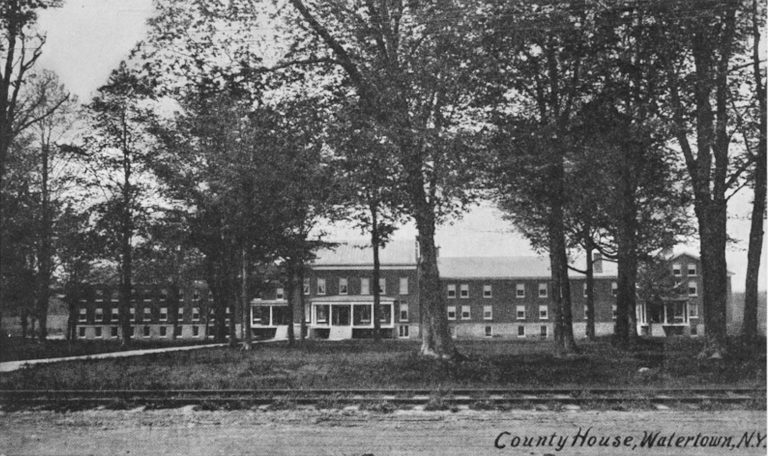

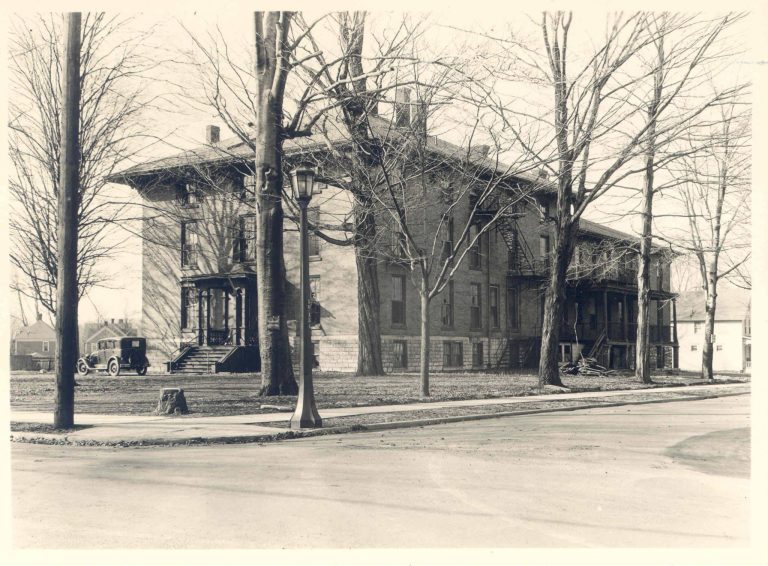

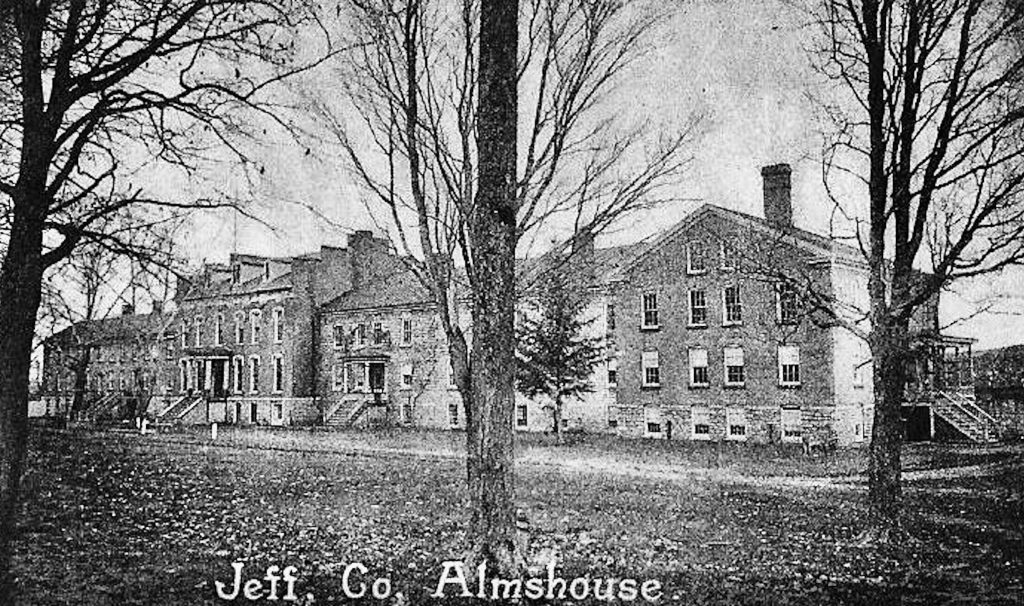

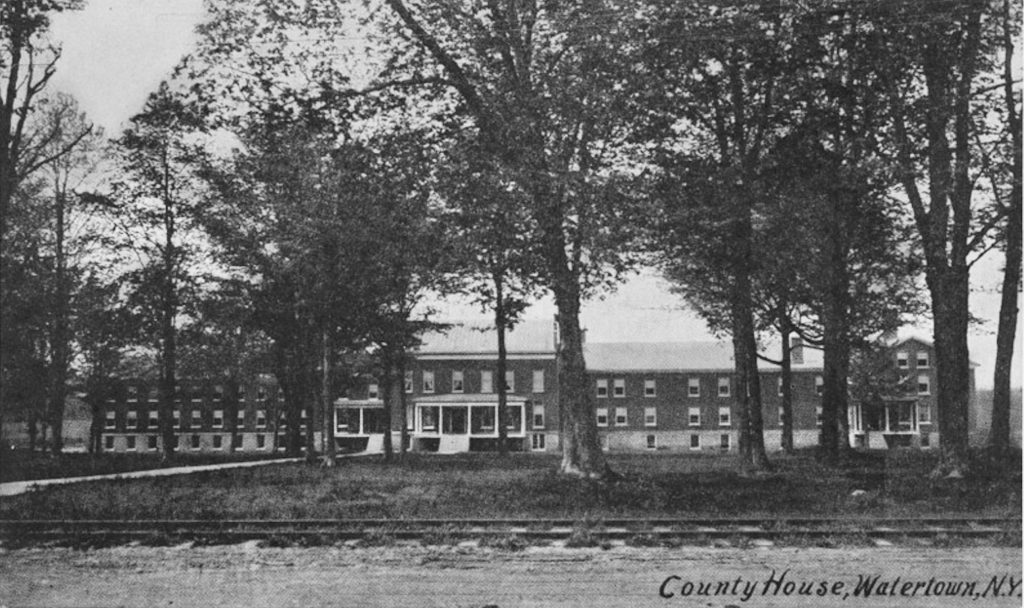

Jefferson County Almshouse, Once An Orphanage, County Home For The Aged And Deathbed Of Famed Musician Nick Goodall

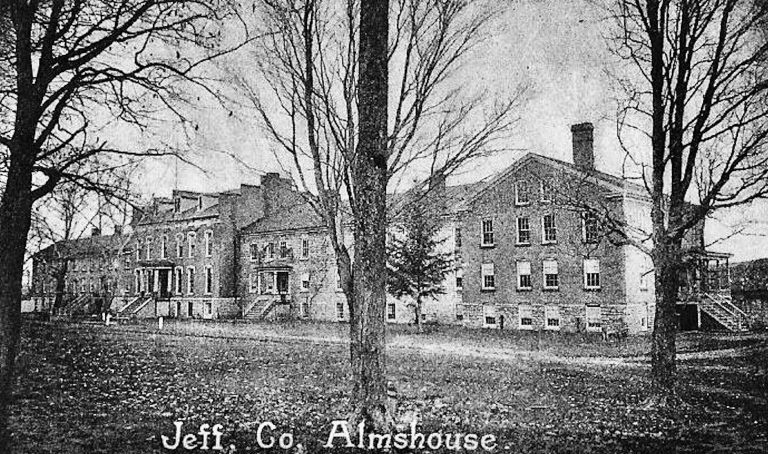

The long history of the Jefferson County Almshouse, also known as the County Home for the Aged and “Poor House,” began back in 1825 when prominent citizens were appointed to find a suitable site for erecting a poor house. A stipulation was given that it needed to be within five miles of the courthouse, then on “The Square,” located at the junction of the old County Jail on top of Coffeen Street and Court Street.

The first site chosen was the Dudley farm in LeRay, five miles from the city. It was used from 1828 until supervisors voted to find a new location in 1832. That location would be the Foster farm, described as being one mile below Watertown and north of the river—better known today as outer West Main Street.

