The Palatial Orville Brainard Mansion Became Elks Club In 1913

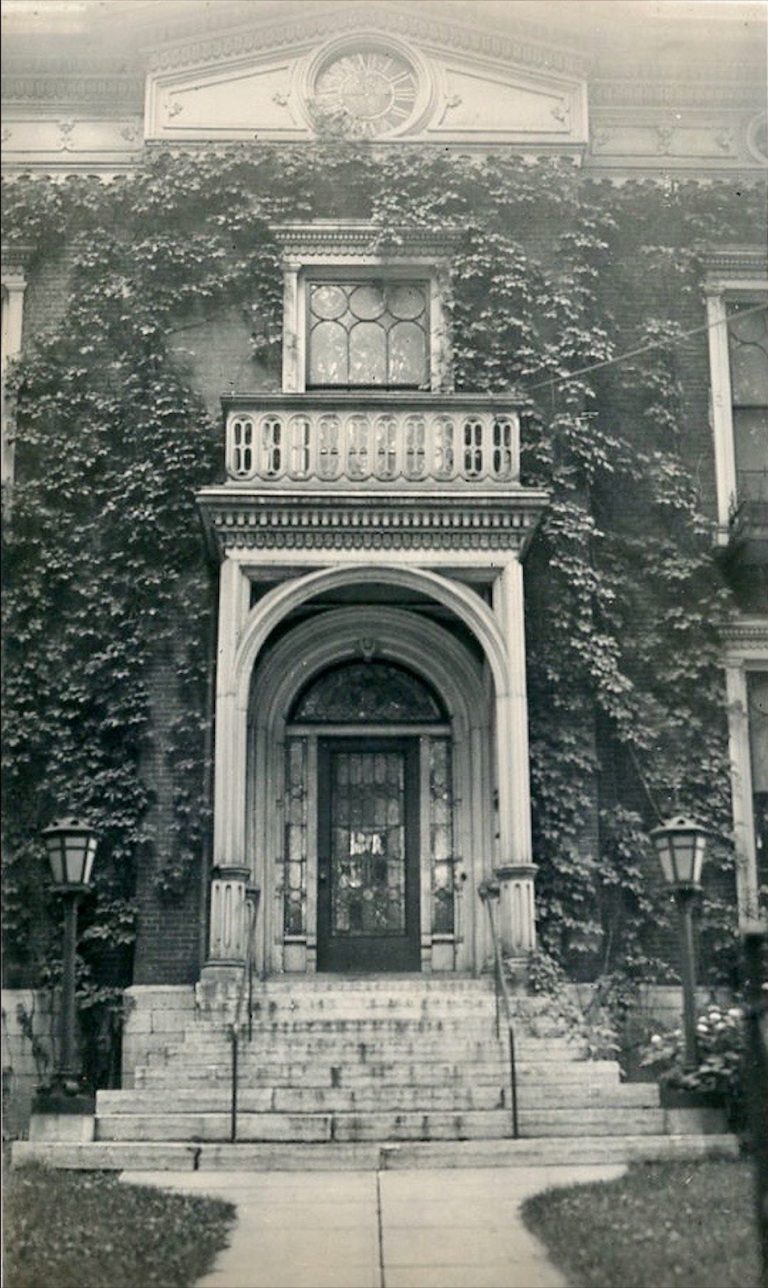

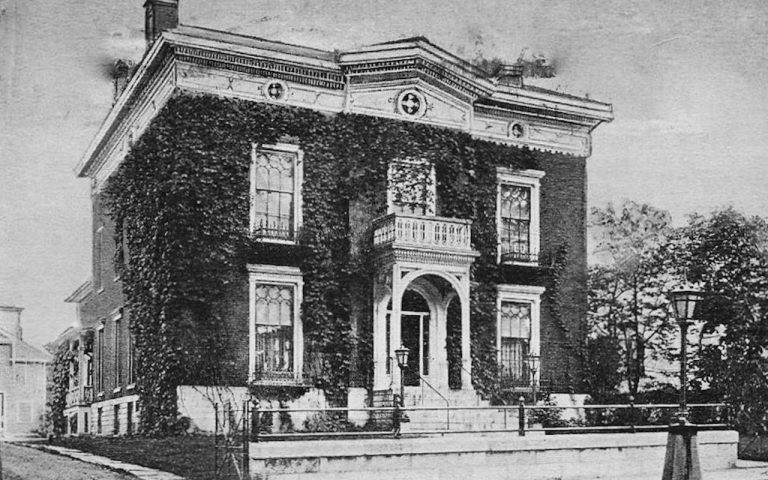

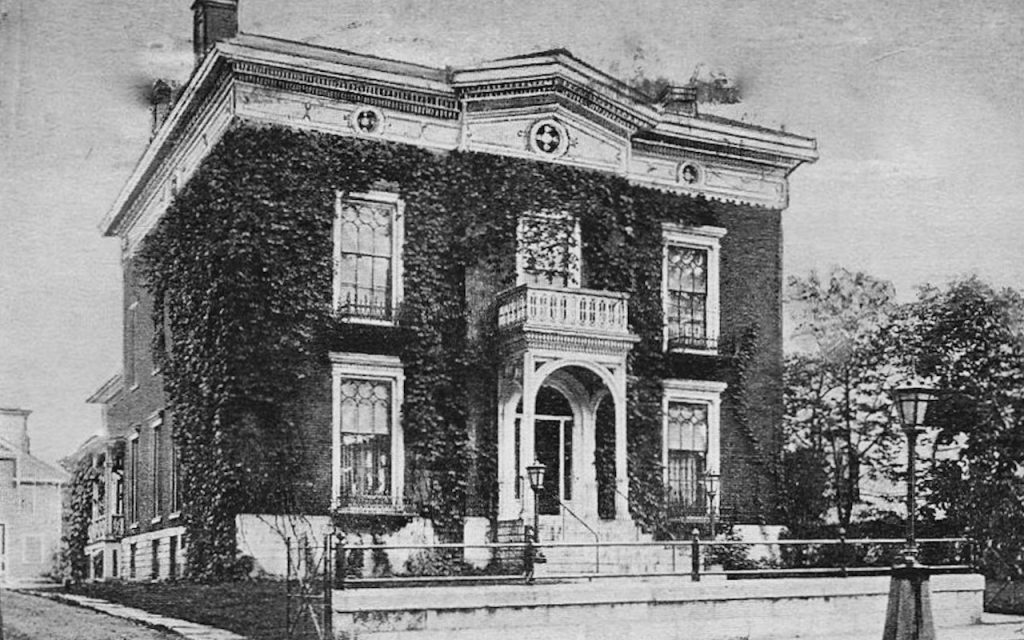

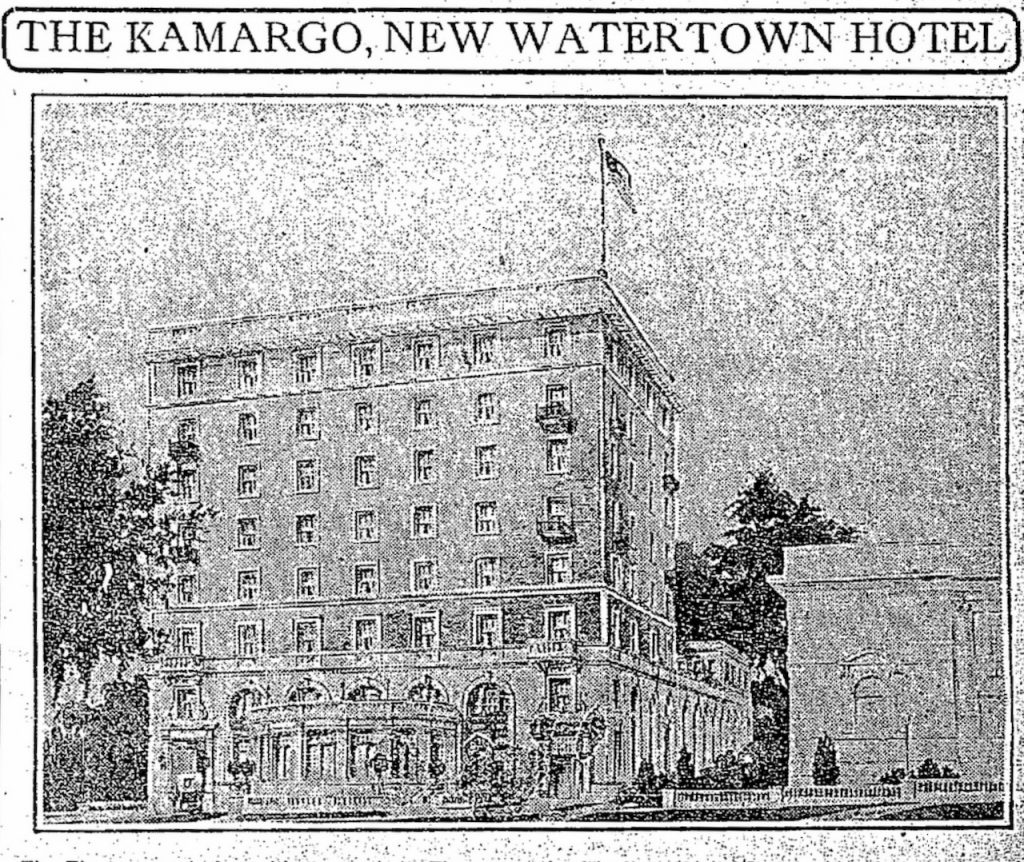

One of the earlier palatial homes on Washington Street in Watertown, N.Y., was the Orville V. Brainard mansion. Although no definite date could be established for its construction, references to it as the Brainard address on Washington Street appear as early as the 1860s. Its history, as such, isn’t as well defined though the history surrounding it certainly is, as it later became home to the Elks Club in 1913 and then razed in 1919 for what was to be the $500,000 ($8.3 million in 2022 value ), seven-to-eight story Kamargo Hotel which would have redefined lower Washington Street.

