Trinity Church On Court Street And Watertown’s Dark Past With Its First Burial Ground

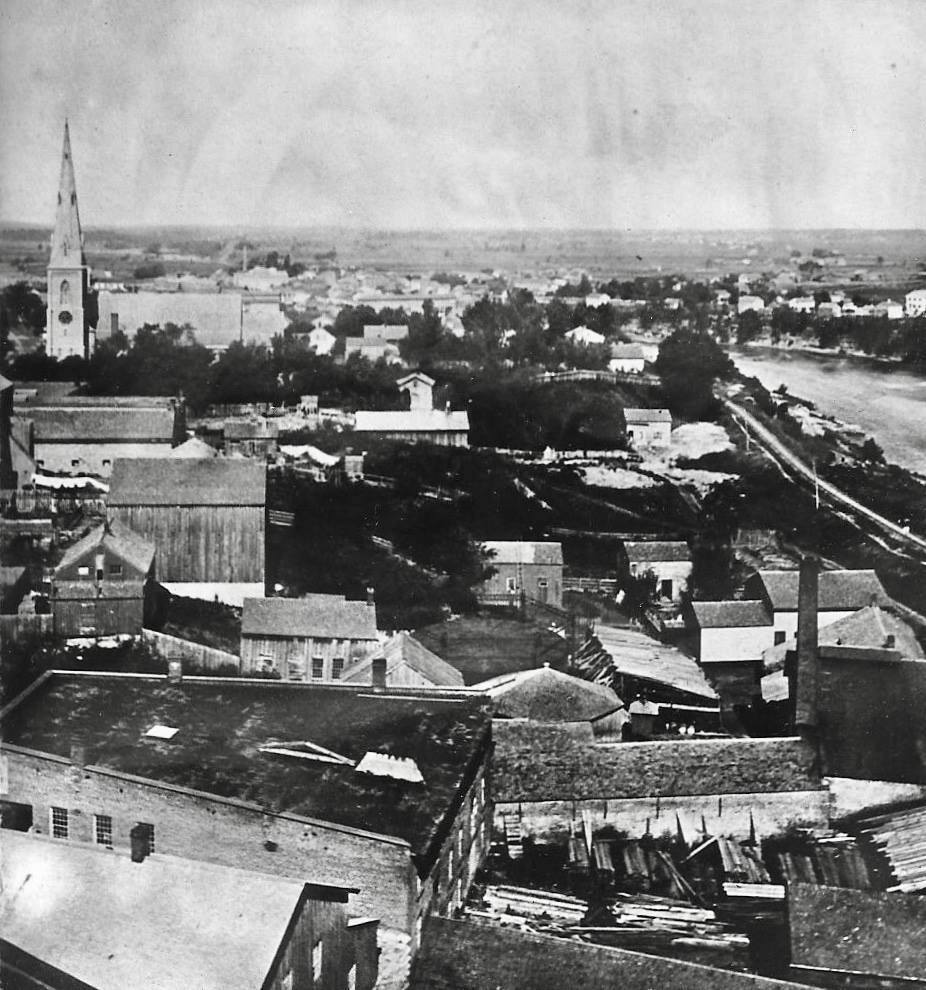

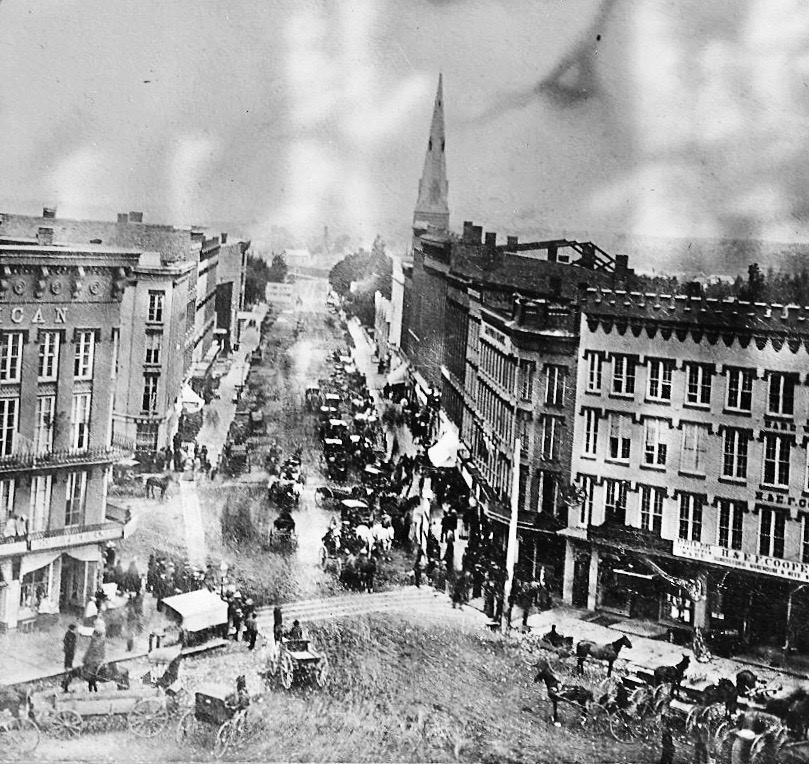

