The 1897 Crouch-Daly Double Murder Outside Sackets Harbor Remains One Of The Area’s Most Disturbing And Mysterious Tragedies

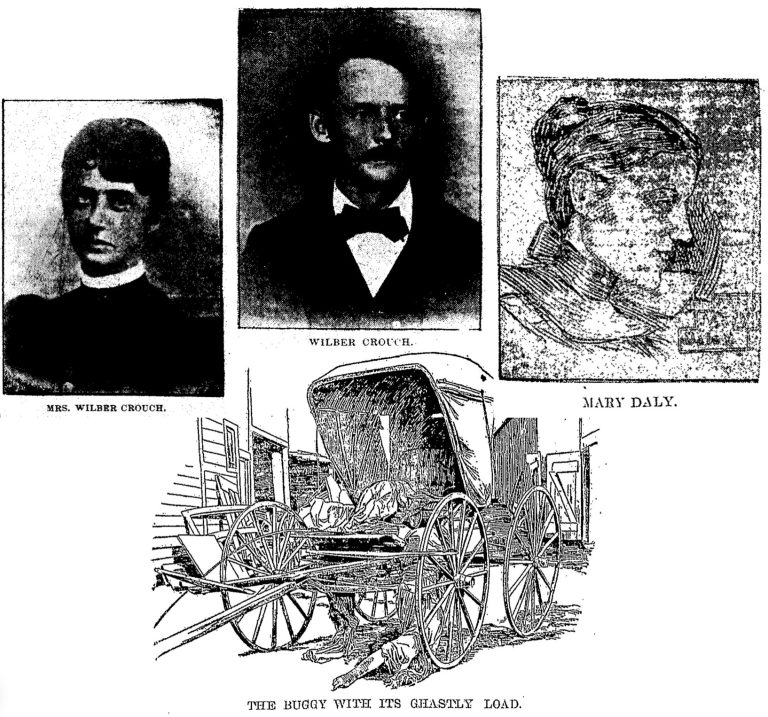

In the early morning hours, just past midnight, of April 16, 1897, what would become known as the Crouch-Daly Double Murder occurred, leaving two dead and one-near death and arguably a fourth victim. The ensuing mystery that followed was perhaps the most discussed event of its time as theories and facts blurred in what would become the longest trial in New York State history and the most costly one in Northern New York.

The trial also helped pave the way for modern forensic science though the outcome was based entirely on circumstantial evidence. In fact, to this day, nobody knows exactly what happened or why other than the perpetrator.

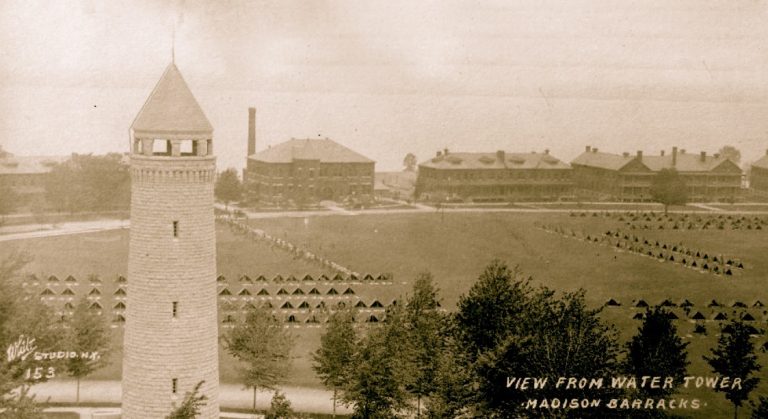

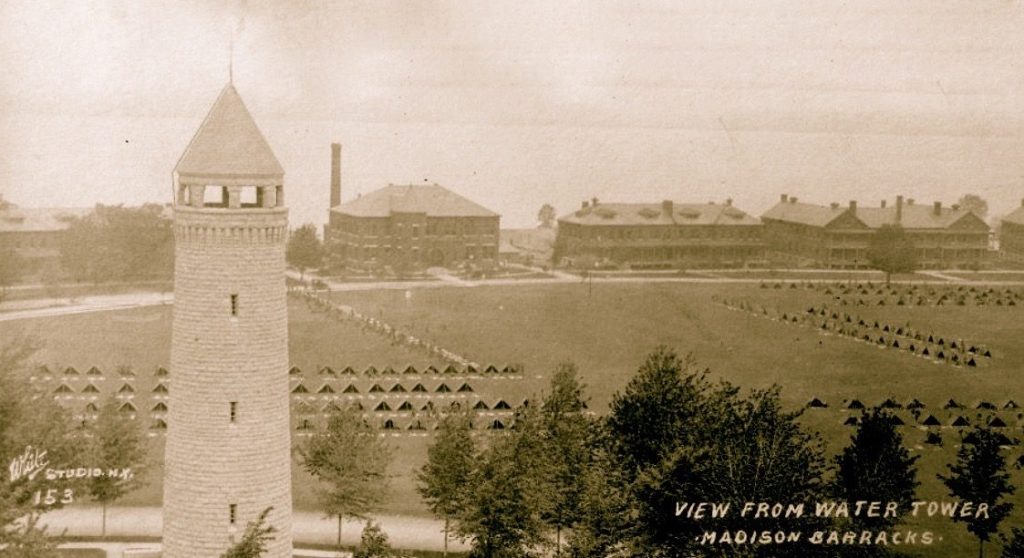

The events, dubbed by the Watertown Daily Times as “the strangest and most shocking tragedy ever recorded in Jefferson County,” unfolded in what sounded like the opening of a horror movie. The primary characters were two women, a private stationed at Madison Barracks, and a jealous husband. Two of the victims arrived in Sackets Harbor around the same time the third, having been separated from the others, made his way to the hospital at the barracks.