Orville Brainard was born on January 4, 1807, to Dr. Daniel and Lorraine Hungerford Brainard. After his father’s passing at age 27—just three days after Orville’s third birthday—he was raised by his uncle, Orville Hungerford, and Betsey Hungerford, for whom he was named. Orville Brainard had long been associated with the Jefferson County National Bank as a cashier and had helped establish the Jefferson Woolen Company in 1836. The company ultimately failed and later became the Jefferson Manufacturing Company, which built its main stone building, four stories high, later used by the Dexter Sulphite Mill.

Most notable was Orville’s wife, Mary Seymore Hooker Brainard, who was sister to Major General Joseph Hooker of the Union Army during the Civil War, known as “Fighting Joe.” Hooker was well acquainted with the area and spent his summers visiting his sister in the Watertown region. After the war, parading citizens marched around the square with a band and fire companies, carrying lighted lamps and marching on various streets until it came to the residence of Mr. Brainard, where Major General Hooker was staying. The crowd called for Hooker with cheers, finally winning his presence on the front porch for an impromptu speech.

The New York Daily Reformer would report of the September 6, 1864 incident—

This speech was received with cheer upon cheer, for Gen. Hooker, when the procession returned to the square, where there was a brilliant exhibition of fire-works, consisting of rockets, roman candles, a bonfire, and a splendid pyrotechnic piece made by Mr. Gragger of our village, representing an illuminated star, over which was the word—“Union,”—and on either side “Sherman,” and “Hooker.”