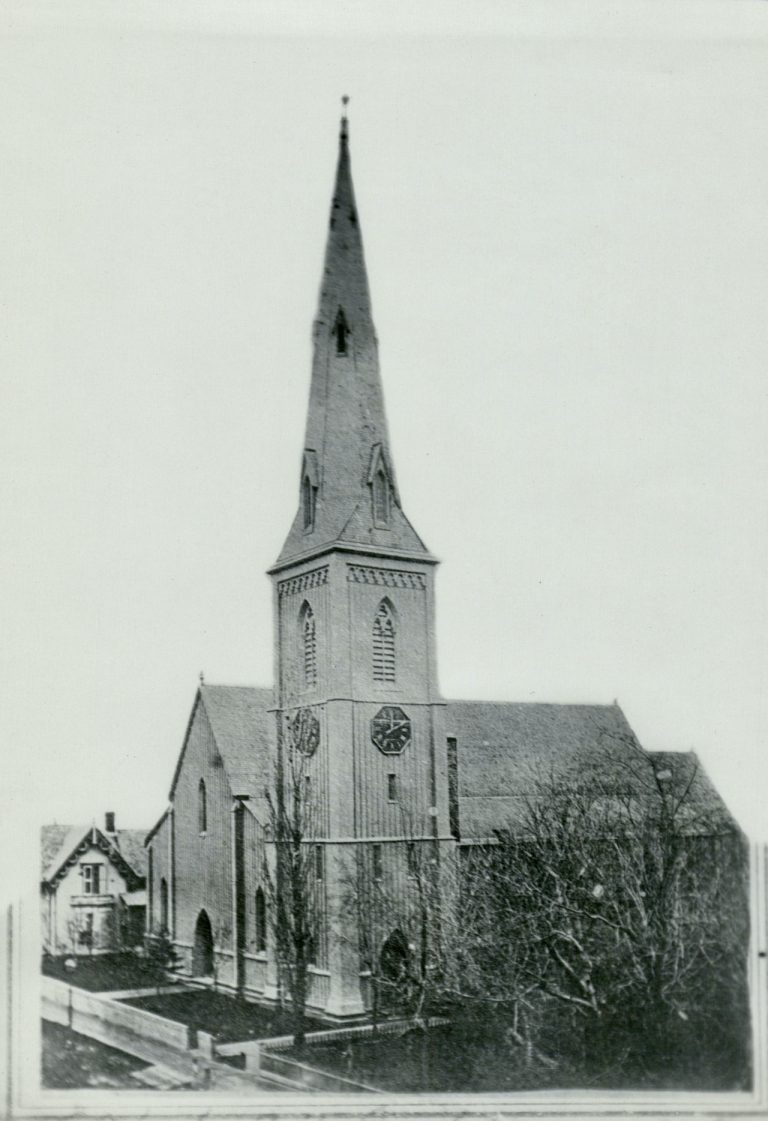

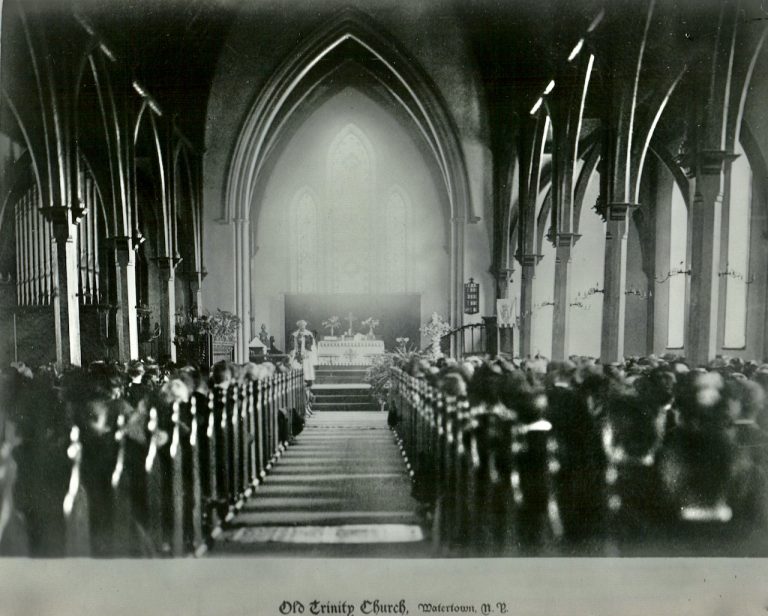

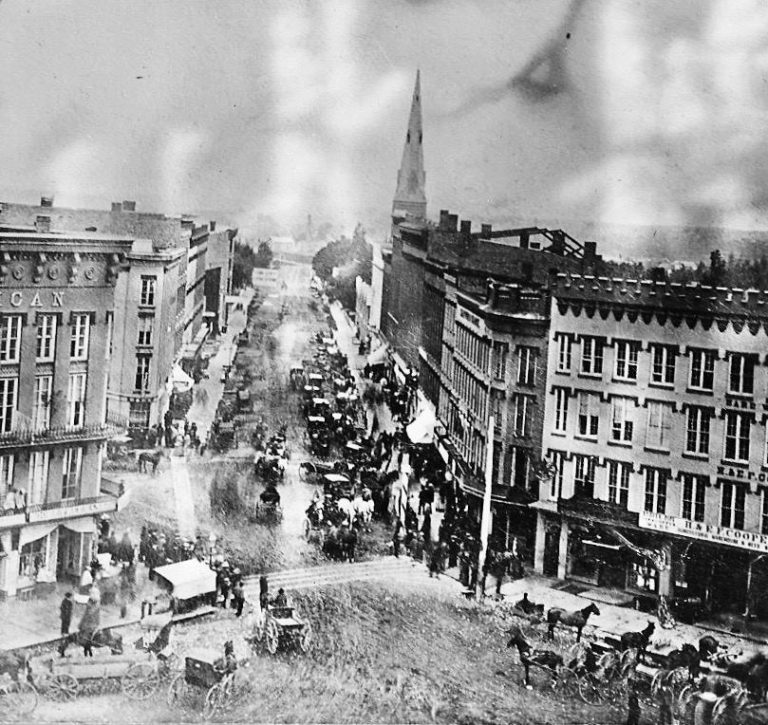

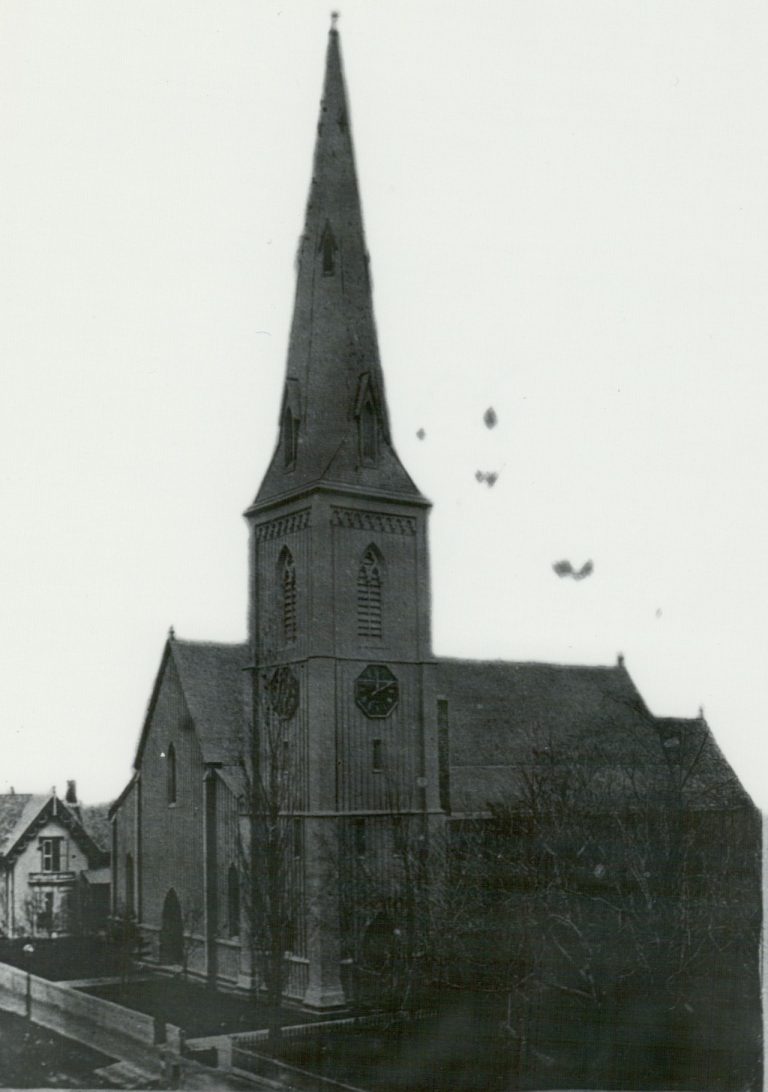

