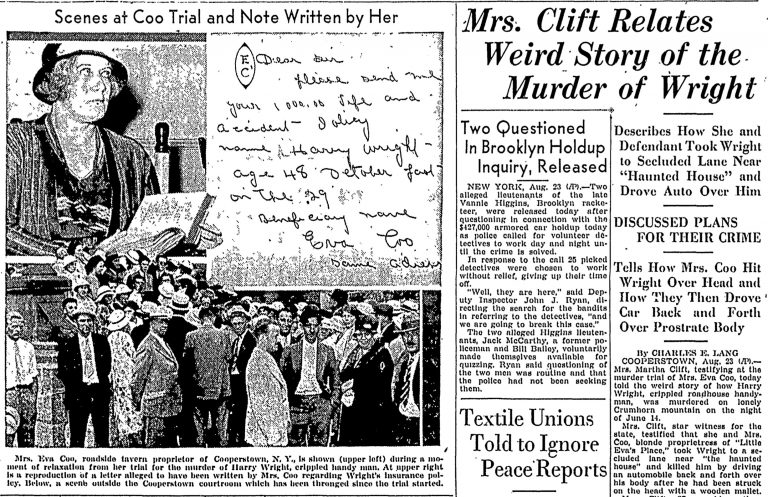

Eva Coo and the 1934 Murder at the Haunted House On Crumhorn Mountain

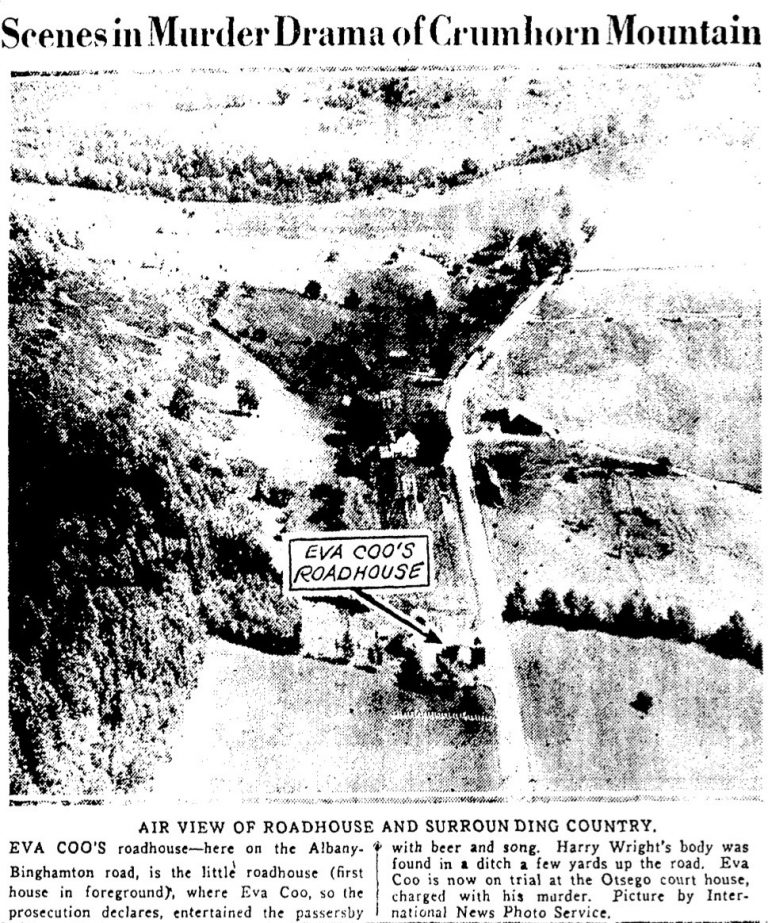

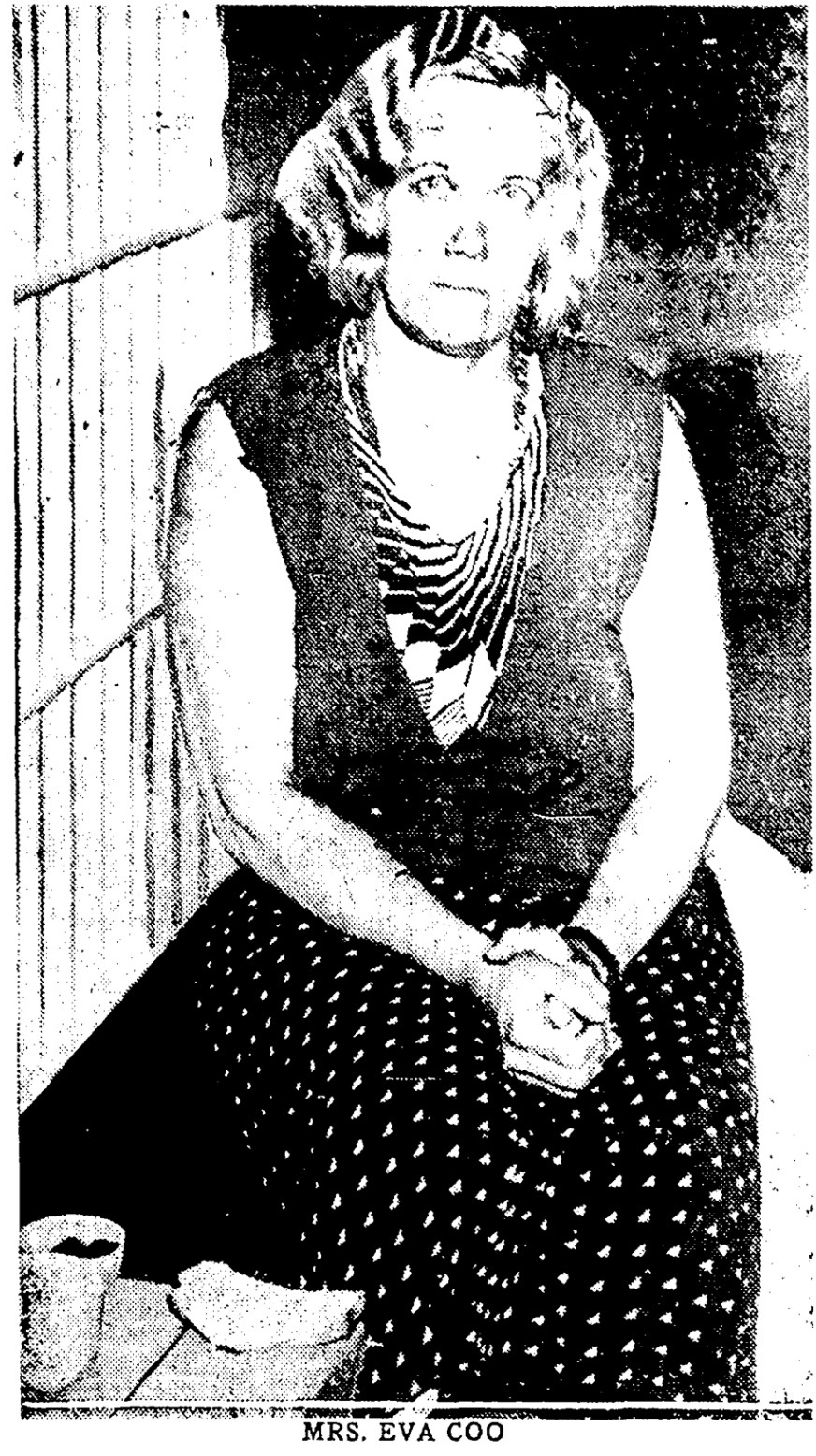

The murder of Harry Wright, 49*, by Eva Coo, 42, and Martha Clift, 25, atop Crumhorn Mountain near an old house deemed haunted by locals, was one of the more preposterous murders in the history of Central New York (technically Mohawk Valley region). The 1934 murder, located just northeast of Oneonta in Otsego County, received press throughout the state for its double indemnity, location and the ghoulish lengths the authorities took in sending Mrs. Coo to the electric chair. (*More to this later.)