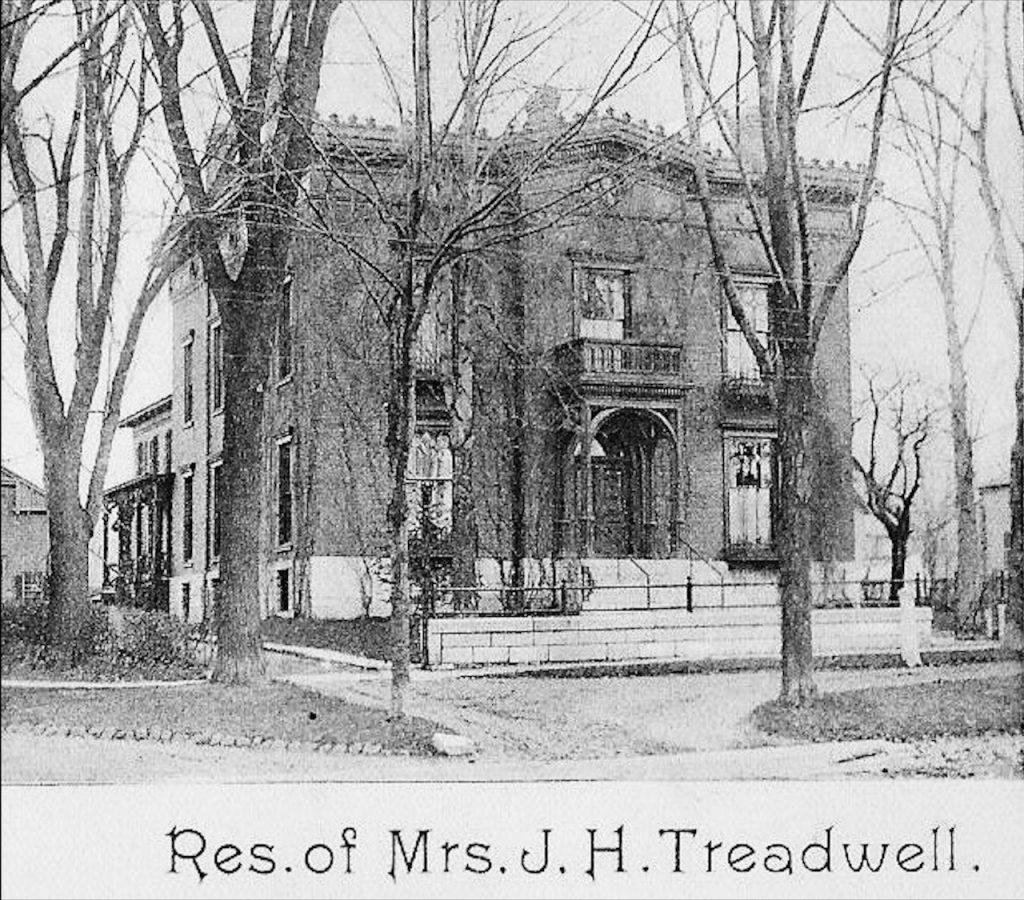

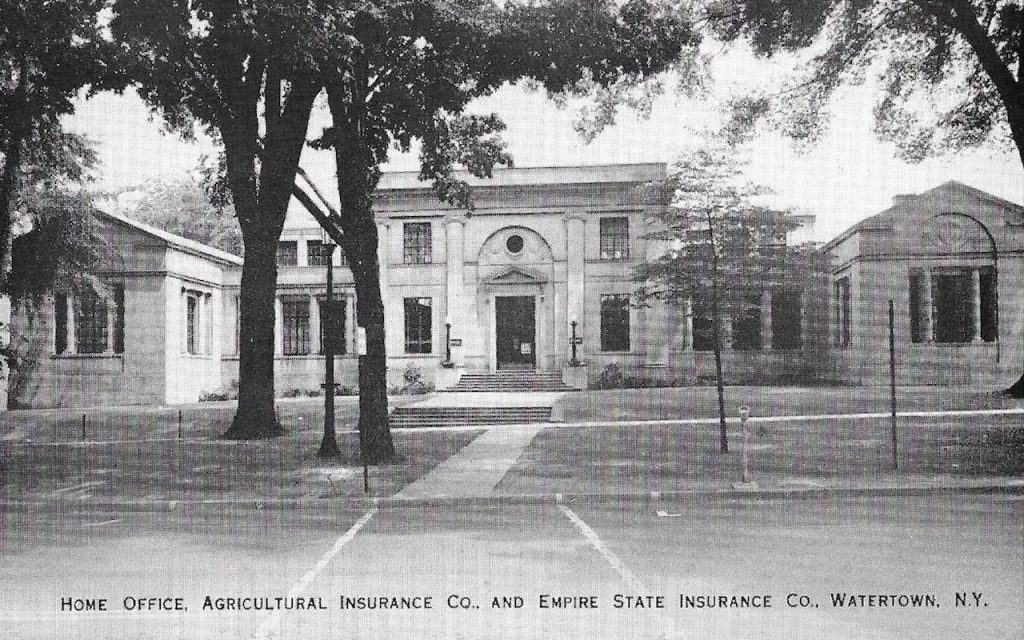

Orville and Mary Brainard had two children, one being Mary Seymour Brainard, who married John Henry Treadwell in late 1873. John, the son of a prominent and wealthy art dealer in New York City, was educated at Yale and is an author of several books. He had been visiting the area for some time before working as editor of the Watertown Post in October of 1873. Mr. Treadwell also wrote articles on occasion for the Watertown Daily Times but mostly found himself attending to an art room he had established in the Agricultural Insurance building next to the Brainard mansion where he and his wife Mary lived with her parents.

