‘Twas the Night Before Christmas At Constable Hall: Cherished Poem Celebrates 200th Year

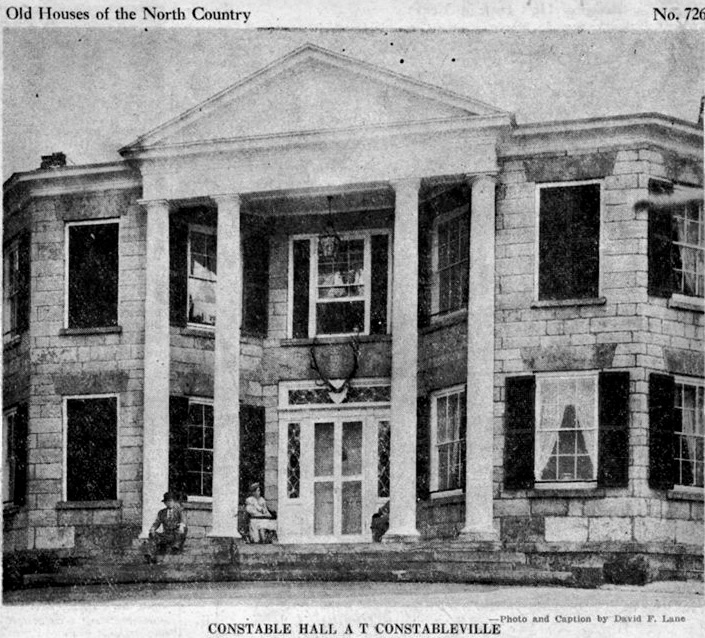

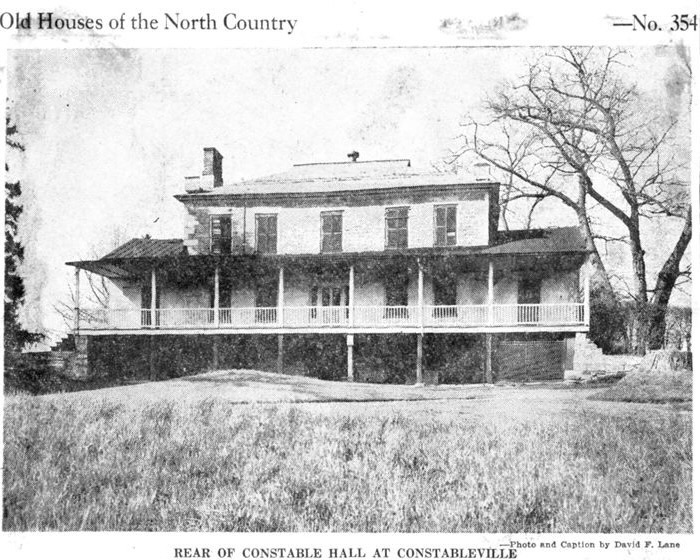

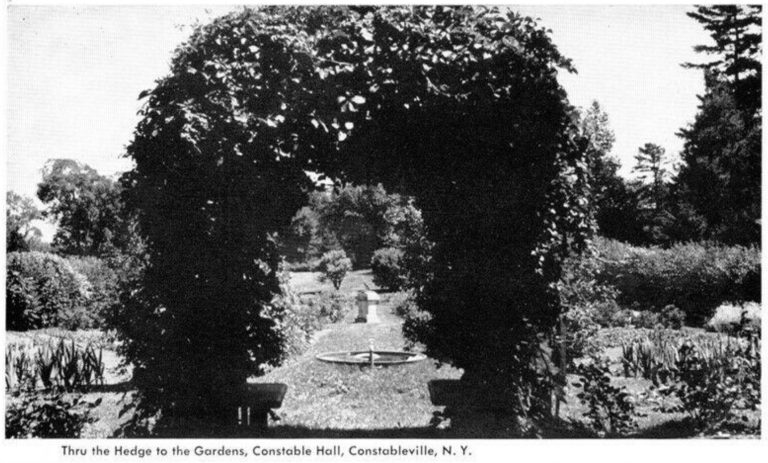

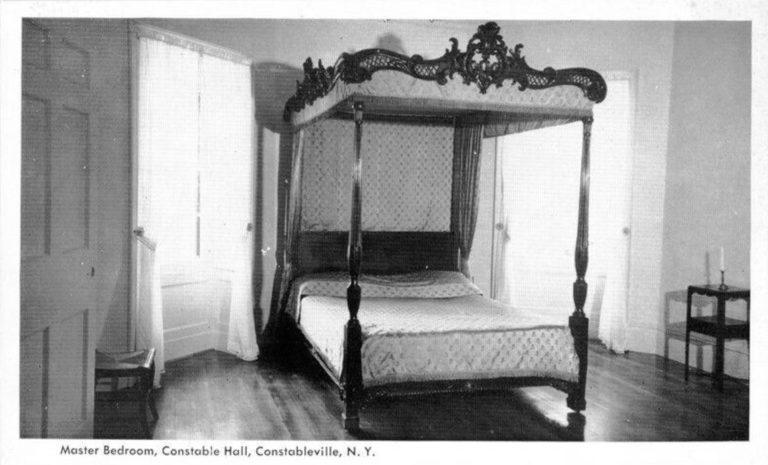

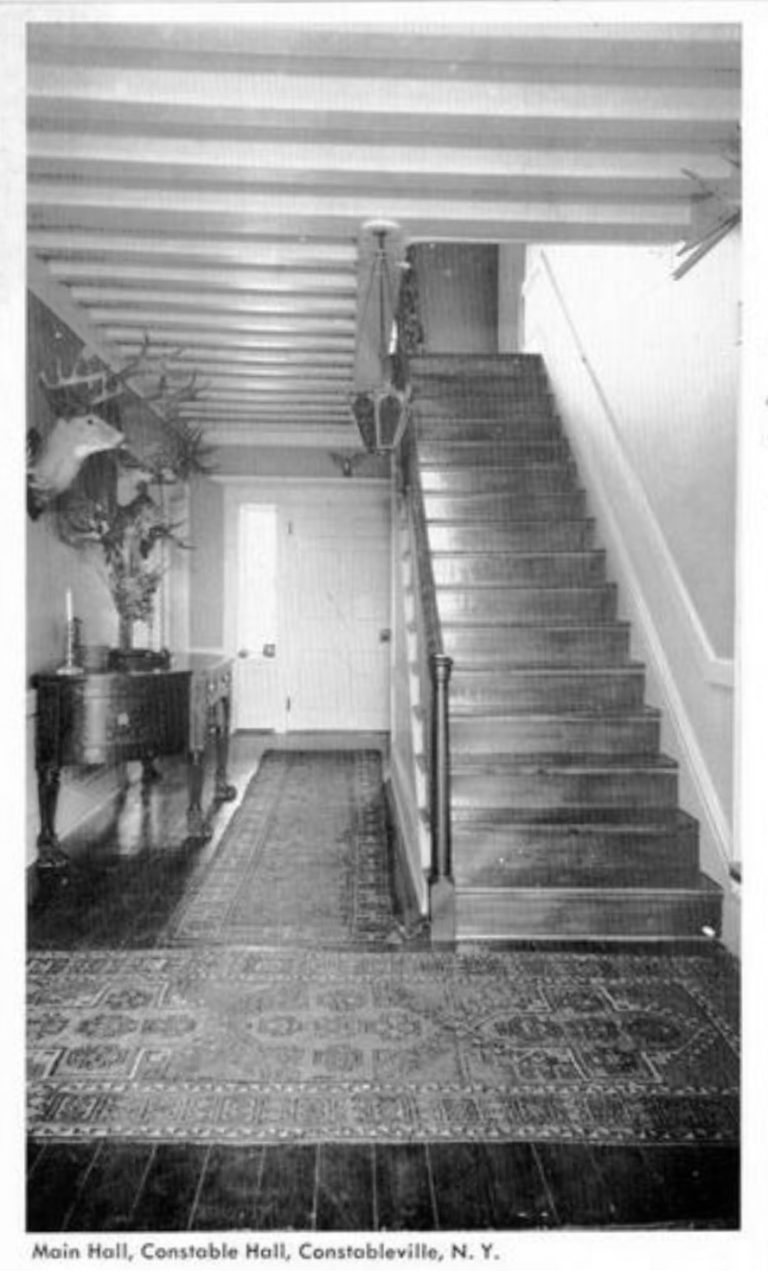

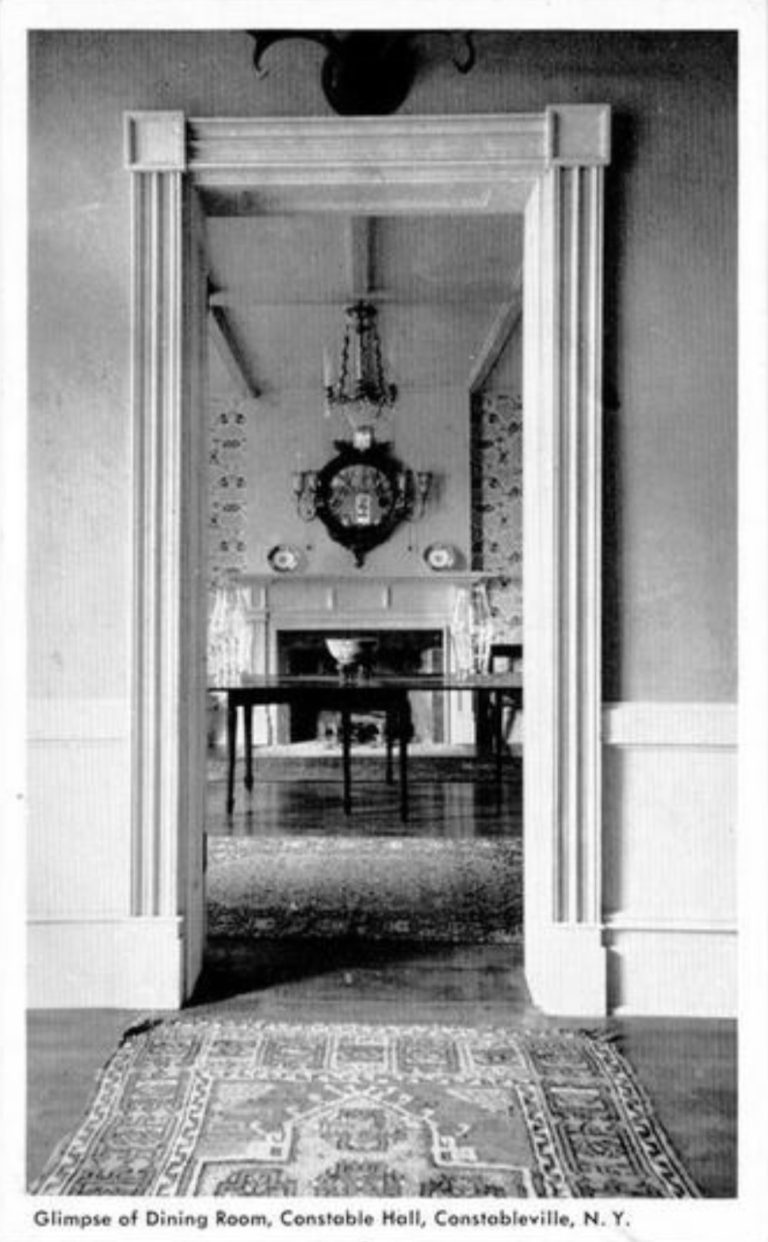

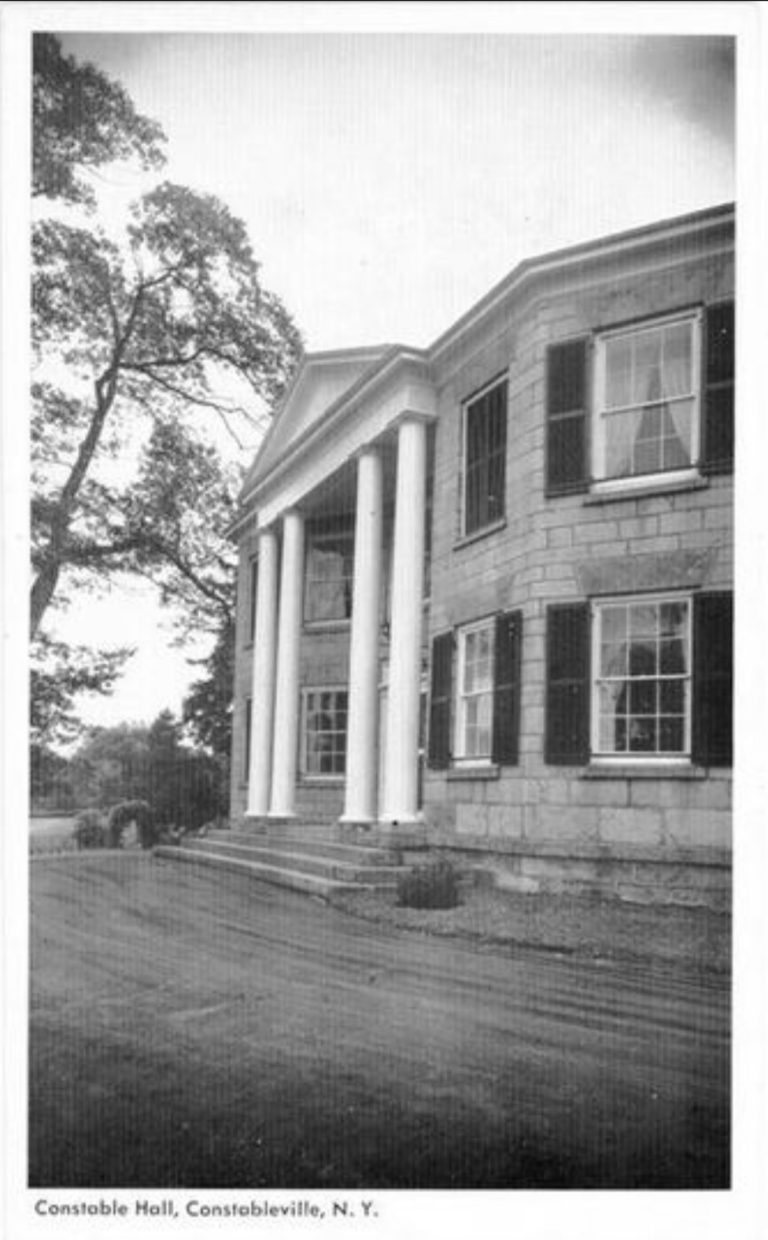

