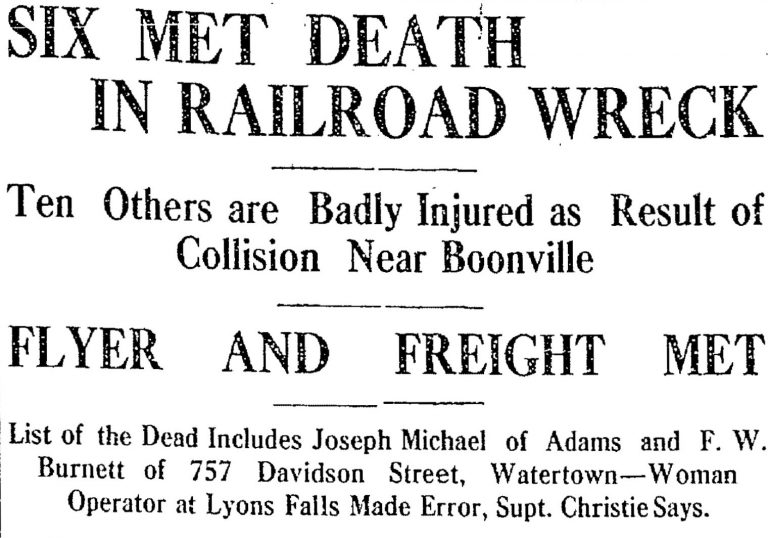

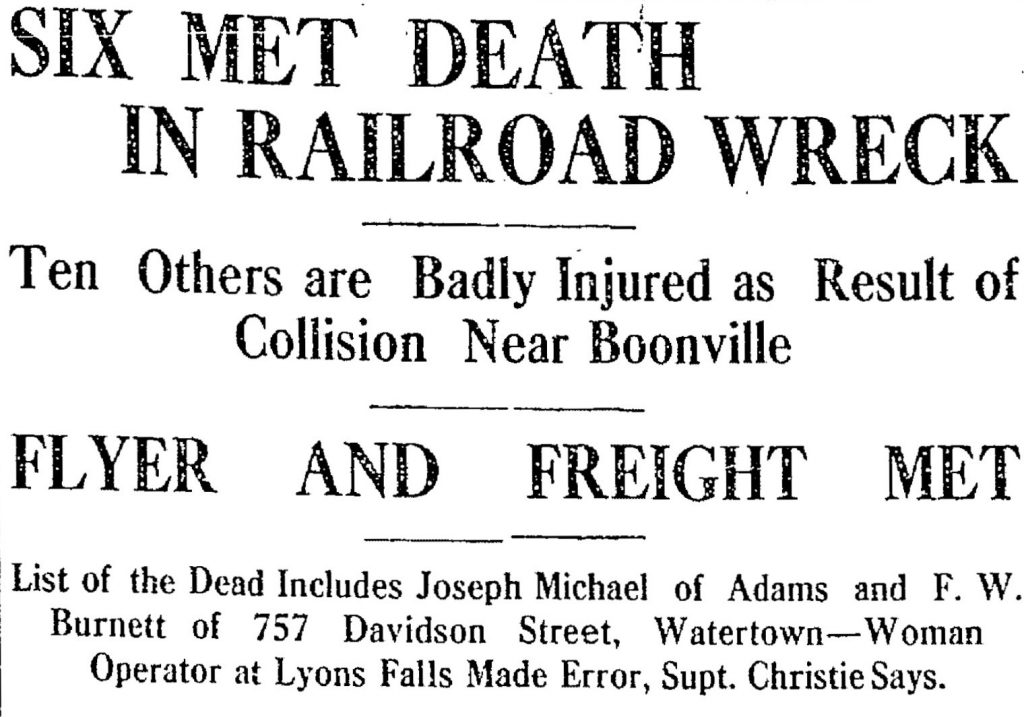

Boonville Train Crash One Of Worst In History Of Rome, Watertown & Ogdensburg Division Of NYCRR.

Called one of the worst train accidents in the history of the Rome, Watertown & Ogdensburg division, the Boonville train crash on July 4, 1908, involved two passenger trains and one freight train in a head-on collision that took the lives of six people. Among the prominent passengers of the trains were well-known 1000 Islands residents George C. Boldt of the Waldorf Astoria and Heart Island; Thomas Wheeler of New York and Wau Winet; Alex Robb of New York; James Norris Oliphant of New York and Neh-Mahbin; and Charles R. Skinner, former U.S. Congressman.

The accident occurred approximately 1.5 miles north of Boonville at 5:32 on a Saturday morning with one of the passenger trains heading to the Thousand Islands.

The Watertown Daily Times detailed the Boonville train crash in its July 6th edition, stating, in part—

Four lives snuffed out in the twinkling of an eye, two terminated at the end of hours of torture, 10 other persons maimed and mangled, some of whom are so seriously hurt that death may result: three locomotives, one combination, one baggage and four freight cars twisted and torn and fit only for the scrap heap; thousands of dollars’ worth of personal baggage ruined—this, in brief, is the result of a head-on collision between a north-bound passenger train and a south-bound freight one and one-half miles north of Boonville at 5:32 Saturday morning, one of the worst wrecks in the history of the Rome, Watertown & Ogdensburg division.