Unfortunately, John’s health deteriorated at an early age, and he passed away at only 38 years old. At the time of his death, he was a director at the Jefferson County National Bank. According to his obituary printed in The Times in January of 1883–

Our community were startled this morning by the announcement of the death of John H. Treadwell, which occurred at the residence of his wife’s mother, Mrs. (Mary) Orville V. Brainard, on Washington Street. He had been confined to the house for two months or more, and having suffered for a long time from a spinal difficulty, has been in weak and debilitated condition. To this was suddenly superadded an acute kidney difficulty, which hastened his death. His New York physician was sent for several days ago and, with his city physicians, has since been in constant attendance upon him.

Mr. Treadwell was the author of several books. One was “A Life of Martin Luther,” and another was “Pottery and Porcelain,” and both were well received by the public.

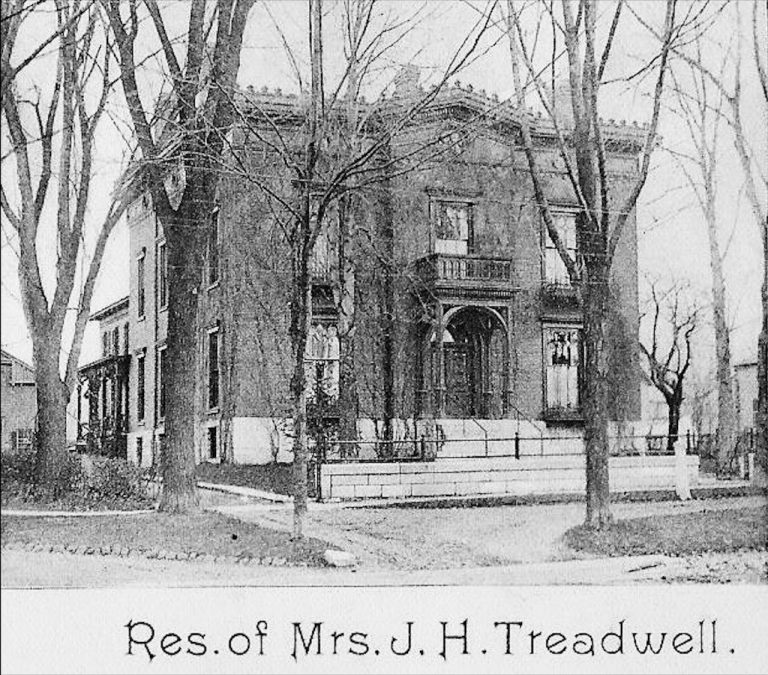

John’s wife Mary continued to live at the residence well after her parents’ deaths and was elected first vice president of the YMCA in 1903. A decade later, she sold one of the most coveted properties on Washington Street.