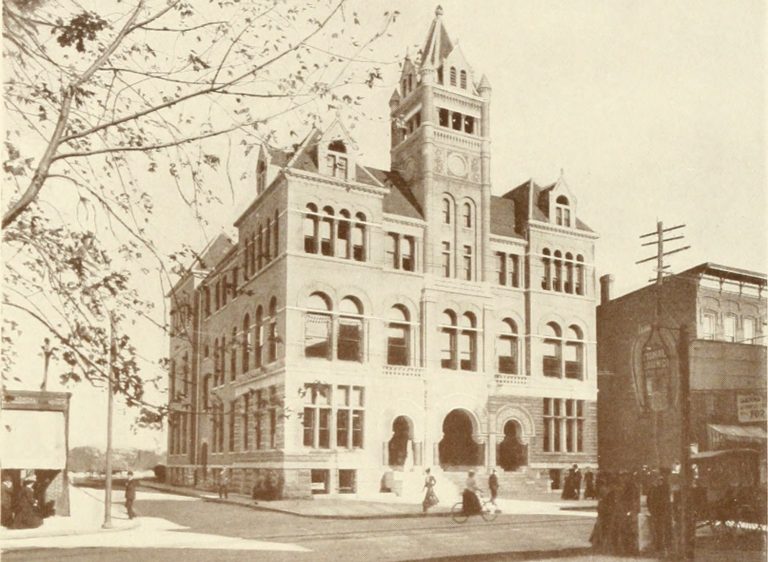

The first Trinity Church on Court Street was completed in 1833, but like many structures in the vicinity of downtown Watertown, it would be destroyed in the great fire of 1849. A new, wooden structure would replace it in 1850, with its consecration in 1851.

