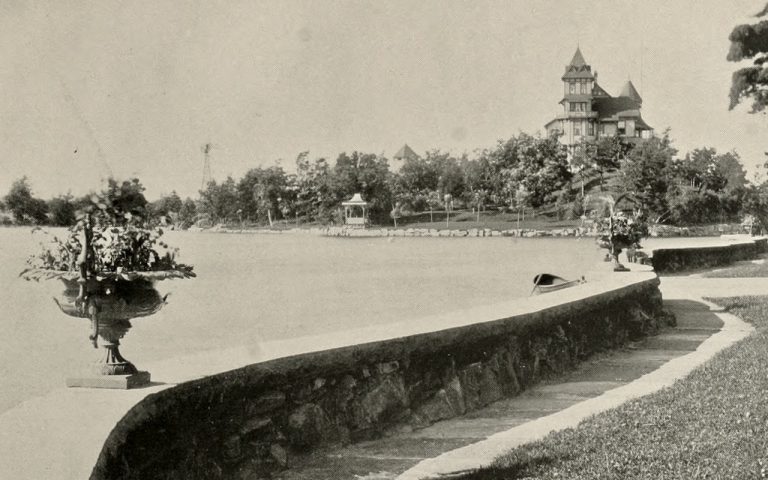

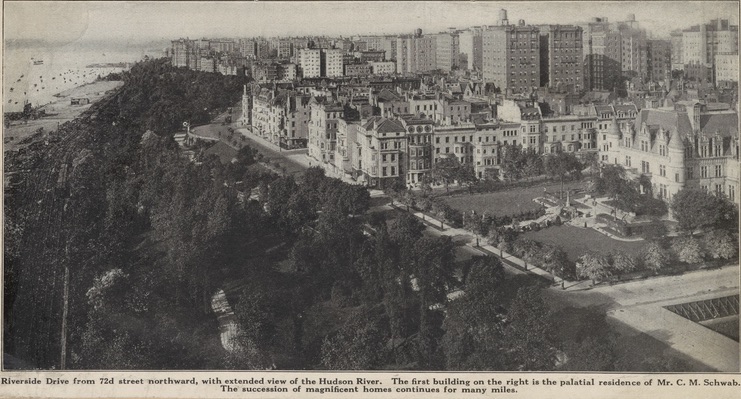

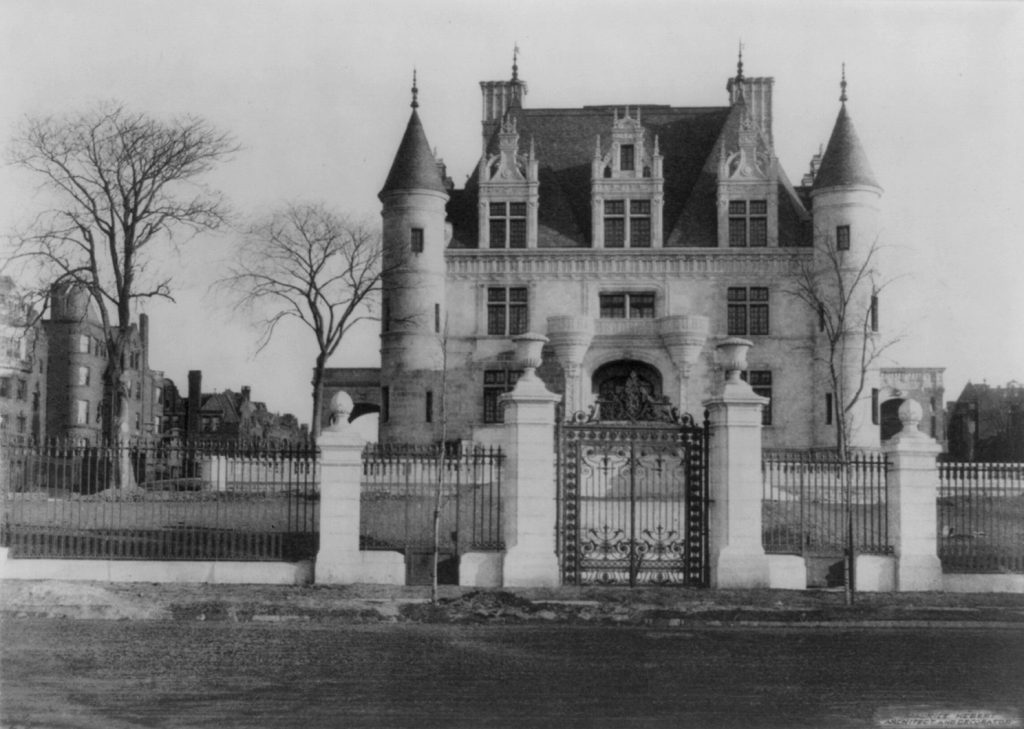

Charles M. Schwab Mansion, “Riverside,” Upper West Side of Manhattan

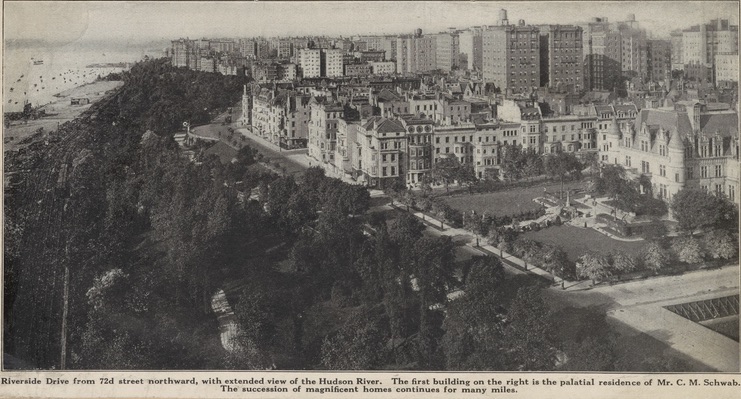

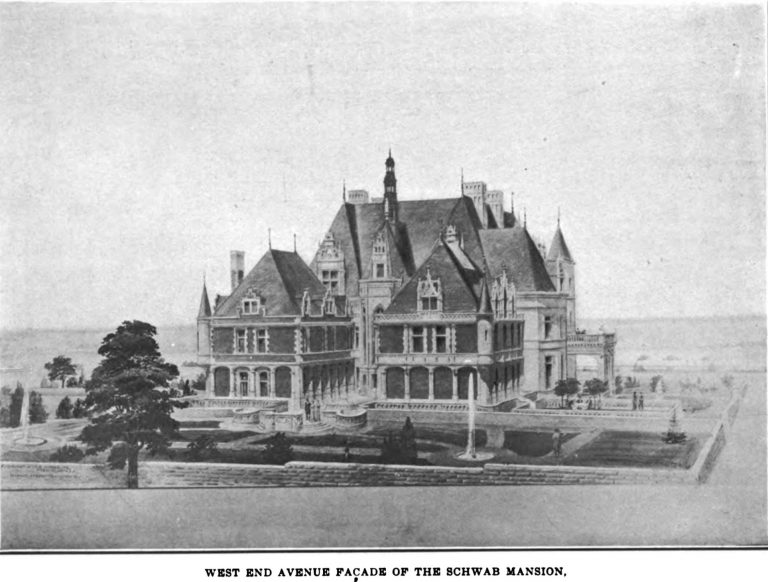

Taking four years to complete, the Charles M. Schwab mansion on Riverside, known to some simply as “Riverside,” is a prime example of some of the excesses of the Gilded Age. Designed by Maurice Hébert, the 75-room mansion was located between 73rd and 74th streets, partially on land where the New York Orphan Asylum was located, and would make Schwab’s former home in Braddock, Pennsylvania, look like a small bungalow or country cottage in comparison.

Prior to the start of its construction, the Schwab mansion’s design was molded in wax at the cost of $20,000 with an expected price tag of $2,500,000 and anticipated to be completed by Christmas, 1904. At the time, the Watertown Daily Times noted the Schwab mansion’s costs to be “a pretty fair price for a man to pay who a few years ago was working with his hands for a living.”