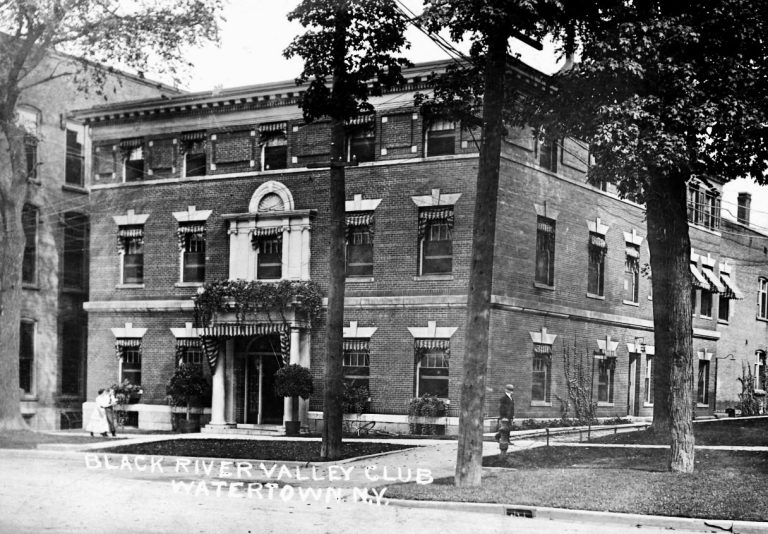

The Elks Purchase Mary Treadwell’s Mansion In 1913

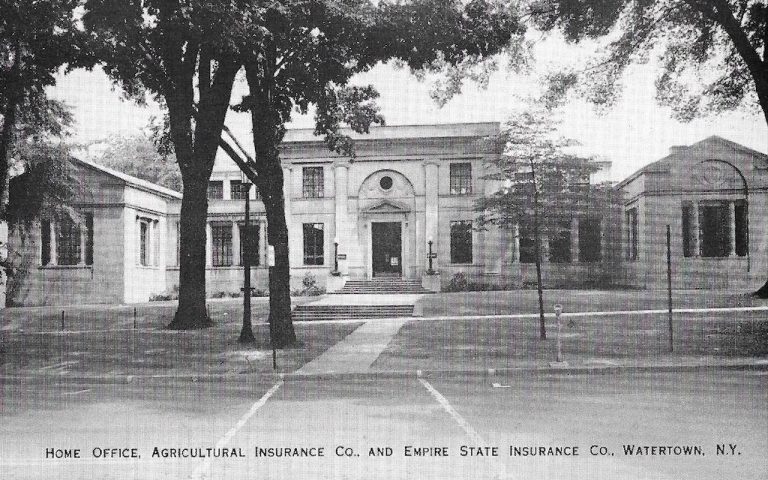

After negotiating a purchase price with Mrs. Treadwell, the Elks Club walked away with “one of the best homes in the country and one of the most desirable sites in Watertown,” according to The Times. Situated between the Agricultural Insurance Company’s old building and the Roswell P. Flower Memorial Library, the Elks Club was a prime location. It was rumored to be considered by the local Masonic Lodge for their new location.

The former Brainard mansion was remodeled on the interior, its basement to hold bowling alleys and a billiards room. At the same time, the attic was overhauled to become a large hall for meetings and dances, necessitating the club to literally “raise the roof.”

In November of 1913, the Elks Club finally moved into the residence. A general reception committee appointed Frank A. Empsall as chairman, and the building was opened for the public to inspect the club rooms. The Watertown Daily Times reported on November 11—

The rooms have been very tastefully decorated with palms. The long hall leading from the entrance to the back part of the house has many palms on either side throughout its whole length. Palms have been placed in both the larger rooms at the left and right of the hall in the corners and in front of the fire places.

The rooms are very elaborately decorated. The room at the right of the hall contains several large brown leather lounges, a brown piano and dark walls and carpet. The reading room at the left has light-colored walls and ceiling and the lounges and chairs are of light material.

In 1915, the Elks Club razed the old piazza (veranda) on the clubhouse in preparation for a new one. The old was found to be inadequate due to its size and style. The new one extended onto the side of the building toward the neighboring library grounds and was constructed by the local contractors Charlebois Construction.

In early 1918, with temperatures hovering around zero, an order for fuel conservation affected several clubs in the city. The Elks Club was the only one to close completely, though manager W. Scott Mattraw said the boiler would run enough to keep the pipes from freezing.

Mattraw, also the manager of the City Opera House, was later the first man drawn in the national draft held in Washington, D. C., with the number 322. The Times described the to-be Hollywood star in such a manner that “his general architectural plan is hardly that laid down as that of the ideal type of soldier.”

Within a week, the city was struck by an estimated 1,000 cases of Spanish influenza, and the Elks Club was to be used as a hospital. Whether or not Mattraw was disqualified because of his “architecture” is not known, but he continued to manage the club during its make-shift hospital tour of duty instead. Still, even that proved to be problematic per The Times, stating, “It is well known that a person of Mr. Mattraw’s general plan falls a victim to pneumonia more readily than one of a more Apollo build.”

With that said, and deciding to take no chances, Mr. Mattraw removed himself from the building, which operated as a hospital for five weeks into mid-November.

