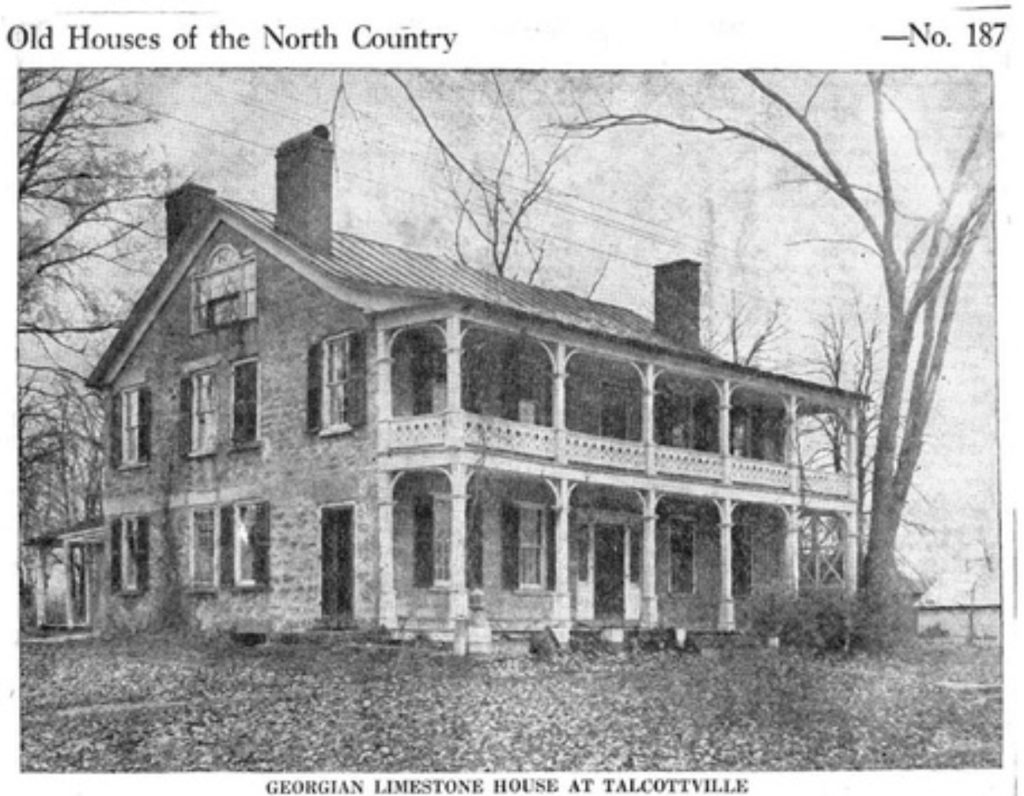

Talcottville’s Georgian Limestone “Edmund Wilson House” was once the Summer Home of the Famous Writer

One of the oldest stone houses in Northern New York (Lewis County, specifically) is the Edmund Wilson House, located on State Route 12D inside the hamlet of Talcottville. The Georgian Limestone was built in 1800 but inherited its current moniker from its most famous inhabitant, who wasn’t born until 1895, and whose family only used the property as their summer home. But Edmund made the place famous in his book Upstate: Records and Recollections of Northern New York, published in 1971, a year before Wilson’s death.

Construction began in 1789 and took four years to complete the 2 1/2 story home, though some sources state its completion in 1800. Like most towns, villages, and hamlets, Talcottville received its name from one of its earliest settlers, Jesse Talcott, who was born in 1775 in Middletown, Connecticut. According to David F. Lane‘s article in his series, Old Houses of the North Country, which further muddies the dates, Talcott came to the area in 1798 with his father, Hezekiah, and began construction on the home in 1880—four years prior the first documented, “Pioneer Christmas” in the area.

Lane’s article goes on to state—

The stone was hauled by ox-team from the banks of the Sugar river and it is said that it took four years to construct the house with exterior walls a foot and a half thick and interior beautifully arranged and finished. A handsome front entrance leads into a broad central hall, whence a most attractive staircase leads to the second floor. The inside woodwork is of the finest hand-craftsmanship and at the several fireplaces are white, wooden mantlepieces exquisitely wrought, each with a different ornamentation.

After Talcott’s death in 1846, he left the property to his daughter, who, according to Lane, “later became the second wife of the grandfather of Mrs. Edmund (Helen M W) Wilson.” The second wife willed a life use to an uncle of Mrs. Wilson, from whom Edmund Wilson purchased it. Sometime between these events, the home was said to have been used as a high-class tavern on what was then the direct route from Utica to Northern New York.