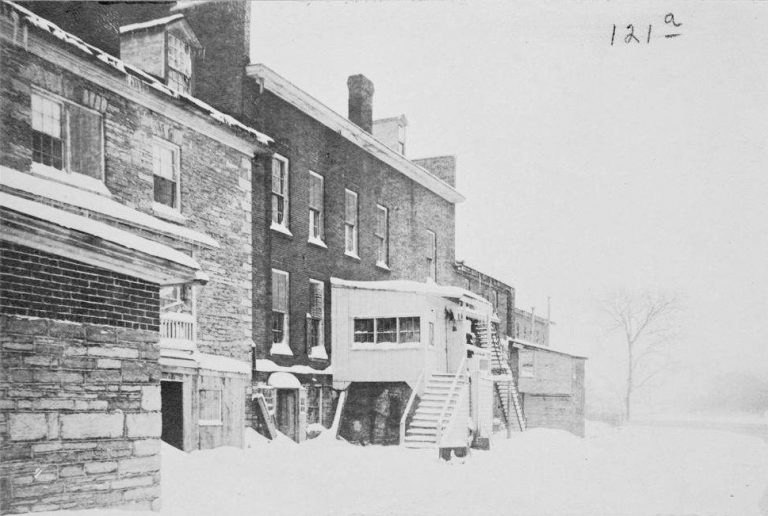

Prior to opening on March 1, 1859, on Franklin Street of what was originally named The Watertown Asylum for Orphan and Destitute Children, the facility, like most poorhouses, was intended to provide care for orphans, the elderly, the mentally ill, and individuals otherwise unable to provide, or care, for themselves. Sometimes, a fee would be charged, as at one unknown date, it was recorded: “Of the inmates, thirty-one are lunatics; thirteen males, eighteen females. Twenty-nine of these are paupers; the remaining two pay $1.50 and $2.00 per week respectively.”

In 1905, improvements would be made to the Jefferson County almshouse, including a sea wall along the river bank opposite the buildings, 450 feet long and averaging nine feet in height, to prevent the river “Water from percolating through the buildings.”

The east wing, formerly used for the insane department, underwent changes to make it into quarters for the women. Their quarters then in use were to be converted for men, with new heating and plumbing installed.

In 1908, a “Night Man in Pamelia” was a headline in the Watertown Daily Times describing an inmate, as they were referred to back then, of the Jefferson County Almshouse wandering off in which its accompanying article made reference to perhaps the almshouse’s most famous resident, Nick Goodall, to be discussed further shortly. The Times article would read–

Charles Webb, an inmate of the Jefferson County Almshouse, was found at Philadelphia this morning. He had been missing since yesterday noon. He must have done some hustling as shortly after noon yesterday he was in town of Pamelia. Several hunters were in the woods on the Nichols farm and saw the man.

He was acting after the manner of the “night man” in Eben Holden, darting from tree to tree and keeping his face hidden. He would not talk, but would mutter something about “over there,” pointing as he did so. The hunters thought he was crazy. He was in sight about half an hour, darting from tree with incredible swiftness. Finally, he disappeared completely and nothing more was seen of him. He is described at the county house as being half-witted.

A 1908 inspection found that aside from cracked, broken, and stained walls, especially in the women’s wing and basement, the building, valued at $70,000, along with the outbuildings, were in good condition and the grounds attractive. A farm valued at $7,000 also occupied the grounds. Although the water was provided by the city, it was restricted to washing as it stained the tubs, toilets, and bowls. Residents would drink and cook with well water.

In 1909, when the county was looking to build a new jail, they considered Arsenal Street and initially chose to build it “on the north bank of the Black River east of and adjacent to the Jefferson County Almshouse” at a cost not to exceed $75,000. As justification for the site cited in the Watertown Daily Times on January 9, 1909—

The site for the jail on the county house property is adequate with plenty of space for working prisoners. It will be necessary, however, to draw in stone, if prisoners are to be worked on breaking stone. A suitable jail can be constructed at this locality cheaper than within the city limits., for the reason that appearances would not need to be so carefully considered. A railroad passes within a short distance of this property, at which there is a switch where stone could be loaded and unloaded.

As history would have it, the plan was shot down and the new County Jail was built on the site of the former one. History would also see the terms “poorhouse” and “almshouse” removed from the vernacular and the Jefferson County Almshouse would become known as the Jefferson County Home for the Aged, or County Home for short.