Indeed, Schwab had earlier started out as a laborer working for Andrew Carnegie’s Edgar Thompson Steel Works. He would work his way up the ladder over the years, becoming an assistant manager and then manager by the late 1880s. After a strike plagued the Homestead plant Carnegie had acquired, Schwab was asked to mend relationships between management and workers. Not only did Schwab succeed in that, he also bolstered the plants efficiency which aided Carnegie’s rise in the industry. By 1897, Schwab had ascended to president of the Carnegie Steel Company.

A few years later, Schwab would become the first president of U.S. Steel which was formed by J. P. Morgan in 1901. The opportunity arose about a year and a half after the death of former New York State Governor Roswell P. Flower, who had become the “Wizard of Wall Street,” disrupted plans by Flower and W. H. Moore (of the National Steel Company) amongst other investors to purchase the holdings of Andrew Carnegie.

Charles Schwab would suggest the merger to J. P. Morgan and, after completion, would serve as president for two years, but ultimately resign due to conflicts. He would then set out to head the smaller Bethlehem Steel which he still had a controlling interest, turning it into one of the most powerful steel-manufacturers in the world.

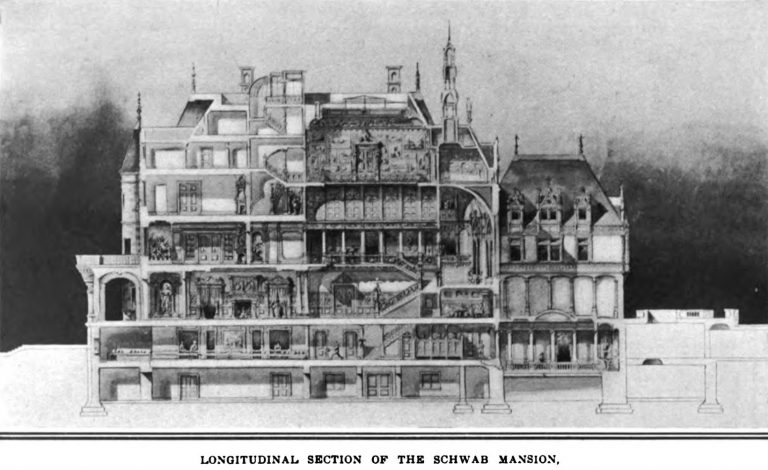

During his rise, Charles Schwab would set out to erect the Schwab mansion in New York City’s Riverside district. The mansion and its premises would take up the entirety of a city block and become quite a spectacle in the process, but not without criticism. Final estimates, depending on the source, vary from $5,000,000 to $10,000,000. Using $6,500,000 as figure in between represents, in 2021 dollars, an investment of over $195,000,000. The Schwab mansion was said to have had 6 elevators (some sources say 3) and required 10 tons of coal to heat a day, per Pittsburgh Quarterly‘s wonderful article Smilin’ Charlie Schwab, by William S. Dietrich, II and various newspapers.

Nearing its completion in October of 1905, Architect and Engineer included a small piece in its Vol. 2, Issue 3 edition that could be interpreted in a variety of ways. Whether scathing, sarcastic or humorous, the writer(s) evidently were not impressed and made their thoughts known. The article in its entirety is referenced below–

Charles M. Schwab has built a mansion on Riverside Drive, New York City, at a cost of about eight million dollars, says the Decorative Furnisher. Mr. Schwab is a typical prosperous American iron magnate. He made his money in and near Pittsburg, in the iron business. In iron he is one of the most talented men in the world. In other things he is nothing remarkable. His eight million dollar house is less remarkable than Mr. Schwab himself. It is an eight million dollar example of period styles. This house will be talked about all over the United States. It will be illustrated in all the ladies’ magazines, and the newspaper Sunday supplements will glow about it.

Do not forget that the house cost eight million dollars. Whenever you look at one of the pictures of its like-France interiors remember that eight million dollars was the cost. The house is interesting—because it cost eight million dollars. It is not especially interesting for any other reason except as showing that even eight million dollars is not sufficient money to induce an American to create a truly American house.

Mr. Schwab has obtained, doubtless, his full eight million dollars’ worth. He has paid for a house that is as unlike Mr. Schwab, the Pittsburg iron man, as anything could well be. The pictures of this house are like wood cuts and engravings of the elegant palaces of France. The house itself is a masterpiece—it is an eight million dollar masterpiece—but it is a French mansion dollars and forty years of time.