(To note: “Team” references the horses, as in a team of horses.) What follows is the events as printed in the Watertown Daily Times, which pulled no punches in some of the haunting descriptions–

THE FIRST SIGN–Appearance of the Team Drawing the Carriage and Two Corpses

At about 2:45 this morning, as Willam Markham, who is employed by Liveryman Thomas Jackson, was unhitching a horse that had just been driving into the stable by two soldiers who had returned from Watertown another team belonging to Mr. Jackson came running in without a restraining or guidance hand on the rein.

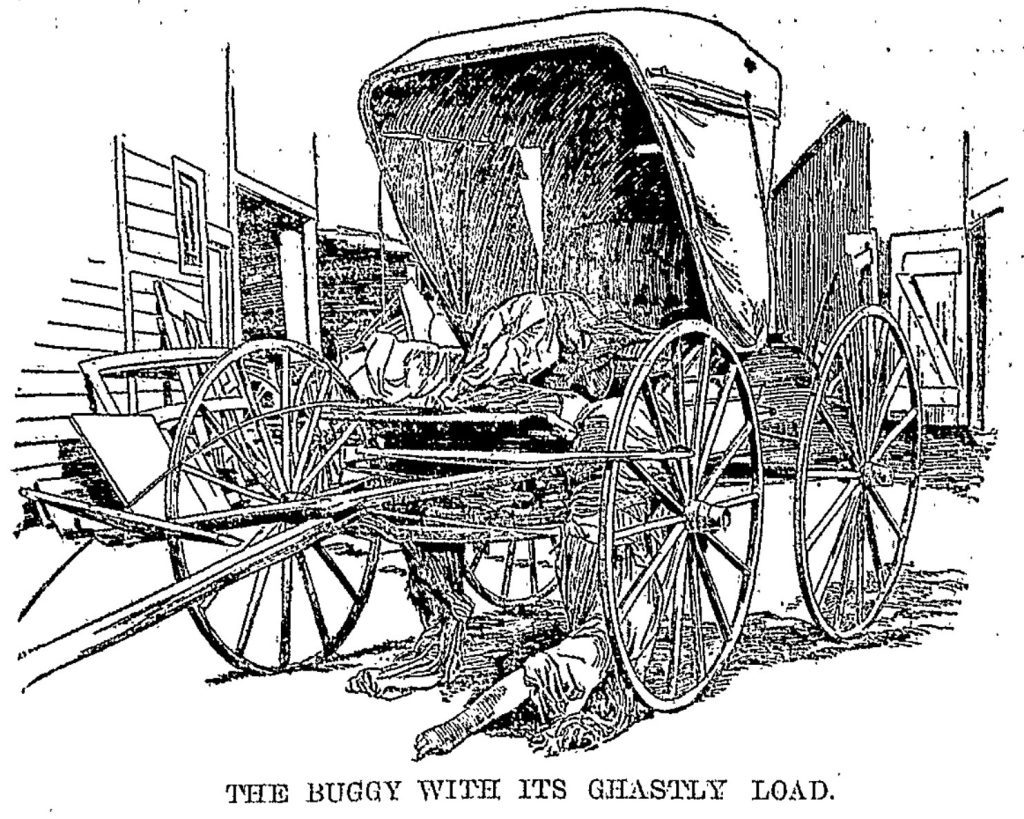

The horses stopped and Markham stepped to the buggy to see what the strange load was that it carried, partly in the box and partly hanging and dragging on the outside. His blood chilled as he saw that the carriage was occupied by the corpses of two women.

