfillment of such fiendish intent upon so lovely and innocent a subject for the victim.