Huckleberry Charlie: The Sage Of Pine Plains Was One of a Kind

Charles R. Sherman, better known as Huckleberry Charlie, was born February 15, 1843, in Great Bend, N.Y., near present-day Fort Drum, though some reports stated Watertown. It was said he was born poor and died poor, but the Sage of Pine Plains, as he was often referred to after the name of the “wastelands” that eventually became Pine Camp, Camp Drum, and now Fort Drum, but one might be surprised to know he came from one of the North Country’s most prominent families, both rich in fortune and history.

Born the son of Eli P. Sherman, a Wall Street commission merchant and nephew of John A. Sherman, a substantial land owner and president of the Agricultural Insurance Company who gifted Washington Hall to the Y.M.C.A, Huckleberry Charlie, who earned this particular name from his picking huckleberries on Pine Plains and traveling all over the tri-county area to sell them and sauerkraut, was raised by his maternal parents in Great Bend at a young age after the death of his parents.

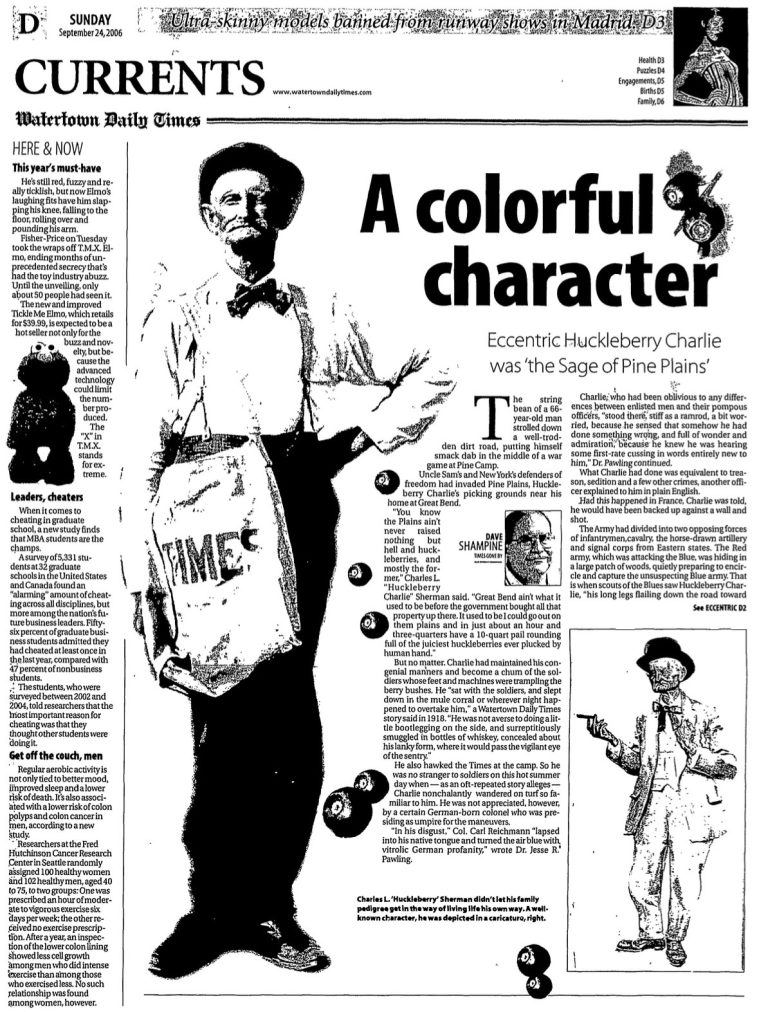

Very little was written about Huckleberry Charlie’s early life, but from the 1890s until his death in 1921, he appeared in more than 70 articles in the Watertown Daily Times, headlining many of them. He’s appeared posthumously over fifty times, with several features about him. So what made this unique and eccentric character so memorable?