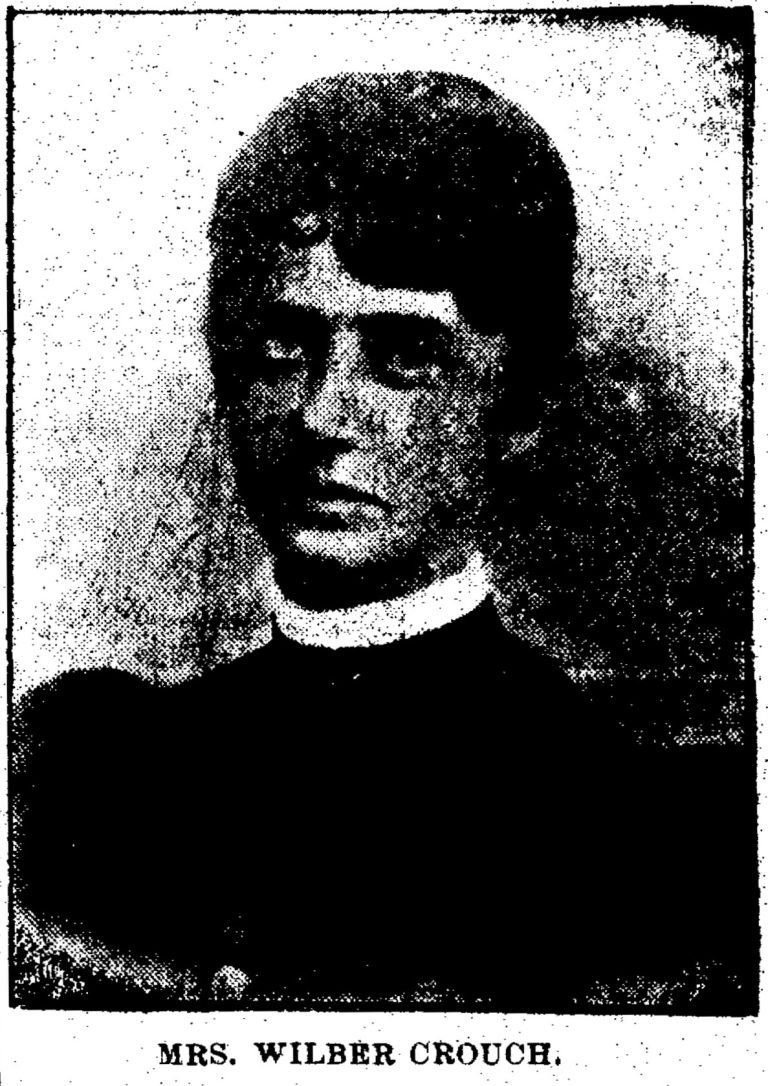

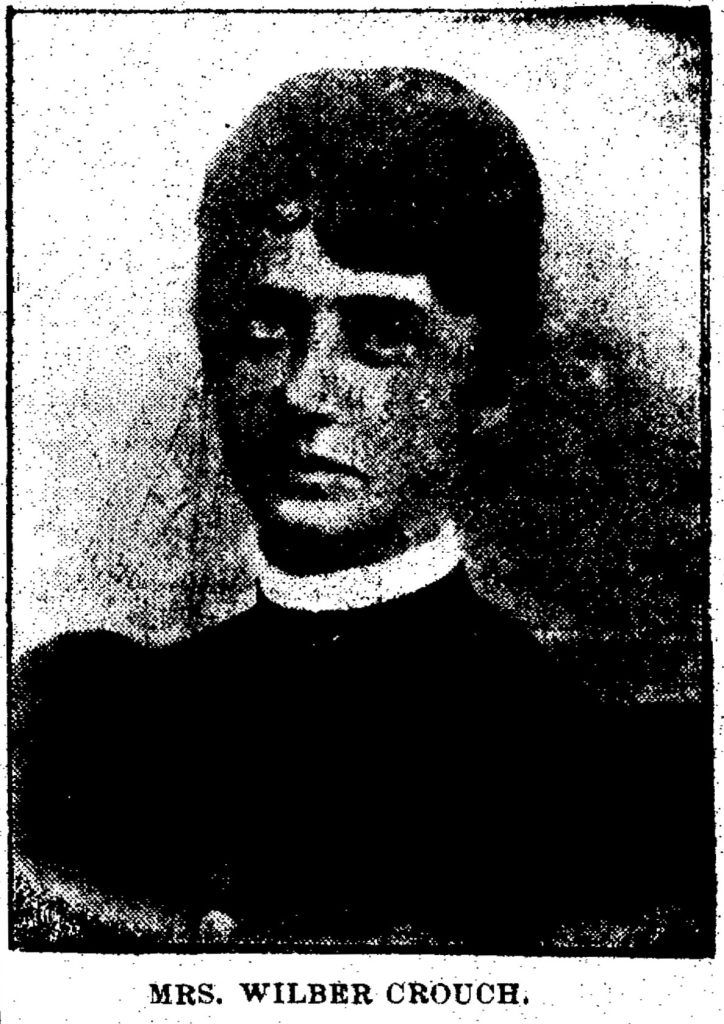

One was the body of Mrs. (Mary Shannon Crouch) Wilbur Crouch. It was on the left side of the buggy, most of her body being outside of the box and her head on the floor of the barn, the body between the forward wheel and the dash. Her disheveled hair had trailed through the mud and her face was covered thickly with mud as if it had passed through a puddle of the roadway.

Blood was oozing from a large wound in the head. The scalp had been peeled partly from one side of the head as if by violent contact with a stone. The other woman was Mary Daly. She had sunk down into the bottom of the buggy box. Her clothes were badly burned, especially on the back, and the fire had eaten away a part of the fabric of her corset and exposed her undershirt.

One of Mrs. Crouch’s feet had been caught under the seat and that was what held her body in the position in which it had evidently been during a ride of several miles.The paint had been worn from the buggy wheel where it had come in contact with the body.

During the inquisition, it was said that Mrs. Crouch, 33, was still alive at the time of the arrival and heard moaning. Isaac P. Ware, assistant surgeon, United States Army, confirmed she was still alive when she was found but died shortly thereafter. He attributed death to both gunshot wounds, of which she had three, and partly due to the bumping of her head.

Dr. Paul Shillock performed the post-mortem on Mary Daly, approximately 30 years of age. He noted death was most likely instantaneous from a gunshot to the back of her neck resulting in a bullet lodged in her skull, fracturing it, while damaging blood vessels that caused hemorrhaging.

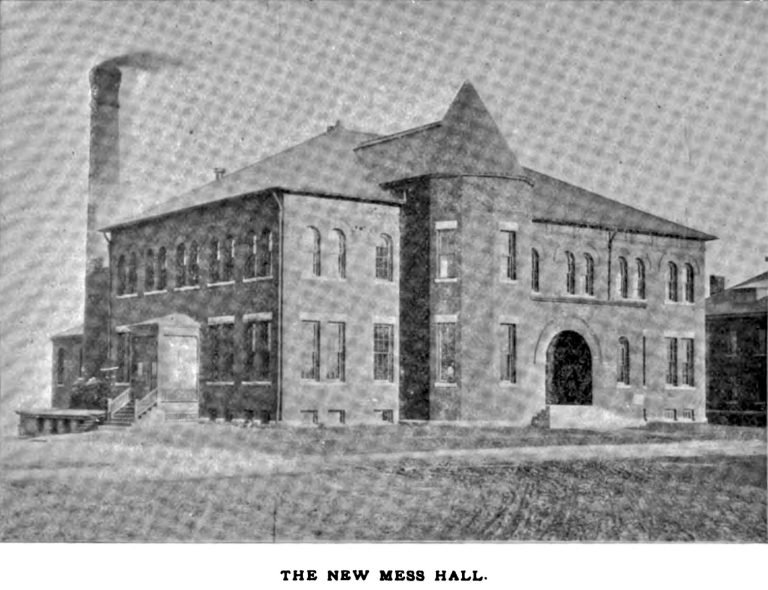

About the time of the charred, driverless buggy arrived at the stable, the third victim, Private George Allen, arrived at Madison Barracks clinging to life–

