The Watertown Urban Renewal Winds of Change Began Blowing in 1958 With President Eisenhower’s Aggressive Program

Though urban renewal didn’t begin until 1949, it essentially had its roots in the Housing Acts of 1934 and 1937, which created the U.S. Housing Authority. The Watertown Urban Renewal program didn’t start in motion until 1958 when President Dwight D. Eisenhower declared $1,000,000,000 of federal funds to be used for “slum clearance projects and other aspects of urban renewal.” Urban renewal began in 1949, allowing public and private property seizing through eminent domain, with government funding coming from a Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) grant and loan program.

Legislation often paired the project with other initiatives and the Economic Committee’s call for federal expenditures that included, among other things, water resources (e.g. navigation and flood control); water and soil conservation, and reclamation, while also urging expanded highway grants, an increase in urban renewal programs, public building construction and revised housing programs.

In New York state, Robert Moses, the chairman of New York City’s committee on slum clearance, told approximately 300 mayors, city managers and housing agency directors, most of which had their own urban renewal programs in development or planning stages, “you can’t fight a depression with cream puffs.”

Locally, Watertown City Manager Ronald G. Forbes informed the city council in April of 1958 that Walter S. Fried, New York City, regional director of the federal urban renewal program, would be visiting the city soon to discuss the “potentialities” of urban renewal development. The day after his visit, the headlines in the Watertown Daily Times read, “City Could Get Federal Aid For Urban Renewal,” touting up to 75% of associated costs paid by the government for a Watertown Urban Renewal project.

The article went on to read–

Mr. Fried spoke for a brief time before the meeting was opened to questions from teh floor. No city remains at a given level of utility, he said. Cities of this seven-state region, comprising New York and the New England states, have been going backward in appearance and adaptability to the automobile age.

These cities were developed, he continued, for a different day and age. Although the moral values of this past age deserve to be preserved, the structures need to be radically altered to provide for safety, comfort and convenience of mid-20th century living.

With that being said, the what and where of each location was left up to the city to govern itself best, deciding its own project area and ultimate use for it. Nevertheless, a controversy was had from the get-go. Stanley J. Harte of Massena’s Harte Haven shopping center questioned whether Watertown was ready for such a program, stating that in a meeting at City Hall earlier in the week, he had spoken to bankers, merchants and others who expressed opposition and believed “modernization is not necessary in this city.”

By August of 1958, congress had failed to pass the urban renewal and housing bill, setting back several projects the Watertown Housing Authority had projected. Mayor William G. Lachenaur asked for the support of President Eisenhower, Congressman Clarence E. Kilburn of Malone, and others, to back the important legislation stating that the Watertown Urban Renewal planning was essential for the housing authority to be able to use federal funds to construct the proposed housing project for the elderly at Mill and East Main Streets.

Meanwhile, the Watertown city council unanimously approved a $1 contract with Sargent, Webster, Crenshaw and Folley’s architectural firm to design a formal Watertown urban renewal plan. The firm, which later designed the current Watertown High and Harold T. Wiley schools, eventually were paid $17,000 for the plans.

While the Watertown Urban Renewal effort was ultimately set back when the House fell six votes short of passing a housing and urban renewal bill in 1958 that would have added millions more for new projects, it did not keep the planning from moving forward. In late September, Housing and Home Finance Administrator Albert M. Cole approved Watertown’s “workable program” to eliminate slums and blight.

Cole informed Rep. Kilburn of Malone that he expected plans to be completed within the following year to identify locations, types and causes of the blight, with recommendations “for necessary corrective actions.”

One of the issues existing buildings faced was codes for building, plumbing, electricity, sanitation, and fire prevention. Although Cole acknowledged Watertown already had codes in place for managing these, he noted local officials were considering revising the present housing codes to align with the state’s minimum health standards.

This is important to note: the buildings, while perhaps not out of code at the time, weren’t up to the state’s minimum requirements, which may have doomed any number of the buildings as their owners could have been faced with untold costs in bringing their properties up to these new codes.

The improvement plans would have several committees to evaluate specific categories. A new look committee, a parking committee, and the mayor’s advisory committee were all tasked with reviewing the federal housing plans to determine possible areas of participation in slum clearance and redevelopment.

In late October 1958, the Sargent, Webster, Crenshaw, and Folley firm was officially hired to prepare a comprehensive community plan for the Watertown urban renewal program. The Mayor’s advisory committee recommended the finalization of the contract, noting that it was required to obtain federal dollars for the program.