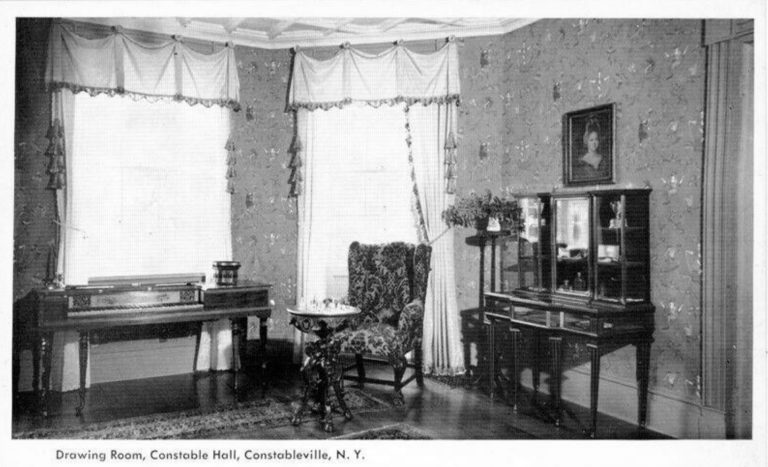

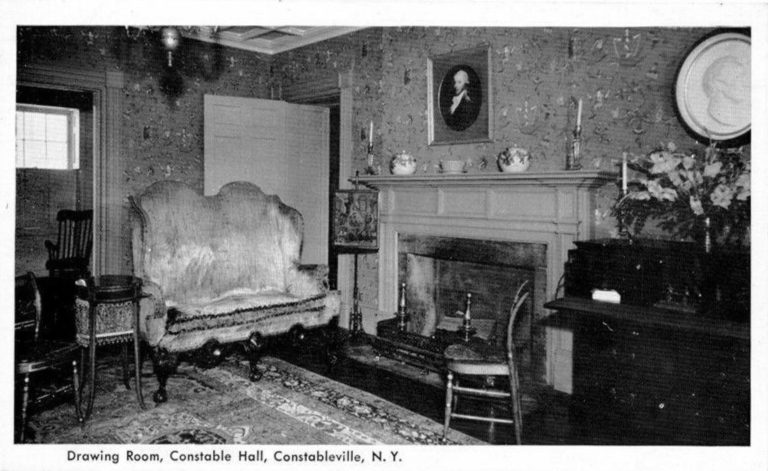

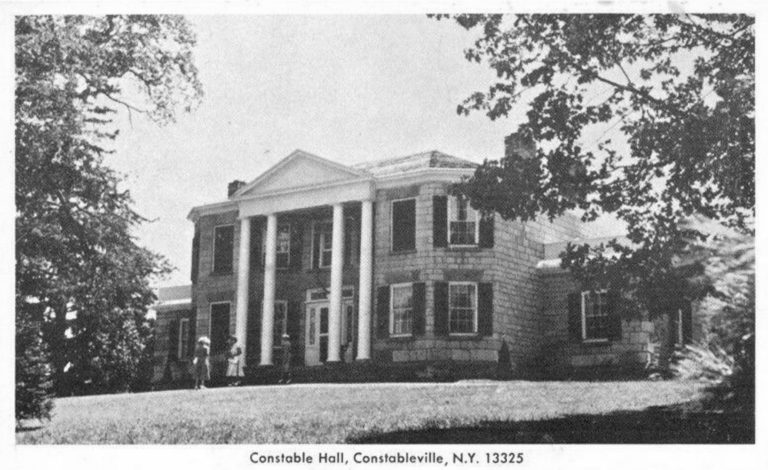

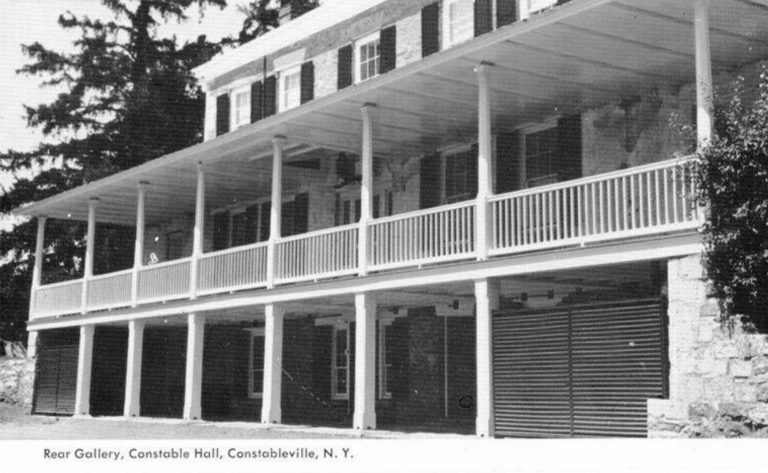

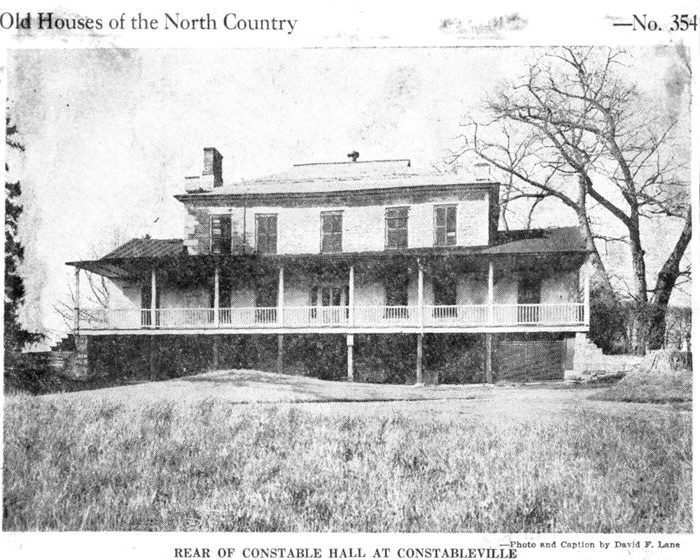

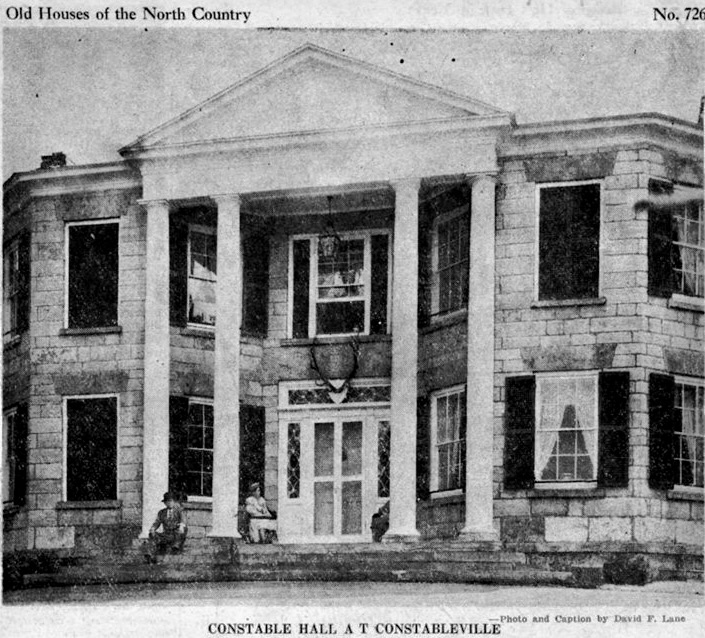

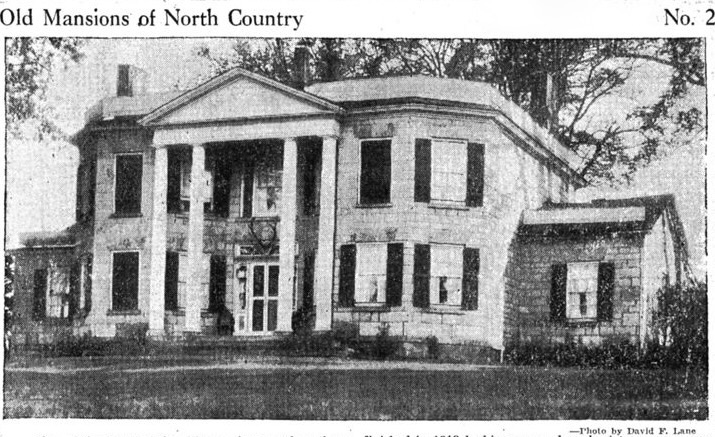

Completed in 1819, Constable Hall, just outside Constableville, N.Y., took nine years to complete and is one of the historic mansions of Northern New York. Made for William Constable, Jr., son of a great Northern New York landowner Wm. Constable, Sr., and constructed of native limestone hauled several miles overland by ox-team.

Wm. Constable Sr. was much like James Donatien Le Ray of LeRay Mansion on Fort Drum, whose father, Jacques-Donatien Le Ray de Chaumont, was “Father of the American Revolution” and gained a large portion of Northern New York for his efforts. The elder Wm. Constable’s father, John Constable, a British army surgeon who served in the French and Indian wars, later became the major stakeholder of the ‘Macomb Purchase,’ making him the largest landowner in New York State with 3.6 million acres.