THE THIRD VICTIM: Allen Crawls To The Barracks And Tells The Terrible Story

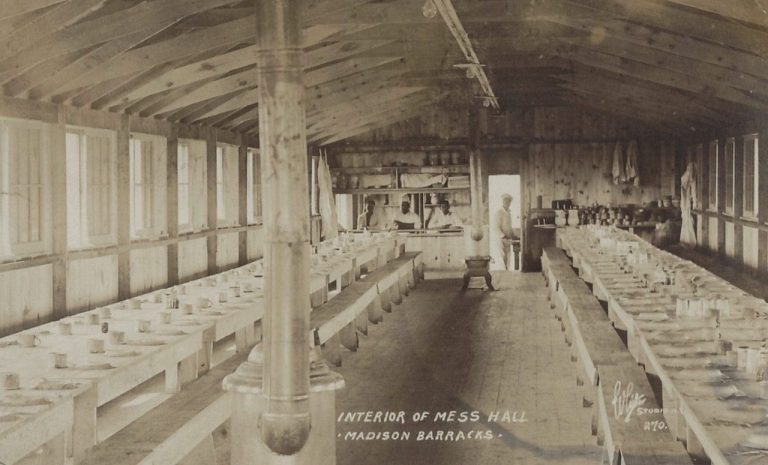

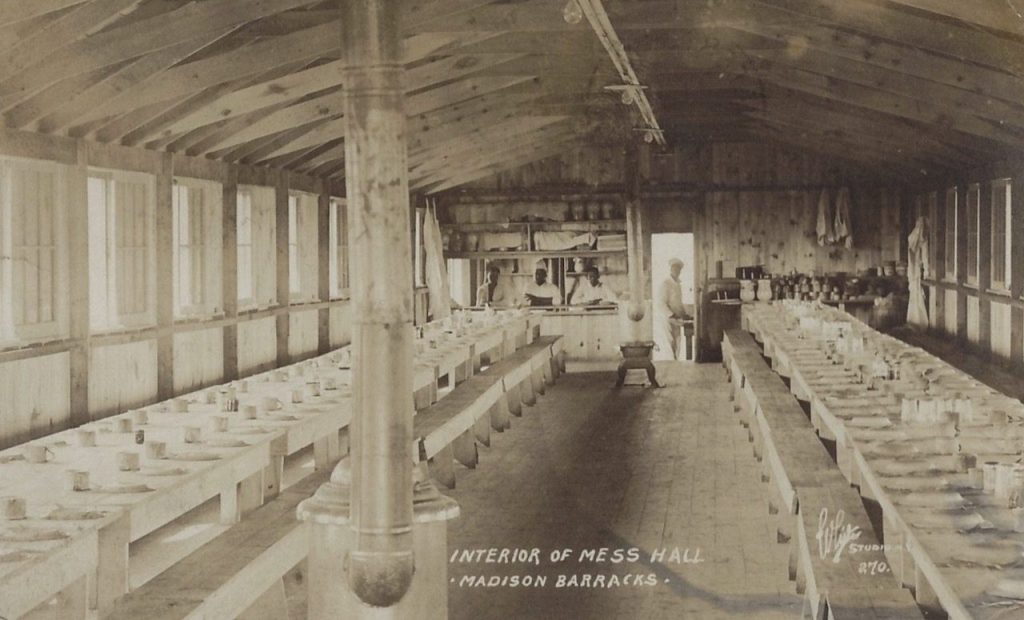

James (illegible) was preparing to bake the day’s batch of bread at the mess hall at Maddison Barracks at about 3:30 this morning when George F. Allen, private Company F, 9th Infantry, U.S.A., staggered and fell into the mess hall and asked for assistance, pleading to be taken to the hospital. Help was obtained and he was carried to the hospital near by. On the way and during the interim he gave incoherent utterance to the story briefly outlined in the introduction paragraphs of this report.

Allen was found to be suffering from severe shock and was very wet, as if he had been completely roused. He complained of being cold and was found to have three wounds on the right side of his neck, with two cuts in the forehead, as if he had been struck with a stone. There was one bullet wound over the right temple and a contusion on the left breast, while his head was covered with bruises.

Below is the first-person account/statement of the events by George Allen.

Last night, about 8, I went to Thomas Jackson’s livery stands and hired a team to take Mary Daly and Mrs. Crouch to the home of Mrs. Carr, Mrs. Crouch’s mother. A soldier named Davis rode to the barracks club with me, where we got some cigars. I told Davis that Crouch had seen me get the team and was watching me and would probably follow. I took the women in the carriage and we went to the home of Mrs. Crouch’s mother, I noticed a buggy on another road near by as we were returning.

We were about a quarter of a mile from Mrs. Carr’s when we met a man in the road afoot. The man grabbed a line and stopped the team. I recognized him as Crouch. Mrs. Crouch was sitting on the left, I was on the right and Miss Daly was sitting on my lap, driving, while I had my arm around her.