During his education at Princeton, Wilson befriended F. Scott Fitzgerald, who later edited two of his unpublished novels posthumously as Fitzgerald died at the relatively young age of 44. After graduating from Princeton in 1916, Wilson landed his first job at the New York Sun but soon became the managing editor for Vanity Fair in 1920. He later became a book reviewer for The New Yorker, where his literary criticism influenced many of the novelists of the day, though he was not above flogging some of the well-known works that have stood the test of time, such as H. P. Lovecraft and J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings.

Wilson’s own critical work, essays, and historical perspectives faired much better than his fictional work; his Memoirs of Hecate County was banned shortly after publication in 1946. Described by Amazon.com as an “erotic and devastating portrait of the upper middle class” with six somewhat related stories, it was considered obscene until 1959. Ironically, Wilson’s friend, Russian-American novelist Vladimir Nabokov, published Lolita in 1955. The book, unlike Wilson’s, was not banned by the US government but was by localities, their schools, and stores/libraries.

In a retrospective piece published November 2, 1986, in the Watertown Daily Times, staff reporter Carl S. Weiser wrote—

Mr. Wilson considered Talcottville home; in The Fifties he called Talcottville “the only place, perhaps, that I feel I belong.” The major theme of the book is just that—his coming home, leaving the intellectual and aloof world of critics and joining the world of the “common” people. As a reviewer wrote in The Watertown Daily Times, “Wilson demonstrates that he is the most approachable of men, and details his success at getting ‘down into the crowd.”

Weiser then asked, “But how does Talcottville remember Edmund Wilson?” The answers are about as complicated as the man himself, most knowing him as someone famous who lived there during the summer and had very little to do with others in the area. Apparently, the Wilsons never drove and required chauffeuring from place to place. There weren’t any trips to the local store across the street other than to use the telephone (Edmund was very frugal—even refusing to pay his income taxes), as they ate out every meal, henceforth having no need for groceries.

Then there’s the fact that Wilson married four times. His third, Mary McCarthy, like himself, was a well-known literary critic, yet the marriage lasted but eight years. It was said when they fought, he would disappear into his study and lock the door while Mary lit a stack of papers afire and pushed them under it. That’s not exactly the kind of spark of romance or flame that keeps a marriage afloat.

Former Lewis County deputy sheriff Dale W. Roberts, who was mentioned as one of the delinquents in Wilson’s memoirs, remembered Edmund as “…always well dressed… sarcastic and outspoken, intoxicated and usually grumpy. He would always call the cops on us. He was a grumpy old bear.” If it wasn’t the lawn, it was the porch that Wilson often had to tell area youths to get off from.

Some called him aloof, “bordering on snobbish,” and a man who generally kept to himself unless he had “literary types” over. J. Karl Zeigler told The Times that “Mr. Wilson didn’t much to he or his friends. ‘He wouldn’t speak to hillbillies like us.'” Yet, there were people like William L. Croston, Boonville, a Columbia University graduate, who remembered him fondly, telling The Times—

“I remember him as exceedingly interesting to talk to. He was brilliant, a good friend, with a marvelous sense of humor. He had a voracious appetite for anything he didn’t know. He liked to pick people’s brains. What strikes me most is that he was a man of omnivorous interest in almost anything.”

Marsha Reese, who managed the Talcottville General Store at the time of the article’s printing in 1986, recounted playing with Mr. Wilson’s youngest daughter, Helen. “I remember him putting on puppet shows. He used to give Punch and Judy shows for the Loomis sisters. I liked him.”

Before his death, Edmund Wilson was selected by President John F. Kennedy to receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his involvement in politics (President Lyndon B. Johnson later awarded it in December of 1963.) The following year, Wilson was awarded the Edward MacDowell Medal for his outstanding contributions to American culture in 1964.

Three years after Wilson’s death, the home was sold to retired army officer Michael Hearn and Mrs. Mary Hearn of Alexandria, VA, and Michael Hern, Jr., of New York City, who, like Edmund, was a writer. The home was listed for $90,000 by Wilson’s daughter, Rosalind. The mansion had been burglarized during the past year when she was away, with some valuable antiques stolen. As of 2024, the property is still owned by Michael Hern, Jr.