William Constable, Jr., was injured during the construction and later died from complications at age 35, having lived in the mansion only two years upon its completion. He left behind his wife, Mary Eliza McVickar Constable, and five children. It is here, with Mary, that the connection to Clement Clarke Moore, author of “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (some sources have it as “Account of a Visit from St. Nicholas”), better known today as “Twas the Night Before Christmas,” as they were cousins.

Clement Clarke Moore was born in New York City on July 15, 1779, at his mother’s family estate in Chelsea. Moore’s paternal grandfather, Major Thomas Clarke, was an English officer who also participated in the French and Indian War and later owned the estate of Chelsea.

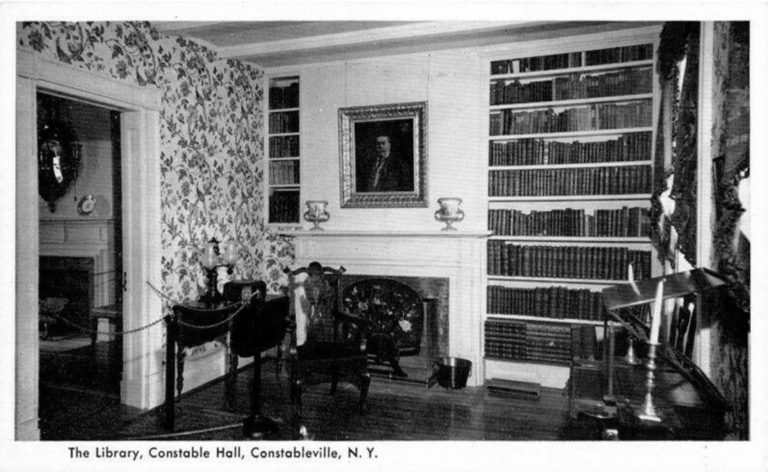

Moore eventually went to Columbia College, earning his B.A. and M.A., and later awarded his L.L.D. (Legum Doctor/Doctor of Law) in 1819, but spent much of his career as a Professor of Oriental and Greek Literature, as well as Divinity and Biblical Learning. What he’s most remembered for, however, is being credited, though not without controversy, with penning “Twas the Night Before Christmas.” Some believe Major Henry Livingston, Jr, of Poughkeepsie and a distant relative of Moore’s wife, wrote the poem.

In 1929, the Watertown Daily Times first discussed where the popular poem was written—

The house in which Dr. Clement More (sic) wrote “Twas the Night Before Christmas” still stands, a vagrant beggar perhaps but defiantly challenging the invasion of the wrecking crew that is sweeping through the entire district of Chelsea in New York preparing for the construction of a great apartment house to cover the entire block. Mrs. Tillie Hart refuses to move. She insists she has a lease and will not relinquish her rights.

Of course, the reason that Mrs. Hart’s place attracts special attention is that here a century ago Dr. Clement Moore wrote “’ Twas the Night Before Christmas.”

A little over two months later, The Times republished an article from the New York Sun discussing the poem’s origins. The article begins by stating that 107 years prior, on Christmas Eve, Dr. Clement C. Moore went after a Christmas turkey and returned with a poem that made him famous. It also noted that Dr. Moore had, at the time, lived “at Broadway and Laurel Hill Boulevard in Elmhurst, Queens,” but the article later states—

It was at that house, Mr. Harvey and a number of historians of Queens borough claim, that Dr. Moore was living in 1822 when he wrote “A Visit From St. Nicholas.” Considerably more circumstantial evidence points to Dr. Moore’s residence in Chelsea at the time, however.

Complicating matters, there are several different versions of how Dr. Moore came to write the poem. The turkey story had been cited the most at that time and believed true by most. The article went on to report—

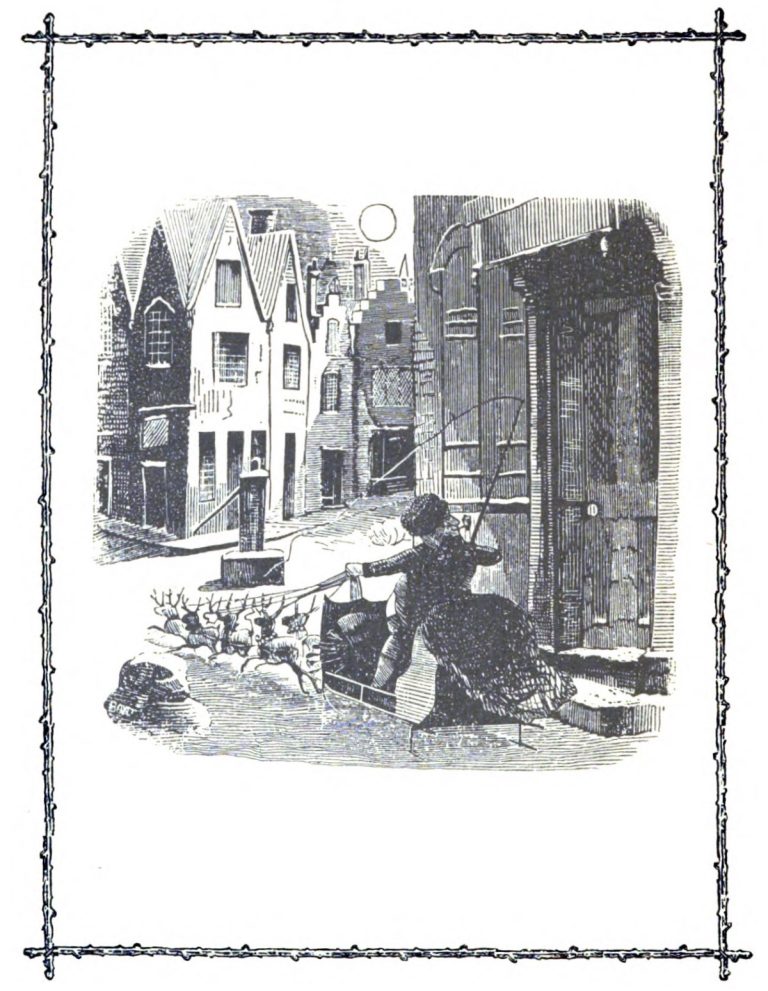

According to the most familiar version of the story, The Moores were living “out in the country” in 1822—what is now (1929) West Twenty-Third Street was quiet countryside outside of Greenwich Village—and when Christmas Eve came and Mrs. Moore started out to distribute baskets of food among her poorer neighbors, she discovered that she lacked one turkey. Nothing would do but that Dr. Moore should go into the village and buy another turkey.