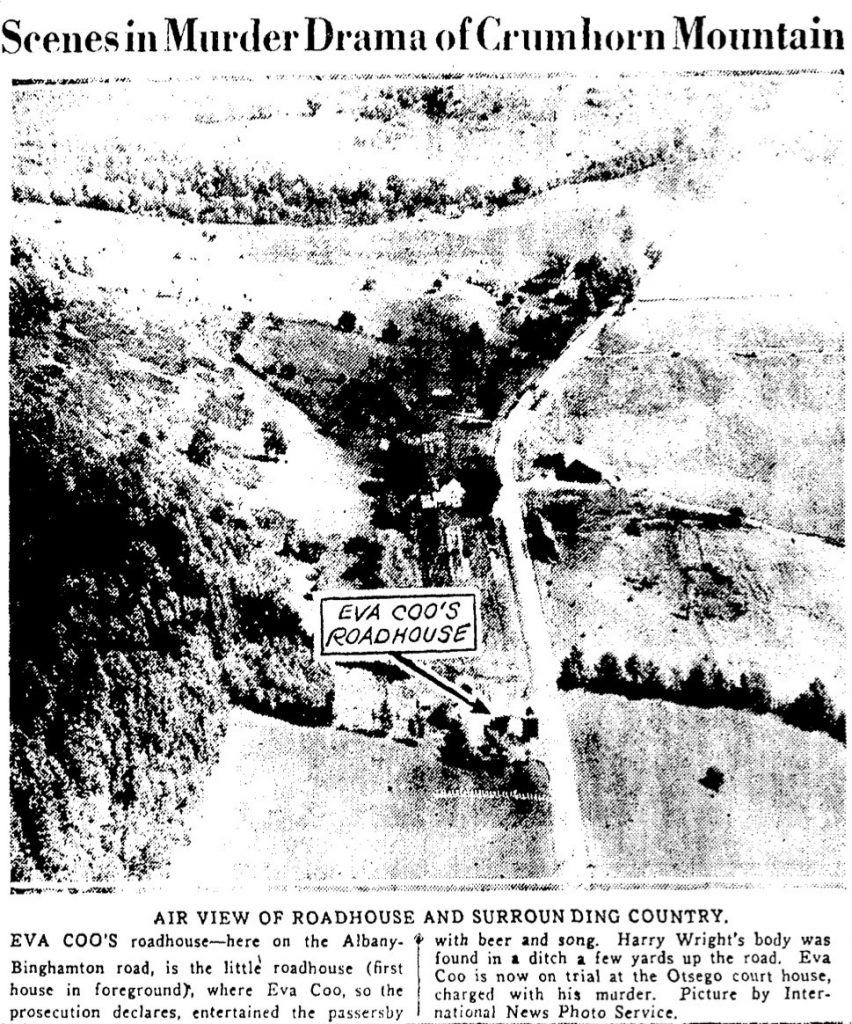

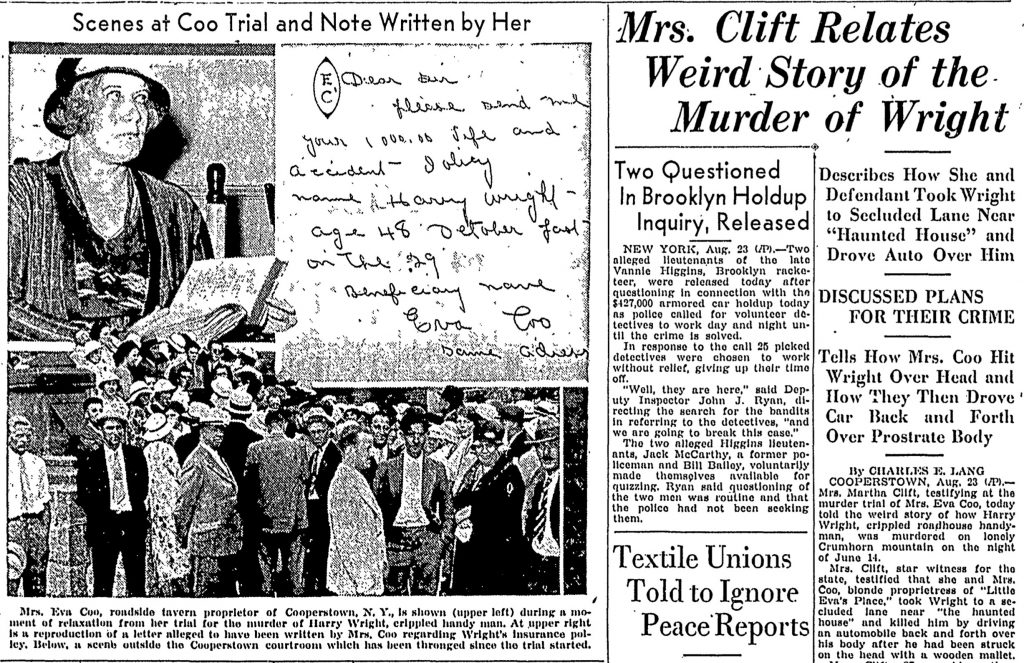

Eva Coo, a transplanted Canadian from Montreal, reported Harry Wright missing on June 14th, 1934. Wright, a handyman who did odds and ends in exchange for room and board at Coo’s roadhouse, went missing and, according to Coo, was last seen earlier that day walking into town.

On June 20, 1934, the Albany Times-Union reported—

Wright’s body was found at 11:30 o’clock Thursday night (the 14th), propped in a ditch about 100 yards from the Coo roadhouse. Mrs. Coo previously reported Wright missing to Trooper W. E. Cadwell at the Schenevus outpost.

The coroner, Dr. E. C. Winsor, initially believed Wright was the victim of a hit-run driver. He then had doubts the injuries could have been inflicted by a single blow, the entire left side of Wright’s body having been crushed and death resulted specifically from a crushed chest and hemorrhage of the lungs.

The first articles didn’t hit the press until June 20th, when it was reported four women and a man were being held on open charges involving the death of Harry Wright. Over the next day, both Eva and Martha accused each other of driving over Harry Wright repeatedly and leaving him dying on the side of a highway to make it appear he had been struck by a hit-and-run driver.

Officials said one woman, Eva Coo, was the beneficiary of three insurance policies on the victim’s life totaling $16,000 (the number would change several times throughout the coverage, but figured to be slightly over $9,800 total.)

The Watertown Daily Times reported on June 21, 1934—

Both women, District Attorney Donald H. Grant said, had signed statements charging each other with driving the car. Grant said they told him they had driven to a lonely spot on Crumhorn Mountain with Wright. Their stories disagreed on what happened then.

Mrs. Coo, the district attorney said, told him Mrs. Clift ran the car into Wright while his back was turned and then drove over him several times. Mrs. Clift said it was Mrs. Coo who ran over the cripple.

The authorities suspected nothing until several days after Wright’s body was found. Monday afternoon, the district attorney said, Mr. and Mrs. (Sarah) Benjamin Hunt reported to troopers at Cooperstown that they had seen the two women on the road near where the body was found. This, linked with other circumstances, caused them to start an investigation which finally caused them to suspect Mrs. Coo and Mrs. Clift.