In April of the following year, New York Gov. Nelson A. Rockefeller signed a constitutional amendment designed to encourage Watertown, and other New York State cities, to enter into an urban renewal program by cutting projected costs in half. State loans would be provided for one-sixth of the cost, matching the localities’ costs, while federal dollars would pay for the remaining two-thirds.

Watertown Committee Also Tasked With Bypass “Half-Way Loop”

Part of the mayor’s planning committee’s agenda was to factor in a bypass “half-way loop,” diverting traffic from Public Square. It would be designed to use existing streets or pass between blocks through state arterial construction, which former mayor Henry Hudson previously proposed. The Times wrote of the proposal–

The proposed highway of the future would go east from Washington Street at about Haley Street and follow the streets – Haley, Brainard, Arlington, and Central, to a bridge over the Black River; over Starbuck Avenue, East and West Hoard Streets, and proceed south just east of the New York Central freight house area to West Main Street.

Going west off Washington Street, it would follow a general line of Woodruff Street, over to South and North Meadow, and over a second bridge of the Black River to West Main Street.

In August of 1959, after President Eisenhower vetoed a housing bill, he won a decisive victory when the senate voted 55 to 40 to sustain his veto. It was written in The Times–

Senate liberals were angry. They foresaw that they would get nothing for slum clearance, urban renewal, housing for the aged and similar projects close to their hearts and their constituents. The president’s program seemed to them to do little besides give some additional ‘sugar’ to builders of middle-and-high income housing. They complained about him and they included (Lyndon B.) Johnson in their personal criticism.

Locally, Mayor Lachenauer touted Watertown as having had $5M in new construction for 1959 and was looking forward to 1960–

We must encourage the revitalization of the downtown area lest our commercial area become depressed and we lose our advantage as a major retail center to the perimeter shopping districts.

In late October, city officials were warned they needed a full-fledged planning commission for the Watertown urban renewal program to reap the federal program’s benefits, not just the mayor’s “unofficial” advisory board. That board was down to one original member, the others having resigned due to a “conflict of interests.” It was divulged in a city hall session that, under federal-state regulation, an official planning commission was considered an integral part of the requirements for government financial grants.