I tried to start the team, but Crouch hung on. I started to get out of the buggy. As I did so Crouch hit me with a stone which he held in is hand. I fell forward on the dashboard. I tried to make a bluff with a little 22 calibre revolver, that I had and by accident it went off and shot me.

Allen became somewhat indistinct at this point and could not say where the bullet hit him. Mrs. Crouch exclaimed “Oh, my God!” Then several shots were fired by the assailant. Miss Daly fell forward and then Mrs. Crouch fell, both on me, pinning me down in the buggy. It seemed to me that as many as sixteen shots were fired.

Crouch then got into the buggy and took reins and drove to the Watertown road and up that road to turn toward Brownville. I have an impression that there was a younger man with Crouch part of the time, but cannot say for sure. After he started with us up the Watertown road, I revived slightly and struggled out from under the women.

Crouch then hit me on the head with a stone or something sharp, and whenever I would move or show any signs of life he would pound me on the head and shoot me. After we had gone some distance the man pulled me from the buggy and threw me into a creek or pond. I floated ashore and crawled up the bank and across the fields to the hospital.

Allen then pleaded for those about him to go and get the women, saying that they were in the creek. The news of the arrival of the bodies of the women in the stable had reached the barracks by this time, and Allen was informed that the women were not in the creek and were all right. He seemed to be devotedly attached to Mary Daly and spoke of her constantly, making anxious inquiries of as to her safety.

The testament held up against facts derived from a search the following day, more articles were found on the route along with pools of blood. Also corroborating Allen’s story, his overcoat was found on the bank of Mill Creek, not far from where the marks were left behind of his crawling out of the creek were found.

The only thing that wasn’t corroborated was the revolver. Upon further investigation, it was determined that the gun was purchased by a boy, Frank Gomery, at the direction of Allen.

The revolver was reportedly found by a ten-year-old boy, Eddie Hicks, walking from his home on the Hicks farm to Sackets Harbor, about where Allen was dragged from the buggy and where his shoe was found. The gun was purchased the day prior from Stearns’ store and later identified by Mr. Stearns as the one purchased by the Gomery boy.

The Times noted, however, the potential for the misinformation–

It is assumed, however, that Allen was unable to recall all of the circumstances connected with the case when he was interviewed by the doctors this morning, and he may explain his possession of the revolver later.

It is known that he was afraid that Crouch would attack him and he undoubtedly prepared himself for such an emergency.

Allen’s record was good, and shown to be a man of good habits, having served (reportedly, but incorrectly) a dozen or more years of military service and thought to have been 32 to 35 years of age. In fact, Allen was serving a five-year stint. He had completed three years, allowing him to furlough, which he did, with plans to wed Mary Daly the following day before taking the option to retire from the military and return to civilian life.

At the time of his hospitalization, he was clinging to life, and doctors had differing opinions on whether he would survive. He was, in fact, 29 years of age, considered to have a strong build and handsome.