Grant stated to the Albany Times-Union that Eva Coo was to be charged with murder, first degree, and the motive was to collect between $7,000 – $9,000 insurance she held on Wright’s life in small polices, some of which paid double should Wright’s death be the result of an accident.

The Times-Union further stated that Martha Clift’s statement included the three had driven to Crumhorn Mountain, where she got out of the car, followed by Wright, and proceeded to walk to a nearby field to pick shrubs. Eva Coo then proceeded to plow Wright down as he lagged behind some distance from Martha Clift, who turned just in time to see him struck and run over repeatedly. Then, according to her statement—

Mrs. Clift helped Mrs. Coo load his body into the rear of the car and drove to the place where it was found. They heaved it out the side of the car to make it appear that Wright had been hit by an automobile, she said, according to the prosecutor.

What happened next was straight out of a Hitchcock movie.

According to the Schenectady Gazette’s June 23, 1934 edition, Martha Clift admitted to the murder, having been the one who drove the vehicle, saying she was promised $200 and had worked on the plan with Eva Coo for 2-3 months. Mrs. Clift said that as she approached Wright, he turned to move out of the way, and Mrs. Coo came over and hit him in the head with a mallet.

When Wright fell to the ground, Martha Clift ran him over, and over, and over again until a moment of suspense—

Just as Wright’s body was run over, the two women saw headlights approaching. Though abandoned, the farmhouse’s owners, Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin Hunt, with Mrs. Hunt’s mother, Mrs. Iva Fink, saw the lights from the vehicle used in the murder and came to investigate.

Mrs. Clift walked down the road to meet the vehicle and talk with the owners while Mrs. Coo placed Wright’s body into the automobile. After the owners left, the two proceeded to drive back toward Coo’s Roadhouse where Mrs. Clift pushed the body of Wright out of the car after it had stopped by the side of the road.

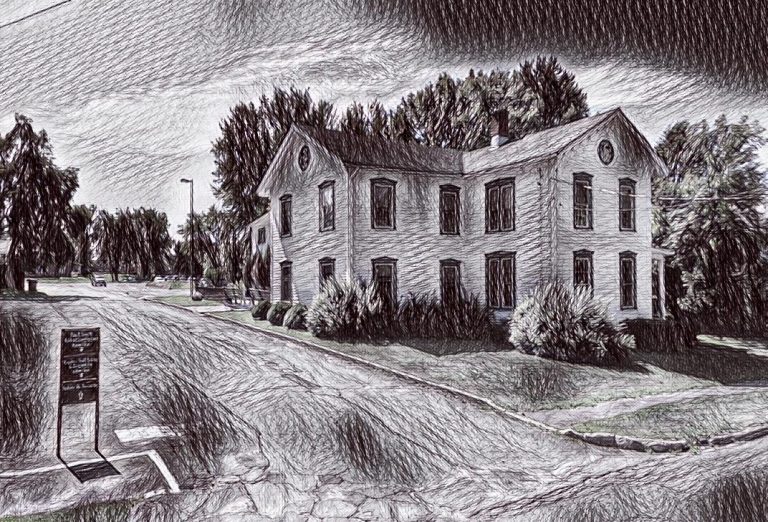

The events took a bizarre turn when Harry Wright, buried some six days at this point, had his body exhumed by authorities for approximately two hours. During that time, Eva Coo and Martha Clift were escorted to the crime scene, the unoccupied farmhouse on Crumhorn Mountain near which Wright was stricken and repeatedly run over.

