Alice Greenfield Murder Near Pulaski In 1875 Took Three Trials And The Victim Purportedly Speaking From Beyond The Grave

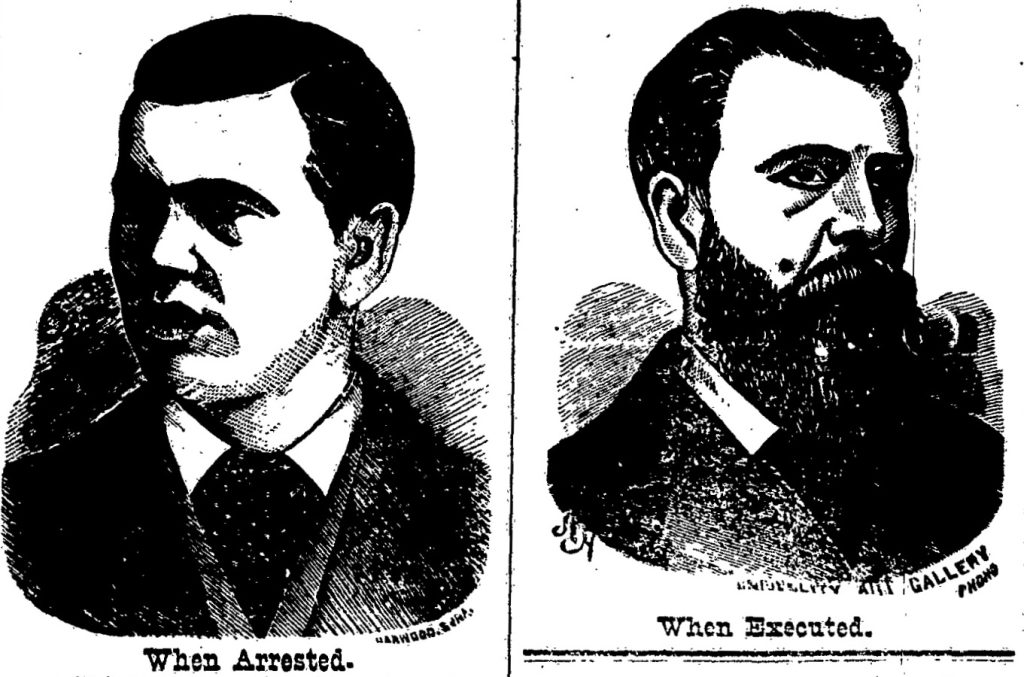

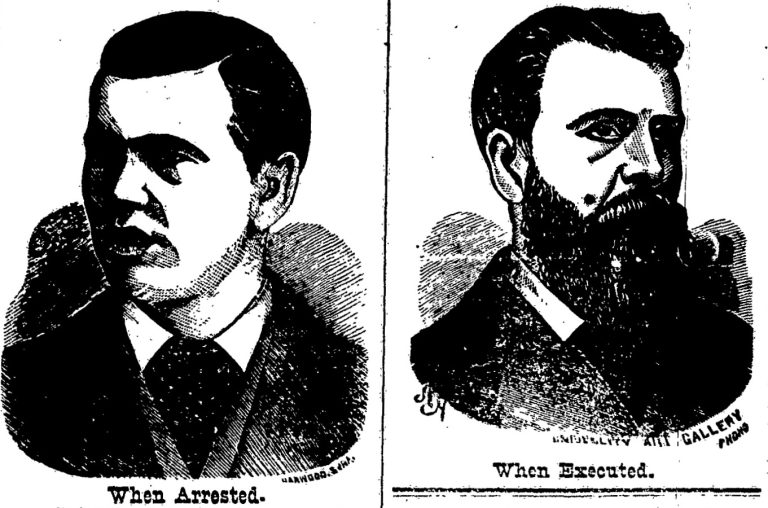

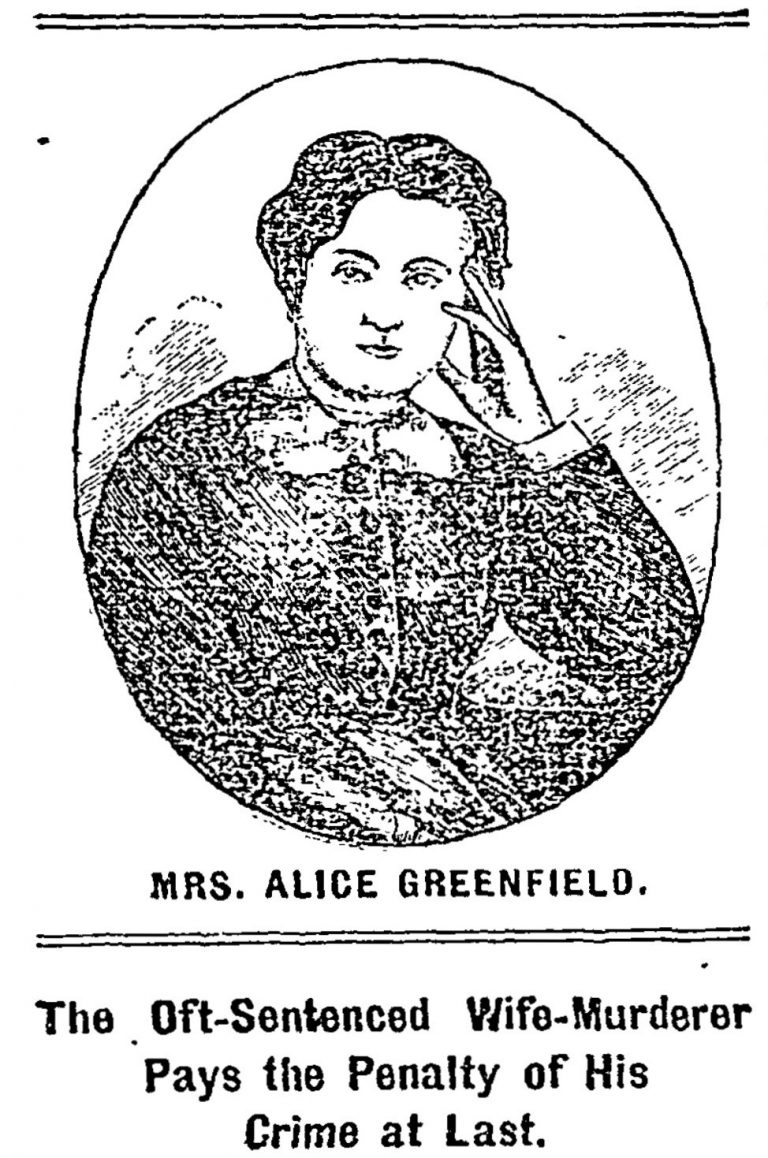

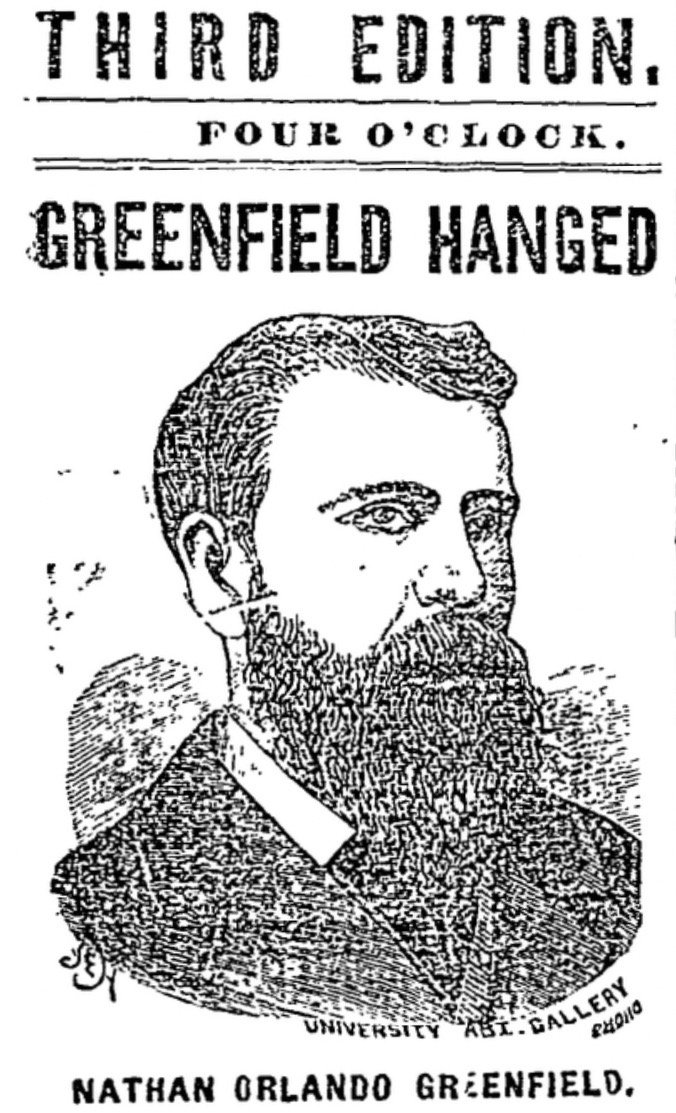

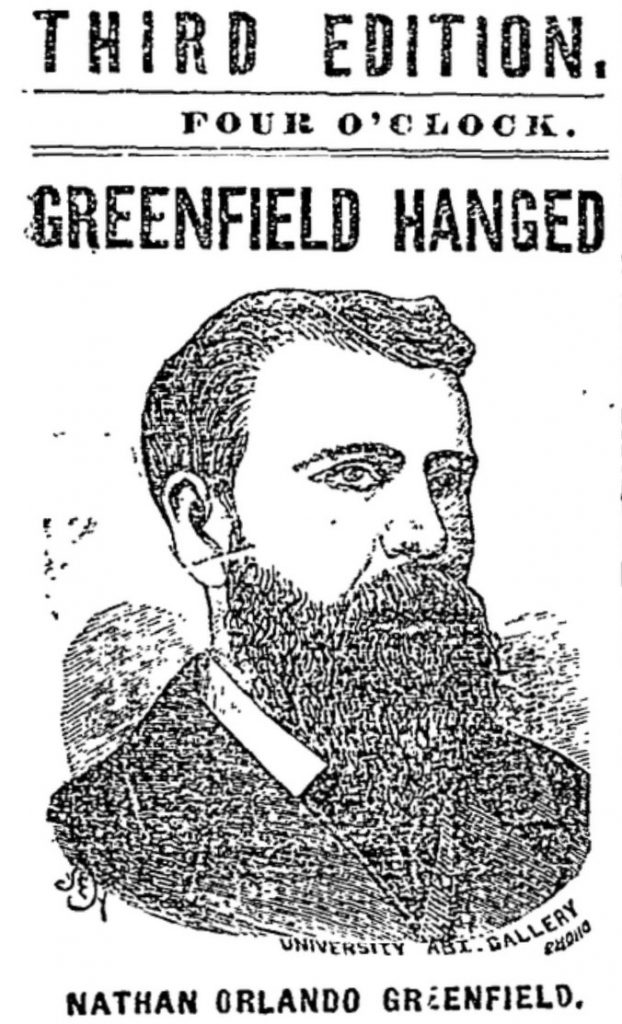

The Buffalo News called the Alice Greenfield murder in Orwell, N.Y., just east of Pulaski, “The most famous murder case this country has ever had” in an article published August 5, 1881. That was the date Alice’s husband, Nathaniel “Orlando” Greenfield, was the final convicted man to be put to death by hanging in Onondaga County, where the last three trials were held.

The brutal murder occurred in the early morning of October 21, 1875, but the trials, twists and turns – not to mention a bit of supernatural with the victim pointing her murderer out from beyond the grave – brought the case so much local attention, the last trial had to be moved to Syracuse from Oswego due to fear of bias from a general populace already very well aware of the crime.