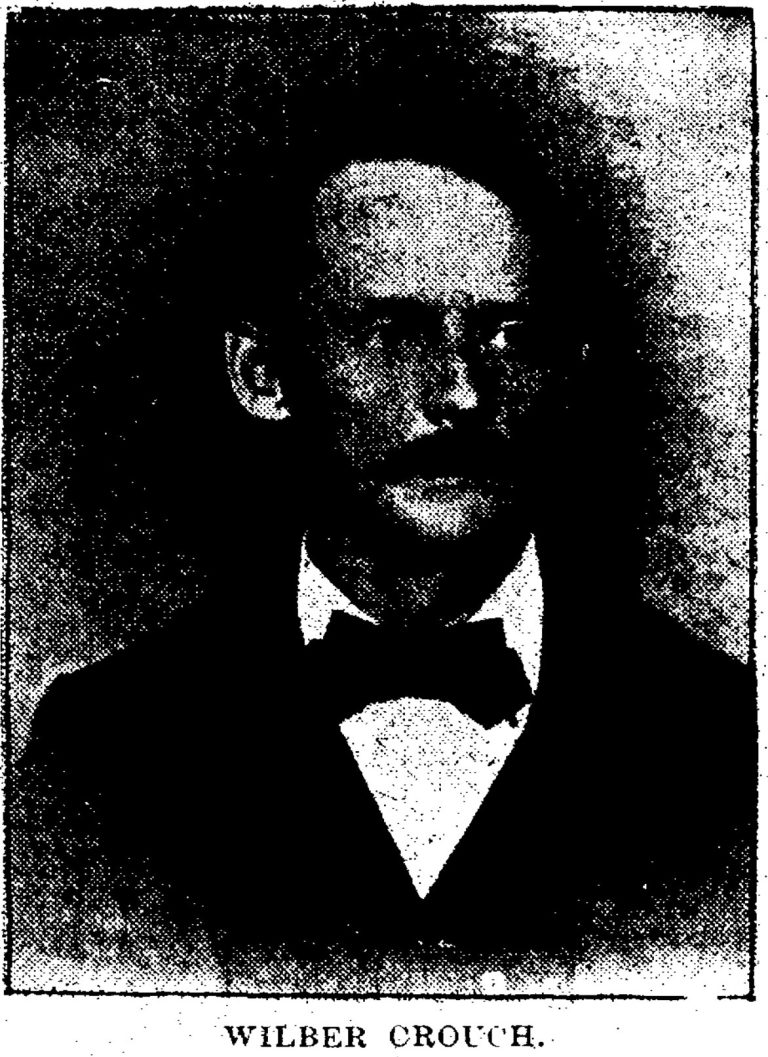

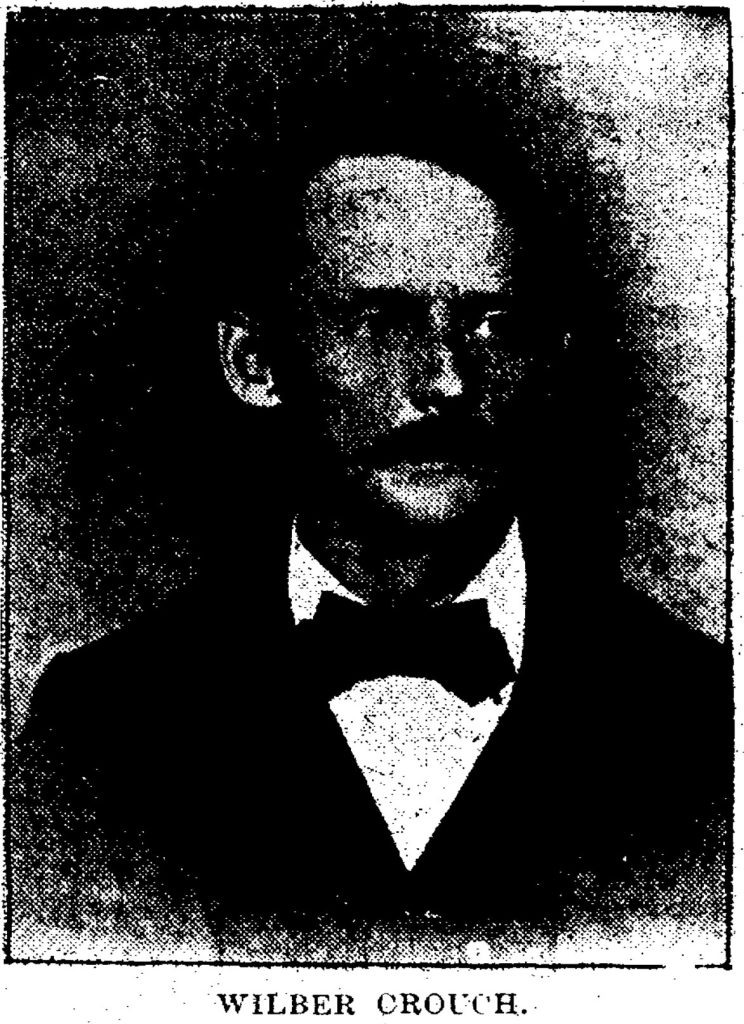

Wilbur Crouch’s reputation was never in question. The 44-year-old had a bad reputation, an alcohol addiction, and was the ugliest of drunkards, having beaten his wife numerous times, leading to her separating from him. He married Miss Mary C. Shannon on August 13, 1885, but separated seven years later in 1892.

In October of 1894, Mary filed for legal separation, citing, along with the beatings, that he threatened to blow her brains out, choked her, spat on her, called her vile and lewd names and forced her to clean the horse barn and harness. If she didn’t, he would kick her.

The judged allowed the children to be taken to Eveleigh House from 10 am until noon, once every two weeks, for Crouch to visit. Crouch contested that the children were not taken there until one minute before noon, allowing him only that much time to visit. She continued to evade the order, even after the children were to be taken to the residence of Justice-of-the-Peace Hatfield Clark, to the point she was held in contempt, at which time the matter was handed to Gen. Bradley Winslow.

With such a reputation as Crouch’s and the condition of his wife, Mary Daly and George Allen, when the local doctor, Dr. Lord, was notified and the coroner and undertaker arrived, they sent Constable Mason to where Wilbur Crouch was bedding in Sackets Harbor and arrested him.

Crouch, a butcher by trade, said, “My God, what will my poor children do?” and said he knew nothing about the murders. He admitted having known Allen for two years and was subsequently arrested and taken to Jackson’s barn, locked up with two officers watching over him. He was later removed to the old Jefferson County Jail, where he remained steadfast in his innocence.

As the inquisition ensued, much of Allen’s story was corroborated as well as Crouch’s ruthless history. Patrick Shannon, brother to Mrs. Crouch, confirmed the night of the party at his mother’s house that George Allen had told him that he believed Crouch was following him.

Meanwhile, as George Allen improved in the hospital, more of his background came to light, with theories spreading. George Allen was not who he claimed to be, his name was now believed to be George Allen Haynes, a man described as being “very susceptible to the charms of womankind and always had a number of lady friends and admirers,” according to one source. In fact, George Allen was married, and his wife residing in Chicago at the time though it was unknown if they were separated.

Furthermore, the investigation revealed some interesting information printed in the Watertown Daily Times–

Soldiers returning from Watertown saw the team make a turn into a lot of the farm of Sackets Harbor and investigators were able to match one of the horses’s distinctive hoofs to that of a track, measuring and fitting exactly. “The team evidently was driven into the barnyard and down a small incline to avoid meeting the rig full of soldiers which was coming from Watertown. The team certainly would never have left the road in this way and no one except the murderer, who desired to avoid meeting anyone, would have made such a circuit.

The team was traced coming back toward the road again and turning in the direction of Watertown. It is close to this point where the ground is still saturated with the pool of blood where it is supposed the driver stopped the team and let it take its own course into Sackets Harbor.

The inquisition provided additional information about Allen’s wounds, having been shot four times. One bullet entered behind the right ear and was extracted above the right eye. This later was acknowledged as the source of Allen’s pupils’ different sizes. Another entered under the chin and was taken out of the jawbone. Two more bullets, or something sharp, pierced the side of his neck.