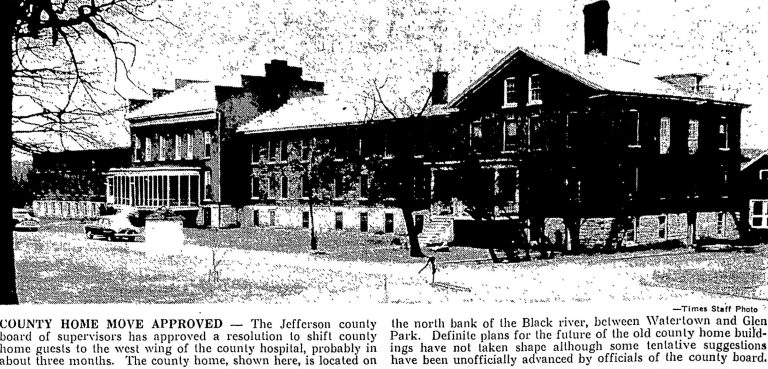

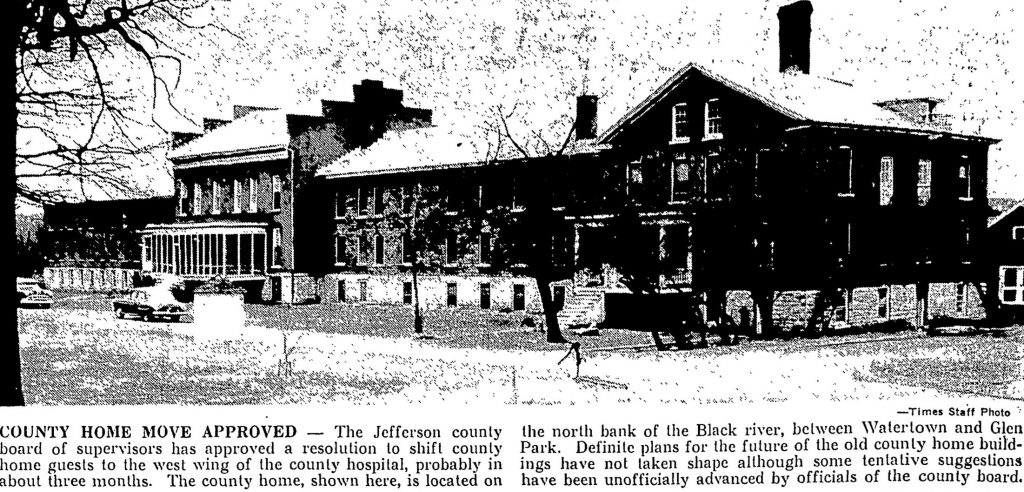

In 1963, the county home for the aged was abandoned in November. Guests (also having replaced “inmates”) were moved to the west wing of what was known as the Jefferson County hospital, aka Sanatorium, on outer Coffeen Street. The announcement made several months earlier brought about an uproar with other civic organizations, such as the North Side Improvement League, alledging elderly citizens were being used as pawns by a group of county supervisors in an effort to block the development of Jefferson Community College, which, at one point, was considering the county home for its location. Other questions remained with regard to what, if anything, the county home would be repurposed for.

One county man was so despondent over possibly moving from the West Main Street location to the county hospital on outer Coffeen Street that he apparently drowned himself in the river. J. Roblin Dulmage, the county home’s superintendent, said the man, William K. Suffel, 64, had told several others that he would “never move him” to the new location. His body was reportedly spotted by two other residents downriver, and some of his belongings were found on the riverbank behind the home.

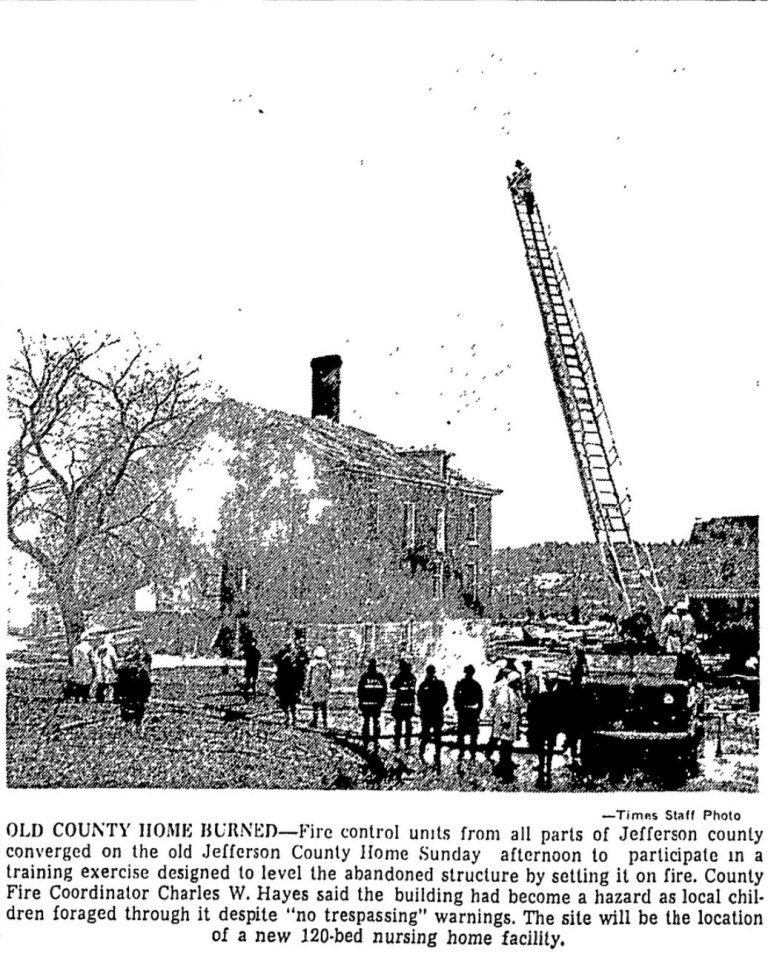

In 1965, D. H. Fellows Construction Company of Fayettville acquired the abandoned property with a high bid of $10,000. The following year, the structure was used in a controlled-fire training exercise involving units from across the county to level the abandoned property, which had become a hazard with children rummaging through it despite “no trespassing” warnings posted.