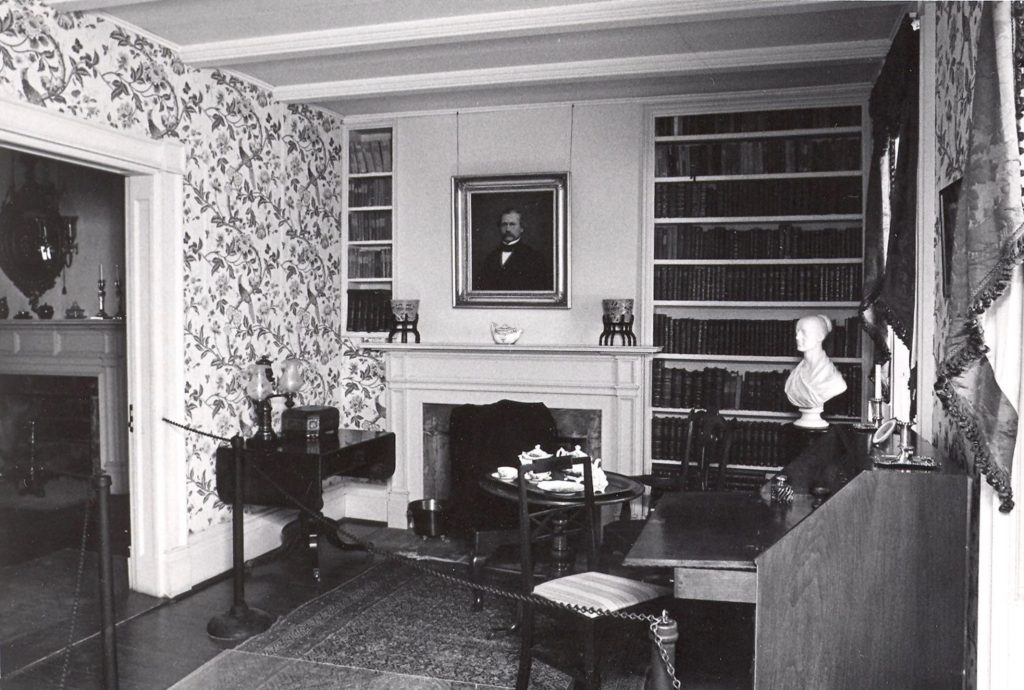

He hurried his footsteps, delivered the turkey to his wife, and shut himself up in his study before the blazing log fire. An hour passed—the children were calling for their father to come out and tell them about St. Nicholas—and Dr. Moore emerged with a scrawled copy of what he called “A Visit From St. Nicholas.”

Further complicating the history, Clement Clarke Moore had reportedly forgotten about the poem, a bemusement he had written for his children until the poem was printed “anonymously” in the Troy Sentinel the following year. Dr. Moore was upset once he found out that it had been publicly published and was concerned with what people would think of him should they find out he was its author.

For years, Dr. Moore refused to acknowledge his authorship of the poem, but it didn’t stop it from being republished in almost every newspaper in existence and translated into most languages. Over time, and before his death, Dr. Moore’s opinion of the matter changed, and he accepted the authorship of the poem that had become known as “Twas the Night Before Christmas” in 1837. However, the question remains: what were the poem’s origins, as in inspiration?

For years the story generally remained the same, with minor variations. Then, in December of 1982, the Watertown Daily Times published the article “Constable Hall May Have Inspired Two Lines In Famous Yule Poem.” The article, written by Vernon Hill, went on to state—

Portions of the immortal yuletide poem “Twas the Night Before Christmas,” may have been inspired by the author’s visit to Constable Hall, according to local folklore.

The poem, originally titled “A Visit From St. Nicholas,”was the 1822 work of Clement Clarke Moore, LL.D. (Doctor of Laws.)

Mr. Moore, a resident of Chelsea, near New York City, was a cousin of Mary Eliza McVickar, wife of William C. Constable, Jr., first owner of Constable Hall. Although Mr. Constable died in 1821, his wife lived in the hall for parts of the next 40 years.

While history recognizes that Mr. Moore wrote the poem at his own home, it also has recorded that he made trips to Lewis County. It is not unreasonable to assume that he called on his recently-widowed cousin in 1821 or early 1822, or that he was on hand during construction of the hall from 1810 to 1819.

“He did visit Constable Hall, perhaps two or three times,” said Director Arlene Hall, Lowville. “It is said, from what the family has passed on for several generations, that he truly enjoyed Constable Hall and thought it was a beautiful home.”