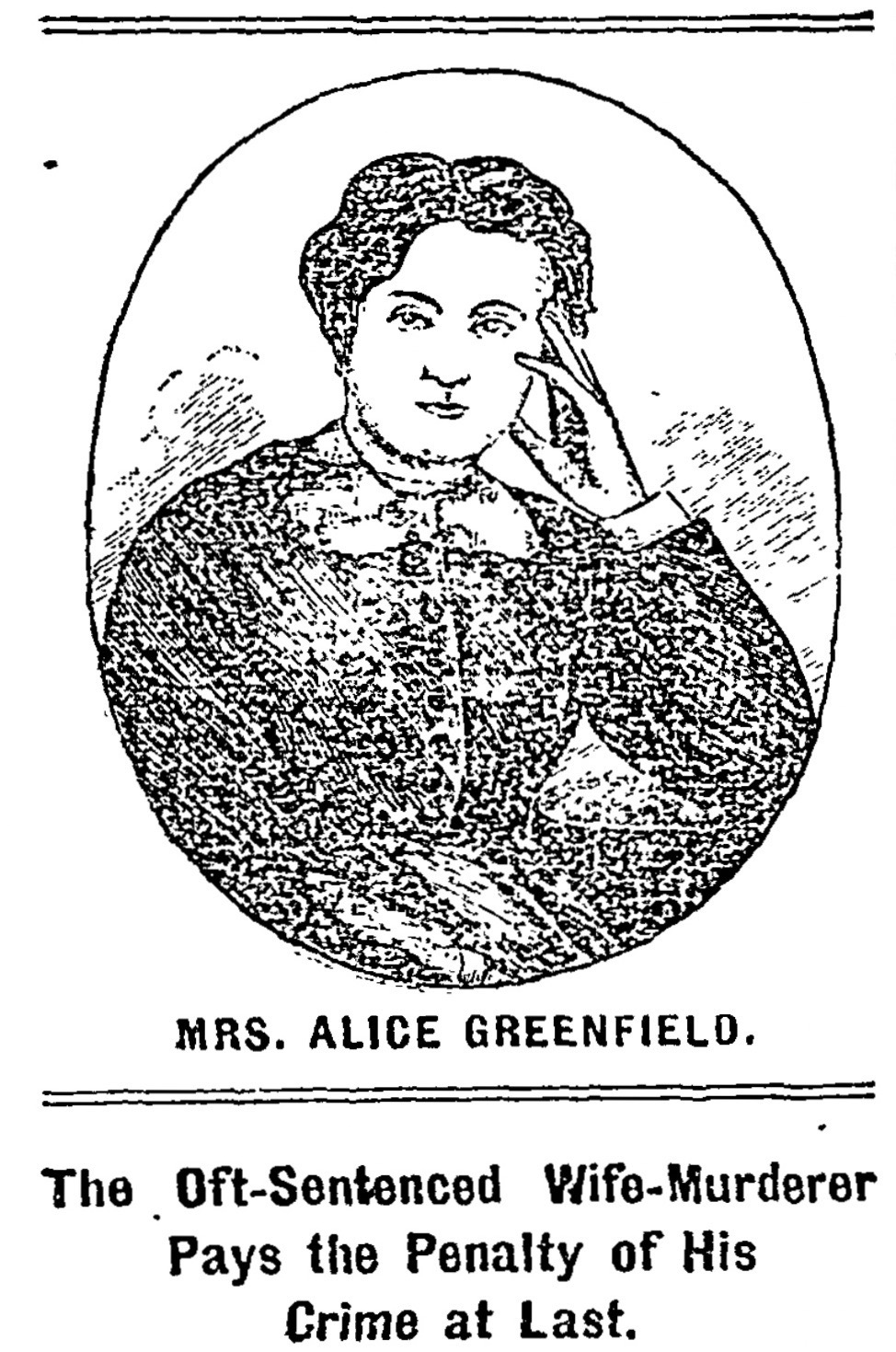

Orlando Greenfield married Alice Bloodgood nearly five years earlier; he was at the age of 21, and she was under the age of 15. The Watertown Daily Times stated that, in the ensuing years, Greenfield developed a “brutal character” and was both suspicious and jealous of his wife.

The summer before her death, Alice had, with her face bloody and clothes torn to shreds, applied to a justice of the peace for protection from her husband. Fearing her life was in danger, Alice had enough, and Orlando, through word of mouth, heard that she would leave him and his house that night forever.

The house they shared where the murder occurred was about three miles east of the village of Orwell on the Vorea Road. According to The Times, Orlando’s testimony was as follows—

On Wednesday he had been threshing grain all day away from home. During the day he heard that his wife would that night leave him and his house forever; after dusk he went home and from his own house to that of his father, directly opposite, telling the folks that some one was coming for his wife that night and he was going to watch; he watched and during the night saw a light in his house; he went to the house of William Grinnell near by and telling him that there was some one at his (Greenfield’s) house, asked Grinnell to go over there with him. They went together.

Greenfield was loth to enter, saying that he was afraid of being killed. Finally they entered and going into the bedroom in the dark stumbled against something, when Greenfield exclaimed, “My God, Alice is dead.” Greenfield testified that he went to his house between 11 and 12 o’clock that night and sat upon the edge of his wife’s bed and talked with her. It was 3 o’clock in the morning he and Grinnell went there and found his wife dead.

Turns out, Orlando, William and Alice weren’t the only ones to visit the house that night; more on that later.

The August 5, 1881, Buffalo News noted that the 19-year-old Alice was four months pregnant with what would have been the couple’s third child. When the coroner arrived that morning, the scene was described as—

The body had not been disturbed, and although many of the men who gathered about it had been in the army and seen death in every form, the sight chilled them. On the floor was the dead wife with nothing on but her night-dress, her throat cut from ear to ear, the jugular and windpipe both being severed, and the upper part of her head, near the crown, pounded to a jelly.

There were contusions of the skin about the neck and breasts, and everything to denote that the woman had not died without a struggle. On the floor, not far from the body, was found a hickory stick, covered with clotted blood and hair, and blood was to be seen spattered on the wall.In the pantry was found an ordinary jack knife, and on the large blade were spots of congealed blood.

Greenfield’s hands were subsequently examined under a microscope with traces of blood under his fingernails. He attributed it to an accident while helping his brother earlier. The Times wrote two days later, on Oct. 23, 1875, that the coroner’s jury, after a session of ten hours, rendered the verdict: “That Alice Greenfield came to her death from wounds inflicted by some sharp instrument in the hands of some person to the injury unknown, but the evidence taken the jury believes it to be her husband, Orlando Greenfield.”