Dr. Ware, attending to George Allen, said it was “perfectly absurd to assume Allen inflicted any of the wounds upon himself,” and that Allen’s mind was not year clear and that it hadn’t been since he was under the care of the staff at the Madison Barrack’s hospital.

Nevertheless, theories arose about Allen being the killer, some of which were printed as facts and fiction bled together in the form of ink in the newspapers. It was said that, during the events and subsequent trials, the Watertown Daily Times paid subscriptions increased by over 1,000. Everyone seemed to have an opinion as to a theory, and if they didn’t, they could read about them in the newspapers almost daily.

Despite the speculation of Allen’s guilt, there simply was no motive to be found, and the inquisition ruled with the following–

From the evidence produced before use we believe Mary Crouch and Mary Daly came to their deaths by guns shot wounds produced by the hand of Wilbur Crouch.

In witness whereof the said jurors aforesaid have to this inquisition set their hands this 16 days of April, 1897.

The case would now await arraignment, and one of the first things done was the exhumation of Mary Crouch’s body from the Arsenal Street Cemetery. Other details came forth, such as finding a .22 caliber revolver in the bottom of the buggy, which was used in the shootings.

On May 10th, the Watertown Daily Times published an article that summed up the many dilemmas the trail faced–

From the evidence produced before use we believe Mary Crouch and Mary Daly came to their deaths by guns shot wounds produced by the hand of Wilbur Crouch.

In witness whereof the said jurors aforesaid have to this inquisition set their hands this 16 days of April, 1897.

Over the course of the following eight days, it was realized that George Allen, believed to be George A. Haynes, was neither: his real name was Edward G. Haynes, George Haynes being the name of a brother. Despite this revelation and the cloud of mystery hovering over him, George A. Haynes had the unwavering support of his fellow soldiers and officers.

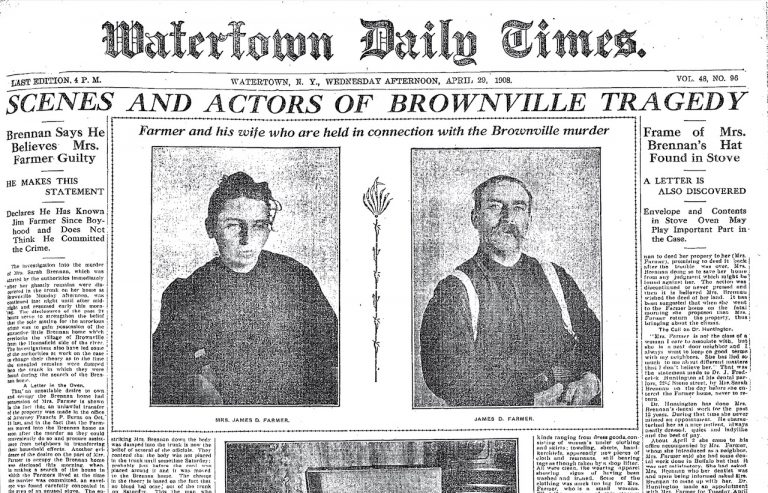

Nevertheless, on May 18th, the bold headline in The Times read, “SENSATION IN COURT, THE SOLDIER ARRAINGED.”

Yesterday marked the turning day in the Sackets Harbor double murder case. The cloud of mystery overhanging the tragedy has been lifted by the action of the grand jury and Edward G. Haynes, alias George Allen, the accusor of Wilbur Crouch, is now the accused, two indictments having found against him for murder in the first degree.

Wilbur Crouch, after 31 days of incarceration in the county jail with the terrible charge hanging over him, has been liberated, and Haynes, his accusor, now occupied the cell he vacated.

Haynes must stand trial for the murder of Mary Daly and Mrs. Wilbur Crouch, and judging from the result of the evidence adduced before the grand jury, it will be a difficult matter to save him from the electric chair.

Allen confirmed Edward G. Haynes was his name and made no reply when told he was under arrest. He did provide some other personal history, that he was born May 10, 1869, in Morris, Livingston County.

During the subsequent trial, Edward answered no when asked by the judge, “Have you any legal reason why sentence should not be pronounced on you?” It was surmised that Mary Daly was shot first, resulting in a scuffle between Mary Crouch and Edward G. Haynes in which