We do not doubt in the least that Mr. Schwab got just the kind of a house he wanted. We doubt if he could have secured an original and high-grade American house for any mere eight million dollars. To reproduce or to adopt a period style to give absolutely perfect results eights million dollars seems quite sufficient. To get an American to createa house that would show absolute originality would probably cost Mr. Schwab eighty million dollars and forty years of time.

The architect, to say nothing of the decorator and finisher, would probably have to be born, bred and trained for this particular job What he would do after this structure was completed we do not know. Probably he would be transported.

During his rise, Schwab had a number of transgressions that would ultimately come back to haunt him. While married, he had an affair which resulted in the birth of an illegitimate daughter, his only child, which he would spend lavishly on. In today’s culture, Schwab would be referred to as “politically incorrect,” with the telling of off-colored jokes that made him an easy target in the press. His biggest vice was gambling, something he tried mightily to hide from Carnegie. Once the press picked up on a trip to Monte Carlo in 1902, Schwab would be at odds with the company and resign in 1903.

Schwab would get back to the smaller business and growth-potential he clamored for rather than being saddled with investors, boards and the like that hindered many of his plans. He would return to Pennsylvania and purchase Bethlehem Steel outright and shape it into the second largest steel corporation in the United States by the time of his death, mostly due in part to the hiring of Eugene Grace as CEO who more or less played the equivalent to Schwab’s relationship with Carnegie.

Schwab, however, wasn’t as fortunate. With his lavish spending, tastes and bad investments (really, was not Schwab mansion a type of investment?), he would slide the slippery-slope downward through the depression and, despite a token Chairman position with Bethlehem Steel and a $250,000 annum, would die virtually penniless and bankrupt in 1939.

As for the Schwab mansion, before his death in 1939, Schwab had offered its use to the city of New York hoping it would become a mayoral house. Mayor LaGuardia would turn down the offer, finding the Schwab mansion gaudy – a move that portended its fate, that is if the diminishing number of mansions and ever-creeping closer high-rise buildings hadn’t already signaled its days being numbered.

On April 11 1945, the Watertown Daily Times would report via the Associated Press–

Schwab’s House Is For Rent, $75,000 Per Year

‘For Rent’ signs appeared, figuratively, on the J. P. Morgan and William Guggenheim suburban mansions today, shortly after the Charles M. Schwab town house and William K. Vanderbilt country home were registered similarly with the city’s vacancy listing bureau.

Both the $1,500,000 Morgan house–46 bedrooms, 21 baths, two kitchens–and the relatively cottage-like Guggenheim mansion–20 rooms assessed at $380,000–were offered primarily for foreign government missions.

The 750-room, $3,000,000 Schwab mansion on Riverside Drive has been offered for $75,000 annual rental.

A spokesman for the Chase National bank, custodian of the Schwab showplace, did little to entice potential tenants.

“There is not a piece of furniture in it,” he said. “It takes about 10 tons of coal per day to heat it in the winter and it could be made suitable for accommodating a number of families only at a great expense.”

A fire-sale would be held in 1947, essentially readying the property for demolition. Lights, chandeliers, wall paneling… anything that could be hauled away, was. To demonstrate the discrepancies in pricing the Schwab mansion, amongst other figures, the above article from 1945 mentioned $3,000,000, whereas the October 17th article in 1947 announcing its demolition noted in its headline, “$10,000,000 property will make way for Prudential Housing Project,” noting it to be a 40-room mansion rather than 85. Truth be told, people probably lost count on either front. Per the article–

The mansion had been untenanted since the deaths of Mr. and Mrs. Schwab in 1938. The richly ornamented estate had been up for rental at $75,000 a year, but without any takers.

Schwab had equipped the house with a pair of bowling alleys, and a $100,000 pipe organ in addition to such priceless works of arts as chandeliers, stained glass windows, mantles, and exquisite wood panelings.

Today, the 19-story 636 unit Schwab House occupies the site of the former Schwab mansion. Completed in 1950, it was converted from rental to co-opt in 1984.

A short video of the Schwab mansion meeting the wrecking ball, from British Pathé on Youtube.