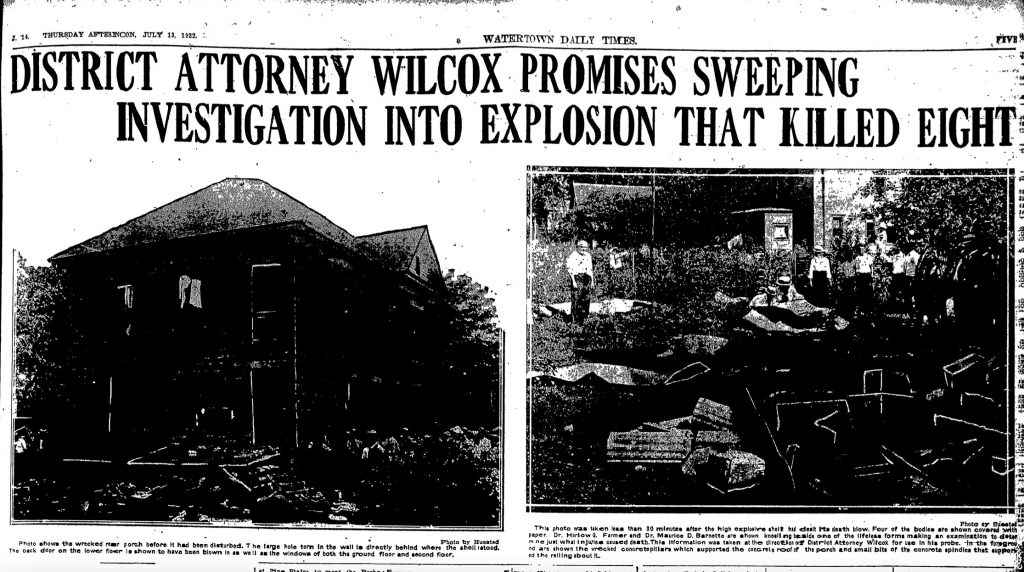

Explosion At 423 Dimmick Street Leaves 8 Children Dead In Watertown Tragedy, July 12, 1922

On a warm, sunny summer afternoon, eight children ranging from the ages of 8 to 16 gathered at 423 Dimmick Street in Watertown, N.Y., to play a game of croquet. The residence, a two-story concrete block building, belonged to Mr. and Mrs. Edward C. Workman, who rented the upper floor out to the William S. Salisbury family. The afternoon was an ideal one, especially for the children, only a few weeks out of school—but shortly after 3:00 pm, the tranquil neighborhood would be engulfed in a deafening boom, and a cloud of debris would slowly settle to reveal one of the worst tragedies in the city’s history.