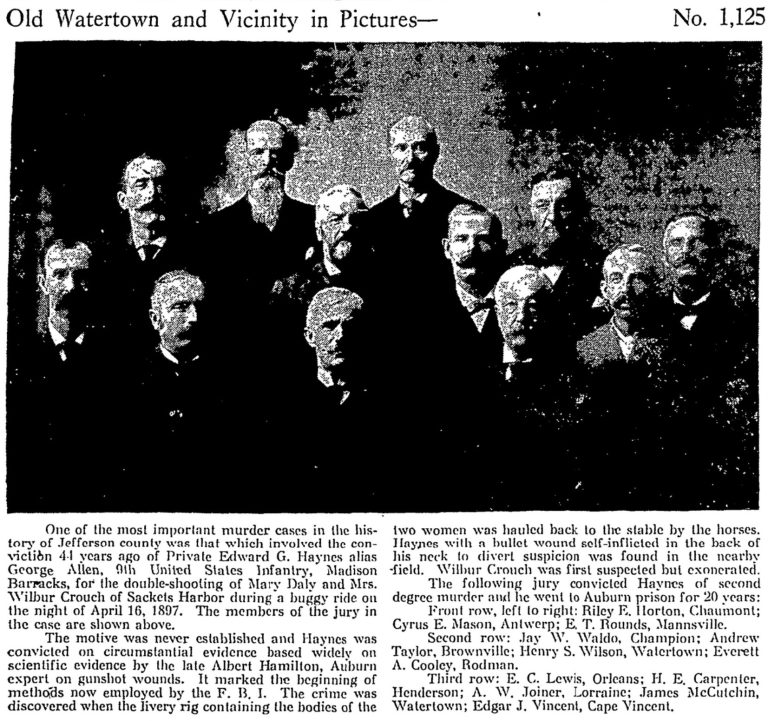

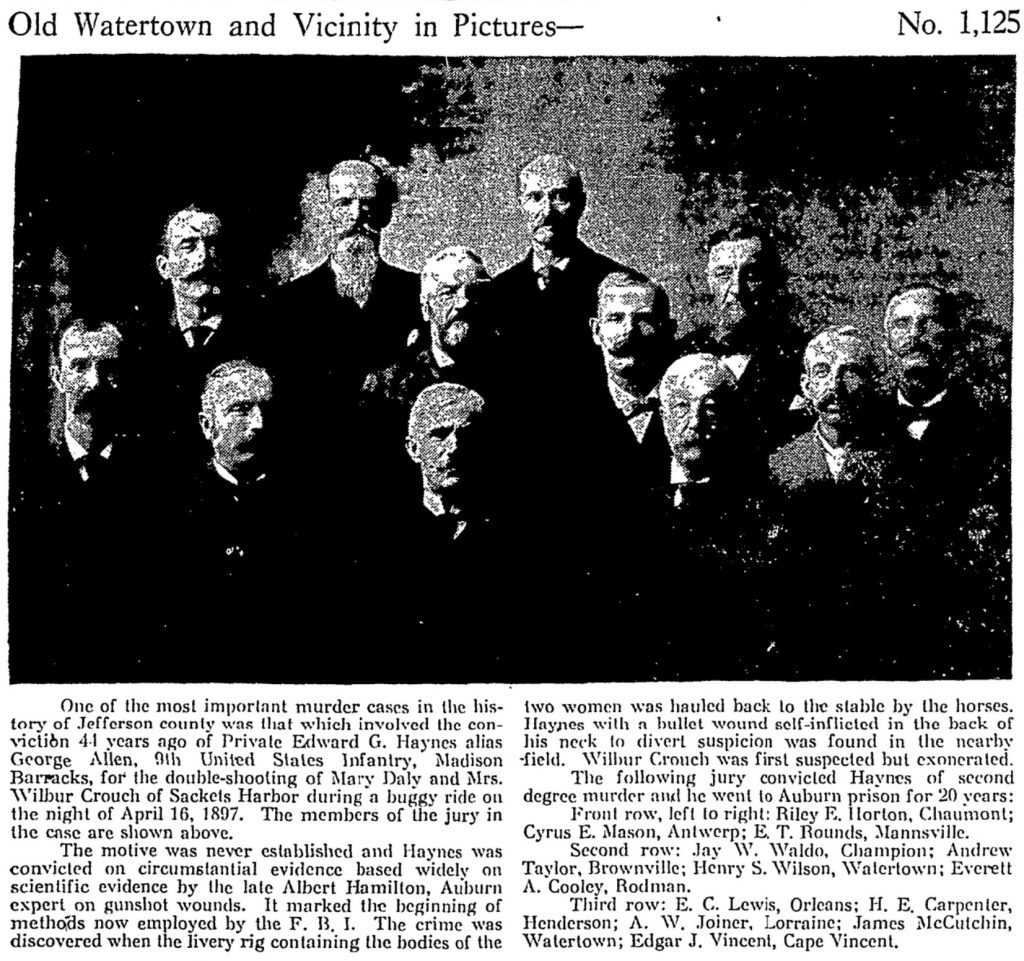

The judgment on the Crouch-Daly double murder came forth, but with all the evidence circumstantial, Edward G. Haynes avoided a trip to the electric chair with charges of 2nd-degree murder. “The sentence and judgment of the court is that you be confined in the state prison in the city of Auburn for and during the term of your natural life.”

With the sentence imposed, the fourth victim was indirectly revealed to be Wilbur Crouch, who lived for another five years before passing away in 1902. He drowned in Lake Eerie, second mate of the steamer Sylvester J. Macy of Detroit, which sank, taking the lives of its entire crew.

As for George Allen/George Haynes/Edward G. Haynes, he was reportedly a model and “excellent” prisoner and quickly earned a spot at the Auburn prison facility’s hospital. Some years later, a law passed in New York State made him eligible for parole after serving twenty years.

As the date approached, former district attorney Virgil K. Kellogg who held that role for Jefferson County during the murders, visited Edward G. Haynes in the prison and find him to be “alert, suspicious, and unwilling to make a true disclosure.” Believing him to be very dangerous and a bad man, he wrote to the state board advising against parole, stating Allen/Haynes was a dangerous character and “it is my opinion that he had been connected with other killings, and the murder for which he was convicted was a culmination of a criminal career.”

Mr. Kellogg’s pleas did not prevent the state from releasing Edward G. Haynes, who, sometime after, visited Sackets Harbor and apparently led a quiet life the remaining years he had as no further information could be obtained. However, it’s possible he assumed yet another name to escape his past.

As for the Crouch-Daly double murder, Haynes was, and remains, the only person to know what really happened that night and why. Those secrets apparently went with him to the grave, leaving the Crouch-Daly double murder, one of Jefferson County’s most hideous and mysterious crimes in the annals of its history.