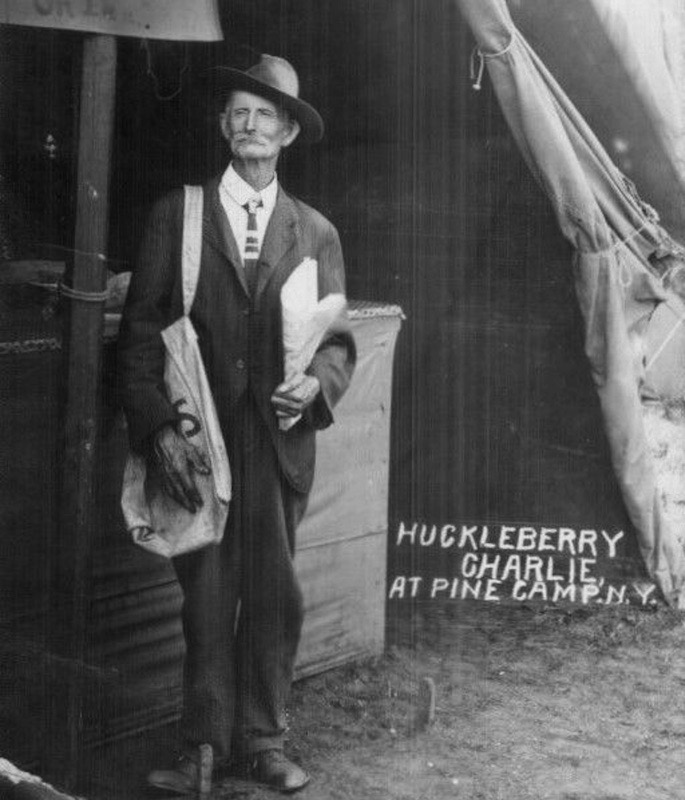

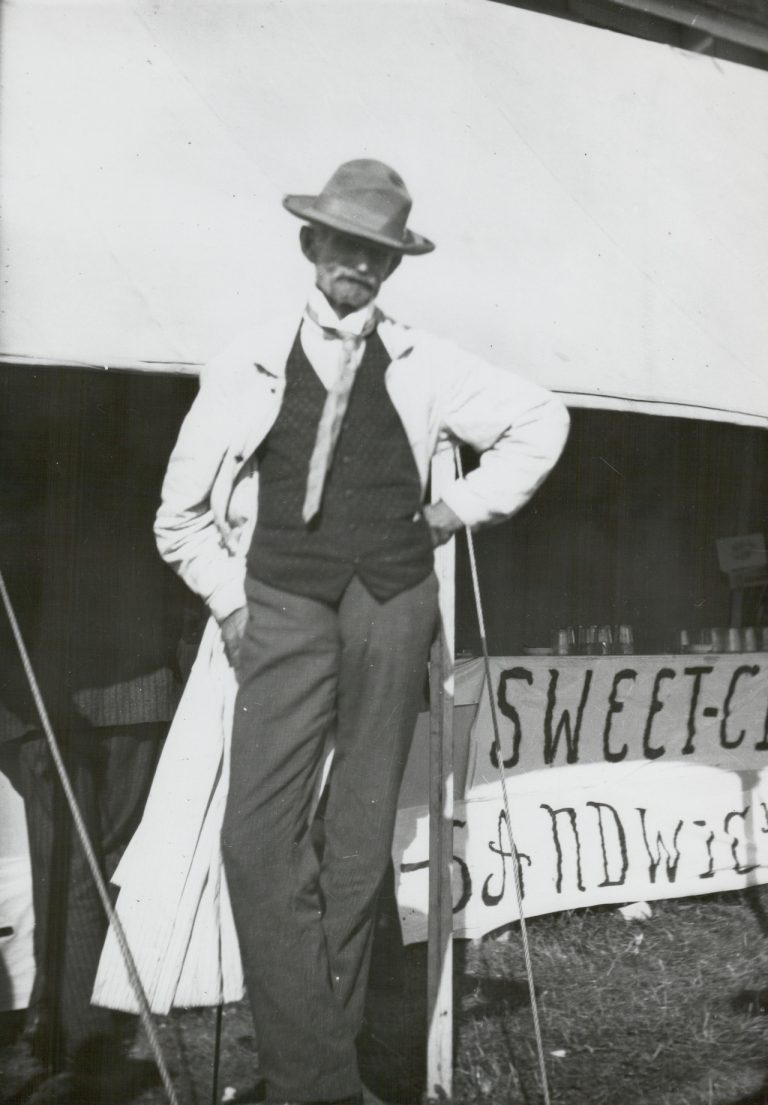

Huckleberry Charlie spent the summer months harvesting his trade when the huckleberries were ripe for picking on Pine Plain. During those months and into early fall, he traveled with his berries and sauerkraut, stopping in towns throughout St. Lawrence, Jefferson, and Lewis counties. Often wearing his trademark eye-popping apparel, typically consisting of flashy colors or contrasting patterns, and his oversized hats, he was a natural at selling himself, perhaps more than his goods. Wherever he went, he seemed to draw a crowd with his gift for gab, a necessity in the business of selling.

“These huckleberries were picked on the Pine Plains, are free from sticks, stones, stems and bruises. Some are black and some are blue. Come up and kind people and purchase a few. This is my last time through. Get your huckleberries,” he would say countless times a day. When asked how his selling was going, Huckleberry Charlie would often remark in code, “Come down to Watertown, sold all my huckleberries, went home with plenty of granulated sugar and made my cologne bottle smell 50 per cent sweeter,” granulated sugar being money and his cologne bottle could be interpreted as being his life was sweeter/enriched as a result.

When the huckleberry season was over, Charlie spent his fall months visiting all the various fairs. In the September 5, 1901, Watertown Daily Times article titled, “Children’s Day at the Fair,” The Times wrote–

Everyone is glad this year to see Huckleberry Charlie, who is as meager of a person and as sound of lung as ever, Charlie is dispensing peanuts and doing it with that lavish sang-froid which distinguishes all his actions, whether large or small. His stamping ground is the grand stand at the race track and between sales he strikes attitudes and tells the crowd about things in his inimitable way. He discourses of sauer kraut, huckleberries and mail routes and takes the bunch into confidence in the way that no one but Charlie himself has mastered.

On Tuesday he wore a red vest, but it scared the horses, so he obligingly took it off yesterday and appeared as a shirt waist man in suspenders. Charles is a wisp of a man, and to see him dodge through the human sandwich and carom gracefully off the edge of a crowd as it surges toward the fence, to reappear unscathed and with his basket untitled by an inch is a sight that is worth while to have come see. And he keeps right on selling peanuts as if he liked them. Those who know Huckleberry best are convinced that he could sell gold bricks, and are equally confident that he would never buy them.