The same year, plans were in the works to build a new, $1,300,000, 120-unit nursing home facility on the site of the old county home. The plan was then changed to 80-bed and expecting approval. Still, no other word was found on the subject until January of 1970 when the North Country Library System purchased the property from D. H. Fellows Construction Company and eventually built the new North Country Library on the site.

The Story of Nick Goodall, Famous Fiddler Who Died At The Jefferson County Almshouse, 30 Years Old (or Maybe 40)

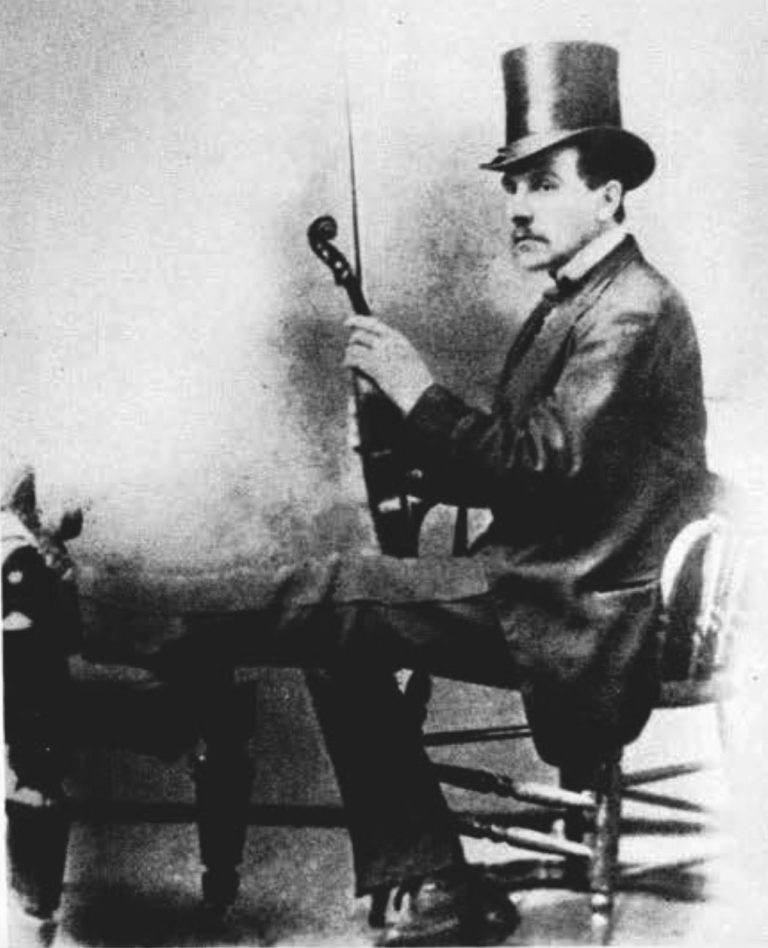

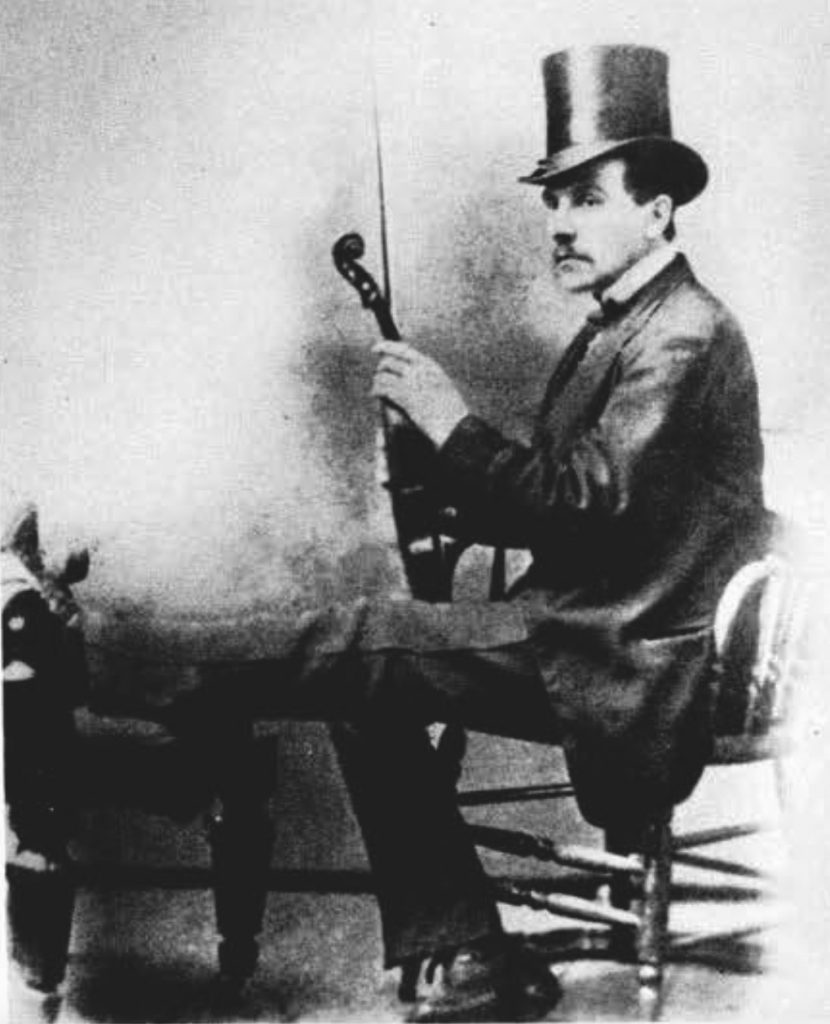

Nick Goodall, born in England, came to America at the age of nine years old. His father was considered a superior violinist but also demanded that Nick learn how to play. Fifty-plus years after his death, the Watertown Daily Times still printed articles about him, and still do to this day, but one in 1935 noted what was printed about him in Boston, Mass, where he once wandered to and from as well—