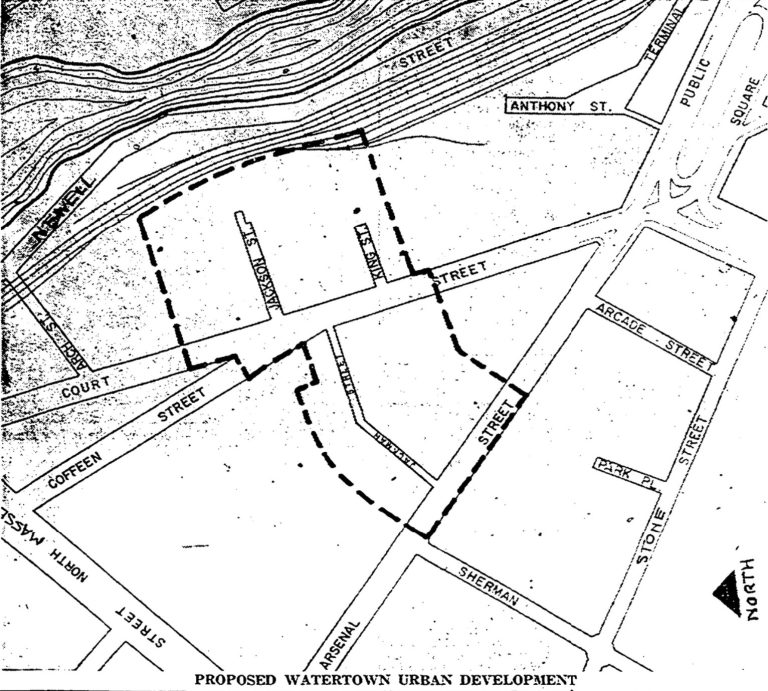

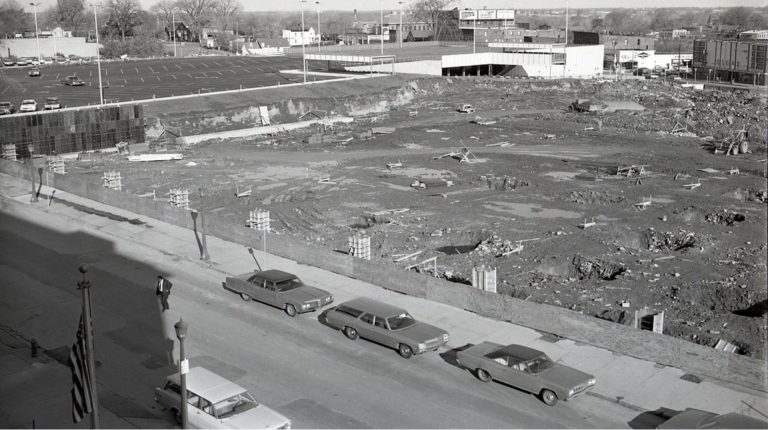

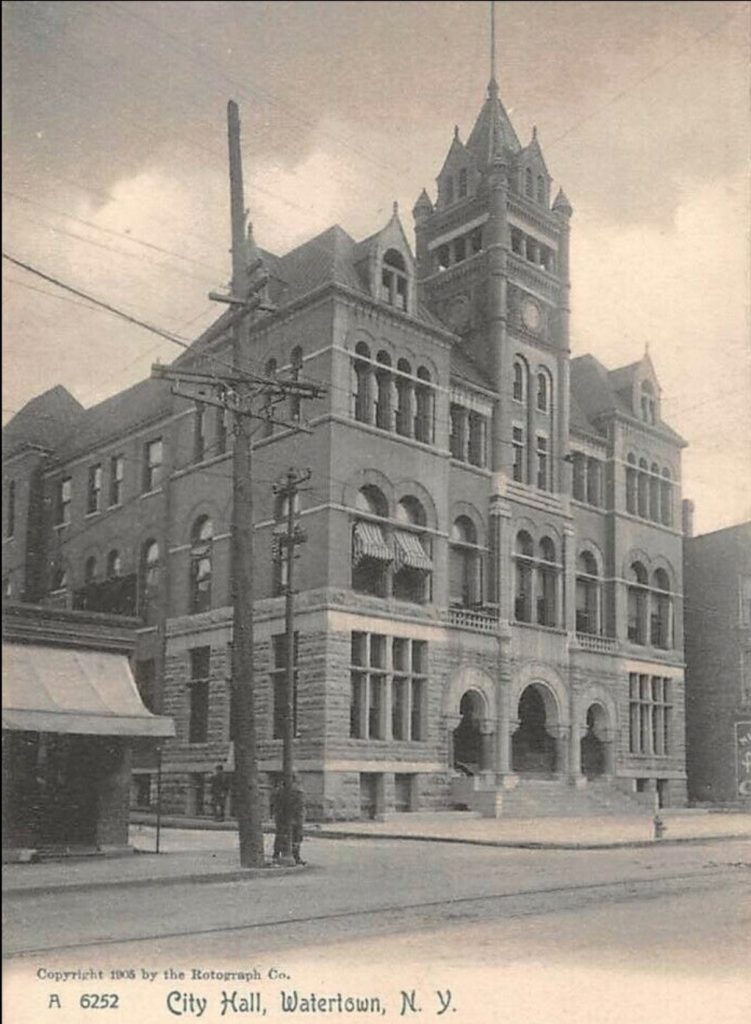

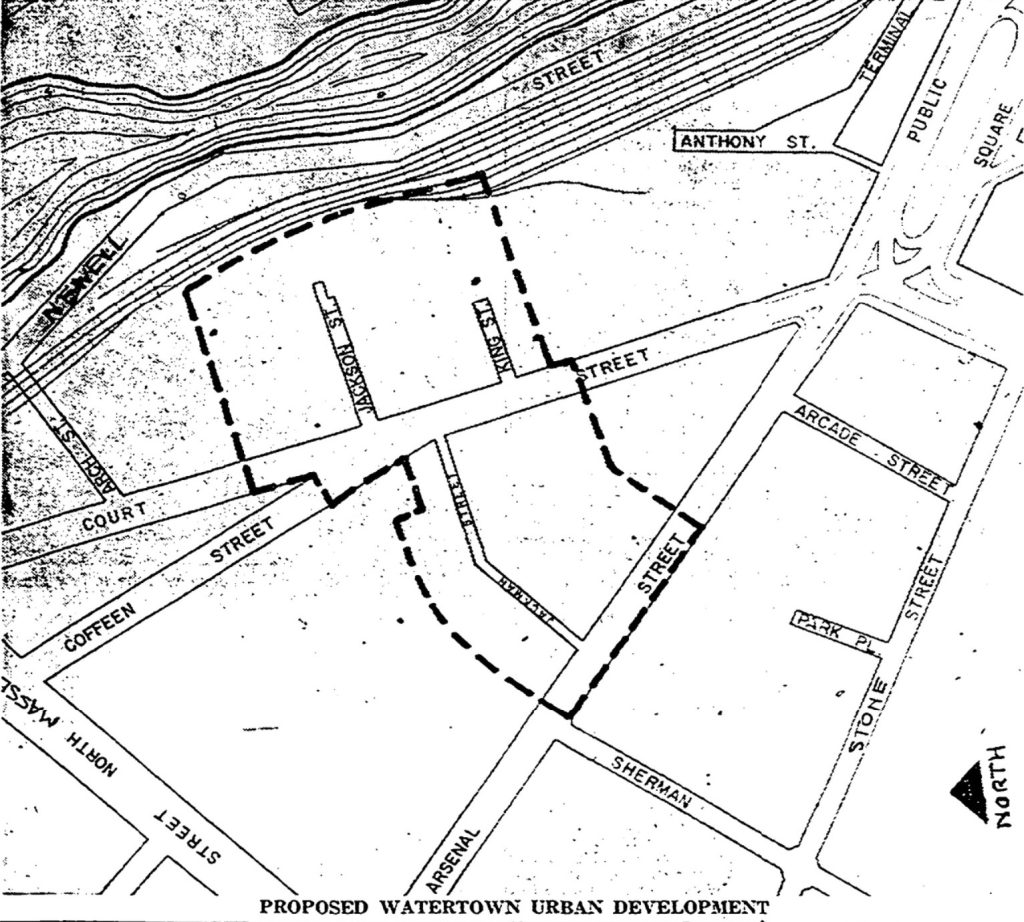

The initial plan was revealed in early December 1959, estimating a $4,000,000 Watertown Urban Renewal Plan proposed for the business section to include public parking, eliminating all existing buildings in the designated area except for Globe Store and the State Armory.

The Times reported on December 9th, 1959–

The Watertown public will get its first glimpse of a proposed municipal urban renewal plan at a city hall meeting starting at 4 p.m., Thursday. The plan, if implemented by the city council, would cost between $3,000,000 and $4,000,000, according to Alvie M. Edwards chairman of the planning committee.