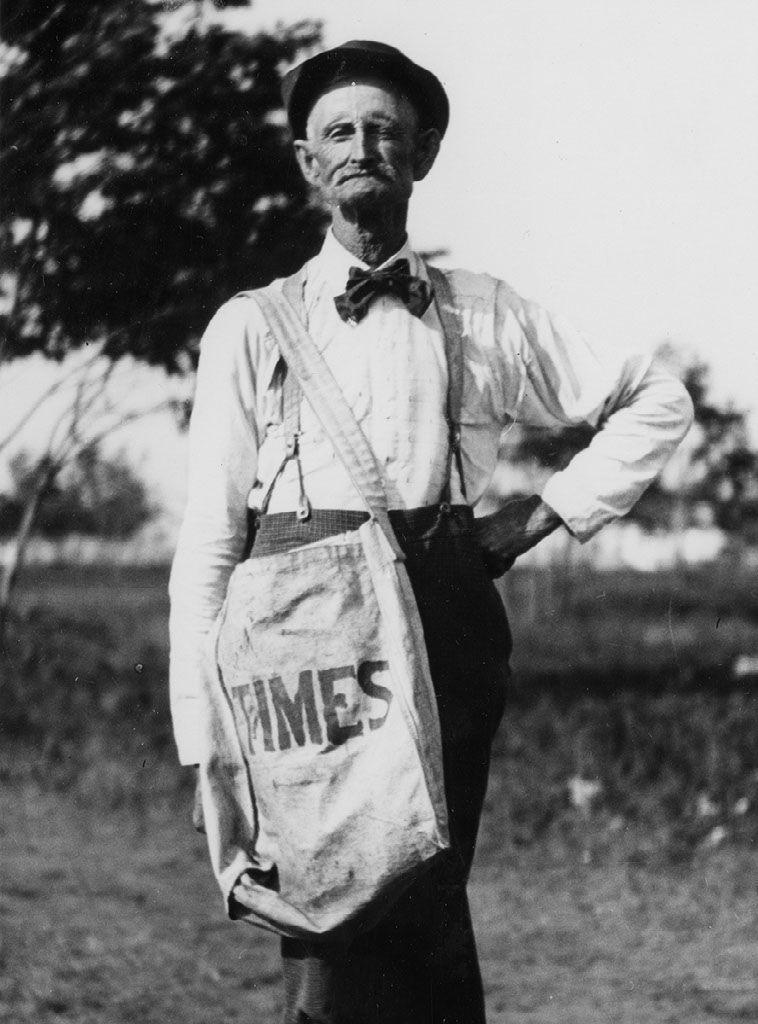

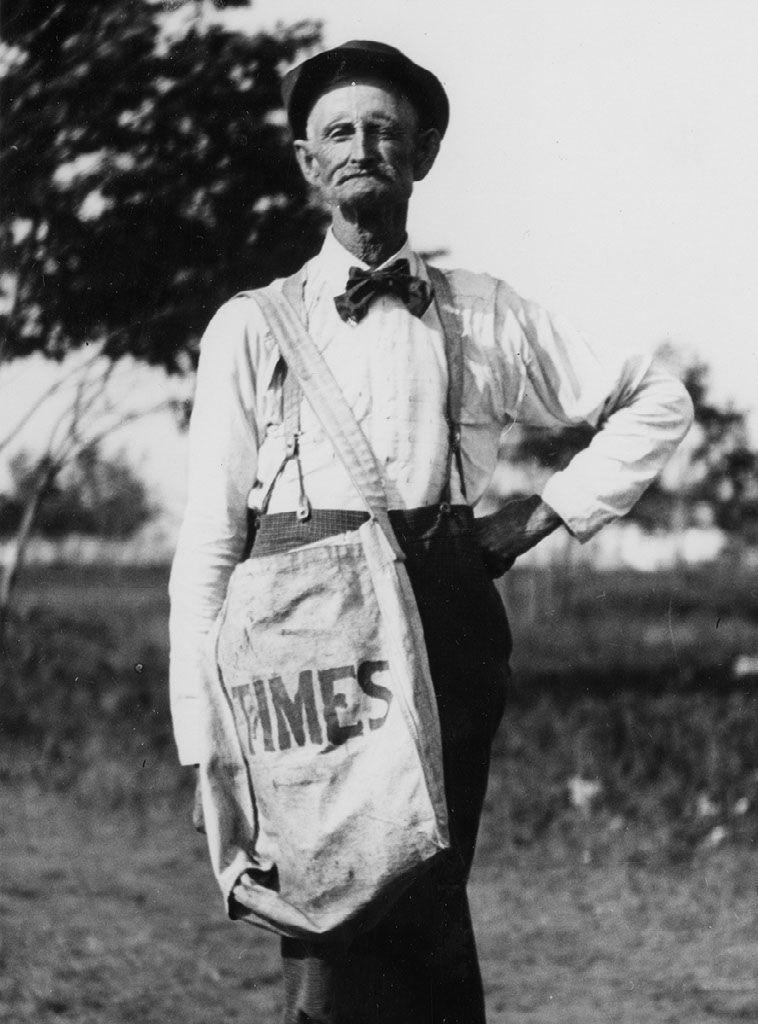

Peanuts, berries, and sauerkraut weren’t the only things Huckleberry Charlie sold. During the evenings, he once worked at one of the ten-cent theaters in Watertown, often delighting the audiences with a song and dance sketch that drew multiple encores. Charlie also made for one of the oldest newspaper boys for the Watertown Daily Times.

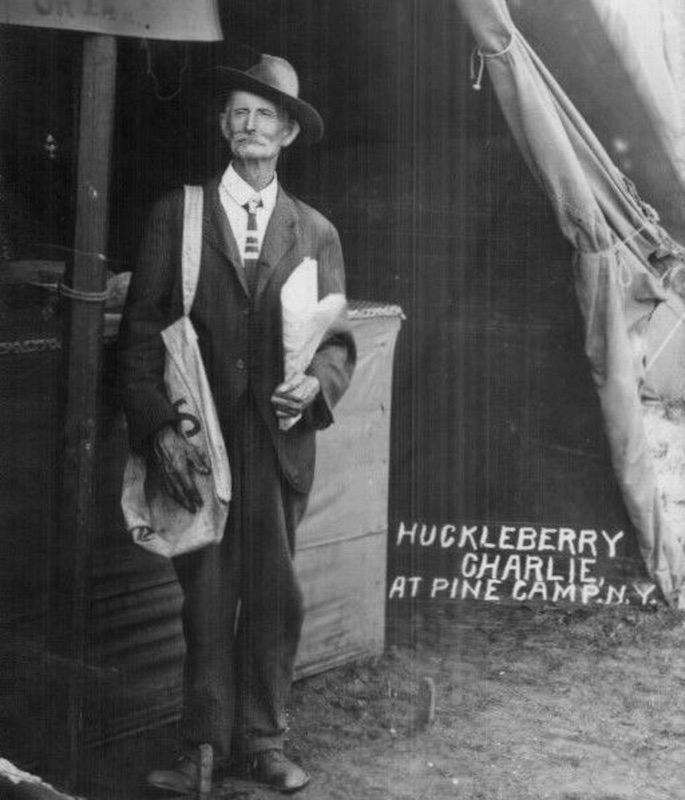

In 1908, while Pine Plains was being used for military training, it was opened to the public, and The Times reported that several thousand civilians thronged