First-Hand Accounts of Early Watertown Weather Phenomena

Below is the continuation of Cyrus T. Huntington‘s first-hand accounts of early Watertown, the majority dealing with weather phenomena. Huntington’s family moved from New Hampshire to the area known as Huntingtonville in 1803-4. The first portion of his accounts of the first schoolhouse and the solar eclipse of 1806 may be read here. The following is a portion of a very long letter to the editor published in the May 1, 1884, Watertown Daily Times.

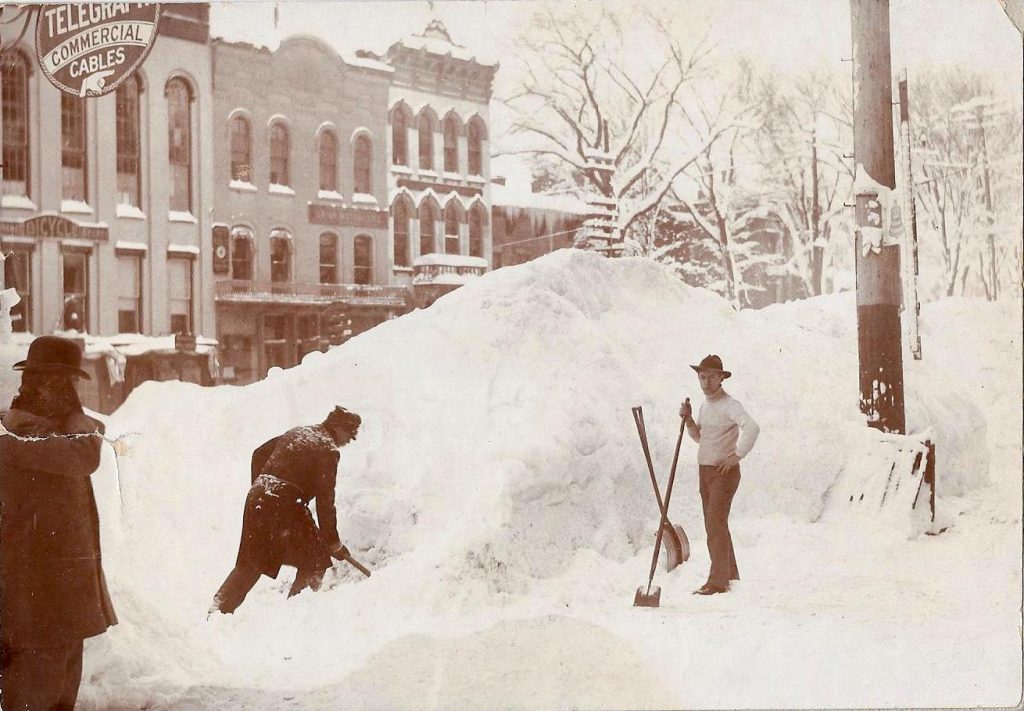

As there were no photographs from then, the ones here are either directly referenced in Huntington’s writing, such as the Great Flood of 1869, or used to give context. Note: the unit of measurement “rod” is the equivalent of approximately 5.5 yards or 16.5 feet.

The Earliest and Latest Spring

I will give you a few further recollections of seasons and weather, and then I am done. The earliest spring I ever saw was the spring of 1804. On the 28th day of March we ate boiled greens for dinner. At that time the leeks were up all through the woods, about eight inches high, and the maple leaves were as large as a dollar, and there was no frost after that, during that spring, to injure anything.

The latest spring, or the most backward I ever saw, was the spring of 1816. The 6th day June it snowed at intervals all day, and rained a fine cold rain or mist when it was not snow. The snow melted about as fast as it fell. On the Rutland, or Weaver hill as it was then called, the snow was two inches deep at night. Abel P. Lewis, of Black River, has told me that it was four inches deep in the north part of Champion, where he lived at that time.

About sunset it become clear and begin to freeze and continued to freeze all night. On the morning of the seventh the ground was frozen about one inch deep; the maple leaves were no larger than they were on the 28th of March, 1804; it killed all the leaves on the trees. On the morning of the 7th I helped to skin three of our sheep that chilled and froze to death the nights before.

In the morning their legs were frozen stiff and hard above their knees and gambrels. They had been sheared, the rain and snow the day before killed them. Two men froze to death the same night on Green Mountain. They were crossing over on foot, were overtaken by a snow tempest, and were both found dead.

The Greatest Snowfall – April 1807

The greatest fall of snow I ever saw in the month of April, fell the 1st of April, 1807. It fell in 24 hours 8 feet deep. The clearings were then small, the tree stumps were all standing; the snow covered the most of them. There was no wind, and the snow fell damp and lay as deep on the stumps as it was on the ground. It was a beautiful sight to look at.

The stumps had all disappeared, and snow columns stood all over the fields where the stumps were. Immediately after the snow a warm rain set in and took the snow all off. The snow and rain together caused the great freshet on Black River in 1807. It was long spoken of by those that saw it, of whom but few are left.