Goodall complains of cruel treatment from his father, who used to lock his son up in a room and make him play the violin from 12 to 15 hours a day, week after week. It is supposed that this treatment led to his present mental derangement.

Goodall’s father himself was reportedly the first violinist to play in the orchestra of Ford’s Theatre in Washington when Lincoln was assassinated. In 1865, Nick was “a slim, pale, silent lad” of 16 years old* who practiced six to ten hours a day and had a “great genius” for the instrument already.

*Discrepancies in his age range from 30 to 40 years of age at the time of his death.

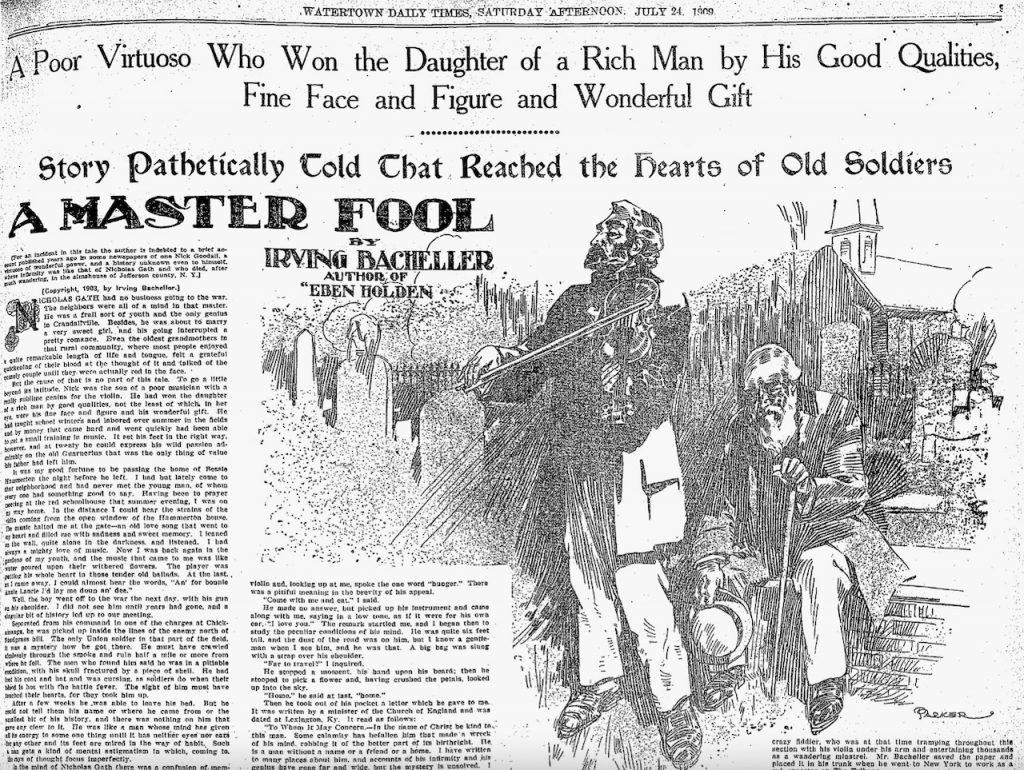

Irving Becheller would write an article that appeared in the Daily Times in 1936 that theorized Goodall’s troubles later in life were caused by bearing witness to Lincoln’s assassination as a young teenager—