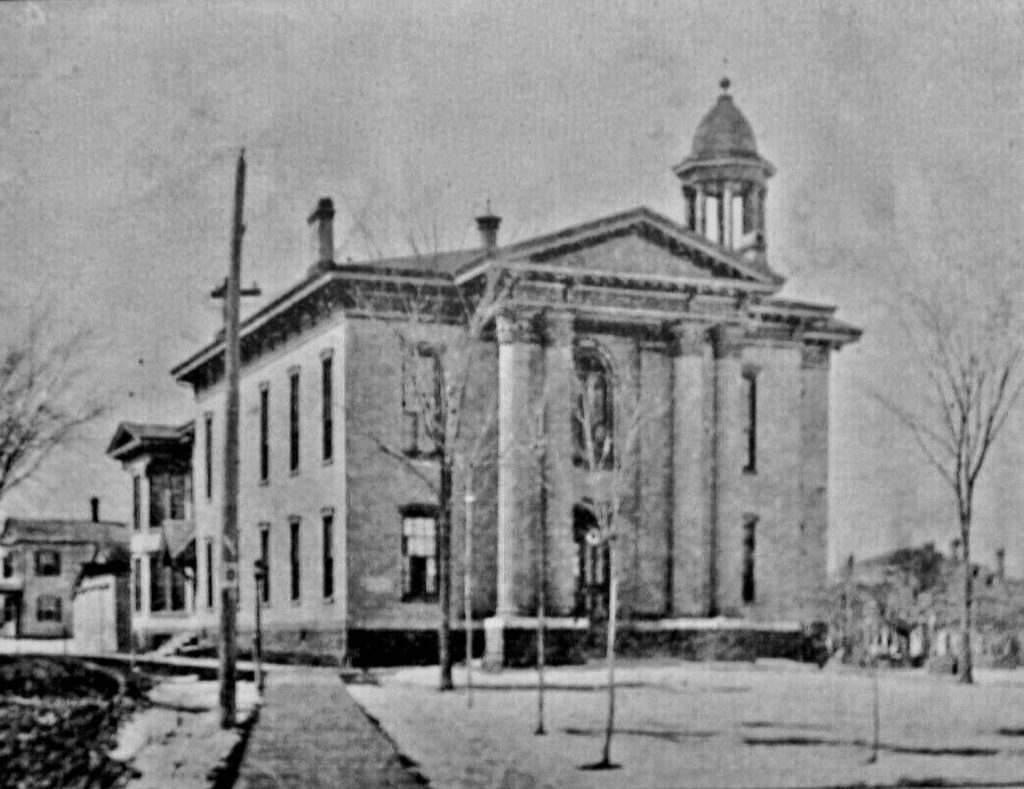

Coroner Lawton then issued a warrant for Orlando Greenfield’s arrest. Officer Dillenback complied with the warrant and Greenfield was placed in the jail at Pulaski, where he gave his testimony printed above. Greenfield retained former Judge Sylvanus Convers Huntington, described as a “brilliant lawyer” educated at Dartmouth who lived in Pulaski and once served as Oswego County Judge and was later elected District Attorney. “Never did a man work harder for another’s life,” was written of Huntington by the Buffalo News.

In October of 1875, shortly after the murder, Judge Huntington put out a warrant against Royal and Alden Kellogg, brothers, charging them with the murder of Alice Greenfield. The brothers were subsequently put forth before the two justices of the peace in Pulaski. Huntington had found a gun, which he claimed belonged to his defendant, Orlando Greenfield, which Greenfield said was stolen from his house and discovered missing when his wife’s body was found. The defense’s theory was that whoever stole the gun was connected to the murder.

The brothers were eventually let go, but it wouldn’t be the last time they were mentioned in the case and the disappearance of the gun remained a mystery through the first two trials – though later explained in a convoluted plot to show Greenfield’s innocence.

The First Trial

The New York Herald published in June of 1879 a concise overview of the first trial—