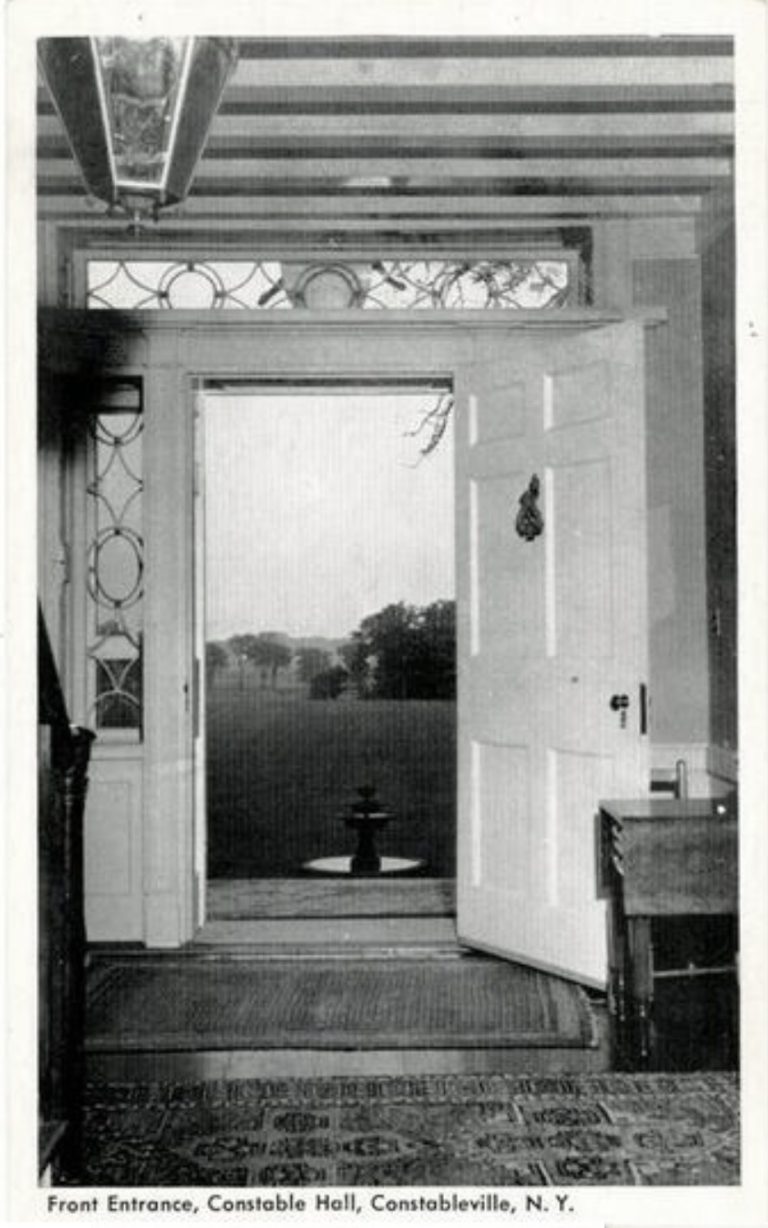

Two lines in particular from the poem appear to be specific references to Constable Hall:

Away to the window I flew like a flash.

Tore open the shutters and threw up the sash.

Dave Dudajek, the opinions page editor of the Utica Observer-Dispatch, wrote in a column dated December 24, 2019—

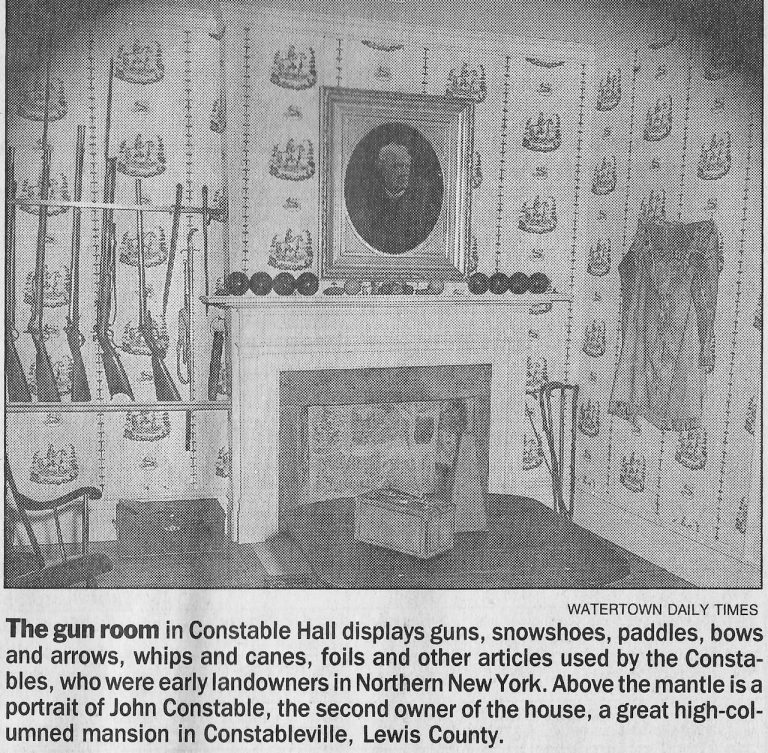

Connections were made and handed down through the years. For instance, Constable Hall’s caretaker in 1822, a Dutchman named Pieter, might have figured into Moore’s description of Saint Nicholas as a “right jolly old elf.” (Santa Claus as we know him was yet to evolve.) On Dec. 23, 1984, Donald Hall, editor of the Oxford Book of Children’s Verse, wrote in the New York Times Book Review that Moore later acknowledged his poem was based on a Dutch folk tale he heard as a child. St. Nick was modeled after a portly Dutchman he once knew. (Pieter?)

A similar claim had also been made about Moore’s caretaker in their Chelsea home. While the earlier article mentioned, it was “not unreasonable to assume” that Moore called upon his cousin shortly after the death of her husband in 1821.

In 1998, The Times published another article regarding the Constable Hall Association selling bricks to be inscribed with the buyer’s name to raise funds for roof repairs. At the end of the article was an interesting piece of information provided by Kathleen L. Zehr, then-president of the Constable Hall Association board of trustees. The article stated, in part—

Miss Zehr said there’s no conclusive proof that he (Moore) wrote the poem there, but he gave the children at the house a very early copy.

That same year, the origin story, or at least the inspiration from Constable Hall, was being published elsewhere. The Cox News Service published an article from writer Cara Anna, who also wrote for the Palm Beach Post, West Palm Beach, Fla., that noted in part–

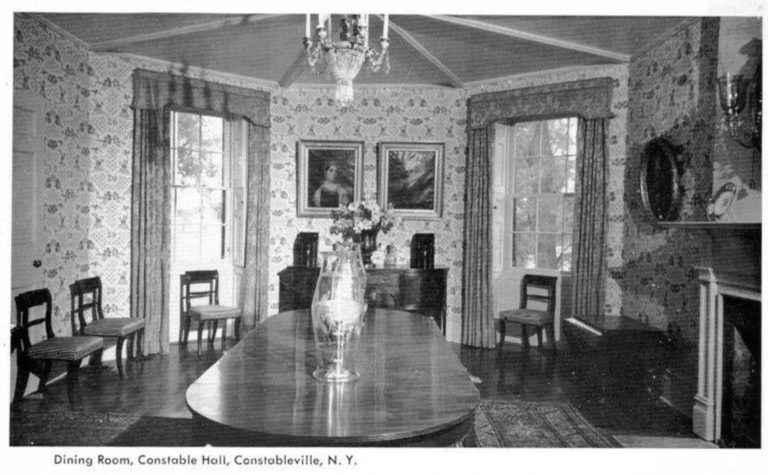

Moore apparently was inspired to write the poem on a trip to upstate New York in 1822. He was visiting a cousin, Mary McVicker, whose husband had died. McVicker and her four children lived in a house called Constable Hall. Every room had a large chimney.