the soldiers’ camp. Charlie was amongst them, going from tent to tent, regardless of rank, and selling newspapers. “Do you want to buy the latest news? My name is Sherman, otherwise known as ‘Huckleberry Charlie.’ Pardon me, but don’t ye want to buy a paper?”

The Times wrote–

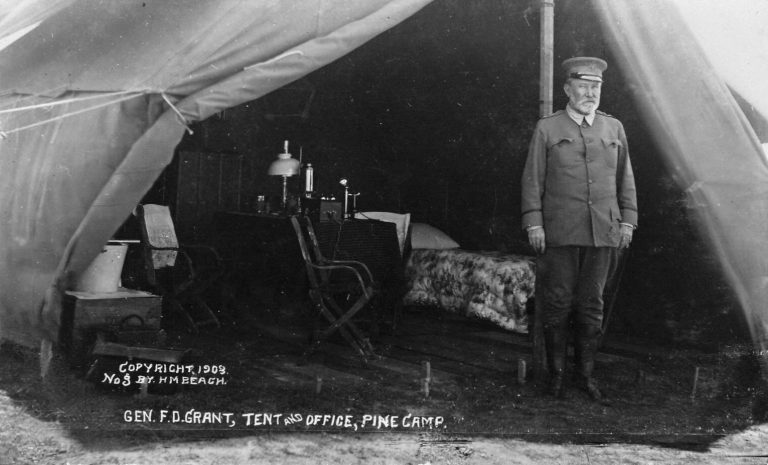

With this line of talk he visited nearly every tent and the same spiel was delivered at Gen. Grant’s tent as that of Private Andrew Jackson George Washington Brown of the 24th Infantry. “Charlie” is no respecter of persons. Some of the men tried to “guy” him, but Charlie was not to be “guyed.”