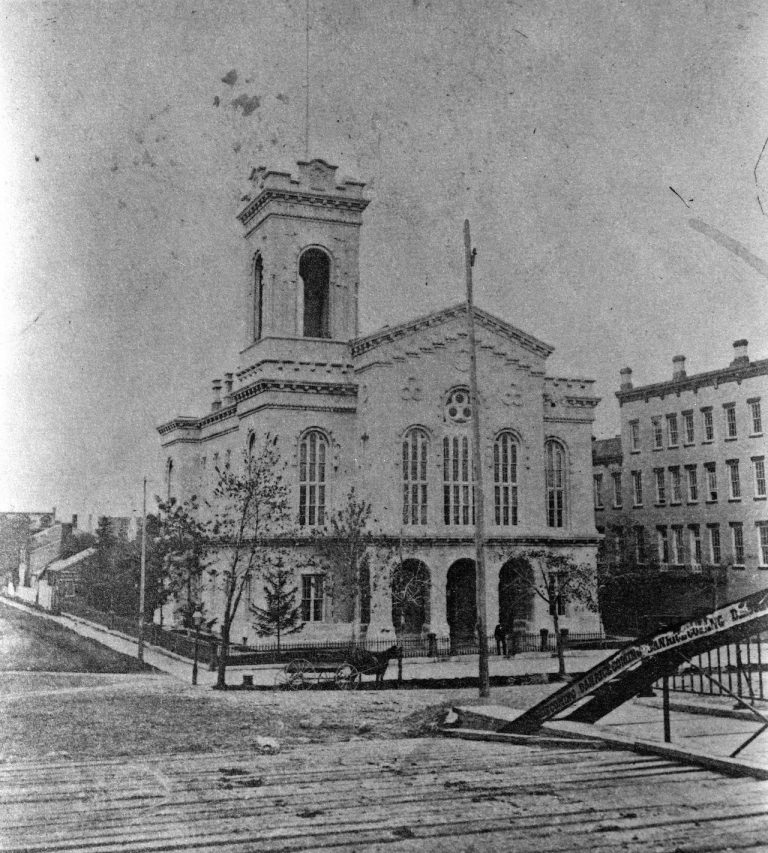

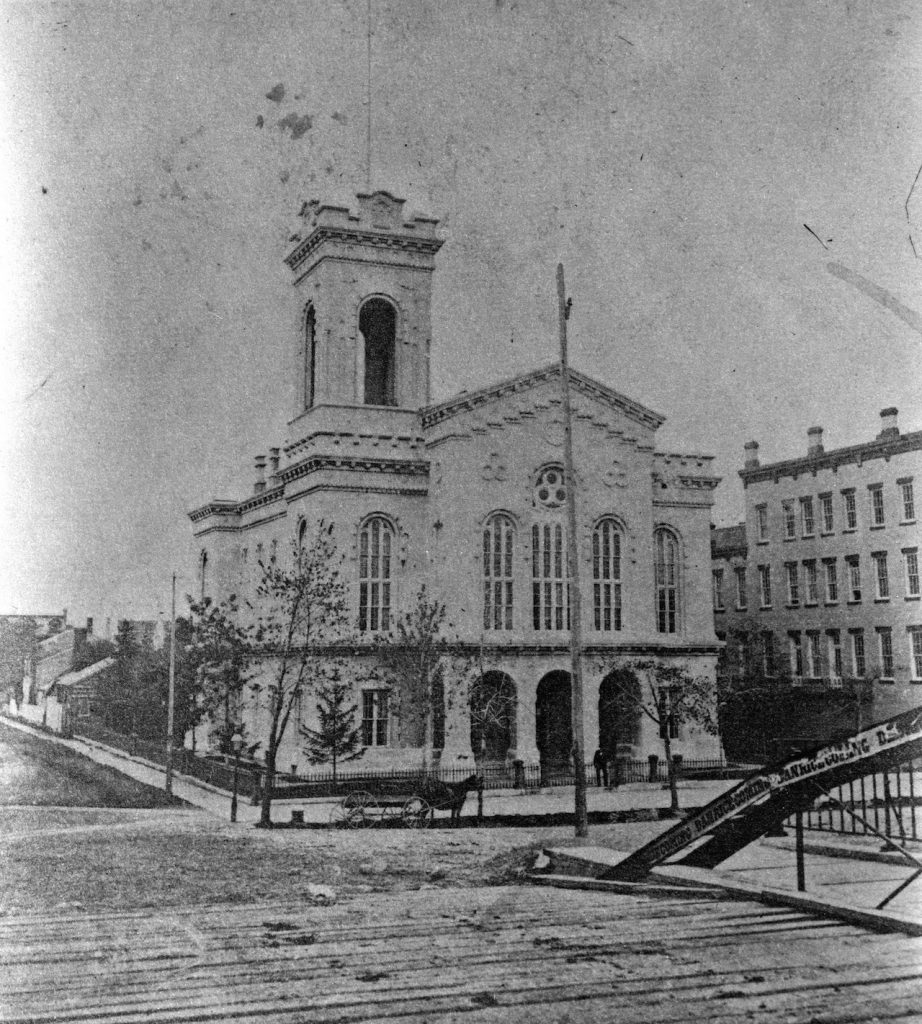

Greenfield’s first trial began in the court of Oyer and Terminer in the city of Oswego, May 25, 1876, before Judge Noxon, Judge of the Supreme Court. The prosecution was conducted by District Attorney Lamoree and the defense ex-Judge Huntington. Of the panel of 232 jurymen called 109 were examined before twelve suitable men could be chosen. On this trial the prosecution summoned eighty-two witnesses and the defense twenty-five.

The case went to the jury Saturday, June 21, at half-past nine o’clock at night. On the following Monday morning the jury came into court and announced their inability to agree upon a verdict. It was generally understood that of the twelve, nine were for conviction of murder in the first degree and three were for acquittal. The disagreement was a subject of universal surprise in Oswego county.