The wreck was determined to be caused by a train order written by a New York Central telegraph operator, Mrs. E. R. McLane, at Lyons Falls, which erroneously listed “fifty-five” for “fifteen” in re-writing the order. Mrs. McLane, a former resident of Factory Street in Watertown, had only been working for the New York Central since July 1.

According to the investigation, the fatalities were nowhere near as bad as they may have been had the passenger trains not been going more than 20 or 25 miles per hour and the freight strain more than 10.

The deceased included F. W. Burnett of 757 Davidson Street, Watertown, a fireman on one of the two passenger trains who later died of injuries at St. Luke’s Hospital in Utica; John O’Brien of Glenfield who also died at St. Luke’s; Albert Rieber, Washington Street, Utica; Stephen G. O’Brien, Seymour Ave, Utica; Andrew W. Hagemen, Sunset Ave., Utica; and Joseph Michael Adams.

According to the Watertown Daily Times article dated July 6th—

The men in charge of the freight train bound for Utica supposed, after receiving an order at Lyons Falls, that a northbound passenger train would be waiting on the siding of Boonville at 5:55. The order should have read “5:15,” say the railroad people. And as a result of the misunderstanding the trains met on a single track and the terrible accident followed.

There were about 20 or 25 cars in the freight train that figured in the accident. These were filled with various shipments from the northern country, much of it being dairy produce, groceries and general merchandise. One of the first cars on the train was loaded with cheese.

The three engines involved in the fatal wreck were No. 1969, No. 1723, and No. 2414. The impact could be heard from a mile away as No. 1969, pushed forward by No. 2414, with which it was “coupled at head of nine coaches,” smashed into engine No. 1723. The Times stated, “Like monsters, they tore into each other in their contest for the right of way.”

The trains careened toward the canal, toppling over. The ensuing pile-up, with various cars thrown side to side and striking each other, filled the air until all was silent for a short moment. Then, the injured crawled from the wreckage, dazed and confused, to assess what had happened and help fellow passengers.

The Times report on the Boonville train crash continued with the following—

The wrecking crew from Utica, under Mr. Griffin, was summoned as soon as possible and the train was started shortly after 7. The wrecking crew from Watertown was also put at work on the big task of clearing track and help was also secured from Syracuse. A big party of laborers was kept buys laying a new track as soon as the twisted rails were taken out of the way and this work advanced by rail lengths with the clearing of the debris from the road bed proper.

A farmer, Michael Wall, who lived a short distance from the Boonville train crash saw the freight coming from the north and, knowing the Thousand Island special from Utica was due, tried to flag the freight train with his hat to no avail.

Eyewitness Frank Zimmer was the first person to witness the collision, stating—

“I had just come from the barn with a pail of milk when, looking down the track I saw the two trains smashing into each other. I ran down and saw the engineer from one of the two engines that drew the passenger train from Utica, land by the fence. I raised his head he said, ‘What’s happened?” I told him, and he dropped right back.

Then I got up to the smoker, smashed one of the windows and then saw that a lot of people needed help as soon as they could get it. I ran up to my barn and hitched up my best horse and drove down to Boonville to get some doctors. I brought Dr. Douglass back, after notifying the other doctors.”

Charles R. Skinner was aboard the passenger train going from New York City to Watertown and recounted his story to The Times—

“The train for the north left New York in four sections. Section 4 was the Clayton section, composed of six sleepers, one day coach, one combination baggage and smoking car and an extra baggage car.

“The train was late in starting. It was due to leave at 7:15. It lost much time, so instead of reaching Utica at 1:55 it was 3:50 before we left. From Utica we had two locomotives. One the first was Engineer “Al” Keiber of Utica and Bert Lingenfelter of LaFargeville. One the second was Engineer Stephen O’Brien of Utica and F. W. Burnett of Watertown.

“We made good time to Boonville. A stop was made here and the caution signal was given, which allowed the train to proceed. About two miles north of Boonville we met a long freight train coming at full speed around a curve. The road here is along the line of the canal. The train was not going over 20 or 25 miles an hour otherwise the loss of life would have been greater.

Two other deaths, drownings, happened as an indirect result of the Boonville train crash when the Black River canal water was drawn to search for possible victims, causing an undertow that led to the deaths of two swimmers later that afternoon. The victims were Frank Stahl and his nephew Harry Stahl.

Initially accused of the accident due to miscommunication and admitting so, Mrs. E. R. McLane accused 19-year-old George Godreau, an operator at Boonville, of allowing the Thousand Island Special into the block without waiting for an order from her. She had less than three months of telegraph training prior to the start of the job and reported being uncomfortable doing it, though she proceeded because no one else was available. Ultimately, she was found to be at fault by the coroner who also censured the railroad company for not employing a higher grade of operator and exercising more care in their selection.

On a positive note, a dog in the smoking car rescued himself without injury (though badly shaken.) The Times noted farmhouses in the vicinity of the Boonville train crash were visited for breakfast, but they soon gave out, and despite the tragic deaths involved, the injured and other passengers alike remained calm with no signs of panic.