And tending the garden was a Dutchman named Pieter. As the story goes, he was rather plump. And downright jolly. Pieter was Moore’s inspiration for Santa Clause, says John Constable, 82, the last of the family to live in Constable Hall. So the modern description of Santa was born.

Moore sent the family a hand-written copy of the poem, but Constable doesn’t know what happened to it. (The original sold at a Christie’s auction for $255,000.) But a chess set the writer sent is still at the house.

Every Christmas Eve, Constable says, the family would read Moore’s poem.

But not anymore. Constable Hall—now a museum on the state and national registers—is closed for the winter.

Back in 1947, Constable Hall was sold to Mr. and Mrs. (Frances Pitcher Lewis) Harry Lewis and to Harry’s sister, Mrs. Grace Edna Lewis Cornwall. Grace had married Harold D. Cornwall, son of former Alexandria Bay mayor Harvey Ansel Cornwall. Harold passed away in 1933, but three years prior, Grace and he acquired Cuba Island in the Thousand Islands. Grace also restored Constable Hall and gave it to the Constable Hall Association, and it was opened to the public in 1949.

Most recently, author Pamela McColl published “Twas the Night: The Art and History of the Classic Christmas Poem,” which was a #1 Best Seller on Amazon.com in the Antiques and Collectible Books category. The book was ten years in the making and features numerous pieces of artwork inspired by the poem. It chronicles the history of Christmas in North America, dating back to the pilgrims. Pamela posted a few comments down further below with more information.

Below: From Christine the History Queen’s YouTube Channel, a short video, “Twas the Night at Constable Hall,” featuring interviews with the Constable Hall Association President and Executive Director. Clicking on the photo will open a browser to the video on YouTube.

Did You Know?

Though commonly known as “Donner and Blitzen,” the reindeer’s names were originally written as Dunder and Blixem.

5 Reviews on “'Twas the Night Before Christmas At Constable Hall (1819 – Present)”

What is interesting is that Henry Livingston seemingly never contested the authoring of the poem. As a writer, myself, I sense a certain tacit responsibility to accept, both good and bad, the public impacts of what I write. If Livingston wrote the poem and it worked its way over to Moore through familial channels, it would seem unlikely that one would steal the authorship while the actual writer would cede rights uncontested.

As with many masterpieces that emerge over time, tales and myths arise with them

I agree. That Livingston died in 1828 and Moore didn’t publicly accept authorship for almost another decade could be taken as a “wait-and-see” approach, though I would like to think he would be far too noble of a person to pass the work off as his own. In all likelihood, Livingston would have seen the publications in the years before his death which also raises the question of why he (apparently) didn’t say anything since all the reprinting was anonymous.

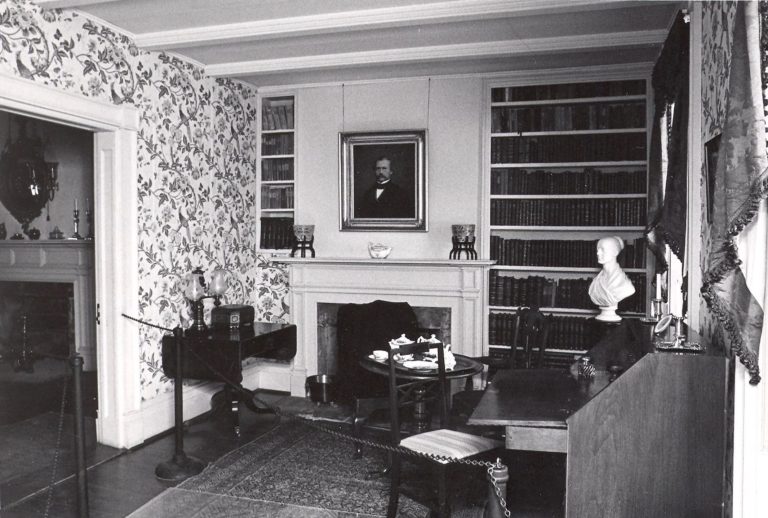

I checked the photo of Clement Clarke Moore and it is not he – but an unidentified fellow – ca 1860s.

Moore dies in 1863 in his eighties – so it is not he in this photo from my deduction.

Great article and off to find the sources and read the articles mentioned. Thankyou

Pamela McColl

http://www.twasthenightbook.com

Very interesting. The photo referencing it as being Clement Clarke Moore is on the National Portrait Gallery website, which you may have already seen, here: https://npg.si.edu/blog/twas-night-christmas-clement-clarke-moore. I agree he doesn’t look anywhere near the correct age if the photo were taken at that time.

I would love to obtain the evidence that Moore visited Constable Hall and anything at all about his visit or visits … “He did visit 2-3 times” -is this family lore or factual – would love to find a letter or anything at all – so hoping to find more clues to the story. I find the Constables to be a very interesting family – especially William Sr. – it is written that he was an amazing man to meet.

The photograph of Clement Clarke Moore is possibly of his son not the poet.

Clement Moore

BIRTH

3 Jan 1821

New York County (Manhattan), New York, USA

DEATH

13 May 1889 (aged 68)

Very interesting podcast on Mrs. Tilly Hart

https://www.boweryboyshistory.com/2020/03/the-tale-of-tillie-hart-the-holdout-of-london-terrace.html

Thank you! I’ll have to check this out!