That freshet has never been equaled by any, unless it was when the state reservoir gave way. At that time, there was a man drowned a little above Whittlesey Point while endeavoring to secure a long pine tree or spar. At that time a lady was riding around on River Street; the surf came up and came nigh taking her with her horse into the river.

The Pleasantest Fall: 1829

The pleasantest fall I ever saw was the fall of 1829. Up to November 12th the weather had been warm, growing; the pastures were green. On the morning of the 12th at the first dawn it began to snow and continued until 4pm fast; it fell 15 inches deep. It then became clear. It froze in the night; in the morning the sun rose clear and warm, the snow melted fast and continued to lessen night and day; in three days the snow was gone.

From that time, November out, all of December and about half of January was as pleasant weather as I ever saw. The most of the time it was smoky; what used to be called Indian Summer weather. There was no time during the time above mentioned that the ground was frozen enough to prevent plowing green sod. I recollect reading in the paper that the boys at the Lowville Academy brought in live grasshoppers in January.

The Earliest and Latest Snowfall

I have seen it snow in eleven months of the year, July excepted. The most severe hail-storm I ever saw was in the forenoon of July 5th, 1821. It left marks of the hail on the buildings that were visible for years. The coldest time I ever realized in May began the 14th, 1834.

At noon it began to snow; it rained in the forenoon and at sunset it became clear; the snow was four inches deep. The early apple and plum trees were in blossom; maple leaves were nearly half grown; it froze hard in the night; the morning of the 15th wore a gloomy aspect; the maple leaves would crumble at a touch, and it was fair winter weather in point of cold.

In the morning there was hanging to my mill trough an icicle 4 1/7 feet long and three inches in diameter at the large end. Israel Lewis had a tub under the eaves of his house that held seven barrels and it was full of water; it froze over one inch thick of clear blue ice; it killed all the leaves on the trees. Judge Keyes was buried that day.

After this freeze the weather became warm; crops were excellent, in particular, corn. The winter following was the hardest I ever saw. On the 22nd of November the peppers and cucumbers were green in my garden. At 4pm it began to snow, at nine in the evening the snow was eight inches deep. That night there was a fire on the corner of Washington and Stone Streets, and a number of stores were burned.

The 27th the snow was three feet deep; it had thawed on the roofs of buildings up to this time, when it became too cold to thaw, unless it was by internal heat. From that time there was no dropping from the eaves of barns for forty-two days, commencing Saturday the 8th of January.

At this time the snow in the woods was called four feet deep. Saturday night the wind got into the south, and blew from that quarter fresh until nine Sunday morning, then it began to rain and continued about fifteen minutes, which caused the eaves to drip; then it turned to snow and blow for fourteen days longer, making, in all, fifty-six days without a thaw. After this we had a moderate thaw. When it was warm enough to snow the time was improved, but it was never too cold to blow and drift the snow; the temperature was extremely low all winter, and the snow was deep the first of April.

The Great Display of Red Northern Lights

The great display of Red Northern Lights (the greatest I ever saw) that occurred in the month of December, 1883 (the last number was indecipherable so I’m guessing 3 as he died in 1885) , and the red appearance of the heavens that occurred in the morning of September 5th, 1881, I looked upon with profound admiration in both cases. There were some among us that were frightened and thought the last day had come.

There were some points connected with the last mentioned light that I have never seen any notice of. The night of the fourth of September was the warmest I ever saw, my thermometer stood at 84º at midnight. At 9 in the evening there was not a cloud in sight. The stars shone brightly.

At 11 a dark vapor spread over the heavens; at 12 it was total darkness, and it was quite dark at 5 in the morning. At this time the heavens were the brightest red, which made it partly light; at 7 the orange had mixed with the red, and the heavens were a reddish yellow. It was nearly 8 before it could be seen where the sun was, and all the time there were no clouds.

The Most Fearful Thunder Storm

The most fearful thunder storm I ever witnessed occurred on the first day of August, 1820. At day-break in the morning, it was thundering in the west. It came up slow; at six it was overhead. In not more than twenty minutes the lightning struck thirteen trees within one mile of where I was, and two of them within thirty rods. I think there were as many balls of lightning struck the ground. It struck in the meadow near where I was, and tore up the sod, another one struck in the river but a few rods from me.

The thunder was more like a discharge of artillery than anything else. The flash and report were together. There was no building struck. it struck a large black oak tree that stood in an open field just south of the State road. It stood on the brow of the first hill going east. Capt. Whitney had run into an old barn that stood near the foot of the hill directly facing and not more than twelve rods from the tree. he stood in the door looking at the tree. When the lightning struck it, it tore the tree all in pieces; it did not leave a sliver more than teen feet high, and threw it in every direction.

Mr. Whitney told me that he saw the tree all in the air before a piece reached the ground. I was there a few days after and examined it, and I calculated that the tree was scattered over a good acre of ground.