Not until I was getting my color for a certain Lincoln book did I begin to realize what had happened to this sensitive young genius. No doubt he was in the theater with his father that night of April 14, 1865. Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln loved to hear the boy play and between the final acts probably he was scheduled to play for them. His father was to be his impresario, a point not to be missed.

Now we got to Ford’s Theatre on that fateful night. Everyone is laughing (during a comedy bit). Suddenly, the fatal shot, the swift, bloody struggle of Major Rathbone and the assassin, the latter’s leap to the stage, dagger in hand, the cries of murder, the indescribable panic as the head of the great, beloved man fell forward. Everyone’s heart was shaking as a dog shakes himself after a cold bath.

The unfortunate people who were a part of that terrible scene were like those overturned in a raging scene. Many were wrecked and broken by a sudden leap from laughter to appalling tragedy. The change had come with blinding swiftness. It was more than human nerves could endure. Nearly everyone in the crowd was crazy and some never quite recovered their poise.

It was that vivid account of the scene in Nicolay and Hay’s history—probably written by John Hay—that made it clear to me that Nicholas Goodall’s nervous system had been broken down in that ten minutes.

The hospitals and probably the asylums were overcrowded for a time after that, Goodall and his son Nicholas—both human beings of unusual sensitiveness—were of course nervously broken down. It is likely the father did not long survive the shock (he died two years later) and that he left his song in an asylum from which he was discharged to become inspired, penniless, and half-insane wanderer.

Nick Goodall would wander his way to Northern New York at some point, playing around the likes of Potsdam. “Nick Goodall, the remarkable violinist, still lingers in town. He has few equals with the ‘fiddle.’ He is the unfailing delight of the boys,” the Postdam Courier would say of him in January of 1879.

Later that year, after much coaxing, Nick Goodall would play at Washington Hall in Watertown. At first, he wouldn’t go on stage. Once he finally did, he didn’t leave and played all through the night. The Watertown Daily Times would say of his performance–

A very high-toned and cultivated audience assembled at Washington Hall on Saturday evening to hear the violin and piano music of the phenomenal Nick Goodall. The result was that everybody present enjoyed a very fine musical treat. Nick played a very choice program, and one that could not help suiting a variety of tastes.

Nick Goodall stayed in Watertown after that. Unfortunately, he stayed only a year and a half longer, with the better part of it spent at the Jefferson County Almshouse, where he died penniless, friendless, and destitute on January 19, 1881.

Julian Nicholas Goodall, Jr., the Crazy Musician, Dies in the Poor House

This morning at 2 o’clock, at the county asylum in this city, the eccentric and wonderful violinist known throughout the United States as Nick Goodall, breathed his last and his soul fled from this word of trouble and woe. Nick Goodall was about 35 years of age, and for the past fifteen years has wandered from place to place, earning his passage and subsistence by charming the ears of musicians with his marvelous performances upon the violin.

He was a great artist, and the mysterious, incurable idiocy that he was afflicted with, although entirely unfitting him for any professional relation with his brother musicians, had a marked effect upon his playing and it is asserted that it lent untold charms to his interpretation of the master’s works. No person can imagine the delight with which lovers of good music have sat listening to the wailings and chirpings of the professor’s instrument long after the city was wrapt in slumber, and drank in the works of Paganini, Bach, Chopin, DeBerriot, and the greatest operas that were always at the fingers-end this queer being.

The funeral will be held tomorrow at 4 o’clock at the county house, and 4:30 at the city vault back of Trinity Church, on Court Street. A sufficient amount has been subscribed for a proper burial, Rev. Danker will officiate, and the band men, musicians and others are expected to be present.

Though buried in an “obscure and forgotten” grave with a $40.00 headstone, his remains would be relocated to a more prominent place in the cemetery in October of 1903.