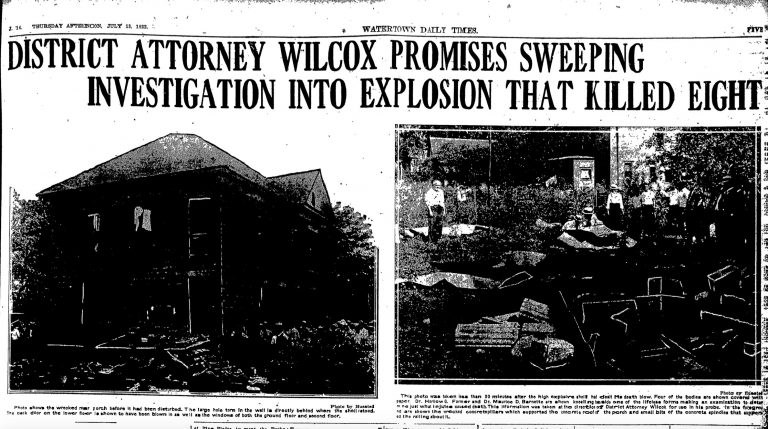

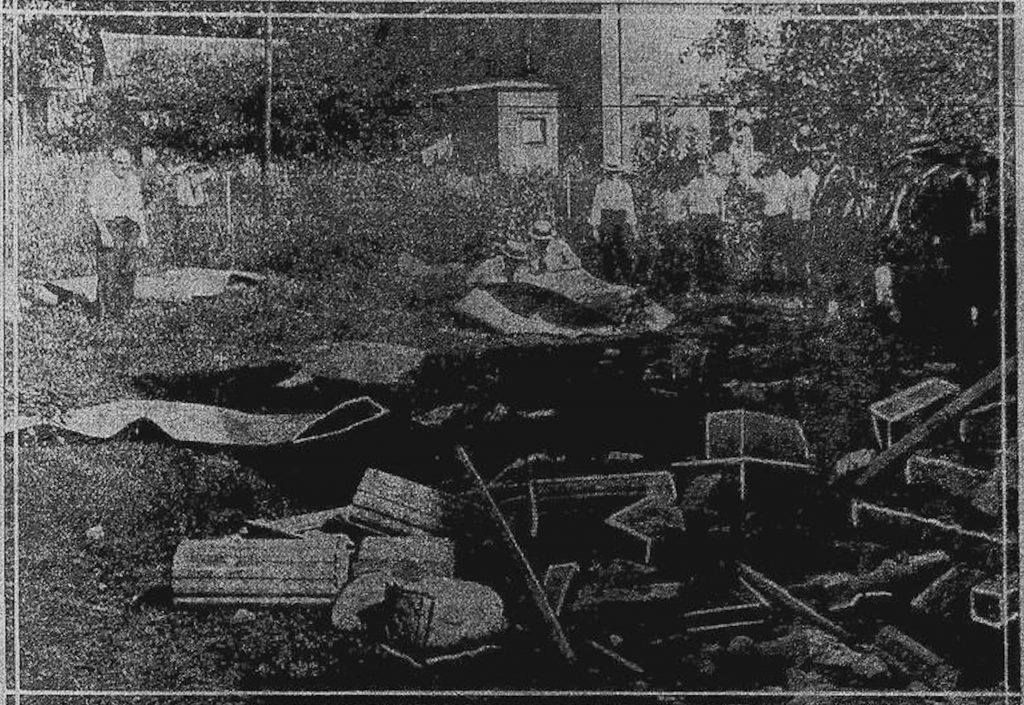

The explosion blew out the back portion of the house and destroyed cherry and apple trees in the backyard. A piece of debris struck an individual a quarter of a mile from the scene on their right hand, and an attending doctor initially believed it may have been broken.

According to the Watertown Daily Times, which rushed two reporters to the scene–

Windows in houses within a radius of two blocks were broken by the explosion. It is said that the bodies went up in the air for about 50 feet. This is according to witnesses. The entire area in the rear of the houses, about 100 yards in diameter, was completely shrouded in a deep black hue. Windows in the Mullin Street School were completely shattered. At about 3:35 pm, it was said the back of the house was almost ready to fall in.

Attorney Charles A. Phelps was driving through Ten Eyck at the time, saw the explosion first hand, and was the first to reach the scene. Phelps stated that “the building gushed outward and upward.” In later testimony, another individual, Edwin R. Greene, who was painting 150 feet from the Workman yard at the time of the explosion, said a yellow-ish colored smoke hung over the backyard for a bit after the blast and that initially, three boys were still breathing, though badly mangled, when he came upon them.

For one Doctor called to the scene, the discovery was especially tragic–

Dr. Edward W. Jones, father of Vivian Jones, aged 7, the youngest child who perished, was in his office in the Woolworth Building attending a patient, Lieut. George W. White of Madison Barracks, when a telephone call informing him that his little girl had been burned was received. Taking Lieut. White with him he proceeded to the accident. Even upon his arrival he did not know that his daughter was there, and lifting one of the coverings, he saw her, recognizing her by a small plaster he had placed on a bruise on her leg. The mother was at home when the explosion occurred.

As difficult as it was for Dr. Jones, he would quickly attend to the others, best he could, and then the families. Lieut. George W. White tentatively identified shell fragments as being from a 75mm projectile that was thought to have been brought back from France by Edward C. Workman.