The location, rumored to be haunted by locals, was five miles from where Wright’s body was discovered on the side of the Oneonta-Maryland highway where he was left to die.

During the subsequent trial, Eva Coo’s defense laid claims that the blonde roadhouse proprietor was “tortured for two days and a night” by being kept awake before signing a purported confession. Furthermore, the Watertown Daily Times reported—

Without a court order, said James Byard, Jr., chief of defense counsel, Wright’s body was exhumed six days after his death under the wheels of an automobile and taken to “the haunted house on Crumhorn Mountain” which the state has pictured as the murder spot.

There, he said, Mrs. Coo, without the knowledge of her counsel, and in the dark of night, was forced by county law officers to look on while their version of the killing was re-enacted. She was forced, he said, to lift the dead man’s body out of the road, and to shake hands with the corpse.

The purpose, he contended, was “to intimidate this defendant, Eva Coo.” She signed her statement after that experience, he told the jury.

Undersheriff Owen P. Brady, who witnessed the exhumation, stated during the defense’s cross-examination that he had met District Attorney Grant halfway up Crumhorn Mountain on the night of June 21st, that it was dark and a storm was coming as they were headed to the abandoned Scott house.

Brady confirmed the body was exhumed and witnessed its removal from the coffin and placing it where Eva Coo had said Wright was killed. However, when asked if Eva Coo held the body, Undersheriff Brady stated, “I don’t recall that she did. The body was lying on the ground and we moved it at her direction.” Brady further testified that Mrs. Coo never touched the body and that the staged recreation of the crime scene took “an hour or so.”

The state charged that Wright’s body had only $1.90 in his tattered clothing and that it was the last of the $1,800 inheritance he had been bilked of by Eva Coo. The question became, how did he become worth so much considering his age? Witnesses reported Wright was often “in an alcohol-induced fog,” easily exploited, and that his inheritance dwindled once he went to live with Mrs. Coo at her roadhouse.

Bible Provides Key Piece of Evidence

In August, District Attorney Grant introduced a key piece of evidence: a family bible. Described as “Old-fashioned calfskin binding and with well-thumbed, yellowed pages,” the bible, as the Albany Times-Union stated, proved to be a book of doom for Eva Coo. Harry Wright’s birthdate was changed to 1885 instead of his correct year, 1880. The five-year difference put Wright under age 50 when Eva Coo obtained the insurance on him using the false birthdate in the family bible as proof to insurance agents. His actual age at the time of his death was 53.

According to prosecutors, once Eva Coo bilked the majority of Wright’s $1800 inheritance, she set in motion the plan to cash in on the insurance policies she would take out on him at the expense of a “fatal accident.” When Mrs. Coo was taken into custody the night of June 19th, two troopers entered her establishment and searched her bedroom, where they found the policies in a bureau and a dresser.

Photo Called Into Question

The defense counsel for Eva Coo asked for an extended mid-day recess on August 21st so that the defense staff could revisit the “haunted house” on top of Crumhorn Mountain. Byard and his assistant, Everette Holmes, wanted to go “up on the mountain” and visit “little Eva’s place to see just what tricks the state’s photographers used in taking pictures,” according to the Watertown Daily Times.

The Schenectady Gazette reported as the trial resumed on August 21, a photo taken during the re-creation of the murder—

Earlier in the day a flashlight photograph of a man’s body lying in a shadowy lane was produced by Grant.

The picture was taken just before a thunderstorm early in the night of June 21. On this night, the defense charges Mrs. Coo was taken to the haunted house on Crumhorn Mountain and made to shake hands with the murdered Harry Wright.

“In picture No. 6 there is a man’s body,” began Defense Attorney James J. Byard, Jr., cross-examining the state’s photographer, William Warnkin.

Grant interrupted with an objection. Since the picture had not actually been introduced in evidence, it could not be made the subject of Byard’s questions, he contended.

“Well, what I want to know mostly is—did you see the body of Wright there at the time you were taking the picture?” Byard asked Warnkin, reframing his line of questioning.

“Yes,” Warnkin said.

Byard went on to contend that “trick photography” was used. The notion of “trick photography” came about when a photo showing a nearby residence “four telephone poles away from Mrs. Coo’s” represented a rise of ground where none existed.

After further cross-examination, the witness being questioned, photographer William Warnkin, responded to have taken about 60 photos that night. Byard brought out that, but one photo was taken that night and that it was amid a thunderstorm with lightning.

At this point, the defense was grasping for anything, even going so far as filing a motion for a mistrial, which was denied. The trial had become a three-ring circus with crafty entrepreneurs selling miniature mallets outside the courthouse as Eva Coo became known in the press as the “Mallet Murderer.”

Also plaguing the trial and an unlikely foreshadowing to Alfred Hitchcock’s black comedy “The Trouble With Harry,” Wright’s body was exhumed two more times, according to Daily Star.