In one incident during the military maneuvers, Charlie ran afoul in a story best retold from the late Dave Shampine‘s column, Times Gone By, printed in the September 24, 2006 edition of the Watertown Daily Times–

The Army had divided into two opposing forces of infantrymen, cavalry, the horse-drawn artillery and signal corps from Eastern states. The Red army, which was attacking the Blue, was hiding in a large patch of woods, quietly preparing to encircle and capture the unsuspecting Blue army. That is when scouts of the Blues saw Huckleberry Charlie, “his long legs flailing down the road toward them,” Dr. Pawling wrote.

Charlie shouted a warning: “That piece of woods over yonder’s full of them fellers with red bands on their hats.”

The Blue Commander regrouped his forces and upset the skillful strategem of the Reds. Thus, with the unexpected help of one man, the war game went awry.

The colonel watching the maneuvers found out and wasn’t the least bit happy. Huckleberry Charlie, to his credit, offered a defense in what could have been in Forrest Gump (just end the sentence with to Lieutenant Dan): “As long as the fellows with the blue bands ‘round their hats see that I don’t go hungry, I wasn’t agoin’ to see ‘em all captured,” he said.

Late one fall, Huckleberry Charlie entered the Big Amateur Contest at the City Opera House in Watertown. Amongst a sea of contests that included entries for dancers, singers, boxing, acrobats, and a ladder act, Charlie was the lone comedian.

After disappearing for some time in 1909, Huckleberry Charlie reappeared in early 1910 with a new act, a traveling minstrel. He joined the Eagle’s Club minstrels and was looking forward to performing in Watertown on a Wednesday in Watertown. The afternoon show was said to have been well-attended, but the evening show, benefiting the Sister’s Hospital, was sold out–

One of the features not on the program, but which nevertheless called out perhaps a larger share of applause than any other number, was that of Charlie Sherman—Huckleberry Charlie. His act consisted of several songs, so-called, and an original monologue dealing with the Pine Plains and the country surrounding.

Charlie also entertained the local Elks Club a few years later when, upon arriving in Watertown, was persuaded to make a trip to Syracuse and entertain its members on the train. When threatened with arrest for not having a ticket on him, members gladly paid for his fare. Oftentimes, when coming to Watertown, Huckleberry Charlie would tell the merchants he visited that it was his birthday. In turn, they would give him all their unwanted and unsaleable goods.

Then there is the interesting fact that Charlie grew up and was boyhood friends with Frank W. Woolworth. In 1915, when Woolworth, worth millions by this time, was visiting Great Bend for the dedication of the Methodist Episcopal Church, which he had donated to the people of the village, Huckleberry hit him up for the 50 cents he claimed he loaned him years ago. Woolworth obliged, reportedly stating, “It seems good to see a familiar face, even if it did cost me half a dollar.”

In a retrospective piece on the Sage of Pine Plains, it was said that Charlie often talked of his “Aunt Lucy” and how he hoped to inherit a fortune from her in his old age. “When Aunt Lucy slips her wind I expect to slip from Great Bend forever, Great Bend’s no more a place to raise a crop than hell is for a powder house,” he would say. Another popular quote from the Sage was, “Wished I lived where it was six months night six months day. Like to get there about sundown where you could get a good night’s sleep. Be hell to get there sunup, wouldn’t it? Be a long time afore dinner.”