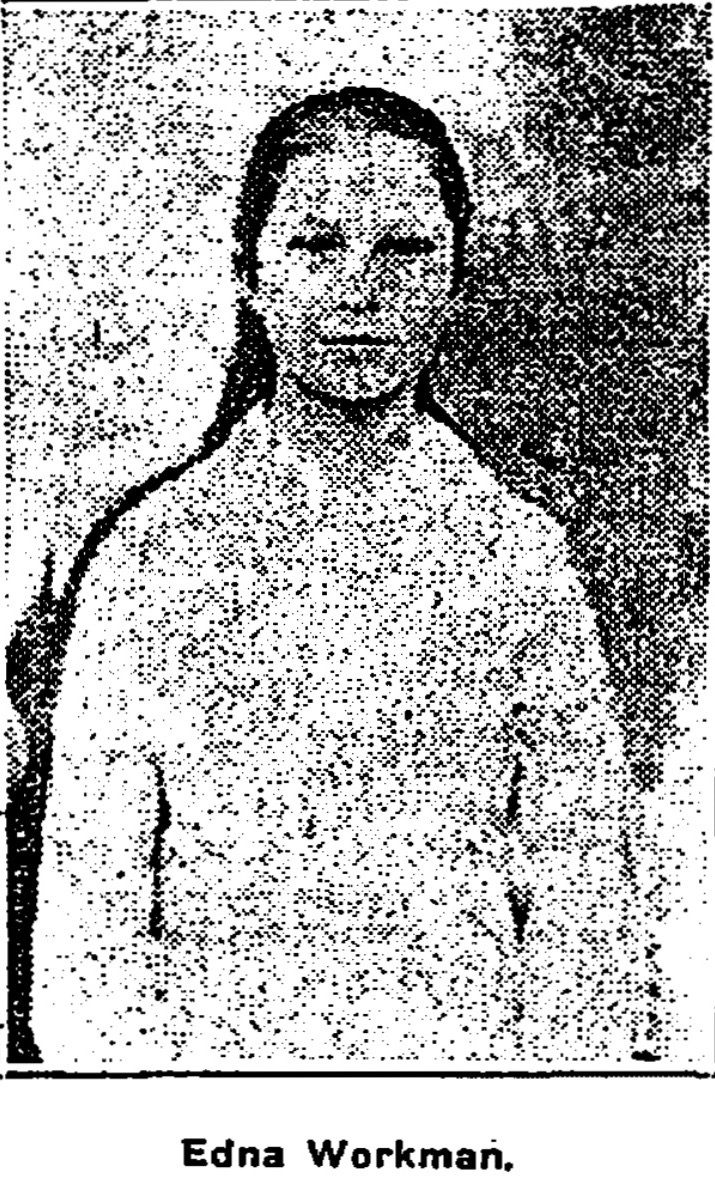

Workman himself also had the inevitable task of identifying two of his children, amongst the dead, which included several dismembered by the blast. The deceased included Sarah Barden, 10; Olin Brown, 10; Anson Workman, 13; Edna Workman, 15; Frances Wiley, 14; Monroe Salisbury, 16; Vivian Jones, 7; and Donald Horton, 14.

The ensuing investigation found the shell had been picked up two years prior in Pines Plains (later Fort Drum) by one of the victims, Monroe Salisbury (other reports mentioned his mother), and stood on the back porch of the address owned by Workman. Monroe discovered the shell on a berry-picking expedition with the Workman family and Anson Workman, who was one of the berry pickers that composed that party made up of the Workman and Salisbury families, requested that the missile, estimated to weigh 175 lbs, be taken home as a souvenir.

The shell was thought to be a dud, and, according to Mrs. Workman’s testimony, it was less than a month before the explosion that she had personally knocked it over and dropped it to see if it would explode, and that nothing happened. Though it was thought that perhaps the shell was stricken by one of the children while playing croquet, the investigation, particularly from Mrs. Semper, who was working in her kitchen and looking toward the Workman yard–

In her testimony at this morning session of the inquest she told of watching the children at play. Monroe Salisbury, 15-year-old son of Mr. and Mrs. W. L. Salisbury, occupants of the upper floor of the Workman house, had set up a croquet set for the younger children, testified Mrs. Semper.