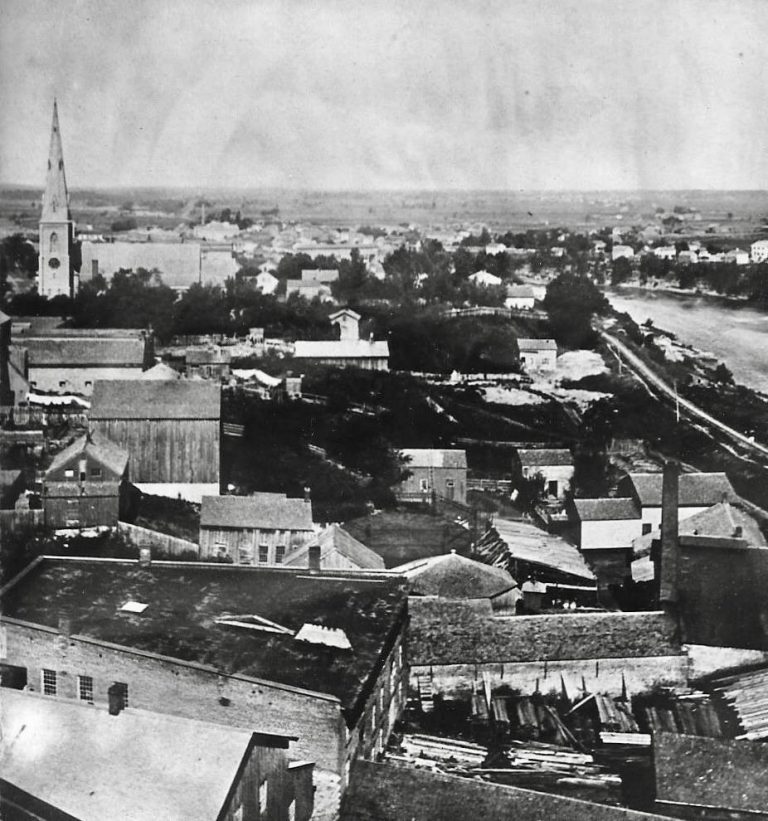

The land for what would be Watertown’s first burial ground would be conveyed to the trustees of the village by Henry Coffeen in 1819, an issue that would become problematic in 1888 when the Trinity Church on Court Street was abandoned for the new Parish House on Benedict Street from land given to the church by Esq. Anson Flower, brother to Roswell P., who also provided much of the funding for its construction. Construction of the current Trinity Church adjacent to the old Parish House would begin a year after the Flower brothers offered to build a new edifice.

While the city was technically responsible for the burial ground, it was referred to as the church’s cemetery in almost every facet of history, from books to newspaper articles. Even old maps would specify the grounds being in the churchyard. No reference was found made to who actually cared for the grounds, but all indication as to how the history played out, it appears Trinity Church may have assumed responsibility by mere proximity for the brunt of the criticism for what followed was placed squarely on the city of Watertown.

Before the land actually being given to the village of Watertown by Henry Coffeen or the church even being built, an interesting tale of two of the City’s earliest settlers, Jasan Fairbanks and Perley Keyes, confronting Samuel Whittlesey in 1812 over stolen money. As the story would play out, Fairbanks and Keyes had evidenced and threatened Whittlesey with a trip to the pearly gates if he revealed where the money was. Whittlesey finally confirmed that his wife was harboring the stolen money.

Whittlesey didn’t know that his wife had stolen some of the money from her husband. According to The Growth of a Century, written by John A. Haddock, Eli Thayer–

Mr. Whittlesey was led home and placed with guard in the room with his wife, until further search; and here the most bitter criminations (sic) were exchanged, each charging the other with the crime, and the wife upbraiding the husband with cowardice, for revealing the secret.

The guard being withdrawn in the confusion that ensued, Mrs. Whittlesey passed from the house, and was seen by a person at a distance, to cross the cemetery of Trinity church, where, on passing the grave of a son, she paused, faltered and fell back, overwhelmed with awful emotion; but a moment after, gathering new energy, she hastened on, rushed down the high bank near the ice-cave, and plunged into the river.

Her body was found floating near the lower bridge, and efforts were made to recover life, but it was extinct.

The telling of the incident implies that the land was already being used as a cemetery in 1812 and, at the time of the book’s edition published in 1894, the cemetery was firmly believed to have been part of the church. Likewise, the Watertown Daily Times would find records as early as 1800 for the plot being used as a public burial ground.

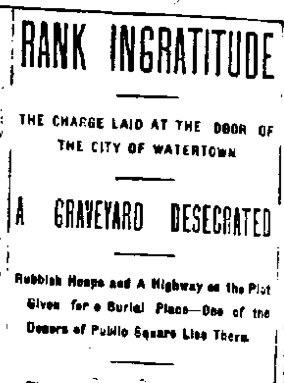

1894 would also be the year that the Watertown Daily Times would publish the outcry concerning what had happened to the burial ground, which would draw public protests. The account, first published on June 7, 1894, would be included in its entirety within The Growth of a Century and receive subsequent reprinting in 1902 in the Daily Times as the problem persisted with the headline “RANK INGRATITUDE: The Charge Laid At The Door Of The City Of Watertown. A Graveyard Desecrated.” The following is the excerpt from The Growth of a Century in its entirety–

After so honorable a record as is made in describing Brookside, it is humiliating to be compelled to notice the desecration which is now (June 1894), apparent in one of the oldest cemeteries in Watertown. We make extracts from an article published in the Daily Times of June 7, 1894:

When the land for the old Trinity church burying ground was conveyed to the trustees of the village of Watertown and their successors by Henry Coffeen, on February 12, 1819, (see Jefferson County deed book p. 355), it was definitely granted to them “so long as the same shall be occupied as a burying ground, the same now being used as a public burying ground” — (we quote the words of the deed.)