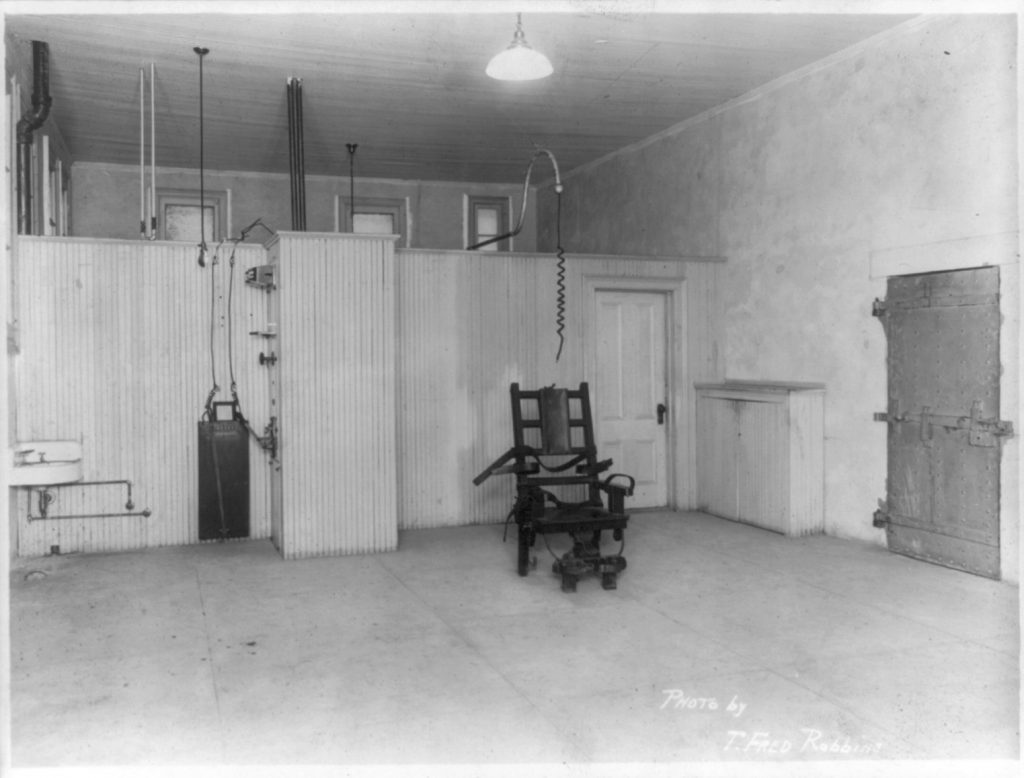

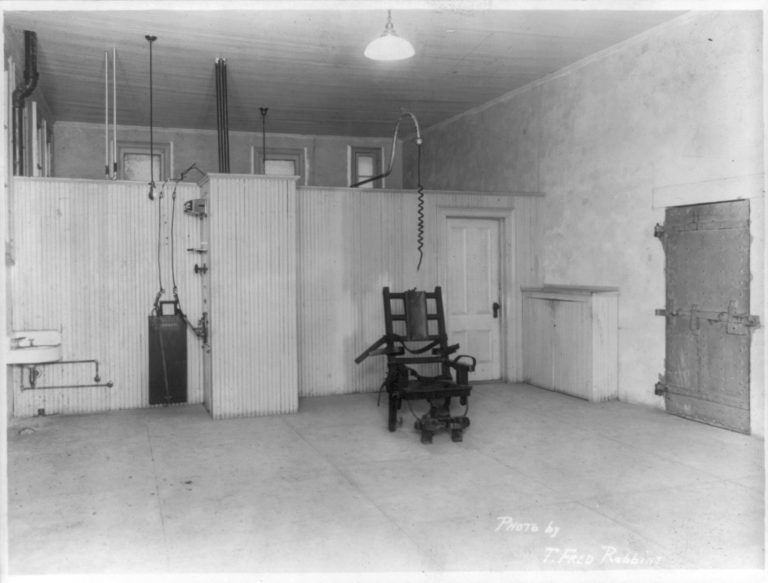

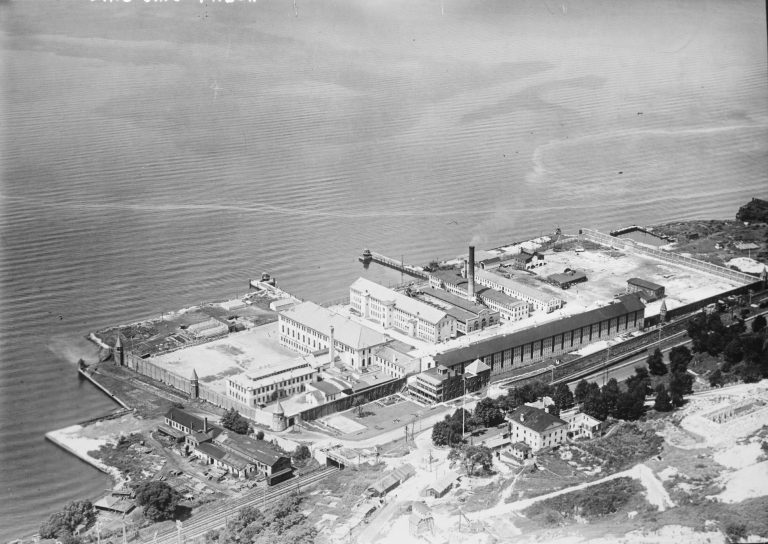

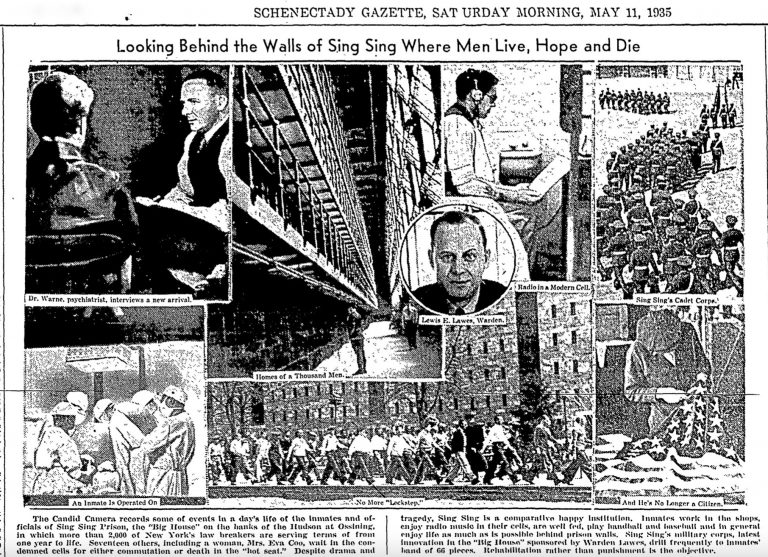

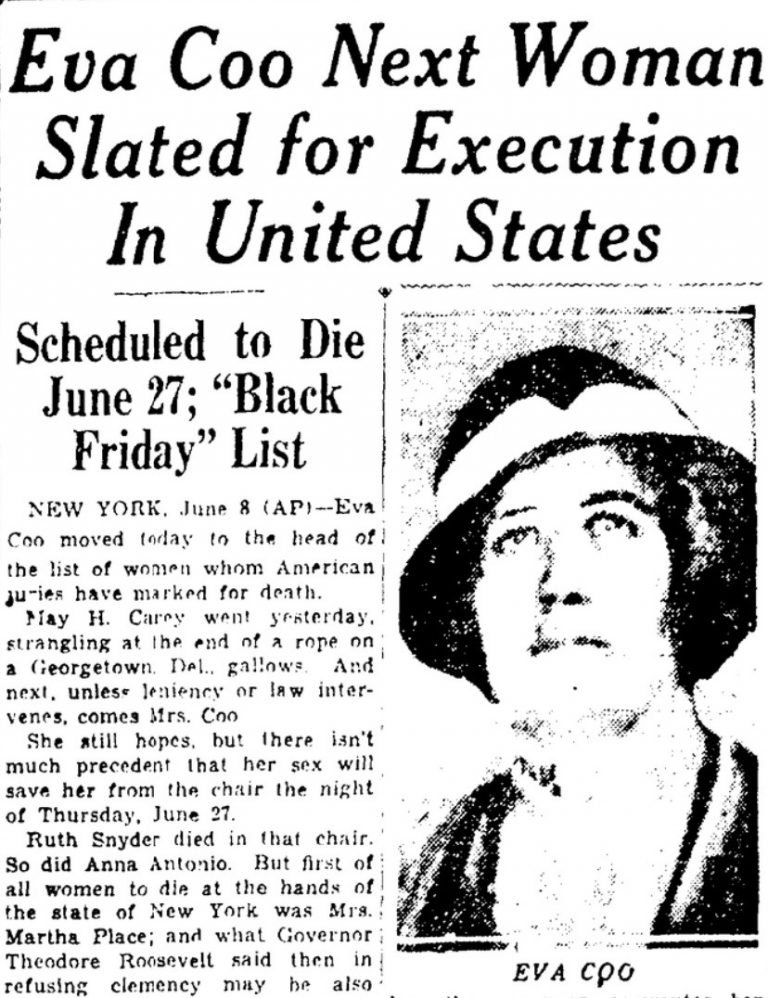

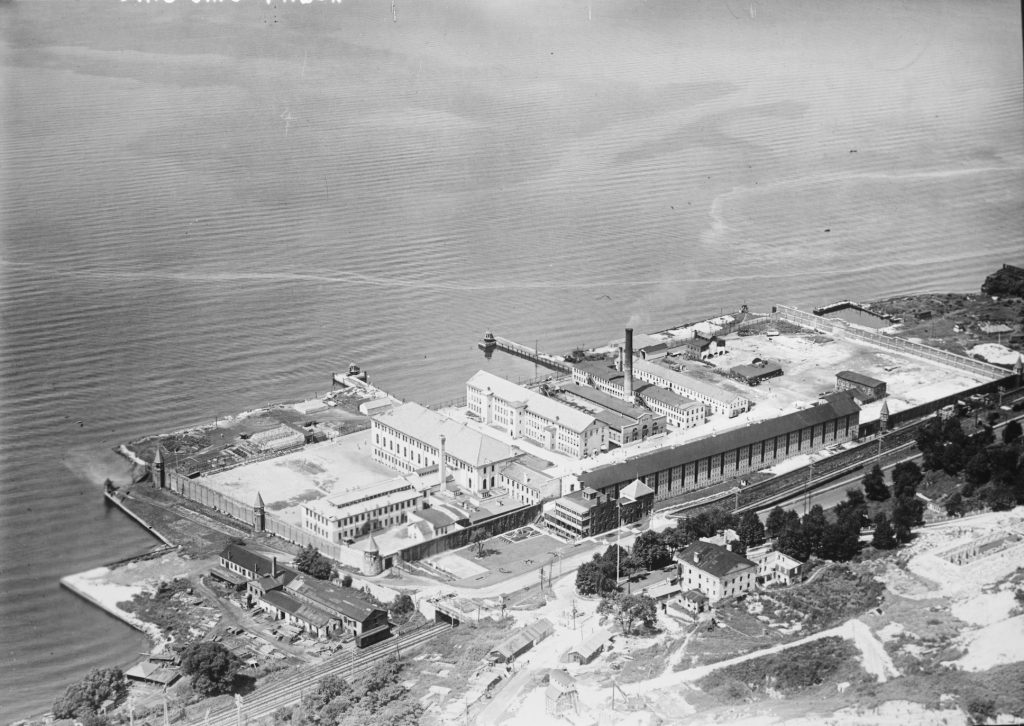

The Verdict, Old Sparky and Sing Sing

On September 6, the state took 1 hour and 40 minutes to summarize its case against Mrs. Eva Coo, demanding murder, first degree, carrying the death penalty. Justice Heath asked the jury of 9 farmers and 3 laborers to consider the facts “Fearlessly, fairly, and honestly.” The jury took only two hours for deliberation: guilty.