When he had done so he started to return to a shady nook where he had spread blankets and pillows preparatory to reading a book his father had bought him that day, but turned back from this quiet recreation to join in the croquet game at the invitation of the younger children, so testified Mrs. Semper.

An instant before the deafening blow rent the air, sweeping eight children to death, Mrs. Semper said, Salisbury finished his game and walked up onto the Workman porch. There he stood, said Mrs. Semper, about the middle of the porch and close to where it has been established the “dud” stood. Mrs. Semper saw the boy unbutton his white top shirt and swing it open. He then wiped the sweat from his forehead and when she last looked at him was wiping sweat from around his eyes.

At the same time, said Mrs. Semper, Edna Workman, 15, and Vivian Jones, 10, stood on the ground just in front of the north and directly in front of Salisbury. The Workman girl had cherries in her other hand. None of the children had anything in line of a mallet or other object that the shell might have been hit with. Just then, Mrs. Semper glanced down at her sink as she was about to begin washing dishes. In less than a second, she estimated, the explosion came.

The tragedy would begin a state-wide movement of people turning over souvenir shells and the Fire Prevention Bureau was ordered to watch for them in inspections. Dozens of shells were reportedly picked up locally by souvenir hunters at Pine Plains. The local police department would be criticized for dumping six large shells and several smaller ones into the Black River. After the Watertown Daily Times inquired with the Ordinance Officer at Governor’s Island, the commanding officer at Madison Barracks would be instructed to issue local authorities proper instructions.

Heat was also suspected as having set the shell off, but that was refuted by Major James K. Craine sent to Watertown by the War Department in Washington to help with the investigation. Major Craine recommended the only way to ensure the munitions disposed of in the river didn’t explode was to retrieve them. He also surmised that the shell explosion at 423 Dimmick Street on July 12, 1922, was a 155mm projectile.

Yet another theory as to what set off the shell was from an engineer who believed the porch wasn’t of the best construction, and it may have shifted, causing it to explode. This, however, was disagreed with by another engineer. The Army’s official investigation would finalize its report in late August, and their conclusions were interesting, to say the least.

No 75mm shells were found at Pine Plains, and the munition that exploded was most likely a 155mm shell for a Howitzer from the 106th Artillery Unit from the Buffalo National Guard. Six days were spent collecting numerous shells from Pines Plains, but no 75mm shells were found. Witnesses had described the shell brought to 423 Dimmick Street as nearly 2 feet tall. They concluded that Mrs. Semper did not see the explosion, and her testament admitted so and concluded–

It is our belief that in playing with the shell, which had been rolled and thrown about the place for about a year, that the spiral became unwound, the safety pin shorn off, and the Salisbury boy sat on the firing pin head which detonated the upper and lower booster charges of the shell.

Some of this conclusion was likely based on testimony from Dr. H. G. Farmer and the condition the Salisbury boy was found in.

Tragedy Was Not The Last Of Its Kind In The Area

Despite the efforts to rid Pines Plains of unexploded munitions, as well as the neighboring towns turning over their numerous souvenirs found there over the years, it would not be the last such tragedy. In January of 1937, a 9-year-old Philadelphia boy, George L. Washburn, was killed as a shell he found at Pine Camp was hurled against a pole and exploded, with pieces of shrapnel piercing his abdomen. He would die three hours later before a blood transfusion could be given to him or an operation performed. Incidentally, Dr. Harlow G. Farmer responded to the scene.

Another Shell Found At 423 Dimmick Street Years Later

32 years after the tragedy at 423 Dimmick Street, another World War I shell, similar to the one that exploded on July 12, 1922, was found in the attic of the same residence. The 16-inch-long shell, three inches in diameter, was found by Mrs. Anna G. Workman’s niece, Mrs. Grace H. Giegerich, while cleaning out the attic in preparation for a sale. Patrolmen would take the shell and drop it into the Black River near the Court Street Bridge.