Of course the city’s title to the land, after it has been in any manner diverted to any other use, at once fails. In June, 1894, the writer went to those grounds to examine a date, when he found the graveyard nearly all obliterated, only six of the ancient tombstones remaining, the place used as a dumping ground for city refuse, a public highway running through the plot, and one of the old grave stones nearly covered with stable manure.

It was a pitiful sight, producing the most intense indignation. The Jonathan Cowan family are buried there, and their headstones and one other are all that are left—but they are open to the public road, liable to be rooted over by the swine from the streets.

The historical student will recall the fact that Jonathan Cowan was one of the three men who gave to Watertown lands for the Public Square, now so important and valuable to the city. But even that gift has been perverted from the uses contemplated by the donors, their conveyance reading that the said lands are granted for the use of the people “as a public mall (or open space) for the exchange of commodities,” that is, a place where any farmer might come with his hay or wood, or whatever he had for sale, and exchange or sell it. The writer understands that such a use of the Public Square would not now be permitted.

It seems that when the Trinity church property, which fronted the old burying ground, was sold and the new Trinity erected, the graveyard became very soon neglected, and in a measure open to the public. The fence doubtless became gradually obliterated, and the graves that are unprotected by iron railing at last were left wholly without defence (sic). The city officials, not heeding the law which would cause reversion of the property if used for any other purpose than a “public burying ground,” entered upon possession, and began to use the sacred place for storage purposes, and that abuse has been continued until this day.

The place is now a wood-yard, a storage place for stone and tools, and the dumping ground for street and stable offal. The city has built a public vault there for temporary use in winter when Brookside is inaccessible; the grounds have been levelled (sic), the graves obliterated and the legendary grave stones taken away and used in building, or otherwise destroyed.

It is hard to understand how such an abuse of a public trust could have been tolerated amongst an intelligent and Christian people such as are those of the city of Watertown. Those “heroes of discovery” who founded Watertown were anxious to protect their dead, as is evidenced by the terms of their grant. It is a painful subject, rendered more annoying when we reflect that even savage tribes revere and hold sacred for all time the places where their dead are buried.

The charges would be brought about by Mrs. Duford, a descendent of Henry Coffeen, who claimed the city had failed to comply with the terms of the deed gift, which gave the city title as long as it was used as a burial ground. As noted in the 1902 article–

The violation of the terms of the deed dates almost from 1888, when Trinity Church was moved from its site on Court Street. The article would then reference the then late John A. Hadcock article which had appeared in the Times eight years earlier.

When it came time to build what was the former City Hall on Court Street, the city chose to renege on its agreement, to even more significant controversy, and began relocating the burial ground’s contents to other cemeteries, specifically Brookside Cemetery and the Arsenal Street Cemetery.

Of course, this didn’t go well for the city either. During the urban renewal period of the 1960s, City Hall itself was torn down, along with other buildings in the area, to make way for Howland’s and other retail spaces. Additional remains were discovered along with a reportedly glass coffin with a rather well-preserved body inside, which is said to have disintegrated upon its opening.

According to an article in the 1966 Watertown Daily Times, when another claim to the land came up–

Records indicate the last burial made at the plot was about 1888. By 1903, all but one grave, that of Phineas and Emma Sherman, had been removed, with the remains being taken to other cemeteries. Besides the Sherman plot and the city vault, there was also a storehouse for the city property on the land. At the time, the city indicated that the grave and vault were evidence of the fact that the land was still being maintained for its original purpose.

The article would further note that in November 1905, the remains of Phineas and Emma Sherman, parents to the Wooster Sherman, who was an old banker in the city, and their four children would be removed to Brookside Cemetery, and the land’s usage as a cemetery ceased.

Though the debt between the city and Mrs. Duford was settled, much of the history of the city’s handling of the original burial ground and the entirety of urban renewal still seems rather unsettling. Walking down Court Street today, there’s a sense of time, a sense of place, a sense of loss, and a sense of injustice which makes its namesake all the more ironic.

1 Reviews on “Trinity Church – Burial Ground – Court Street (1850 – 1888)”

WOW!! I vaguely remember hearing about this back during urban renewal. Wasn’t the time buried bodies were found and moved when a building was tore down and another built. Does anyone remember the Sisters Mother House on Main St. ?

Yes, when the bodies were moved initially when City Hall was to be built they were moved to Brookside and Arsenal Street cemetery. I believe when City Hall was torn down and the site was undergoing preparation for new buildings the bodies that were discovered went to Brookside only (I’d have to double check.)