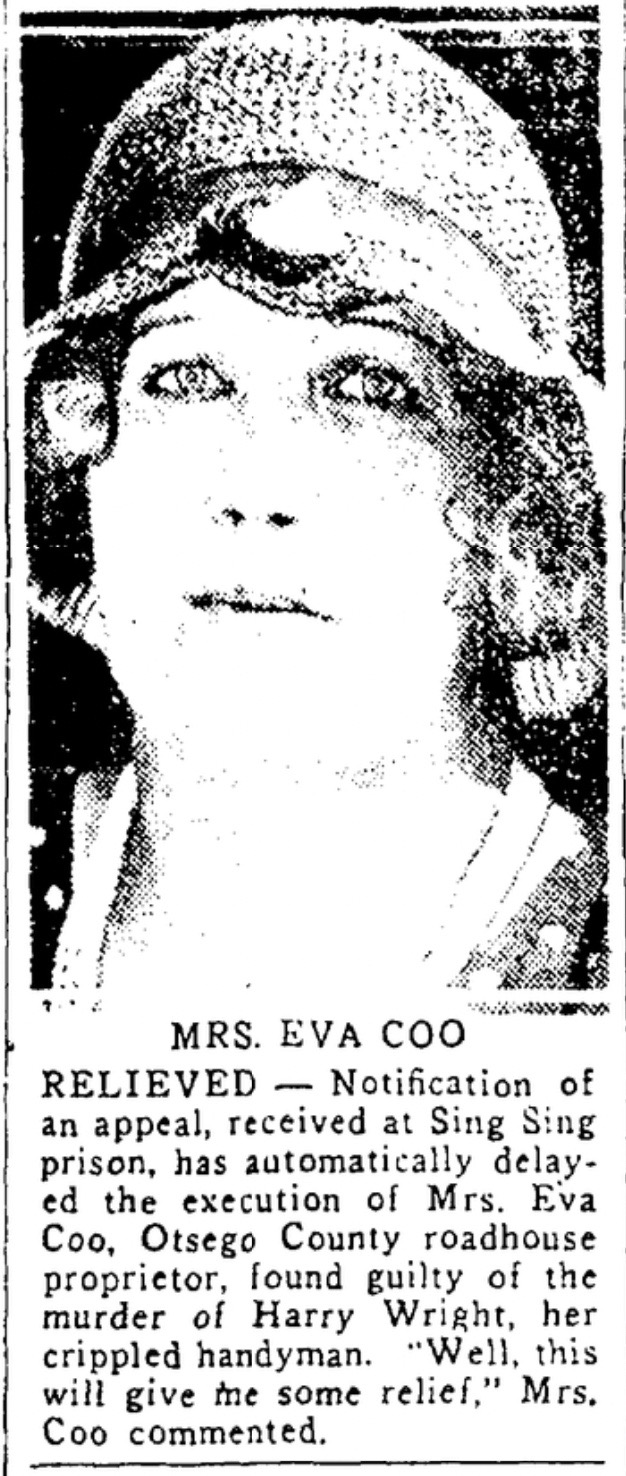

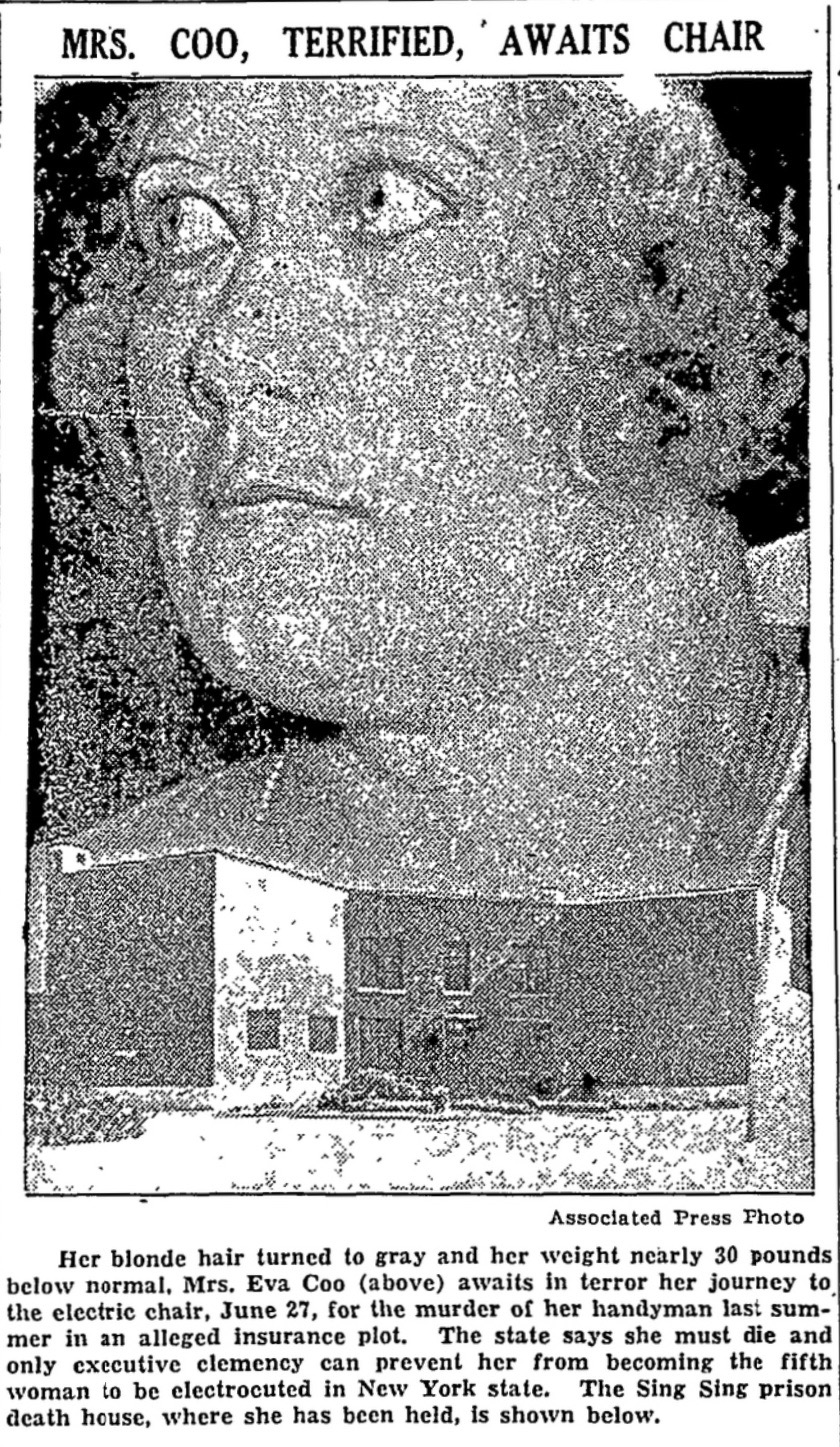

Eva Coo was to die in the electric chair, the infamous “Old Sparky” at Sing Sing, the week of October 15. Shortly afterward, Mrs. Martha Clift, who turned state’s evidence against Mrs. Coo, pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and was sentenced to serve 20 years to life in prison (she ended up serving 13 years of the sentence before being released.)