The prosecution was unhappy with the outcome and again brought Greenfield to trial on February 7, 1876, in Oswego. 333 persons were brought forth in search of a jury, from which 176 were drawn before the numbers dwindled to 12. By this point, the murder and subsequent cases were widely known, and finding twelve jurors was difficult. According to the New York Herald, the testimony was “substantially” the same as the first trial.

Shortly after the start of the trial, the Jamestown Journal reported on February 18th that Mrs. Betsey Ann Greenfield, mother of Orlando Greenfield, was arrested at her home in Orwell the previous week and placed in the Pulaski jail for having, along with her son Orlando, murdered her daughter-in-law Alice Greenfield. It was not found how long she remained in jail, but she testified (a point of which is made later.)

The trial ended up being delayed until May, and sometime after, the defense brought forth new evidence that was deemed questionable by some. On May 11th, 1877, Undersheriff Doyle received an anonymous letter with a postmark from Grand Rapids, Michigan, on May 9. The letter claimed to be from Alice Greenfield’s killer, who “killed Alice after satisfying his lust upon her, and declaring that Orlando was innocent of the crime,” according to a Watertown Daily Times article from October 26, 1877.

It was then stated that less than a week later, Judge Huntington obtained from Mrs. Hopkins another letter she received from Mrs. Alden Kellogg, written by Royal Kellogg to Alden Kellogg, dated Lafayette, Aug. 21, 1876. The postscript read, “Tell me about the murder if you think it all right tel them I am in Lafayetti (sic) and if they Want me they can come and get me.”

The two letters were described as “of the most illiterate description” and compared by numerous experts who determined they were of the same handwriting as Royal Kellogg’s. The District Attorney believed both letters to be forgeries to influence the case. Still, the defense contested the Kelloggs were arrested “on the ground of their presence at the Greenfield house on the night of the murder, the disappearance of Royal, these letters, and the finding of the gun in the possession of them or some of their friends.”

The jury consulted and, after 2.5 hours, concluded that Orlando Greenfield was guilty of the murder in the first degree–

The sentence of the Court is that you be taken hence to Oswego County jail, where you be securely confined until Friday, the 11th of May next, and that upon that day, between the hours of 10 a.m. and 4 p.m., either in the jail or in the yard adjacent thereto, you be hung by the neck, until you are dead, and may God have mercy on your soul!

A stay of execution was ordered, and the defense was granted time to prepare a bill of exception. The case was argued in Pulaski and then went to Rochester. Another stay of execution was granted, and the case was carried to the Court of Appeals, which reversed the lower court’s decision and granted a new trial.

It is believed this exception had to do with the perceived bias as the Watertown Daily Times printed—

With the amount of press the case had received and delays in the trial, Judge Huntington had heard comments “from time to time upon the case” which produced a bias and prejudice in the public mind while held in Oswego. It was motioned to have the trial moved to another county, many presuming it would be Jefferson with Watertown being nearer to the homes of the witnesses.

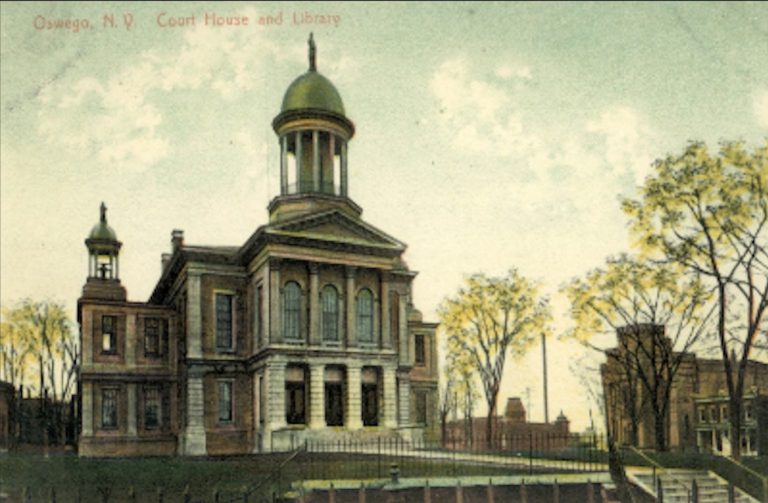

The Supreme Court ultimately designated the new trial to take place in Syracuse. After more delays with remitter-filing, it was held in the Onondaga Court House, and 100 jurors were drawn. The names were withheld for fear that publicizing them would lessen the chance of obtaining a jury.

After years of living in New Jersey, Alice Greenfield’s father, Albert D. Bloodgood, returned to Oswego during the trial and visited with an old employer, General T. Sullivan. After talking about the times gone by and catching up on current events, Sullivan asked Mr. Bloodgood if he had come to attend the Greenfield trial. Mr. Bloodgood replied he knew nothing of it and was greatly surprised to hear what transpired with his daughter over 3.5 years ago.