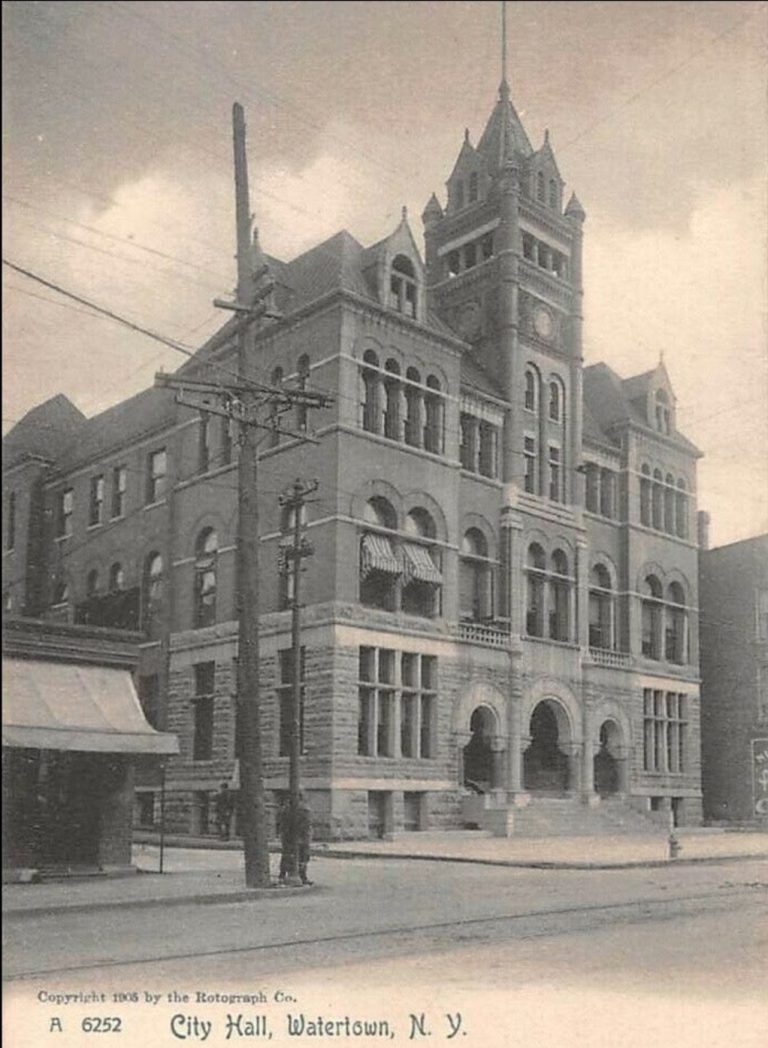

Cost of the program, which would wipe out the city hall, Roosevelt Hotel, Montgomery Ward store and various other properties in the urban renewal area, would be shared by the federal, state and city governments, Chairman Edwards said. The federal government would pay two-thirds of the cost with the state and city paying one-sixth each.

The program would include the establishment of a vast central city parking area in the Arsenal-Court Street section of the city with only two present establishments left standing—the state armory and the Globe store.

Chairman Edwards said that all dislocated people and business in the area would be relocated under the urban renewal program with suitable payments for condemned properties and relocation costs involved.

All properties at the rear of the condemned street properties in the plan would be razed and the big portion of the section developed for parking.

All present properties—business and residential—between the south side of the city hall and a point north of the Globe store on the east side of Court Street would be razed in the new program. The Globe would remain because it is comparatively modern and well-conditioned business structure, Chairman Edwards said.

The properties on the west side of Court Street, starting with the Roosevelt Hotel and including the Adams Block, corner of Court and Jackman Streets, would also fall in the path of urban renewal progress, he said.

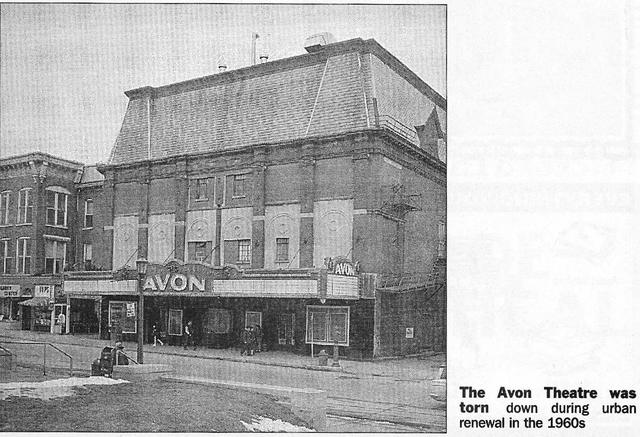

It was initially proposed to keep the Armory, but it was left open for the state to decide whether the facility was still adequate or whether it would be necessary to build a new training center. Properties from the Armory to the alley, just east of the Avon Theater, along with the business buildings in the rear, were all planned for demolition.

Meanwhile, a Mill-Gotham through street was called for in the city’s master plan, stating it would eliminate much of the Public Square, Mill Street, and State Street congestion. The Times reported on December 10, 1959—

The major roadway projected south from Public Square, approved by the committee and suggested to the city council for enactment, would eliminate the former plan to build a new cutoff through Union, between Factory and Sterling Streets. The older plan, experts think, would be less practical and more expensive.

The new traffic cutoff for the east end of Public Square, as proposed, would take out such properties as the Mohican Store, now abandoned for business purposes above the ground floor. It would run through the Franklin Street parking lot on the north side of the street and proceed through the new parking area developed by the Agricultural Insurance Company, just east of the Solar Block at the corner of Franklin and Goodale Streets.

The street would then enter Gotham Street at the junction with Sterling Street. Experts who recommended the new traffic route felt it would help alleviate traffic congestion on Public Square.

Interestingly, one of the proposed changes that weren’t implemented at the time eventually happened in recent years. The plan called for the potential installation of a traffic light on the west of the end of State Street at the Baptist Church corner. This currently allows traffic to turn off Mill entering Public Square onto State Street, eliminating traffic from having to travel around the square.

A Little Levity

The following was printed in the Watertown Daily Times, no July 24, 1959–

“Urban renewal starts with the neighborhood, and neighborhood improvement begins with the individual home, and the condition of the individual home depends on what you’re planning to do with that cigarette ash, you idiot,” Mrs. Tippy remarked to her husband during a discussion of community problems the other evening.