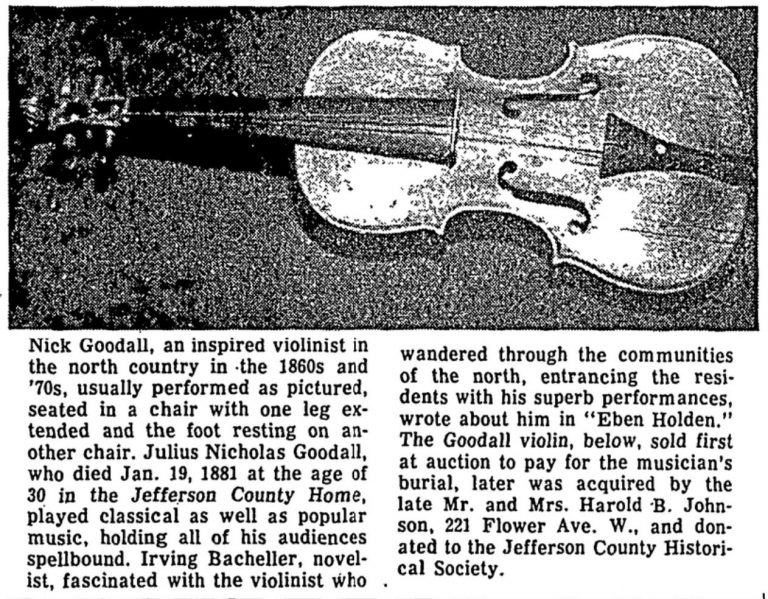

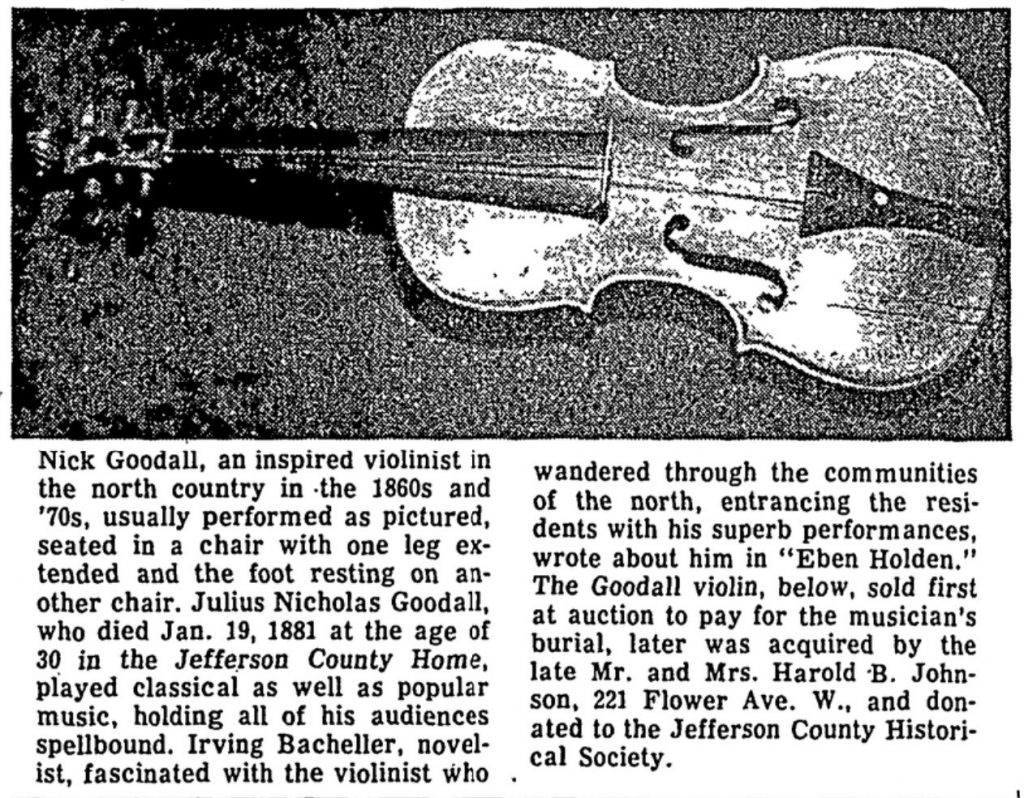

The violin that Nick had at the time of his death would be sold by raffle. A. M. Tucker of Evans Mills won and it was later sold to a man in Watertown and found its way to a local pawn shop. There, a resident of Canton came upon it and purchased it and was said to prize it highly. Written on the inside of the violin is an inscription: “Joseph Guarnerius Fecit Cremonae Anno 1719, L H S.” The violin was acquired by Mr. and Mrs. Harold B. Johnson and donated to the Jefferson County Historical Society.

The legend of Nick Goodall would live on long after his death, immortalized as a famous character in author Irving Becheller’s well-known book, Eben Holden, a Tale of the North Country. Becheller would visit Goodall’s grave at the Arsenal Street cemetery when he came to Watertown High School in 1916 to give a reading at the school’s auditorium.