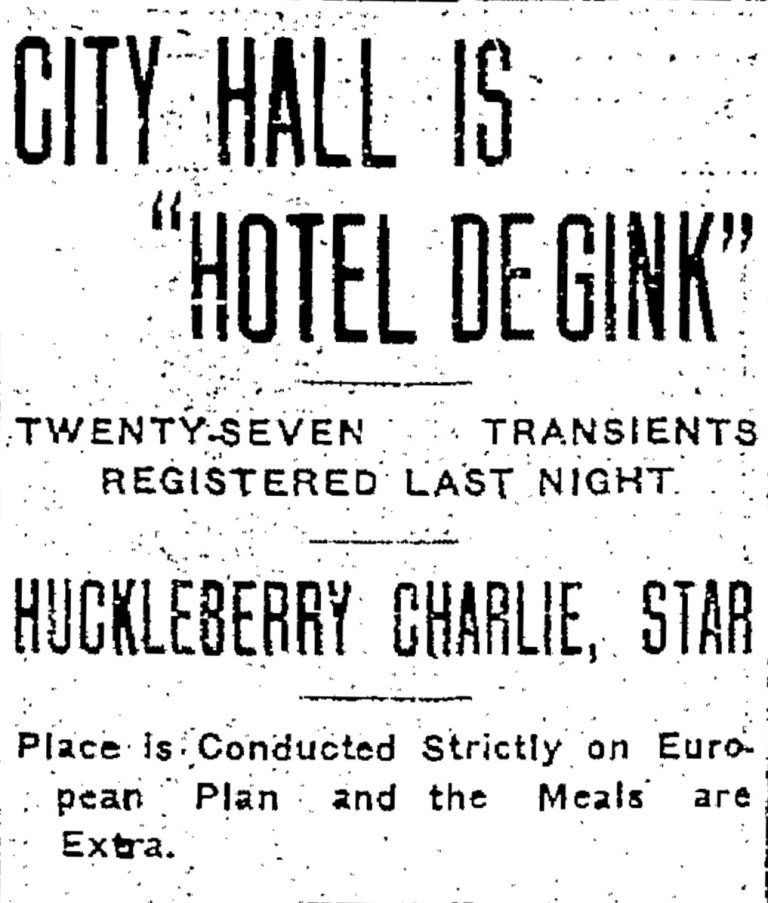

In April of 1916, The Times reported that City Hall resembled “Hotel de Gink,” as 27 transients registered for a “night’s lodging,” and Huckleberry Charlie was the star boarder. According to the article–

Charlie applied for a room about midnight after having had a hard night with the boys. With a bright red necktie that shone and glimmered under the lights, and an artificial bouquet on his coat he looked the man about town. He may be able to navigate the sandy wastes of Pine Plains all night, but he zig-zagged down Court Street like a munition ship trying to dodge a U-boat.

Charlie immediately registered, left a call for 7:30, ordered his “bawth,” and retired to the patrolmen’s room, where in a few minutes he was dreaming, not quietly, of calvary screens, reconnaissances, night attacks, and rear guard actions, memories of his strenuous days on the plains.

As the years went on, Charlie continued just as usual but slowed within the last year of his life. On November 19, 1920, it was reported that he was seriously ill and that his recovery was doubtful. His illness was due to a “general breaking down, complicated with cancer,” as he was confined to his house under the care of his wife and daughter for the last six weeks. While he spent the summer picking berries as usual, he skipped traveling to all the fairs because of his illness.

Charles R. Sherman, better known as Huckleberry Charlie, passed away at his home on Market Street on January 13, 1921, at the age of 77. Fortunately, through The Times, his legend lives on.

1 Reviews on “The Legend of Huckleberry Charlie (1843 – 1921)”

It is in the enchanting persona wherein lies a secret key. It is this sparkling key that opens the aged door that time has shut. Venture through. Huckleberry Charlie is waiting for you.