The Schenectady Gazette reported of Mrs. Coo’s reaction—

For the first time during the sensational four-weeks trial the 47-year-old (sic, she was 43) roadhouse proprietress, Canadian born, lost her composure. She shuddered violently. When she was led before Justice Riley H. Heath to hear the death sentence she walked unsteadily. Her lawyer, grey-haired James J. “Sunny Jim” Byard, gravely offered her his arm.”

Eva Coo was taken to Sing Sing the following day and given Anna Antonio’s Death Cell. Antonio was executed just weeks before Coo arrived in Sing Sing for, coincidently, murdering her husband for insurance money. Upon arriving, as was routine, the prison clerk asked, “To what do you attribute your crime?”

“I deny the commission of a crime,” was Coo’s response.

As she entered the death house, Eva Coo calmly quipped, “Well, I’m here at last.” Before leaving for Sing Sing, Coo waved Martha Clift a farewell after kissing her, saying she holds no ill-will against the woman whose testimony landed her on death row. Along with the death sentence came the appeal, which delayed the execution. This was followed by Mrs. Coo pleading for her life and an attempt to get clemency from the Governor – none of which worked.

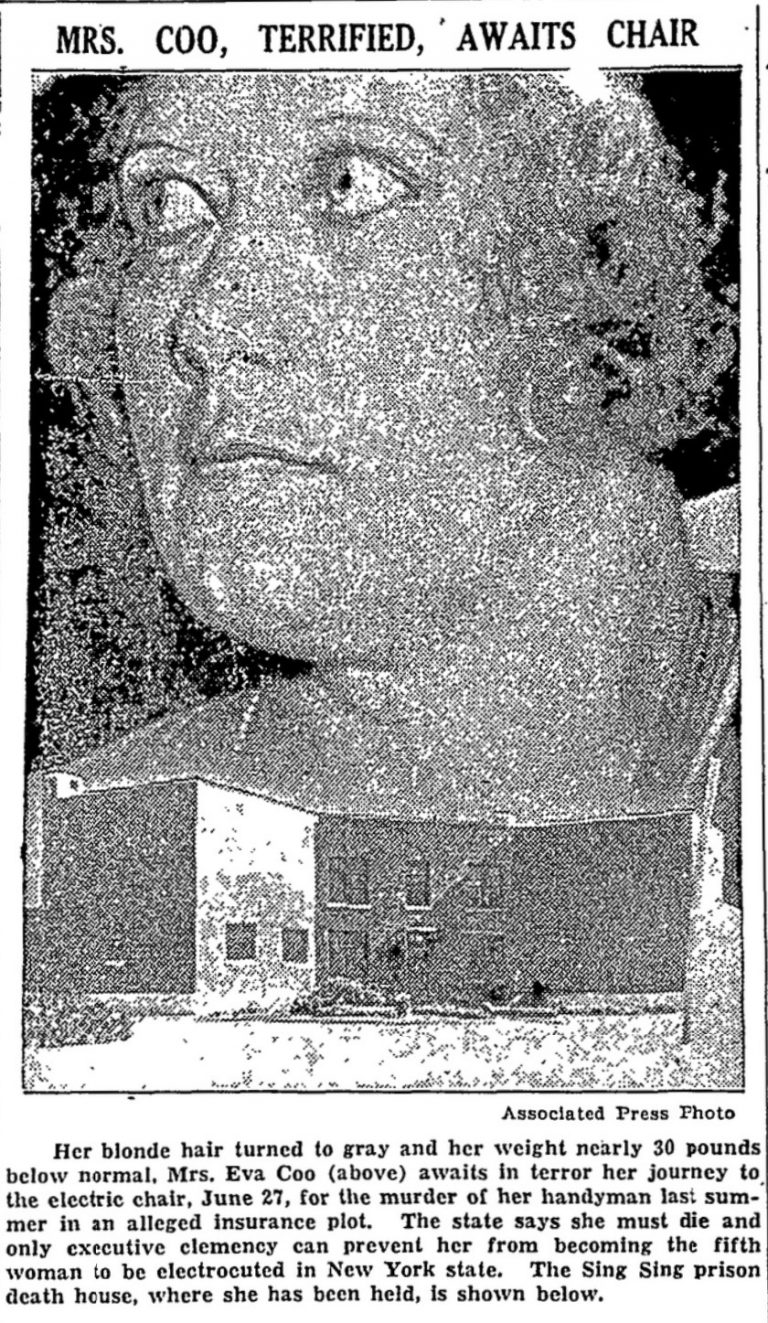

In the months leading up to her delayed execution on June 27, 1935, Eva Coo lost 30 lbs “through worrying,” according to the Albany Times-Union. At 11:03 p.m., Thursday, June 27, Mrs. Eva Coo entered the chamber to meet her fate with Old Sparky. The Schenectady Gazette reported—

She walked on into the chamber unassisted, with the Reverend Anthony N. Petersen, Protestant chaplain of the prison by her side. Her only words as she sat down in the chair were “Goodbye, darlings,” to two matrons who stood weeping.

As she sat down in the chair, Rev. Mr. Petersen read the 23rd Psalm.

“Though I walk in the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil for shout art with me,” he intoned in a low voice.

Mrs. Coo wore a blue flowered dress and brown silk stockings, the right one rolled down to facilitate the strapping on of electrodes in the chair.

She entered the chamber at 11:03 p.m. (EDT) and was pronounced dead by the prison physician at 11:07.

Her family declared Eva Coo dead years before, and her body was never claimed. Her burial occurred in a secret, unmarked, private plot in a cemetery at Adams Corners, Putnam County, near Peekskill. She was the fifth woman to die in the electric chair in New York. Martha Placed died in 1899, Mary Farmer of Paddy Hill/Brownville in 1909, Ruth Snyder in 1928, and Anna Antonio on August 9, 1934.

A book, Eva Coo, Murderess, was written by Niles Eggleston and published in 1997. In 2021, production began on an independent movie, “The Roadhouse Coupe,” about the 1934 Murder at the Haunted House On Crumhorn Mountain.

Despite its mentioning in the press, it was never explained why the abandoned old farmhouse atop Crumhorn Mountain was believed to be haunted. Though it’s presumably been long gone, no explanation would be needed if it were to exist today still.