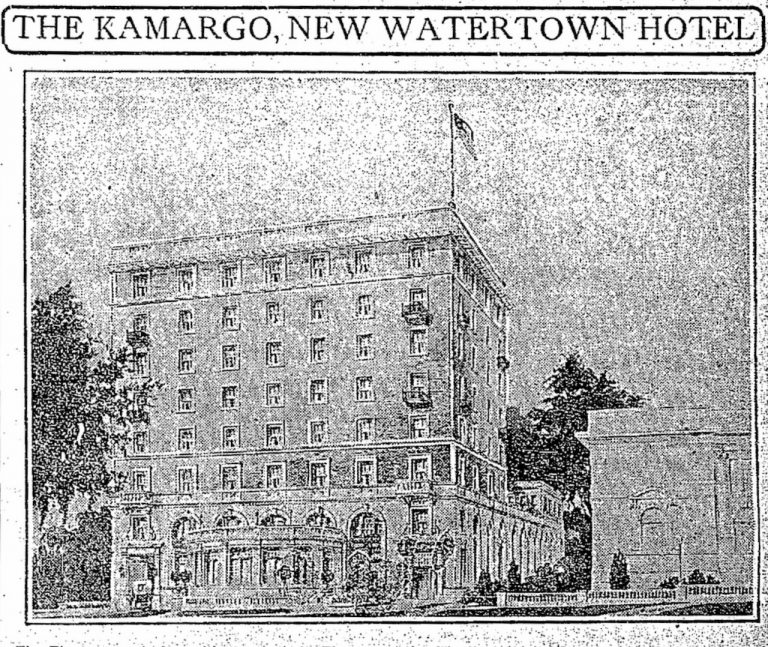

Elks Club Sold, To Be Razed And Kamargo Hotel To Be Built On Site

1919 would mark the beginning of the end for the building, as rumors swirled that the site was being eyed by a prospective hotel builder. The press decried the need for more hotel space in the city, and by early February, the Elks Club sold the house for $50,000 to an unknown syndicate represented by Frank A. Empsall. The Kamargo hotel was to have 200 rooms and cost half a million dollars to erect.

At the end of May, The Times reported that the former Elks Club would be razed immediately, and construction on the new hotel would begin within a month. The razing most likely prompted the photos taken here, as the dates denote 1919. Several days later, the Elks Club was notified to vacate the premises but given 60 days to do so.

The Elks were under the impression that they would have an option for their club to occupy the top floor of the new hotel, but they were informed unless they signed the release, the hotel would not be built. They would ultimately forgo the option and seek to occupy the Huested building on Stone Street.

At the end of July, the razing of the barn behind the former Elks Club commenced, with the clubhouse soon to follow. With the contract awarded at the end of August, the winning bidder was given 30 days to tear the old palatial mansion down. At the same time, Frank Empsall was looking to raze the Bignall Block on Washington Street, comprised of two blocks with one adjoining the YMCA, to build a new structure.

It was Empsall’s belief that lower Washington Street would become the central shopping district for high-class retail in Watertown, and he wanted to be part of it. Elsewhere, the Agricultural Insurance Co., located next to the now-razed former Elks Club, was said to have been quietly looking around to potentially build a grand new building.

The first signs of trouble with the Kamargo Hotel came at the beginning of October when the Karmargo Hotel Corporation postponed awarding the contract for construction and site excavation. The contract bids were finally opened and awarded to the lowest bidder, the Cowper Construction Company of Buffalo, and excavation would begin mid-November. And that’s how far they got until the project was postponed due to “abnormal costs,” with plans to resume as soon as possible. Contracts were extended for 17 months until June 1, 1922.

Instead of building a hotel, the Kamargo Hotel Corporation ultimately dissolved in February 1921. It was a victim of the short depression between 1920 – 1921, which lasted 14 months, and transferred the site to the Agricultural Insurance Company. As it’s often said, “The rest is history.”

Interesting Tidbit

The excavated ground for the Kamargo Hotel’s basement was deposited near the Court Street Bridge. When work commenced on the new double-decker bridge, a large fossilized tusk weighing slightly over 10 pounds and 16 inches in length was found amongst what was referred to as a stone dump by De Witt M. Carter, a well-known engineer and title searcher of Watertown.