When the new trial began, Orlando Greenfield’s testimony changed from previous ones. This time, he claimed that just before the murder was discovered, he saw a neighbor, George Hinds, enter there and believed he had committed the murder. According to the New York Herald, the prosecution had shown the murderer had placed a hand on the door while it was covered in the victim’s blood, leaving an imprint of four fingers and a thumb from the right hand. However, Hinds was shown to have no thumb on that hand, discrediting Greenfield’s story.

On October 18th, 1879, Orlando Greenfield was found guilty, yet again, and sentenced to be hung on December 12. Another stay was granted until January 30th, during which time a rather curious article was printed in the Watertown Daily Times on December 13th with supernatural overtones—

Governor Robinsons’ Assurance

The Buffalo Express says: A day or two ago, at Richland Station, Oswego county, Mrs. Markee, a dealer of sorceries and familiar with all the ghosts on the calendar, told a Watertown reporter that “she had often talked with Alice Greenfield and she always said Orlando killed her.” In the teeth of this direct testimony, from the murdered person herself, Governor Robinson yesterday had the assurance to reprieve this wicked Orlando, whom Judge Daniels had sentenced to be hanged on Friday. What can Governor Robinson Mean? Does he know better than Alice herself who killed her?

Newly elected Governor Alonzo B. Cornell granted another stay until February 27th, at which point the Daily Times remarked, “Certainly this is the most celebrated case on record, and one that we hope will end soon.”

That date would come August 5, 1881, when Orlando Greenfield was finally hanged before hundreds of witnesses. At 10:48 a.m., he stopped on the gallows. 10:55, the chaplain finished his prayer, and Undersheriff Bennet tied Greenfield’s legs. Asked if he had anything else to say, Greenfield, who maintained hope until the final hour and continually professed his innocence, cooly replied, “No.”

The Buffalo News detailed what happened next—

The drop fell at 10:58. The body rose 15.5 inches from the floor. A minute later the legs and arms twitched violently, followed by continued trembling of the whole body. The neck was not broken. Greenfield hung 13 minutes and was then declared dead.

An interesting footnote: on the findagrave.com pages for both Alice and Orlando Greenfield, it is said that Charles Grinnell later admitted to the murder, but no information could be found to corroborate this.

As for Judge Huntington, this piece of information regarding the Alice Greenfield murder trial was found on newhorizonsgenealogicalservices.com—

Judge Huntington’s belief in Greenfield’s innocence became to him a certainty, when, as stated by Judge Churchill, at the meeting of the Oswego County Bar in April, 1894; Greenfield before the third trial refused to plead guilty to murder in the second degree, because by so doing he would admit that he killed his wife. And the feeling that a great wrong had been done contributed as much to Judge Huntington’s sorrow at the final execution of the sentence as did the failure of the labor of years.

One of the results of Judge Huntington’s labors in that case was Chapter 182 of the Laws of 1876, which provided that persons jointly indicted for crime could testify for each other, thus making Greenfield’s mother a competent witness for him.

The Ghost of Alice Greenfield

The following on the “haunted house” where the Alice Greenfield murder occurred was printed in the Watertown Daily Times on Dec. 23, 1879. It was initially printed in the Syracuse Standard.

Smith is the occupant. The story of the first appearance of the apparition is told as follows: Last week Thursday Smith’s wife made half a dozen mince pies. They were nice—crust short and crispy, and the interior raisined and spiced to the degree of excellence, that Smith remarked as he came home to supper, that he could “eat the hull of ‘em at one meal.”

He ate but three.

That night Smith awoke about twelve o’clock from a deep dream of peace. The light of the moon, shining feebly through the window, disclosed to his vision the ghostly outline of a female form looking into his bedroom door. He knew it was the murdered woman, Mrs. Greenfield, from the torn night dress and the red mark around her throat.

Smith’s hair stood on end as the ghost slowly raised its arm. It took one step into the room, with a cry of horror, he jumped out of bed and tried to escape. He couldn’t do it.

The ghost grappled with him and threw him to the floor and buffeted him and boxed his ears. After about half an hour’s hard fight, Smith swooned, when he came to he found himself in bed.

A mustard plaster of twenty horse power lay on his stomach, while two of ten horse power made it hot for his feet. On the stand was a cup of of catnip tea, while over him stood Mrs. Smith with a red stocking around her sore throat. Mrs. S. remarked:

“Smith, if I thought you’d ever eat three mince pies again, just before going to bed, I’d never make another mince pie in my life!”

Nine persons went up from Syracuse last Monday or Tuesday to visit the haunted mansion.